Holotopia

Contents

- 1 HOLOTOPIA

- 1.1 An Actionable Strategy

- 1.2 Imagine...

- 1.3 A proposal

- 1.4 A vision

- 1.5 five insights

- 1.6 A mission

- 1.7 A strategy

- 1.8 Tactical assets

- 1.9 A space

- 1.10 Five insights

- 1.11 The elephant

- 1.12 Stories

- 1.13 The mirror

- 1.14 The dialog

- 1.15 Ten themes

- 1.16 Keywords

- 1.17 Books and publishing

- 1.18 Prototypes

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

A proposal

The core of our proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would our handling of information be like, if we treated it as we treat other human-made things—if we took advantage of our best knowledge and technology, and adapted it to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of the handling of information we are proposing—by which initial answers to relevant questions are given, and in part implemented in practice.

We call the proposed approach to information knowledge federation when we want to point to the activity that distinguishes it from the common practices. We federate knowledge when we make what we "know" information-based; when we examine, select and combine all potentially relevant resources. When also the way in which we handle knowledge is federated.

The purpose of knowledge federation is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

Like architecture and design, knowledge federation is both an organized set of activities, and an academic field that develops them.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field and real-life praxis (informed practice).

We refer to our proposal as holoscope when we want to emphasize the difference it can make.

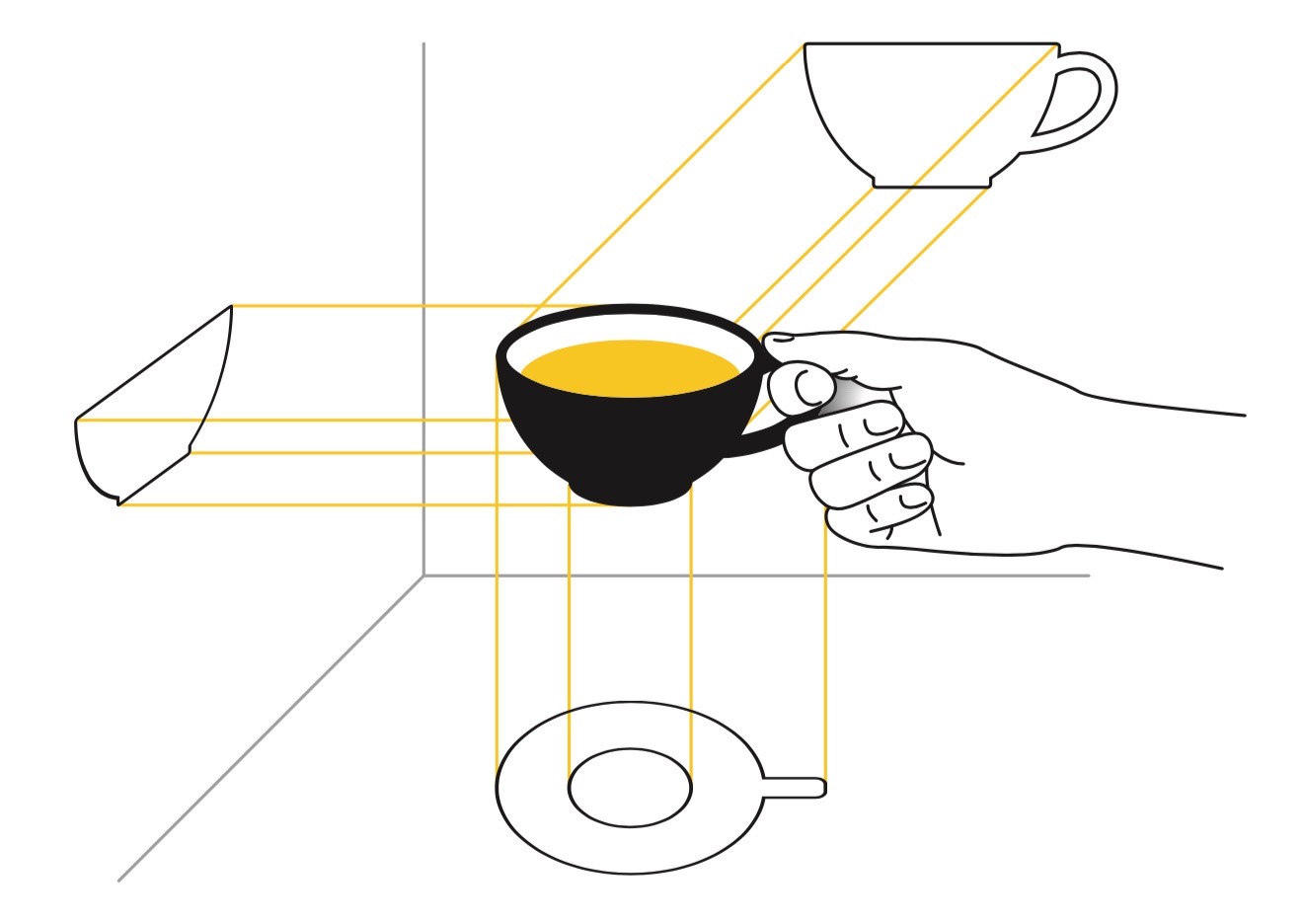

The purpose of the holoscope is to enable us to see things whole.

We use the Holoscope ideogram to point to this purpose; and to explain how this purpose is achieved through knowledge federation. The ideogram draws on the metaphor of inspecting a hand-held cup, in order to see whether it is broken or whole. We inspect a cup by choosing the way we look; and by looking at all sides. And this looking at all sides—that is what knowledge federation is about.

While the characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

In the holoscope, the legitimacy and the peaceful coexistence of multiple ways of looking at a theme is axiomatic.

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for multiple ways to look at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. The scopes and the resulting views have a similar meaning as projections do in technical drawing.

This modernization of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed creation of the ways in which we look at a theme or issue—has become necessary in our situation, suggests the Modernity ideogram. But it also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not "reality pictures", contending for that status with one other and with our conventional ones.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

A way of looking or scope—which reveals a structural problem, and helps us reach a correct assessment of an object of study or situation—is a new kind of result that is made possible by (the general-purpose science that is modeled by) the holoscope.

We will continue to use the conventional way of speaking and say that something is as stated, that X is Y—although it would be more accurate to say that X can or needs to be perceived (also) as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way (to use the offered scope); and to do that collectively and collaboratively, in a dialog.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a 'cardboard model of a city', and a 'construction site'. By sharing them we are not making a case for a specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as academic field, and real-life praxis.

A vision

Suppose we used the holoscope as 'headlights'; what difference would that make?

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in provided us a benchmark challenge for putting our proposal to a test.

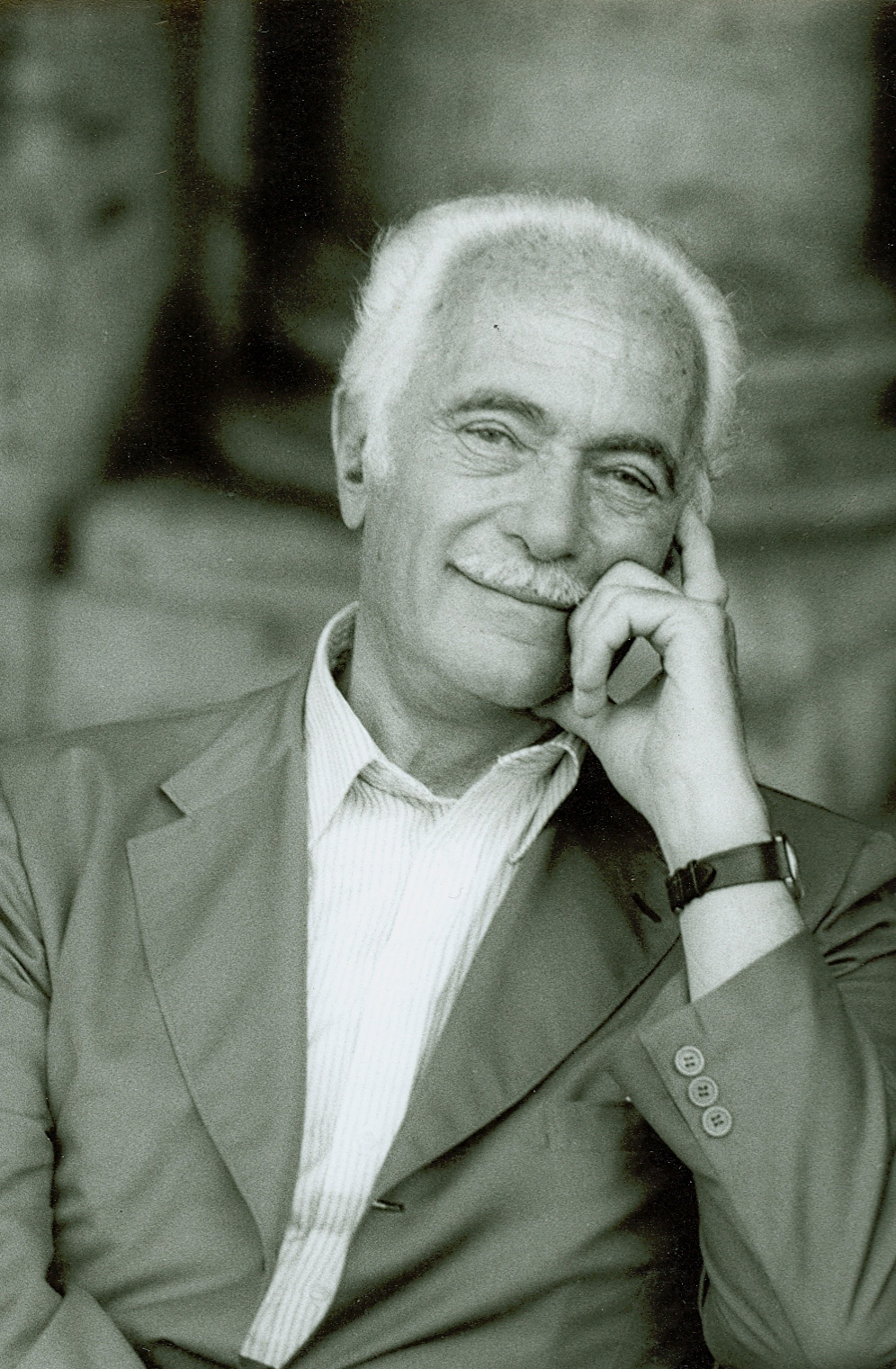

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to "change course":

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

Holotopia is a vision of a future that becomes accessible when proper 'light' has been 'turned on'.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. In view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" were offered as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It ismore attractive than the futures the utopias projected—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not exist. And yet the holotopia is readily attainable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

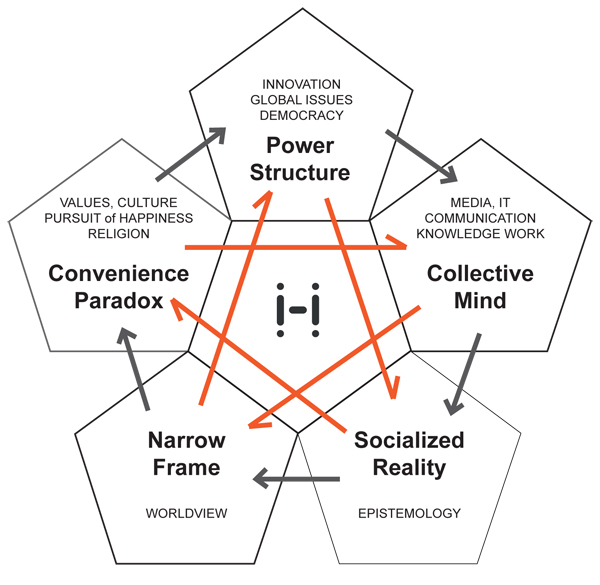

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights.

We applied the holoscope to illuminate five pivotal themes, which determine the "course":

- Innovation—the way we use our growing ability to create, and induce change

- Communication—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is handled

- Epistemology—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning; which determine the relationship we have with information

- Method—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life; or the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it

- Values—the way we "pursue happiness"; or choose "course"

In each case, we found a structural defect, which led to perceived problems. We demonstrated practical ways, partly implemented as prototypes, in which those structural defects can be remedied. We showed that their removal naturally leads to improvements that reach far beyond the solution to problems.

Our federation showed that a lot more than what Peccei was asking for can realistically be achieved.

To establish an analogy between our contemporary cultural situation and the situation at the dawn of the historical "great cultural revival", when Galilei was in house arrest, we looked at five pivotal issues, which are the main aspects of that analogy:

- Innovation (analogy with the Industrial Revolution, which revolutionized the efficiency of labor)

- Communication (analogy with the advent of the printing press, which revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge)

- Epistemology (analogy with the Enlightenment, which enthroned direct experience and reason)

- Methodology (analogy with the advent of science, as an informed and effective way to knowledge)

- Values (analogy with the Renaissance, which empowered our ancestors to seek happiness on the earthly realm)

In each case, we saw that the way we comprehend and handle the issue is ripe to be fundamentally changed.

Innovation (power structure insight). When "free competition" or "the market" steer our growing capability to create and induce change, the systems in which we live and work become power structures—which obstruct natural and human wholeness. A dramatic improvement in efficiency and effectiveness of our work, and of the human condition in general, will result from systemic innovation—when we learn to innovate by making things whole on every scale, and especially on the large scale where changes of institutions or systems are the effect.

Communication (collective mind insight)

We cannot make things whole without seeing them whole.

Our challenge is no longer to mass-produce information, which the printing press made possible, but to co-create meaning. Neil Postman observed:

“We’ve entered an age of information glut. And this is something no culture has really faced before. The typical situation is information scarcity. (…) Lack of information can be very dangerous. (…) But at the same time too much information can be dangerous, because it can lead to a situation of meaninglessness, of people not having any basis for knowing what is relevant, what is irrelevant, what is useful, what is not useful, where they live in a culture that is simply committed, through all of its media, to generate tons of information every hour, without categorizing it in any way for you.”

We have seen that the new media technology enables us to self-organize differently, and and think together, as cells in a human mind do.

Epistemology (socialized reality insight). We will only be able to change our knowledge-work systems when we learn to treat information as we treat other human-made things—by adapting it to the purposes that need to be served.

We have seen that this pivotal and all-important eistemological leap is now mandated on both fundamental and pragmatic grounds. Reification—of worldviews, and of institutions or systems—has been the key instrument of socialization throughout history, by which the power structures imposed their order of things, contrary to our interests, and without our awareness. During the 20th century our self-awareness has evolved dramatically, and we are now able to self-reflect—about the social and cognitive processes by which "realities" are created. We are ready to liberate ourselves—abolishing reification and becoming accountable for the functions or roles that what we do has in our society.

Methodology (narrow frame insight). Science eradicated prejudice and vastly expanded our knowledge—but only there where the methods and interests of its disciplines could be applied. The epistemology change makes it possible to extend the project "science" to include all questions where knowledge can make a difference.

Values (convenience paradox insight). When we illuminate the pivotal issue of values by real information—we see that wholeness, not convenience, must be our goal.

A mission

Large change is easy

The changes the five insights are pointing to are inextricably co-dependent.

We cannot make one of them—without also making the rest!

As we pointed out, also in the above summary, the courses of action he five insights point to are so co-dependent, that any of them requires that we do them all. Norbert Wiener's keyword "homeostasis" can here be used negatively—to point out that an undesirable condition or configuration can also be held in check by the system's tendency to maintain a stable condition, by springing back and nullifying change. A pathological condition can be stable—isn't that what we call "disease"? And isn't that why we don't call a drug a "remedy"—unless it is strong enough to change the body's pathological condition, to reverse its downward course.

Hence what is demanded is a comprehensive and coherent change—of our cultural paradigm as a whole.

To "change course" means to change the paradigm.

The Club of Rome's strategy is further supported by the insight reached in systems sciences—that restoring the ability to shift paradigms is "the most powerful" way to intervene into systems, as Donella Meadows summarized.

Making things whole

What do we need to do to "change course" toward holotopia?

The five insights point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by holotopia's name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

Human development is the key

In the morning of March 14, 1984, the day he passed away, Peccei dictated to his secretary from the hospital bed (as part of "Agenda for the End of the Century"):

Human development is the most important goal.

The theme we are touching upon is more than the relationship we have with information; what we are talking about determines the relationship we have with the world, and with each other. A suitable context for understanding its broader import is what Erich Jantsch called the "evolutionary paradigm". Jantsch explained the evolutionary paradigm via the metaphor of a boat in a river, representing a system (which may at the limit be the natural world, or our civilization). When we use the classical scientific paradigm, we position ourselves above the boat, and aim to look at it "objectively". The classical systems paradigm would position us on the boat, and we would seek ways to steer the boat effectively and safely. But when we use the evolutionary paradigm, we perceive ourselves as—water. We are evolution.

The "human quality" determines the way we are as 'water'—and hence our evolutionary "course", and our future.

Seeing things whole

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To repair the broken tie between information and action; and between information and meaning. Each of the five insights is, before all—an insight. To see the new course, we must be able to create insights.

To be able to "change course", we must be able to see things whole.

In this way a case for our proposal has also been made.

A strategy

We will not solve our problems

A role of the holotopia vision is to fulfill what Margaret Mead identified as "one necessary condition of successfully continuing our existence" (in "Continuities in Cultural Evolution", in 1964—four years before The Club of Rome was founded):

"(W)e are living in a period of extraordinary danger, as we are faced with the possibility that our whole species will be eliminated from the evolutionary scene. One necessary condition of successfully continuing our existence is the creation of an atmosphere of hope that the huge problems now confronting us can, in fact, be solved—and can be solved in time."

Still more concretely, as we have just seen, we undertake to respond to this Mead's call to action, by federating the "tremendous advances in the human sciences":

"Although tremendous advances in the human sciences have been made in the last hundred years, almost no advance has been made in their use, especially in ways of creating reliable new forms in which cultural evolution can be directed to desired goals."

We, however, do not claim, or even assume, that "the huge problems now confronting us can, in fact, be solved".

Hear Dennis Meadows (who coordinated the team that produced The Club of Rome's seminal 1972 report "Limits to Growth") diagnose, recently, that our pursuit of "sustainability" falls short of avoiding the "predicament" that The Club of Rome was warning us about five decades ago:

"Will the current ideas about "green industry", and "qualitative growth", avoid collapse? No possibility. Absolutely no possibility of that. (...) Globally, we are something like sixty or seventy percent above sustainable levels."

We wasted precious time pursuing a dream; hear Ronald Reagan set the tone for it, as "the leader of the free world".

A sense of sobering up, and of catharsis, now needs to reach us from the depth of our problems.

Small things don't matter. Business as usual is a waste of time.

Our very "progress" must now acquire a new—cultural—focus and direction. Hear Dennis Meadows say:

"Will it be possible, here in Germany, to continue this level of energy consumption, and this degree of material welfare? Absolutely not. Not in the United States, not in other countries either. Could you change your cultural and your social norms, in a way that gave attractive future? Yes, you could."

Ironically, our problems can only be solved when we no longer see them as problems—but as symptoms of much deeper cultural and structural defects.

The five insights show that the structural problems now confronting us can be solved.

The holotopia offers more than "an atmosphere of hope". It points to an attainable future that is strictly better than our present.

And it offers to change our condition now—by engaging us in an unprecedentedly large and magnificent creative adventure.

Peccei wrote in One Hundred Pages for the Future (the boldface emphasis is ours):

For some time now, the perception of (our responsibilities relative to "problematique") has motivated a number of organizations and small voluntary groups of concerned citizens which have mushroomed all over to respond to the demands of new situations or to change whatever is not going right in society. These groups are now legion. They arose sporadically on the most variend fronts and with different aims. They comprise peace movements, supporters of national liberation, and advocates of women's rights and population control; defenders of minorities, human rights and civil liberties; apostles of "technology with a human face" and the humanization of work; social workers and activists for social change; ecologists, friends of the Earth or of animals; defenders of consumer rights; non-violent protesters; conscientious objectors, and many others. These groups are usually small but, should the occasion arise, they can mobilize a host of men and women, young and old, inspired by a profound sense of te common good and by moral obligations which, in their eyes, are more important than all others.

They form a kind of popular army, actual or potential, with a function comparable to that of the antibodies generated to restore normal conditions in a biological organism that is diseased or attacked by pathogenic agents. The existence of so many spontaneous organizations and groups testifies to the vitality of our societies, even in the midst of the crisis they are undergoing. Means will have to be found one day to consolidate their scattered efforts in order to direct them towards strategic objectives.

Diversity is good and useful, especially in times of change. The systems scientists coined the keyword "requisite variety" to point out that a variety of possible responses make a system viable, or "sustainable".

The risk is, however, that the actions of "small voluntary groups of concerned citizens" may remain reactive.

From Murray Edelman we adapted the keyword symbolic action, to make that risk more clear. We engage in symbolic action when we act within the limits of the socialized reality and the power structure—in ways that make us feel that we've done our duty. We join a demonstration; or an academic conference. But symbolic action can have only symbolic effects!

We have seen, however, that comprehensive change must be our shared goal.

It is to that strategic goal that the holotopia vision is pointing.

By supplementing this larger strategy, we neither deny that the problems we are facing must be attended to, nor belittle the heroic efforts of our frontier colleagues who are working on their solution.

The Holotopia project complements the problem-based approaches—by adding what is systemically lacking to make solutions possible.

We will not change the world

Like Gaudi's Sagrada Familia, the holotopia is a trans-generational construction project.

It is what our generation owes to future generations.

Our purpose is to begin it.

Margaret Mead left us this encouragement:

"Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has."

Mead explained what exactly distinguishes a small group that is capable of making a large difference:

"(W)e take the position that the unit of cultural evolution is neither the single gifted individual nor the society as a whole, but the small group of interacting individuals who, together with the most gifted among them, can take the next step; then we can set about the task of creating the conditions in which the appropriately gifted can actually make a contribution. That is, rather than isolating potential "leaders," we can purposefully produce the conditions we find in history, in which clusters are formed of a small number of extraordinary and ordinary men and women, so related to their period and to one another that they can consciously set about solving the problems they propose for themselves."

This—capability to self-organize—is where "human quality" is needed. And that is what we've been lacking!

The five insights have shown that again and again. Our stories are deliberately chosen to be a half-century old—and demonstrate that the "appropriately gifted" have already offered us their gifts. But giants and visionary ideas no longer have a place in the order of things we are living in.

We live in an institutional ecology that gives us "competitive advantage" only if we make ourselves small, sidestep "ideals", and become "little cogs that mesh together". Through innumerably many 'carrots and sticks' we have internalized the little institutional man who fits in, and keeps our larger self on a leash (see this re-edited and pointedly repetitive excerpt from the animated film The Incredibles; its ending will suggest what we must find courage to do).

Our core strategy is to change the institutional ecology that makes us small.

We will not sidestep that goal by adapting to the existing order of things, treating the development of holotopia as "our project" and trying to make it "successful"—within that very order of things we have undertaken to change.

We insist on considering the development of the holotopia as our generation's opportunity and obligation—and hence as your project as much as ours. Our core strategy is to inspire and empower you to contribute to it and make a difference.

We will not change the world.

You will.

Tactical assets

The Holotopia prototype is conceived as a collaborative strategy game, where we make tactical moves toward the holotopia vision.

We make this 'game' engaging and smooth by contributing the following tactical assets.

This text will be corrected, improved and completed by the end of 2020. What is above is hopefully readable; what follows is a rough sketch.

A space

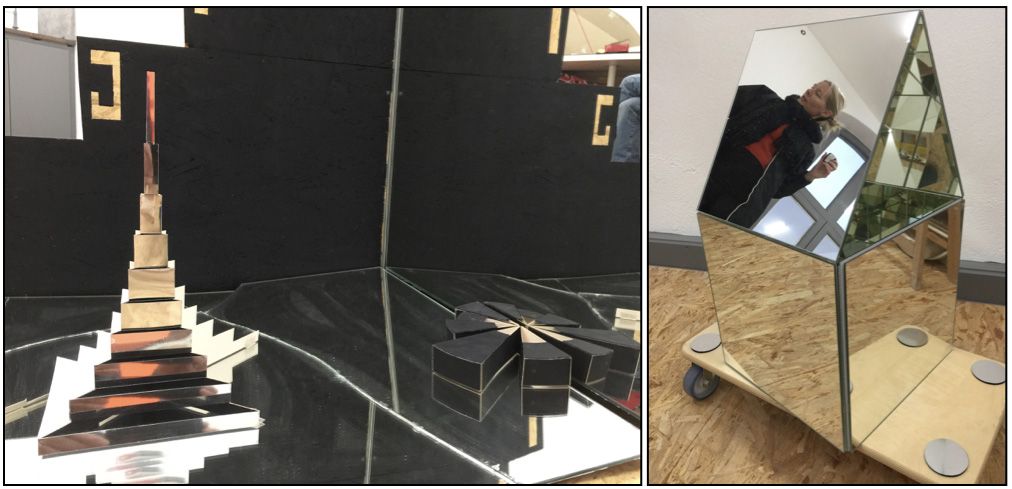

Holotopia is an art project.

The transformative space created by our "Earth Sharing" pilot project, in Kunsthall 3.14 art gallery in Bergen, Norway.

The very thought of "a great cultural revival" brings to mind the image of Michelangelo painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and in the midst of an old order of things manifesting a new one. When Marcel Duchamp exhibited the urinal, he challenged both the meaning of art and its limits. But the deconstruction of tradition has meanwhile been completed, and the time is now to construct.

What sort of art will manifest the holotopia?

In "Production of Space", Henri Lefebvre offered an answer—which we'll here summarize in holotopia's buddying vernacular.

The core problem with the social system we are living in, Lefebvre observed, is that our past activity, crystalized as power structure, keeps us "alienated" from our intrinsically human quest of wholeness. In our present conditions, "what is dead takes hold of what is alive". Lefebvre proposed to turn this relationship upon its head:

"But how could what is alive lay hold of what is dead? The answer is: through the production of space, whereby living labour can produce something that is no longer a thing, nor simply a set of tools, nor simply a commodity."

As an initiative in the arts, Holotopia produces spaces where what is alive in us can overcome what is making us dead.

Five insights

While the role of the arts is to communicate and create, to put 'the dot on the i', the five insights model the holotopia's knowledge base. They ensure that what we communicate and create reflects the state of the art of knowledge in relevant areas of interest. Together, they compose a complete 'i', or 'lightbulb', or "headlights and steering", or "communication and control".

The symbolic language of the arts can condense the five insights to images and objects, place them into physical reality and our shared awareness—as the above paper models may suggest.

The elephant

The role of this metaphorical image, of an invisible elephant, is to point to a quantum leap in relevance and interest, which specific academic and other insights can acquire when presented in the context of "a great cultural revival".

There is an "elephant in the room", waiting to be discovered.

Imagine the 20th century's thinkers touching this elephant: We hear them talk about "the fan", "the water hose" and "the tree trunk". But they don't make sense, and we ignore them.

Everything changes when we realize that what they are really talking about are 'the ear', 'the trunk' and 'the leg' of an immensely large and exotic animal—which nobody has yet seen!

To make headway toward holotopia, we orchestrate 'connecting the dots'.

By manifesting the elephant, we restore agency to information and power to knowledge.

The structuralists undertook to bring rigor to the study of cultural artifacts. The post-structuralists "deconstructed" their efforts, by observing that there is no such thing as "real meaning"; and that the meaning of cultural artifacts is open to interpretation. We can now take this evolution a step further.

What interests us is not what, for instance, Bourdieu "really saw" and wanted to communicate; with the post-structuralists, we acknowledge that even Bourdieu would not be able to tell us that, if he were still around. Yet he undoubtedly saw something that invited a different way to see the world; and undertook to understand it and communicate it by taking recourse to the only paraigm that was available—the old one.

We give the study of cultural artifacts new relevance and rigor—by considering them as signs on the road, which point to a paradigm that now wants to emerge.

Stories

Our stories are vignettes. This in principle journalistic technique allows us to render academic and other insights in a way that makes them palatable to public, and usable to journalists and artists. A vignette is a meme, which may do more than convey ideas.

We here illustrate this technique by a single example, The Incredible History of Doug Engelbart. In a fractal-like way, this story illustrates some of the "incredible" sides of the emerging paradigm, notably its difficulty to be seen and understood. The story will be told in the second book of the Holotopia series (with title "Systemic Innovation" and subtitle "Cybernetics of Democracy"), and here we give only highlights.

Having told variants of that story multiple times, we found several ways to begin it. One of them—which we used to launch the "Doug Engelbart´s Unfinished Revolution - The Program for the Future" PhD seminar at the University of Oslo, and the "Leadership of Systemic Innovation" PhD program at the Buenos Aires Institute of Technology—is to frame it as a puzzle: The inventor whose inventions marked the computer era, whom the Silicon Valley recognized as its giant in residence, died in 2013 feeling that he had failed (we offer this fifteen-minute recording, and apologize for the echo). In 2010, Engelbart answered the question "How much of your ideas, Doug, have been implemented?" half-jokingly, by "3.6%".

What is the remaining "96.4%"? What Engelbart's game-changing ideas do we still ignore?

Another way is to tell the story chronologically: In December 1950, a 25-year old engineer was looking at his future career: He had excellent education; he was employed by (what later became) NASA; he was engaged to be married... He saw his future as a straight path to retirement. And he didn't like what he saw. "A man must have a purpose!" Engelbart observed. So right there and then he decided that he would give his career a purpose that would maximize its benefits to mankind.

Engelbart spent three month thinking about the best way to do that. Then he had an epiphany.

Engelbart's thinking, which led to his epiphany, was manifestly systemic.

Did Engelbart really find the best way to improve the human condition?

The title slide of Engelbart's presentation at Google (inserted into Knowledge Federation's template).

The third way is to begin at the end—and tell about Engelbart's "A Call to Action" panel presentation at Google, in 2007; as we did in this blog report. Doug was then at the end of his career, ready to give his last message to the world. But somehow—and no doubt incredibly—the title slide and with it his "call to action"; and the first four slides, which provided the necessary context for understanding the rest—were not even shown! The Youtube page with the recording of this event bears the title "Inventing the Computer Mouse". Is that the achievement by which Engelbart should be remembered?

What Engelbart contributed was the elephant, not (just) the mouse!

The Incredible History of Doug is the story of a contemporary Galilei—who is kept 'in house arrest' by the narrowness of our vision.

Its incredible side mirrors the rest of us—as a generation of people who have become so admirably technology-savvy; and so incredibly idea-blind!

Wikipedia illustrates this vividly, by writing (in its article about "The Mother of All Demos"): "Prior to the demonstration, a significant portion of the computer science community thought Engelbart was "a crackpot"." Yes, the demonstration was an impressive feat of technology; the ideas that were behind it are still ignored.

So what were Engelbart's important ideas?

One of them we have seen: The collective mind paradigm. To give our systems the faculty of vision—and make them, and us, capable of following a sane course. That idea we also offered as the solution to our "puzzle" (hear this recording).

But there was an even larger one.

In 1962, six years before Jantsch and others would convene in Bellatgio, Italy, Engelbart contributed an original method for systemic innovation. It was the very "evolutionary guidance" that our society was in need for..

Let us illustrate it by using it to explain Engelbart's "call to action".

Engelbart used this slide to explain his systemic innovation method.

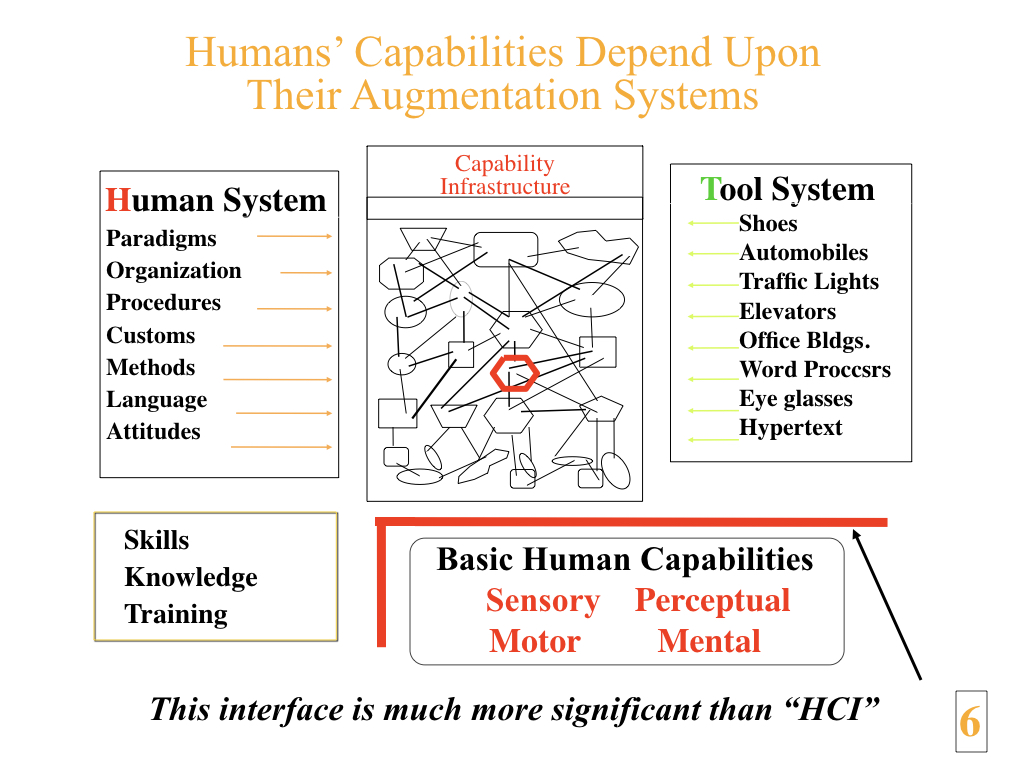

Engelbart's method, which he called "augmentation", was based on what he called "capability hierarchy". You'll understand it if you imagine a human being with no technology or culture—and all the rest comprising various ways to "augment" his innate capabilities, individual and collective. The capability hierarchy has two sides or aspects, the "human system" and the "tool system". The capability to communicate in writing, for example, requires certain tool system components such as the clay tablets or the printing press; and certain human system components such as literacy and education.

A good way to innovate, Engelbart observed, is by identifying a capability that has become necessary; and the human system and tool system components that would make it possible.

It was in this way that Engelbart identified the capability "to cope with the complexity and urgency of problems" as the one which must be given priority.

And the network-interconnected interactive digital media technology as the enabling tool.

What was still missing—and what his call to action was about—was the capability to "bootstrap" the corresponding "human system" change.

But isn't that what we've been talking about all along?

These were, however, Engelbart's largest and most basic ideas—in the context of which his numerous technical inventions must be understood. We mention two of them as examples.

The idea of the "open hyperdocument system" can be comprehended if we think about document processing as it is today: Microsoft Word, Adobe Photoshop... Those are tools that

- create and process traditional document types (books, articles, photographs...)

- by using proprietary document formats

The open hyperdocument system is what is needed to enable the knowledge work media and processes to evolve—and to enable us to substitute 'the lightbulb' for 'the candle'.

Engelbart experimented extensively with hierarchical and flexible information representation—which is, as we have seen, what 'the lightbulb' needs to be like.

The second example we want to mention is a collection of keywords and templates for knowledge-work infrastructures that may compose a collective mind. Examples are the "networked improvement community" and the "A, B and C levels" of creative activity. Any human activity has the hands-on "A-level", where people for instance make shoes, and the "B-level" where they improve the shoes and the shoe making. The goal of the "C-level" activity is to improve the improvers. Engelbart observed that while B-level activities tend to be task-specific and hence different from one other, the C-level activities tend to be uniform across applications; and that this commonality of structure offered an uncommonly fertile ground for creative action. Engelbart envisioned that the B-level work would be organized in terms of "networked improvement communities" or "NICs"; and that the C-level work would be structured as a "NIC of NICs".

Knowledge Federation prototypes this idea.

The mirror

The mirror lands itself to artistic creation; snapshots from Vibeke Jensen's Berlin studio.

Let us begin with the obvious: The mirror is a visual and symbolic object par excellence. In holotopia, however, its symbolism is further enriched by a wealth of concrete interpretations.

The mirror reflects the holotopia's enchanting, 'magical' touch.

There is an unexpected, wonderful and seemingly magical way out of the "problematique"; a natural and effective way to transform our situation. We do not need to colonize another planet (we would anyhow bring to it our cultural malaise). We can move to a different reality here and now—by seeing the world differently. Or metaphorically—by stepping through the mirror.

The mirror tells us that we need to look at the world by putting ourselves into the picture.

The mirror makes us aware of our socialized cognitive biases, and instructs us to use knowledge to see both ourselves and the world.

It has been pointed out that Donald Trump does not believe in science. But when we carefully examine ourselves in the mirror, we see don't do that either! Little Greta Thunberg does. She lives in the reality created by the scientists, and acts in a way that is consistent with it. But she was diagnosed of Asperger syndrome, and doesn't count as a counterexample. The truth is that all of us "normal" humans live in a socialized reality, created through body-to-body interaction; which is now vastly augmented by ever-present immersive media.

The mirror symbolizes the abolition of reification, and the ascent of accountability. By liberating ourselves from reification, we liberate ourselves from socialized reality and from power structure. We become empowered to create the way in which we see the world, to change our institutions, to begin "a great cultural revival".

The mirror is also a symbol of academic transformation.

In addition to the 'magical' solution to the "problematique", the mirror also has a sober side—where it reflects the need for academic self-reflection and transformation. This need is imposed academically and rigorously by the knowledge of knowledge we own.

Being a revolution of awareness, the holotopia has in academia its most powerful ally.

We defined the academia as "institutionalized academic tradition" to make that point transparent. And we made Socrates be the icon of academia, as its intellectual father. By telling the story Plato told in Apology, we show that the academia's point of inception was an act of liberation from socialized reality; Socrates used the dialogue as technique to shake off the "doxa" of the day. We created a way of looking at the contemporary university as an institutionalization of that tradition.

At first glance, our job now may seem so much easier than what Socrates and Galilei had to do—because the academic tradition is in power!

But there's a rub: Ironically, by being in power, the academic tradition is also part of the power structure! It is both a 'turf' in itself—and part of a larger 'turf'. This is easily seen if we acknowledge that, culture-wise, anything goes as long as it doesn't violate "scientific truth". A division of power is established similar in spirit to what existed in Galilei's time—albeit completely different in implementation.

Can we mobilize enough academic "human quality" to once again make the kind of difference that the academic tradition is called upon to make?

Finally, the mirror tells us most concretely how to begin "a great cultural revival", and make decisive progress toward developing "human quality". "Know thyself" has always been the battle cry of human cultivation. And isn't that what the mirror most naturally reflects?

We now have the great insights of 20th century science and philosophy, and the heritage of the world traditions—to help us know ourselves!

All we need to do is restore knowledge to power.

The dialog

The dialog, just as the mirror, is an entire aspect of the holotopia. This keyword defines an angle of looking from which the holotopia as a whole can be seen, and needs to be seen.

The mirror and the dialog are inextricably related to one another: Our invitation is not only to self-reflect, but also and most importantly to have a dialog in front of the mirror. The dialog is not only a praxis, but also an attitude. And the mirror points to the core element of that attitude—which David Bohm called "proprioception". But let's return to Bohm's ideas and his contribution to this timely cause in a moment.

The dialog is a key element of the holotopia's tactical plan: We create prototypes, and we organize dialogs around them, as feedback mechanisms toward evolving them further. And this dialog itself, as it evolves—turns us who participate in it into bright new 'headlights'!

Everything in our Holotopia prototype is a prototype. And no prototype is complete without a feedback loop that reaches back into its structure, to update it continuously. Hence each prototype is equipped with a dialog.

This point cannot be overemphasized: Our primary goal is not to warn, inform, propose a new way to look at the world—but to change our collective mind. Physically. Hands-on.

The dialog is an instrument for changing our collective mind.

The dialog, even more than the mirror, brings up an association with the academia's inception. Socrates was not convincing people of a "right" view to see "reality"; he was merely engaging them in a self-reflective dialog, the intended result of which was to see the limits of knowledge—from which the change of what we see as "reality" becomes possible.

Let us begin this dialog about the dialog by emphasizing that the medium here truly is the message: As long as we are having a dialog, we are making headway toward holotopia. And vice-versa: when we are debating or discussing our own view, aiming to enforce it on others and prevail in an argument, we are moving away from holotopia—even when we are using that method to promote holotopia itself!

The attitude of the dialog here follows from the fundamental premises, which are part of the socialized reality and the narrow frame insights—and which are axiomatic to holotopia. Hence coming to the dialog 'wearing boxing gloves' (manifesting the now so common verbal turf strife behavior) is as ill-advised as making a case for an academic result by arguing that it was revealed to the author in a vision.

But what is the dialog?

Instead of giving a definitive answer—let us turn this keyword, dialog, into an abstract ideal goal, to which we will draw closer and closer by experimenting, and evolving. Through a dialog. We offer the following stories as both points of reference, and as illustration of the kind of difference that the dialog as new way to communicate can mean, and make.

David Bohm's "dialogue"

While through Socrates and Plato the dialog has been a foundation stone of the academic tradition, David Bohm gave this word a completely new meaning—which we have undertaken to develop further. The Bohm Dialogue website provides an excellent introduction, so it will suffice to point to it by echoing a couple of quotations. The first is by Bohm himself.

There is a possibility of creativity in the socio-cultural domain which has not been explored by any known society adequately.

We let it point to the fact that to Bohm the "dialogue" was an instrument of socio-cultural therapy, leading to a whole new co-creative way of being together. Bohm considered the dialogue to be a necessary step toward unraveling our contemporary situation.

The second quotation is a concise explanation of Bohm's idea by the curators of Bohm Dialogue website.

Dialogue, as David Bohm envisioned it, is a radically new approach to group interaction, with an emphasis on listening and observation, while suspending the culturally conditioned judgments and impulses that we all have. This unique and creative form of dialogue is necessary and urgent if humanity is to generate a coherent culture that will allow for its continued survival.

As this may suggest, the dialog is conceived as a direct antidote to power structure-induced socialized reality.

Carl Jung's shadow

Carl Jung pointed to a useful insight for understanding the dialog, by his own lead keyword "shadow". In a non-whole world, we become "large" by ignoring or denying or "repressing" parts of our wholeness, which become part of our "shadow". The larger we are, the larger the "shadow". It follows us, scares us, annoys us. And it contains what we must integrate, to be able to grow.

The dialog may in this context be understood as a therapeutic instrument, to help us discharge and integrate our "shadow".

Dialog and epistemology

Bohm's own inspiration (story has it) is significant. Allegedly, Bohm was moved to create the "dialogue" when he saw how Einstein and Bohr, who were once good friends, and their entourages, were unable to communicate at Princeton. Allegedly, someone even made a party and invited the two groups, to help them overcome their differences, but the two groups remained separated in two distinct corners of the room.

The reason why this story is significant is the root cause of the Bohr-Einstein split: Einstein's "God does not play Dice" criticism of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory; and Bohr's reply "Einstein, stop telling god what to do!" While in our prototype Einstein has the role of the icon of "modern science", in this instance it was Bohr and not Einstein who represented the epistemological position we are supporting. But Einstein later reversed his position— in "Autobiographical Notes". This very title mirrors Einstein as an artist of understatement; "Autobiographical Notes" is really a statement of Einstein's epistemology—just as "Physics and Philosophy" was to Heisenberg. While the fundamental assumptions for the holoscope have been carefully federated, it has turned out that federating "Autobiographical Notes" is sufficient, see Federation through Images).

The point may or may not be obvious: Even to Einstein, this icon of "modern science", the dialog was lacking to see that we just cannot "tell God what to do"; that the only thing we can do is observe the experience—and model it freely.

But Einstein being Einstein—he finally did get it. And so shall we!

Dialog and creativity

Bohm's experience with the "dialogues" made him conclude that when a group of people practices it successfully, something quite wonderful happens—a greater sense of coherence, and harmony. It stands to reason that the open and humble attitude of the dialog is an important or a necessary step toward true creativity.

And creativity, needless to say, is yet another key aspect of holotopia, and a door we need to unlock.

We touched upon the breadth and depth of this theme by developing our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity prototype—and we offer it here to prime our future dialogs about it.

Dialog and The Club of Rome

There is a little known red thread in the history of The Club of Rome; the story could have been entirely different: Özbekhan, Jantsch and Christakis, who co-founded The Club with Peccei and King, and wrote its statement of purpose, were in disagreement with the course it took in 1970 (with The Limits to Growth study) and left. Alexander Christakis, the only surviving member of this trio, is now continuing their line of work as the President of the Institute for 21st Century Agoras. "The Institute for 21st Century Agoras is credited for the formalization of the science of Structured dialogic design." (Wikipedia).

Bela H. Banathy, whom we've mentioned as the champion of "Guided Evolution of Society" among the systems scientists, extensively experimented with the dialog. For many years, Banathy was staging a series of dialogs within the systems community, the goal of which was to envision social-systemic change. With Jenlink, Banathy co-edited two invaluable volumes of articles about the dialogue.

Dialog and democracy

In 1983, Michel Foucault was invited to give a seminar at the UC Berkeley. What will this European historian of ideas par excellence choose to tell the young Americans?

Foucault spent six lectures talking about an obscure Greek word, "parrhesia".

[P]arrhesiastes is someone who takes a risk. Of course, this risk is not always a risk of life. When, for example, you see a friend doing something wrong and you risk incurring his anger by telling him he is wrong, you are acting as a parrhesiastes. In such a case, you do not risk your life, but you may hurt him by your remarks, and your friendship may consequently suffer for it. If, in a political debate, an orator risks losing his popularity because his opinions are contrary to the majority's opinion, or his opinions may usher in a political scandal, he uses parrhesia. Parrhesia, then, is linked to courage in the face of danger: it demands the courage to speak the truth in spite of some danger. And in its extreme form, telling the truth takes place in the "game" of life or death.

Foucault's point was that "parrhesia" was an essential element of Greek democracy.

This four-minute digest of the 2020 US first presidential debate will remind us just how much the spirit of dialog is absent from modernity's oldest democracy; and from political discourse at large.

Dialog and new media technology

A whole new chapter in the evolution of the dialogue was made possible by the new information technology. We illustrate an already developed research frontier by pointing to Jeff Conklin's book "Dialogue Mapping: Creating Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems", where Bohm dialogue tradition is combined with Issue Based Information Systems (IBIS), which Kunz and Rittel developed at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

The Debategraph, which we already mentioned, is transforming our collective mind hands-on. Contrary to what its name may suggest, Debategraph is an IBIS-based dialog mapping tool. While he was the Minister for Higher Education in Australian government, Peter Baldwin saw that political debate was not a way to understand and resolve issues. So he decided to retire from politics, and with David Price co-founded and created Debategraph to transform politics, by changing the way in which issues are explored and decisions are made.

In Knowledge Federation, we experimented extensively with turning Bohm's dialog into a 'high-energy cyclotron'; and into a medium through which a community can find "a way to change course". The result was a series of so-called Key Point Dialogs. An example is the Cultural Revival Dialog Zagreb 2008. We are working on bringing its website back online.

Dialog as a tactical asset

When it comes to using the dialog as a tactical asset—as an instrument of cultural change toward the holotopia—two points need to be emphasized:

- We define the dialog, and we insist on having a dialog

- We design our situations, and we use the media, in ways make that deviations from the dialog obvious

When a dialog is recorded, and placed into the holotopia framework, violations become obvious—because the attitude of the dialog is so completely different! We may see how this made a difference in the Club of Rome's history, where the debate gave unjust advantage to the homo ludens turf players—who don't use "parrhesia", but say whatever will earn them points in a debate, and smile confidently, knowing that the "truth" of the power structure, which they represent, will prevail! The body language, however, when placed in the right context, makes this game transparent. See [this example, where Dennis Meadows is put off-balance by an opponent.

Hence the dialog—when adopted as medium, and when mediated by suitable technology and camera work—becomes the mirror; it becomes a new "spectacle" (in Guy Debord's most useful interpretation of this word). We engage the "opinion leaders", and use the dialog to re-create the conventional "reality shows"—in a manner that shows the contemporary realities in a way in which they need to be shown:

- When a dialog is successful, the result is timely and informative: We witness how our understanding and handling of core social realities are changing

- When unsuccessful, the result is timely and informative in a different way: We witness the resistance to change; we see what is holding us back

Everything in holotopia is a potential theme for a dialog. Indeed, everything in our holotopia prototype is a prototype; and a prototype is not complete unless there is a dialog around it, to to keep it evolving and alive.

In particular each of the five insights will, we anticipate, ignite a lively conversation.

We are, however, especially interested in using the five insights as a framework for creating other themes and dialogs. The point here is to have informed conversations; and to show that their quality of being informed is what makes all the difference. And in our present prototype, the five insights symbolically represent that what needs to be known, in order to give any age-old or contemporary theme a completely new course of development.

The five insights, and the ten direct relationships between them, provide us a frame of reference—in the context of which both age-old and contemporary challenges can be understood and handled in entirely new ways.

Here are some examples.

How to put an end to war?

What would it take to really put an end to war, once and for all?

The five insights allow us to understand the war as just an extreme case among the various consequences of our general evolutionary course, by "the survival of the fittest"—where the populations that developed armies and weapons had "competitive advantage" over those who "turned the other cheek". It is that very evolutionary course that the Holotopia project undertakes to change.

We offered the Chomsky–Harari–Graeber thread as a way to understand the evolutionary course we've been pursuing, and the consequences it had. Noam Chomsky here appears in the role of a linguist—to explain (what he considers a revolutionary insight reaching us from his field) that the human language did not develop as an instrument of communication, but of worldview sharing. Yuval Noah Harari, as a historian, explains why exactly that capability made us the fittest among the species, fit to rule the Earth. David Graeber's story of Alexander the Great illustrates the consequences this has had—including the destruction of secular and sacral culture, and turning free people into slaves.

We then told about Joel Bakan's "The Corporation", to show that while the outlook of our society changed since then beyond recognition—the nature of our cultural and social-systemic evolution, and its consequences, remained in principle the same.

We could have, however, taken this conversation in the making in another direction—by talking about the meeting between Alexander and Diogenes; and by doing that reaching another key insight.

This part of the conversation between Alexander and Diogenes (quoted here from Plutarch) is familiar :

And when that monarch addressed him with greetings, and asked if he wanted anything, "Yes," said Diogenes, "stand a little out of my sun."

In his earlier mentioned lectures about "parrhesia", Foucault tells a longer and more interesting story—where Diogenes (who has the most simple lifestyle one could imagine) tells Alexander (the ruler of the world) that he is "pursuing happiness" in a wrong direction. You are not free, Alexander, Diogenes tells him; you live your life in fear; you hold onto your royal role by force:

" I have an idea, however, that you not only go about fully armed but even sleep that way. Do you not know that is a sign of fear in a man for him to carry arms? And no man who is afraid would ever have a chance to become king any more than a slave would."

Alienation

This theme offers to reconcile Karl Marx with "the 1%", the Western philosophical tradition with the Oriental ones, and the radical left with Christianity.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy introduces "alienation" in a way that is easily integrated in the order of things represented by holotopia:

"The concept of alienation identifies a distinct kind of psychological or social ill; namely, one involving a problematic separation between a self and other that properly belong together."

Or to paraphrase this in the vernacular of holotopia:

Alienation is what separates us from wholeness.

We offer the Hegel-Marx-Debord thread as a way put the ball in play for a conversation about this theme. This thread has not yet been written, so we here sketch it briefly.

To Hegel, "alienation" was a life-long pursuit. The way we see the world is subject to errors, Hegel observed; so we are incapable of seeing things whole, in order to make them whole. Hegel undertook to provide a remedy, by developing a philosophical method.

Marx continued Hegel's pursuit in an entirely different way. Having seen the abysmal conditions that the mid-19th century workers lived in, he grew diffident of philosophizing and of his own class background. The working class—the majority of humans—cannot pursue wholeness, because they must labor under conditions that someone else created for them. Science liberated us from so many things, Marx also observed, in the spirit of his time—why not apply its causal thinking to the societal ills as well? Logically, he identified "expropriation" as necessary goal; and a revolution as necessary means. Seeing that the religion hindered the working class from fulfilling its historical revolutionary role, Marx chose to disqualify it by calling it "the opium of the people".

Marx was of course in many ways right; but he made two errors. The first we'll easily forgive him, if we take into account that he too, unavoidably perhaps for a rational thinker in his age, looked at the world through the narrow frame: He sidestepped "human quality", and adopted "instrumental thinking". Where Marx's agenda was successful, "the dictatorship of the proletariat" ended up being only—the dictatorship! In the rest of world, the "left" understood that to have power, it must align itself with power structure—and became just another "right"!

The second error Marx made was to ignore that also the capitalists were victims of power structure. They too would benefit from pursuing wholeness instead of power and money. Gandhi, of course, saw that, and that was his great contribution to the methodology of group conflict resolution. But Gandhi's thinking was of holistic-Oriental, not instrumental.

Having failed to see there was a "winning without fighting" strategy—the left and remained on the losing side of the power scale until this day.

An interesting side effect of this development was that, having bing disowned by the "left", Christ became an emblem of the "right"—which is ironic: Jesus was a revolutionary! His only reported act of violence was "expelling the money changers from the temple of God".

Guy Debord added to this theme a whole new chapter, by observing that the immersive audio-visual technology gave to alienation a whole new medium and course—which Marx could not have possibly predicted.

By placing this conversation in the context of the convenience paradox insight on the one side, and the power structure insight on the other, we recognize the power structure—which includes all of us—as "enemy"; and wholeness—for all of us—as goal.

Enlightenment 2.0

By placing this conversation about the reissue of "enlightenment" in the context of the convenience paradox insight and the collective mind insight, two most interesting venues for transdisciplinary cross-fertilization are opened up.

One of them is to use knowledge federation and contemporary media technology, powered by artistic and other techniques, to federate the kind of insights that can make the convenience paradox transparent, and inform "a great cultural revival".

The other one is to use the insights into the nature of human wholeness to inform the development and use of contemporary media technology. How do computer games, and the ubiquitous advertising, really affect us? In Intuitive introduction to systemic thinking we offered a couple of further interesting historical reference points, to motivate a reflection about this theme.

Here Gregory Bateson's important keyword "the ecology of the mind", and Neil Postman's closely related one "media ecology", can set the stage for federating a human ecology that will make us spirited and enlightened, not despondent and dazzled.

Academia quo vadis?

This title is reserved for the academic self-reflective dialog in front of the mirror, about the university's social role, and future.

A number of 20th century thinkers claimed that the development of transdisciplinarity was necessary; Erich Jantsch, for instance, who saw the "inter- and transdisciplinary university" as the core element of our society's "steering and control', necessary if our civilization will gain control over its newly acquired power, and steer a viable course; Jean Piaget saw it from the point of view of cognitive psychology (although Piaget is usually credited for coining this keyword, Jantsch may have done that before him); Werner Heisenberg saw it from the fundamental angle of "physics and philosophy", as we have seen.

By placing the conversation about the academia's future in the context of the socialized reality insight and the narrow frame insight, and in that way making it informed by a variety of more detailed insights, we showed that the epistemological and methodological developments that took place in the last century enable transdisciplinarity; that its development can be seen as the natural and necessary next step in the university institution's evolution; and that our global condition mandates that we take that step.

Jey Hillel Bernstein wrote in a more recent survey:

"In simultaneously studying multiple levels of, and angles on, reality, transdisciplinary work provides an intriguing potential to invigorate scholarly and scientific inquiry both in and outside the academy."

This conversation may take a number of different directions.

One of them is to be a dialog about knowledge federation as a concrete prototype of a "transdiscipline". Such a dialog is indeed the true intent of our proposal; we are not proposing another methodological and institutional 'dead body'—but a way for the university to evolve its institutional organization and its methods, by federating insights into an evolving prototype.

A completely one would be to discuss the university's ethical norms and guidance. Should we be pursuing our careers in traditional disciplines? Or consider ourselves as parts in a larger whole, and adapt to that role?

This particular approach to our theme, however, also has a deeper meaning; and that's the one that its title is pointing to. Nearly two thousand years ago the ethical and institutional foundation of the Roman Empire was shaking, and the Christian Church stepped into the role of a guiding light. Can the university assume that role today?

Keywords

A warning reaches us from sociology.

Beck explained his admonition:

"Max Weber's 'iron cage' – in which he thought humanity was condemned to live for the foreseeable future – is for me the prison of categories and basic assumptions of classical social, cultural and political sciences."

Isn't this a wonderful way to combine together several of our insights!

The message of the Modernity ideogram to begin with—that our traditional concepts will not serve us to understand and handle the post-traditional, fast-changing realities that surround us. That our inherited ways of looking at the world keep us driving by looking at rear-view mirror, as McLuhan phrased it, or in socialized reality as we did. And then the "iron cage" metaphor also points to the disempowerment we attempted to illuminate by elaborating on the all-important relationship between socialized reality and power structure.

We proposed the creation of keywords as remedy. By applying truth by convention, we can create completely new ways of looking at the world; we can give our old concepts new meanings. <p> <p>An example we have seen (while discussing the socialized reality insight) is the definition of design as "alternative to tradition". This definition alone allows us "to understand the transformation into the post-traditional cosmopolitan world we live in today" in a way that shows how our thinking and acting needs to change. In a post-traditional culture we can no longer assume that our culture is taking us to wholeness; we must take charge—by consciously making things whole. Keywords such as design, and systemic innovation, mean in essence exactly that—how our thinking and acting needs to change in our new situation.

The very creation of keywords, by using truth by convention, is the way to design concepts. It is the handling of language that suits the post-traditional order of things—just as reification is the approach that the tradition depends on.

Our collection of keywords—once it is organized and presented—will provide an excellent entry point to holotopia as a whole. We here discuss only three—which will illustrate in a fractal-like way illustrate a spectrum of issues that the creation of keywords addresses.

Culture

In "Culture as Praxis", Zygmunt Bauman surveyed a large number of historical definitions of culture, and concluded that they are too diverse to be reconciled.

We do not know what "culture" means!

Not a good venture point for developing culture as praxis (informed practice).

The keywords do not tell us what the defined concept "really means". Rather, a keyword defines a way of looking or scope. We may also think of it as a projection plane, where we project the thing being defined to see one of its sides or aspects.

Our definition of culture defines an aspect of culture.

We defined culture as "cultivation of wholeness", and cultivation by analogy with planting and watering a seed (which suits also the etymology of "culture") . In this way we defined a specific way of looking at culture, and pointed to its specific aspect—exactly the one that we tended to ignore, while we looked at it through the narrow frame. No amount of dissecting and studying a seed would suggest that it needs to be planted and watered; the difference between an apple eaten up and the seeds thrown away—and a tree full of apples each Fall—is made by relying on the experience of others who have undergone this process, and seen it work.

There is, however, an obvious difference between the two kinds of cultivation, the agricultural and cultural one: In this latter one, both 'seeds' and 'trees' are inside ourselves, and hence invisible. This has historically presented an insurmountable challenge, to communicate cultural insights. But to us this is also a most wonderful opportunity—because we have undertaken to develop communication consciously, by tailoring it to what needs to be communicated.

Béla H. Bánáthy opened "Guided Evolution of Society" by saying:

In the course of the evolutionary journey of our species, there have been three seminal events. The first occurred some seven million years ago, when our humanoid ancestors silently entered on the evolutionary scene. Their journey toward the second crucial event lasted more than six million years, when—as the greatest event of our evolutionary history—Homo sapiens sapiens, started the human revolution, the revolutionary process of cultural evolution. Today, we have arrived at the threshold of the third revolution: the revolution of conscious evolution, where it becomes our responsibility to enter into the evolutionary design space and guide the evolutionary journey of our species.

It seems only fitting that this "third revolution" will require that we adapt the way we use our language as well.

Addiction

Here too we want to emphasize the way of defining addiction. The traditional definitions would tend to identify certain activities such as gambling, or certain things such as opiates, as addictions. But selling addictions is a famously lucrative yet destructive line of business. What will hinder businesses from using new technologies and create a variety of completely new addictions?

The evolution gave us senses and emotions to guide us to wholeness. The technology made it possible to deceive our senses—and create pleasurable things and activities that take us away from wholeness. They are addictions. The refined, industrial sugar—as the pleasurable substance extracted from a plant, which can then be added to almost anything to make it palatable—might serve as an explanatory template.

By defining addiction as a pattern, we made it possible to identify it as an aspect of otherwise useful activities and things. To make ourselves and our world whole, even subtle addiction will need to be taken care of.

From a large number of obvious or subtle addictions, we here mention only pseudoconsciousness defined as "addiction to information". Consciousness of one's situation and surroundings is, of course, a necessary condition for wholeness. In civilization we can, however, drown this need in facts and data, which give us the sensation of knowing—without telling us what we really need to know, in order to be or become whole.

Religion

In "Physics and Philosophy" Werner Heisenberg described some of the consequences of the narrow frame:

It was especially difficult to find in this framework room for those parts of reality tht had been the object of the traditional religion and seemed now more or less only imaginary. Therefore, in those European countries in which one was wont to follow the ideas up to their extreme consequences, and open hostility of science toward religion developed (...). Confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind.

If you too happen to be affected by the narrow frame in this way, it may be best to consider our way of handling concepts as 'recycling'—as giving old words new meaning, and hence restoring them to the kind of function they need to perform "in the post-traditional cosmopolitan world we live in".

"Religion" is especially interesting to 'recycle' in this way, for two reasons. One of them is that religion in the traditional cultures served for cultivating "human quality". If you believe, as Richard Dawkins does, that religion served that function poorly, that's just another reason to take up the challenge of 'recycling' "religion" by implementing this function in a completely new way.

The second reason is the etymology of "religion"—as "re" + "ligare", which suggests that "religion" is "re-connection". We may think of religion as connecting each of us to our purpose, and all of us into a society.

Religion is the alternative to selfishness.

Human systems are naturally self-organizing. We have seen that when selfishness or self-centeredness is what binds us to our purpose and to each other—then the power structure is the result.

We adapted the definition that Martin Lings contributed, and defined religion as "reconnection with the archetype" (which harmonizes with the etymological meaning of this word). We adapted Carl Jung's favorite keyword, and defined the archetype as whatever may be in our psychological makeup that may empower us to transcend selfishness. "Heroism", "justice", "motherhood", "freedom", "beauty", "truth" and "love" are obvious examples, but there are others.

Joseph Campbell's "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" is a classic about this theme, which showed that across geographical regions and historical periods, human cultures created myths to cultivate this important archetype, and reflect the dynamics of such cultivation. And then there are all others.

Imagine a world where truth, love, beauty, justice... are what binds us to our purpose, and to each other.

Isn't that what "a great cultural revival" is all about?

Books and publishing

Occasionally we publish books about of the above themes—to punctuate the laminar flow of events, draw attention to a theme and begin a dialog.

Shall we not recreate the book as well—along with all the rest? Yes and no. In "Amuzing Ourselves to Death", Neil Postman—who founded "media ecology"— left us a convincing argument why the book is here to stay. His point was that the book creates a different "ecology of the mind" than the contemporary "immersive" audio-visual media do; it gives us a chance to reflect.

We, however, embed the book exist in an 'ecosystem' of media. By publishing a book we 'break ice' and place a theme—which may or may not be one of our ten themes—into the focus of the public eye. We then let our collective mind digest and further develop the proposed ideas; and by doing that—develop itself!

In this way, a loop is closed through which an author's insights are improved by collective creativity and knowledge—leading, ultimately, to a new and better edition of the book.

Liberation

The book titled "Liberation", with subtitle "Religion beyond Belief", is scheduled to be completed during the first half of 2021, and serve as the first in the series.

In a fractal-like way, this book reflects the holotopia as a whole. We are accustomed to think of "religion" as a firm or dogmatic belief in something, impervious to counter-evidence. The Liberation book turns this idea of religion inside out—so that religion is understood as liberation from not only rigidly held beliefs, but from rigidly held anything.

The age-old conflict, between science and religion, is resolved by the book by further evolving both science and religion.

Prototypes

Prototypes, as we have seen, are a way to federate information by weaving it directly into the fabric of everyday reality. A prototype can be literally anything.

In the Holotopia prototype, everything is a prototype. In that way we subject everything to knowledge-based evolution.

The events are prototypes we have not yet talked abou. They are multimedia and multidimensional prototypes—which include a variety of more specific prototypes. Events are used to 'punctuate the equilibrium'—to create a discontinuity in the ordinary flow of events, draw attention to a theme, create a transformative space, both physical and in media, engage people and make a difference.

In what follows we illustrate this idea by describing the holotopia's Earth Sharing pilot event, which took place in June of 2018 in Bergen, Norway.

Vibeke Jensen, the artist who created what we are about to describe, is careful to avoid interpreting the space, the objects and the interaction she creates. The idea is to use them as prompts, and allow new meaning to emerge through association and group interaction. The interpretation we are about to give is by us others. It is, however, only a possible interpretation.

The physical space where the event took place was symbolic of the purpose of the event. The building used to be a bank in the old center of Bergen, and later became an art gallery. It remained to turn the gallery, holotopia-style, into a transformative space.

The space was upstairs—and Vibeke turned the stairs too into a symbolic object. Going up, the inscription on the stairs reads "bottom up"; going down, it reads "top down". In this way the very first thing that meets the eye is the all-important message, which defines the polyscopy and the holoscope—namely that we can reach insights in those two ways.

The BottomUp - TopDown intervention is a tool for shifting positions. It suggests transcendence of fixed relations between top and bottom, and builds awareness of the benefits of multiple points of view (polyscopy), and moving in-between.