Difference between revisions of "Holotopia: Power structure"

m |

m |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Power structure</em> devolution</h2></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Power structure</em> causes devolution</h2></div> |

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>Competition vs. collaboration</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Competition vs. collaboration</h3> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>But what <em>is</em> really the <em>power structure</em>? While our understanding will deepen gradually as we go along, what's we've just seen might already suggest that <em>power structures</em> are <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>, or "structures", that emerge when we compete instead of collaborating, and trust that "the invisible hand" of the "free market" will secure that the result is the best possible one.</p> |

| − | <p>On [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/CONVERSATIONS#ThePSposter The Paradigm Strategy Poster] (which was one of the forerunner <em>prototypes</em> to Holotopia) we used the [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/CONVERSATIONS#Chomsky-Harari-Graeber homsky–Harari–Graeber <em>thread</em>] to | + | <p>This popular <em>myth</em>, that <em>competition</em> (rather than informed co-creation) leads to the best possible world, appears to follow from Darwin's theory of evolution. Isn't that the way in which nature uses <em>her</em> creativity?</p> |

| + | <p>"Unfortunately, the evidence, such as it is, is against this simple-minded theory", wrote Norbert Wiener. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>On [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/CONVERSATIONS#ThePSposter The Paradigm Strategy Poster] (which was one of the forerunner <em>prototypes</em> to Holotopia) we used the [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/CONVERSATIONS#Chomsky-Harari-Graeber homsky–Harari–Graeber <em>thread</em>] to illustrate this point.</p> | ||

| + | <p>But what should we, really, have learned from Darwin? We preceded this <em>thread</em> by discussing Richard Dawkins' core insight, published in his 1976 book "The Selfish Gene". His point—which subsequently led to "memetics" as its application to cultural and societal evolution—was that the evolution must not be thought of as favoring utility or perfection of any kind, but <em>the fittest</em> or best adapted gene (or the fittest "meme", when it is cultural or social evolution we are talking about). </p> | ||

| − | <h3>The "fittest" | + | <h3>The "fittest" is not the best</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>So what does this mean, practically and concretely?</p> |

| − | + | <p>We answered this question by using the real-life history of "Alexander the Great" as a parable, as told by David Graeber, because it has all the elements we may want, to illustrate our points: The "fittest" system of its era (Alexander's army, with its corresponding "business model") was turning free people into slaves, destroying societies and cultures, homes, monasteries and palaces... and it <em>even</em> had "financial innovation" as one of its core elements!</p> | |

<p>The stories of Noam Chomsky and Noah Yuval Harari allow us to deepen our understanding of the dynamics that underlie the <em>power structure</em> devolution. We'll return to them when discussing the <em>socialized reality</em> insight.</p> | <p>The stories of Noam Chomsky and Noah Yuval Harari allow us to deepen our understanding of the dynamics that underlie the <em>power structure</em> devolution. We'll return to them when discussing the <em>socialized reality</em> insight.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>You may be working for a psychopath</h3> | ||

| + | <p>We supplemented a reflection on Joel Bakan's "the Corporation", to show that while today the most powerful <em>power structure</em> may <em>look</em> different than it did twenty-five centuries ago, its essential nature has remain unchanged.</p> | ||

| + | <p>As a law professor, Bakan explained how the modern corporation with time evolved to become the most powerful institution on the planet. And how—through a few centuries of legal maneuvering—it acquired the legal status of a person, but without the corresponding accountability. So Bakan asked—if the corporation is a person, <em>what sort of person</em> is it? In his documentary, and the corresponding book, Bakan showed that the corporation has all the characteristics that qualify a psychopath. </p> | ||

| + | |||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Power structure</em> is us</h2></div> |

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>The enemy is us</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The enemy is us</h3> | ||

| − | <p>"We have seen the enemy, and he is us" said famously Pogo, Walt Kelly's cartoon hero. A funny | + | <p>"We have seen the enemy, and he is us" said famously Pogo, Walt Kelly's cartoon hero. A funny idea for a cartoon; <em>but could it be real</em>?</p> |

<h3>Cruelty has been modernized</h3> | <h3>Cruelty has been modernized</h3> | ||

| Line 72: | Line 78: | ||

<p>Perhaps the most daring of Zygmunt Bauman's aring ideas is that even the concentration camps were only extreme cases of cruelty that resulted in this way.</p> | <p>Perhaps the most daring of Zygmunt Bauman's aring ideas is that even the concentration camps were only extreme cases of cruelty that resulted in this way.</p> | ||

| − | <h3> | + | <!-- XXX |

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Bauman has not yet been heard</h3> | ||

<p>The movie "The Reader" allows us to extend Bauman's observations. And indeed in several most interesting ways.</p> | <p>The movie "The Reader" allows us to extend Bauman's observations. And indeed in several most interesting ways.</p> | ||

<p>By telling the story of a woman who, as a concentration camp guard, was part of an unthinkable cruelty because she was "only doing her job", and because "otherwise there would be chaos", the movie gives a vivid confirmation of Bauman's ideas. </p> | <p>By telling the story of a woman who, as a concentration camp guard, was part of an unthinkable cruelty because she was "only doing her job", and because "otherwise there would be chaos", the movie gives a vivid confirmation of Bauman's ideas. </p> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 88: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Systemic innovation</em> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2><em>Systemic innovation</em> is the key to solution</h2></div> |

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>Erich Jantsch's insight</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>Erich Jantsch's insight</h3> | ||

<p>Having delivered the opening keynote at the inaugural meeting of The Club of Rome, Erich Jantsch clearly saw what needed to be done, if the "problematique" was to be resolved (see it outlined [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/STORIES#Jantsch here] and [https://holoscope.info/2019/11/14/knowledge-federation-in-a-nutshell/#Jantsch here]).</p> | <p>Having delivered the opening keynote at the inaugural meeting of The Club of Rome, Erich Jantsch clearly saw what needed to be done, if the "problematique" was to be resolved (see it outlined [http://kf.wikiwiki.ifi.uio.no/STORIES#Jantsch here] and [https://holoscope.info/2019/11/14/knowledge-federation-in-a-nutshell/#Jantsch here]).</p> | ||

Revision as of 14:21, 24 June 2020

Contents

H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

Power structure

Powered by ingenuity of innovation, the Industrial Revolution revolutionized the efficiency of human work. Where could the next revolution of this kind be coming from?

We look at the systems in which we live and work. Imagine them as gigantic machines, comprising people and technology. Their function is to take people's daily work as input, and turn it into socially useful effects. If our work has become incomparably more efficient and yet we've remained busy—should we not see whether they might be wasting our time? And if our best efforts result in problems rather than solutions—should we not check whether they might be causing those problems?

Stories

Power structure wastes resources

A costly oversight

While the ingenuity of our innovation has been focused on small gadgets we can hold in our hand—those 'gigantic machines' constitute a proportionally more important, and yet overlooked creative frontier. How much is this oversight costing us?

On Page 4 of the article The Game-Changing Game–A Practical Way to Craft the Future we answered this question by giving a summary of our Ferguson–McCandless–Fuller thread, of which we here highlight the main points.

As always, our stories are intended to illustrate rather than rigorously prove the proposed views.

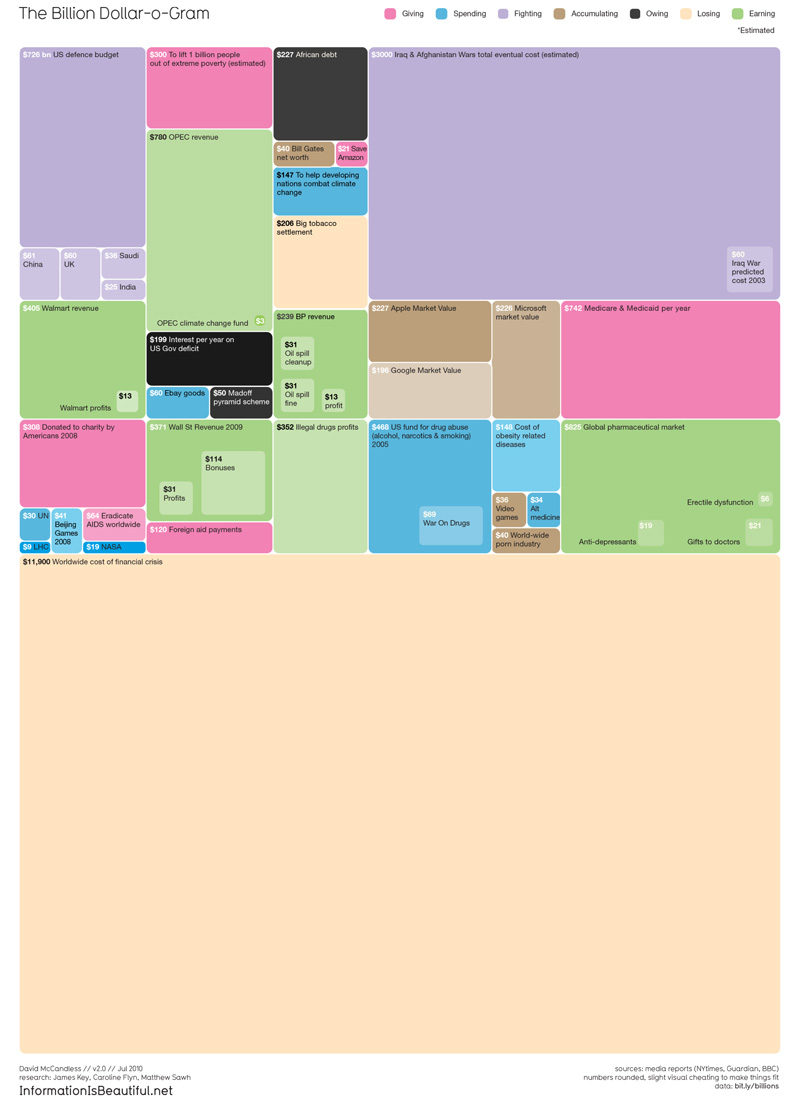

David McCandless: The Billion-Dollar-o-Gram 2009

A quick look at David McCandless' Billion-Dollar-o-Gram 2009 will show that the costs of two issues ("Worldwide cost of financial crisis" and "Iraq & Afganistan wars total eventual cost") dominate the image so dramatically, that the costs of issues ("to lift one billion people out of extreme poverty", "African debt", "save the amazon"...) seem insignificant in comparison.

The largest costs are systemically caused

We tell the story of Charles Ferguson's two award-winning documentaries to highlight—as he did in his films—that those two issues were systemically caused. Or in other words that they were "inside jobs", as the title of Ferguson's second film suggested.

Fuller may have been right

In the late 1960s, Buckminster Fuller predicted that by the end of the century science and technology would have advanced enough to enable us, the people on the planet, to put an end to scarcity. And that our core challenge would be to reconfigure the use and distribution of those resources—which now sapped through scarcity-based competition.

What we have just seen suggests that Fuller may have been right.

In 1969 Fuller proposed to the American Senate a computer-based solution called the World Game. Its whose purpose was to enable the global policy makers to see the world as one, and collaborate on allocating and sharing its resources, instead of competing.

Power structure causes devolution

Competition vs. collaboration

But what is really the power structure? While our understanding will deepen gradually as we go along, what's we've just seen might already suggest that power structures are the systems in which we live and work, or "structures", that emerge when we compete instead of collaborating, and trust that "the invisible hand" of the "free market" will secure that the result is the best possible one.

This popular myth, that competition (rather than informed co-creation) leads to the best possible world, appears to follow from Darwin's theory of evolution. Isn't that the way in which nature uses her creativity?

"Unfortunately, the evidence, such as it is, is against this simple-minded theory", wrote Norbert Wiener.

On The Paradigm Strategy Poster (which was one of the forerunner prototypes to Holotopia) we used the homsky–Harari–Graeber thread to illustrate this point.

But what should we, really, have learned from Darwin? We preceded this thread by discussing Richard Dawkins' core insight, published in his 1976 book "The Selfish Gene". His point—which subsequently led to "memetics" as its application to cultural and societal evolution—was that the evolution must not be thought of as favoring utility or perfection of any kind, but the fittest or best adapted gene (or the fittest "meme", when it is cultural or social evolution we are talking about).

The "fittest" is not the best

So what does this mean, practically and concretely?

We answered this question by using the real-life history of "Alexander the Great" as a parable, as told by David Graeber, because it has all the elements we may want, to illustrate our points: The "fittest" system of its era (Alexander's army, with its corresponding "business model") was turning free people into slaves, destroying societies and cultures, homes, monasteries and palaces... and it even had "financial innovation" as one of its core elements!

The stories of Noam Chomsky and Noah Yuval Harari allow us to deepen our understanding of the dynamics that underlie the power structure devolution. We'll return to them when discussing the socialized reality insight.

You may be working for a psychopath

We supplemented a reflection on Joel Bakan's "the Corporation", to show that while today the most powerful power structure may look different than it did twenty-five centuries ago, its essential nature has remain unchanged.

As a law professor, Bakan explained how the modern corporation with time evolved to become the most powerful institution on the planet. And how—through a few centuries of legal maneuvering—it acquired the legal status of a person, but without the corresponding accountability. So Bakan asked—if the corporation is a person, what sort of person is it? In his documentary, and the corresponding book, Bakan showed that the corporation has all the characteristics that qualify a psychopath.

Power structure is us

The enemy is us

"We have seen the enemy, and he is us" said famously Pogo, Walt Kelly's cartoon hero. A funny idea for a cartoon; but could it be real?

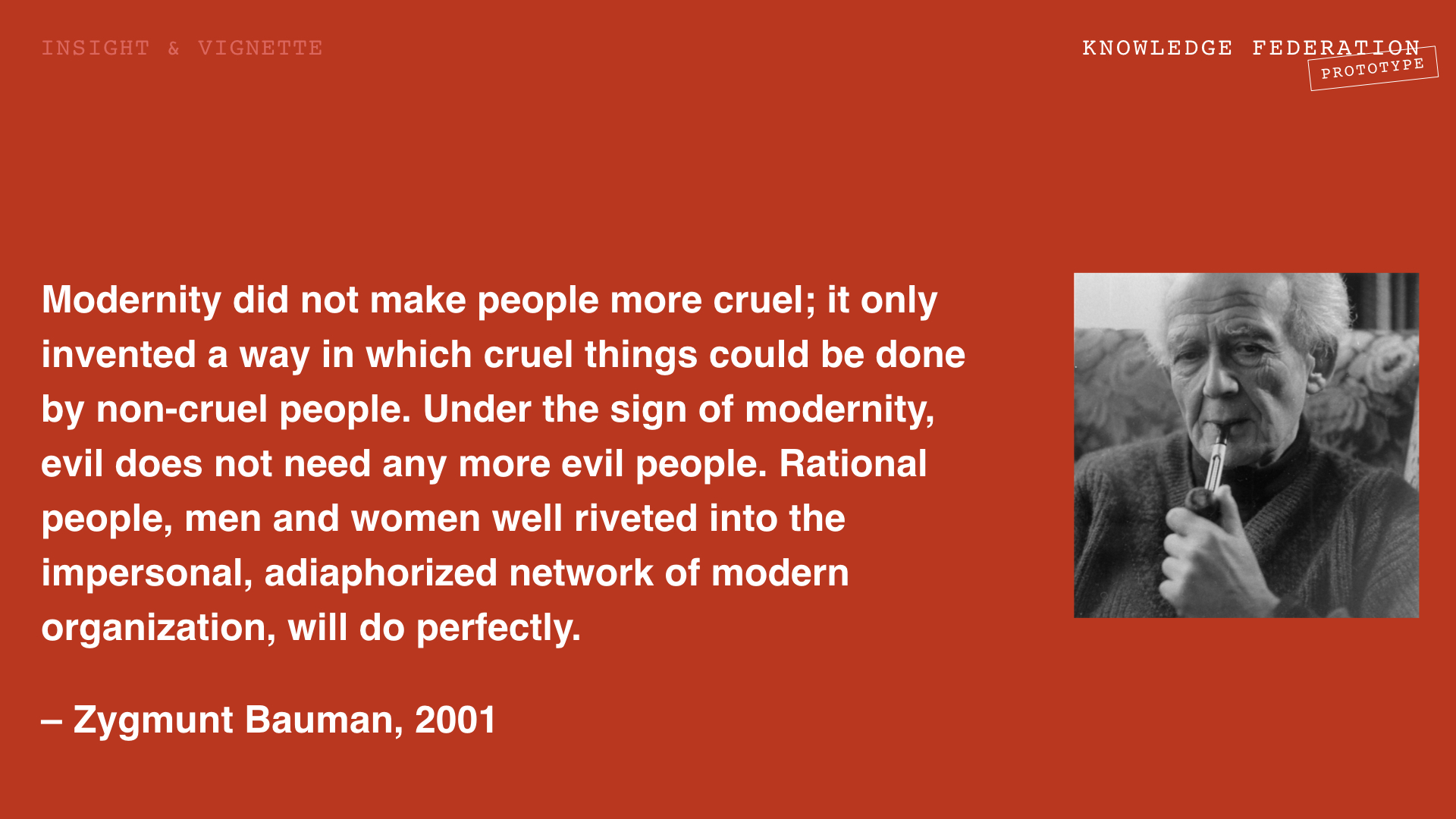

Cruelty has been modernized

The cruelty in modernity has changed its form, observed Bauman. It no longer requires cruel people; "normal" people, "doing their jobs"—within the structure of a modern organization, will do just fine.

Perhaps the most daring of Zygmunt Bauman's aring ideas is that even the concentration camps were only extreme cases of cruelty that resulted in this way.