Difference between revisions of "Holotopia: Convenience paradox"

m |

m |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>The paradox of happiness</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The Buddha</h3> | ||

| + | <p>A prince in India takes a stroll through the village, and remains shocked by seeing people suffer. He decides to leave the shelter of his palace and family, and to withdraw into the forest and search the way out of suffering.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Having tried several approaches to <em>human development</em> and nearly died trying, Siddartha sat for five years meditating under the Bo Tree, and by achieving complete enlightenment found reached also the goal of his quest. Returning to the world, his first sermon was about "The Four Noble Truths", of which the first was the truth of "suffering".</p> | ||

| + | <p>This, of course, is a legend; do you find it plausible?</p> | ||

| + | <p>We don't. We find it difficult to imagine that even a prince could be so sheltered as to be surprised to see suffering; and that an enlightened being could talk about the truth of suffering as his great realization, and gift to the world.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Everything changes, however, when we replace the word "suffering" by the original Pali keyword "dukkha". But what <em>is</em> "dukkha"?</p> | ||

| + | <p>Well, that's exactly what the First Noble Truth of Buddhism is about!</p> | ||

| + | <p>To a future conversation where we shall explore and deepen this theme, we offer the following two points: | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Our everyday emotional life is by and large just <em>dukkha</em>, just "suffering" that the Buddha undertook to eliminate</li> | ||

| + | <li>The Way he found and taught was not only different—it was <em>opposite</em> from the way in which we tend to "pursue happiness" today</li> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>The Christ</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The following excerpt from Christ's teaching will serve to illustrate The Buddha's Way, and at the same time suggest that it is not in essence different from what other great humanity's teachers taught.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Matthew 6:26 in the New Testament reads: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | See the birds of the sky, that they don’t sow, neither | ||

| + | do they reap, nor gather into barns. Your heavenly Father | ||

| + | feeds them. Aren’t you of much more value than they? | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | <p>The point is, of course, <em>not</em> to avoid work—but to work as an act of service, and without "reaching out" for the fruit. Just as the Buddha, and so many other teachers of the Way—not excluding Moshe Feldenkrais—taught. </p> | ||

| + | <p>The result is well beyond the cessation of suffering. Here is how C. F. Andrews described it in "The Sermon on the Mount". | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | (The disciples of Christ) found in this new new 'Way of Life' such a superabundance of joy, even in the midst of suffering, that they could hardly contain it. Their radiance was unmistakable. When the Jewish rulers saw their boldness, they "marvelled and took knowledge of them that they had been with Jesus" (Acts 4. 13). | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

| + | </div> </div> | ||

<!-- XXX | <!-- XXX | ||

Revision as of 09:04, 8 June 2020

Contents

H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

Convenience paradox

The Renaissance liberated our ancestors from preoccupation with the afterlife, and empowered them to seek happiness here and now. The lifestyle changed, and the culture blossomed. How could the next such change begin?

Without suitable information to show us the way, we pursue convenience—what brings immediate gratification.

But convenience is a deceptive value, which surprisingly often leads to a less convenient condition.

In its shadow, there are a wealth of insights and opportunities that we can use to vastly improve our condition; through "human development", and "cultural revival".

Stories

In the shadow of our cherished value—of instant gratification or convenience—reside a wealth of ignored opportunities for improving our condition through human development. When they've become known, the "great cultural revival" will most naturally follow.

The way and the paradox

Lao-Tzu

According to tradition, Lao-Tzu or "Old Master", an ancient wise man of China, was on his way out of China to end his life in solitary contemplation. But the border guard would not let him leave, until he wrote down the essence of his wisdom for posterity.

We let the Old Master convey to us two insights:

- Instead of reaching out for the objects of our desire, must focus on our way of life—and harmonize it with the overarching Way of the universe

- The Way (called Tao) to the highest good is hidden from us by a paradox

We let the following excerpt from Tao-Te Ching, the book of wisdom that the Old Master's allegedly left to the border guard, summarize his message for us.

That the weak can defeat the strong—

There is no one in the whole world who doesn't know it,

And yet there is no one who can put it into practice.

The paradox of physical effort

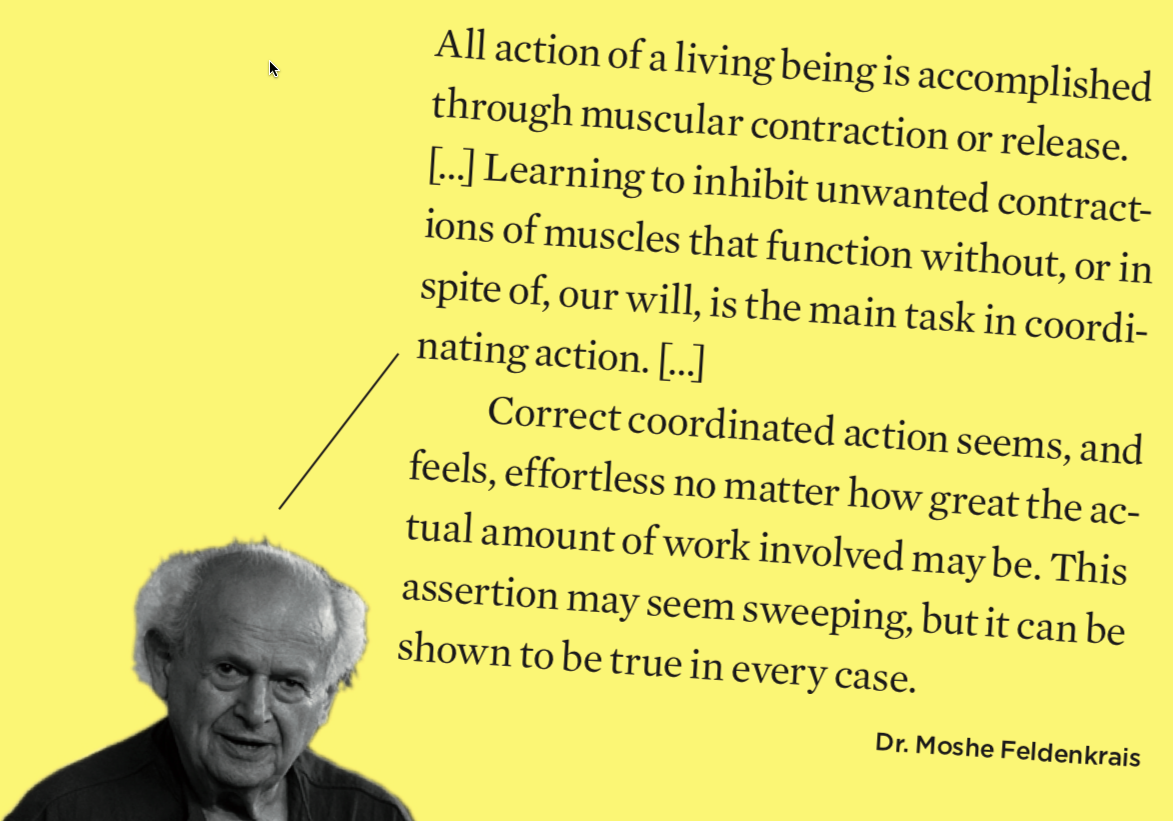

Moshe Feldenkrais

The heaviest thing we ever lift up and carry is the one we can never get rid of—our body.

We let Moshe Feldenkrais too appear here ideographically, to point to the physical side of the convenience paradox:

We build the technology to make life easy; but the lion's share of our effort is in the way in which we use ourselves—which can only be improved through human development.

The paradox of happiness

The Buddha

A prince in India takes a stroll through the village, and remains shocked by seeing people suffer. He decides to leave the shelter of his palace and family, and to withdraw into the forest and search the way out of suffering.

Having tried several approaches to human development and nearly died trying, Siddartha sat for five years meditating under the Bo Tree, and by achieving complete enlightenment found reached also the goal of his quest. Returning to the world, his first sermon was about "The Four Noble Truths", of which the first was the truth of "suffering".

This, of course, is a legend; do you find it plausible?

We don't. We find it difficult to imagine that even a prince could be so sheltered as to be surprised to see suffering; and that an enlightened being could talk about the truth of suffering as his great realization, and gift to the world.

Everything changes, however, when we replace the word "suffering" by the original Pali keyword "dukkha". But what is "dukkha"?

Well, that's exactly what the First Noble Truth of Buddhism is about!

To a future conversation where we shall explore and deepen this theme, we offer the following two points:

- Our everyday emotional life is by and large just dukkha, just "suffering" that the Buddha undertook to eliminate

- The Way he found and taught was not only different—it was opposite from the way in which we tend to "pursue happiness" today

</p>

The Christ

<p>The following excerpt from Christ's teaching will serve to illustrate The Buddha's Way, and at the same time suggest that it is not in essence different from what other great humanity's teachers taught.</p> <p>Matthew 6:26 in the New Testament reads:

See the birds of the sky, that they don’t sow, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns. Your heavenly Father feeds them. Aren’t you of much more value than they?

</p> <p>The point is, of course, not to avoid work—but to work as an act of service, and without "reaching out" for the fruit. Just as the Buddha, and so many other teachers of the Way—not excluding Moshe Feldenkrais—taught. </p> <p>The result is well beyond the cessation of suffering. Here is how C. F. Andrews described it in "The Sermon on the Mount".

(The disciples of Christ) found in this new new 'Way of Life' such a superabundance of joy, even in the midst of suffering, that they could hardly contain it. Their radiance was unmistakable. When the Jewish rulers saw their boldness, they "marvelled and took knowledge of them that they had been with Jesus" (Acts 4. 13).

</p> </div> </div>