Holotopia

Contents

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

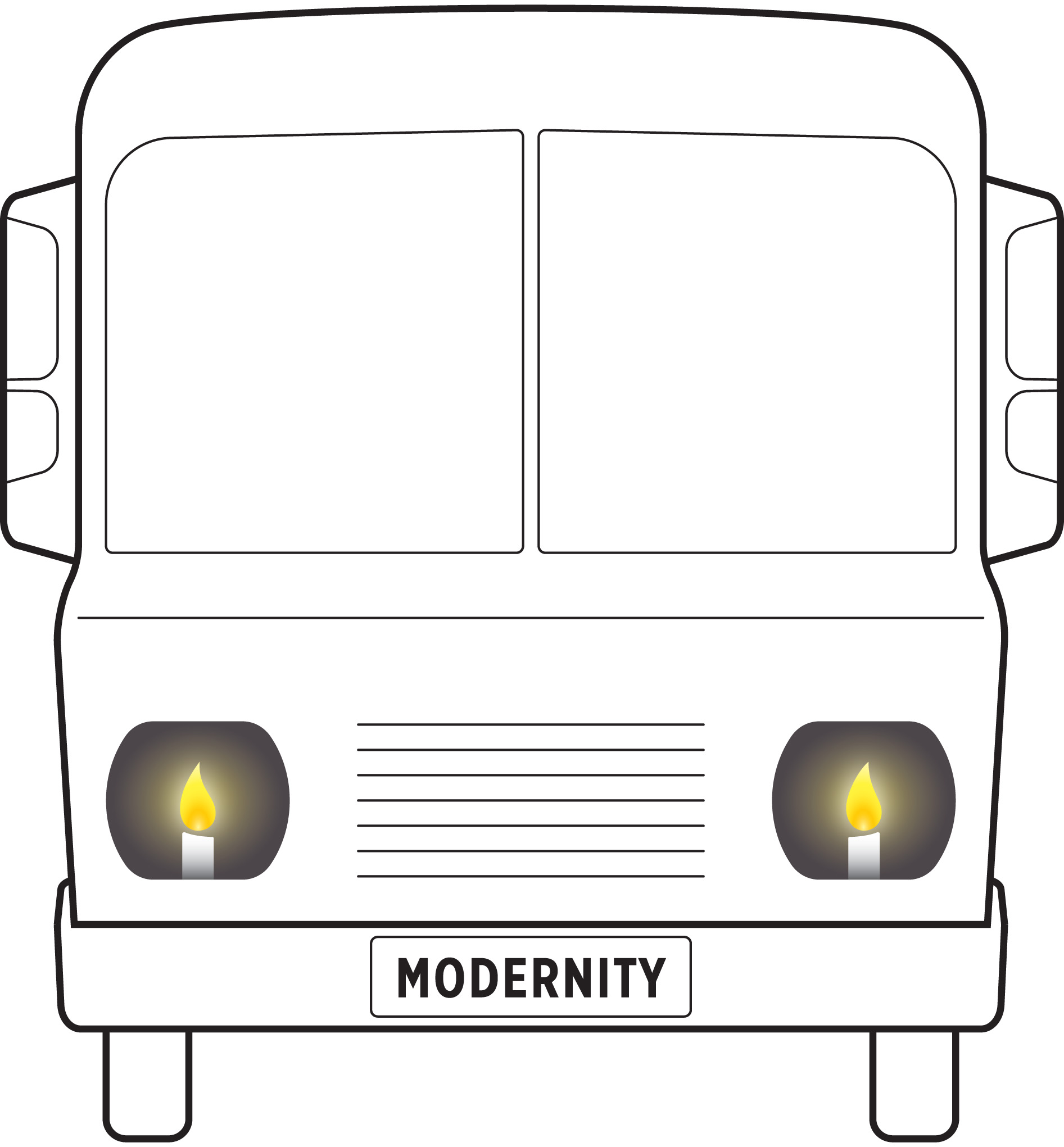

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Scope

We have just seen, by highlighting the historicity of the academic approach to knowledge to reach the socialized reality insight, that the academic tradition—now instituted as the modern university—finds itself in a much larger and more central social role than it was originally conceived for. We look up to the academia (and not to the Church and the tradition) to tell us how to look at the world, to be able to comprehend it and handle it.

That role, and question, carry an immense power!

It was by providing a completely new answer to that question, that the last "great cultural revival" came about.

Could a similar advent be in store for us today?

Diagnosis

How should we look at the world, to be able to comprehend it and handle it?

Nobody knows!

Of course, countess books and articles have been written about this theme since antiquity. But in spite of that—or should we rather say because of that—no consensus has been reached.

Meanwhile, the way we the people look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it, shaped itself spontaneously—from the scraps of the scientific ideas that were available around the middle of the 19th century, when Darwin and Newton as cultural heroes replaced Adam and Moses. What is today popularly considered as the "scientific" worldview shaped itself then—and remained largely unchanged.

As members of the homo sapiens species, this worldview makes us believe, we have the evolutionary privilege to be able to comprehend the world in causal terms, and to make rational choices based on such comprehension. Give us a correct model of the natural world, and we'll know exactly how to go about satisfying our needs (which we of course know, because we can experience them directly). But the traditional cultures, being unable to understand how the nature works, put a "ghost in the machine"—and made us pray to him to give us what we needed. Science corrected this error—and now we can satisfy our needs by manipulating the nature directly and correctly, with the help of technology.

It is this causal or "scientific" understanding of the world that makes us modern. Isn't that how we understood that women cannot fly on broomsticks?

From our collection of reasons why this way of looking at the world is neither scientific nor functional, we here mention two.

The first is that the nature is not a "machine".

The mechanistic or "classical" way of looking at the world that Newton and his colleagues developed in physics, which around the 19th century shaped the worldview of the masses, has been disproved and disowned by modern science. It has turned out that even physical phenomena exhibit the kinds of interdependence that cannot be understood in that way.

In "Physics and Philosophy", Werner Heisenberg, one of the progenitors of this research, described how "the narrow and rigid frame" as the way of looking at the world that our ancestors concocted from the 19th century science was damaging to culture, and in particular to religion and ethical norms on which the "human quality" depended. And how the prominence of "instrumental" thinking and values resulted, which Bauman called "adiaphorisation". Heisenberg explained how the modern physics disproved that worldview. Heisenberg expected that the largest impact of modern physics would be on culture—by allowing it to evolve further, by dissolving the narrow frame.

In 2005, Hans-Peter Dürr (considered in Germany as Heisenberg's intellectual and scientific "heir") co-wrote the Potsdam Manifesto, whose title and message is "We need to learn to think in a new way". The proposed new thinking is conspicuously similar to the one that leads to holotopia: "The materialistic-mechanistic worldview of classical physics, with its rigid ideas and reductive way of thinking, became the supposedly scientifically legitimated ideology for vast areas of scientific and political-strategic thinking. (...) We need to reach a fundamentally new way of thinking and a more comprehensive understanding of our Wirklichkeit (world, or reality), in which we, too, see ourselves as a thread in the fabric of life, without sacrificing anything of our special human qualities. This makes it possible to recognize humanity in fundamental commonality with the rest of nature (...)"

The second reason is that even complex "machines" ("classical" nonlinear dynamic systems) cannot be understood in causal terms.

It has been observed that the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. Research in systems sciences, and in particular in cybernetics, has explained that curious phenomenon in a scientific way: The "hell" (which you may imagine as global issues, or the 'destination' toward which our 'bus' is diagnosed to be headed) is largely a result of various "side effects" of our best efforts and "solutions", resulting from "nonlinearities" and "feedback loops" in natural and social systems we are trying to govern.

Hear Mary Catherine Bateson (cultural anthropologist and cybernetician, and the daughter of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson who pioneered both fields) say:

"The problem with Cybernetics is that it is not an academic discipline that belongs in a department. It is an attempt to correct an erroneous way of looking at the world, and at knowledge in general. (...) Universities do not have departments of epistemological therapy!"

Remedy

The remedy we offered builds upon the foundation we proposed related to the socialized reality insight.

We showed how truth by convention allows us to explicitly define a way to look at the world, which allows us to truly comprehend it and handle it.

We called the result a general-purpose methodology; we called our prototype the Polyscopic Modeling methodology or polyscopy.

A methodology is in essence a toolkit; any sort of rules could do, as long as they give us the insights we need. We, however, defined polyscopy by turning the core findings in 20th century science into conventions. (While a thorough federation was conducted, Einstein's "Autobiographical Notes" alone were sufficient for our purpose.) In this way we repaired the severed link between information and action also in this fundamental domain, where scientific findings meet the popular worldview.

The holotopia prototype is conceived as a way to federate this new thinking further.

allows us to is to spell out the rules, by defining a general-purpose methodology as a convention; and by turning it into a prototype and developing it continuously—to remain consistent with the state of the art of relevant knowledge, technology, and our society's needs.</p>

Our prototype is called Polyscopic Modeling methodology, and nicknamed polyscopy.

By defining a methodology, we can define an approach to knowledge.

Polyscopy, for instance, specifies that for "knowledge" to be real knowledge, information must be federated. This means that we must abolish the habit of throwing out whatever fails to fit our "scientific worldview", or socialized reality or narrow frame. "Knowledge" maintained by ignoring counter-evidence does not merit that name.

This does not mean, of course, that anything goes. Rather, it demands a praxis that may be understood by analogy with constitutional democracy—in the realm of ideas. As even a hateful criminal has the right for a fair trial, so does an idea have the right to be considered. Based on this simple rule of thumb, we would, for instance, be advised to not ignore Buddhism because we don't find it appealing, or because we don't believe in reincarnation. The work of knowledge federation is here similar to the work of a dutiful attorney—it is to carefully sift through the heritage, find pieces that we may need to integrate; and support them with a convincing case.

Knowledge federation turns insights and data into principles and rules of thumb, which help us orient action. Especially valuable are the ones we call gestalts. A gestalt is an interpretation of a situation that suggests suitable action. "Our house is on fire" is a canonical example. This keyword allows us to define the intuitive notion "informed"—as having a gestalt that is appropriate to one's situation. You will easily recognize now that we'll be using this idea all along, by rendering our general situation as the Modernity ideogram, and our academic one as the Mirror ideogram. And that we are making headway toward a third—the holotopia vision. Suitable techniques for communicating and 'proving' or justifying such claims are offered, most of which are developed by generalizing the standard toolkit of science.

A parabolic image will help us see some practical consequences of this approach. Imagine you are talking on the phone with your neighbor, that he's at work and you are at home, and that you see that his house is on fire. Yet you tell him about the sale in the neighborhood fishing gear store. While from a factual point of view nothing is wrong (your neighbor is an avid fisherman, and the sale you are telling him about will deeply interested him), in this new "reality" we are proposing you are being untruthful and dangerously deceptive, because a wrong gestalt is implicit in the "reality picture" you present. You will easily see how this reflects upon our conventional media informing, and the way in which it constructs the "reality" we are living in.

The Polyscopic Modeling methodology is defined as a convention. We could turn anything into a convention—and it would be fine as long as it serves the purpose; as long as it "works". We, however, chose to federate this methodology, and turn it into a prototype.

This gives us a way to make the idea of "right" information this methodology represents a function of relevant insights reached in the sciences; and to allow it to evolve.

To illustrate this approach, and to point at some further nuances that are worth highlighting, we now describe a single instance of a source that has been federated in this way—and to give due credit.

A situation with overtones of a crisis, closely similar to the one we now have in our handling of information at large, arose in the early days of computer programming, when the buddying industry undertook ambitious software projects—which resulted in thousands of lines of "spaghetti code", which nobody was able to understand and correct. The story is interesting, but here we only highlight the a couple of main points and lessons learned.

They are drawn from the "object oriented methodology", developed in the 1960s by Old-Johan Dahl and Krysten Nygaard. The first one is that—to understand a complex system—abstraction must be used. We must be able to create concepts on distinct levels of generality, representing also distinct angles of looking (which, you'll recall, we called aspects). But that is exactly the core point of polyscopy, suggested by the methodology's very name.

The second point we'd like to highlight is is the accountability for the method. Any sufficiently complete programming language including the native "machine language" of the computer will allow the programmers to create any sort of program. The creators of the "programming methodologies", however, took it upon themselves to provide the programmers the kind of programming tools that would not only enable them, but even compel them to write comprehensible, reusable, well-structured code. To see how this reflects upon our theme at hand, our proposal to add systemic self-organization to the academia's repertoire of capabilities, imagine that an unusually gifted young man has entered the academia; to make the story concrete, let's call him Pierre Bourdieu. Young Bourdieu will spend a lifetime using the toolkit the academia has given him. Imagine if what he produces, along with countless other selected creative people, is equivalent to "spaghetti code" in computer programming! Imagine the level of improvement that this is pointing to!

The object oriented methodology provided a template called "object"—which "hides implementation and exports function". What this means is that an object can be "plugged into" more general objects based on the functions it produces—without inspecting the details of its code! (But those details are made available for inspection; and of course also for continuous improvement.)

The solution for structuring information we provided in polyscopy, called information holon, is closely similar. Information, represented in the Information ideogram as an "i", is depicted as a circle on top of a square. The circle represents the point of it all (such as "the cup is whole"); the square represents the details, the side views.

When the circle is a gestalt, it allows this to be integrated or "exported" as a "fact" into higher-level insights; and it allows various and heterogeneous insights on which it is based to remain 'hidden', but available for inspection, in the square. When the circle is a prototype it allows the multiplicity of insights that comprise the square to have a direct systemic impact, or agency.

The prototype polyscopic book manuscript titled "Information Must Be Designed" book manuscript is structured as an information holon. Here the claim made in the title (which is the same we made in the opening of this presentation by talking about the bus with candle headlights) is justified in four chapters of the book—each of which presents a specific angle of looking at it.

It is customary in computer methodology design to propose a programming language that implements the methodology—and to bootstrap the approach by creating a compiler for that language in the language itself. In this book we did something similar. The book's four chapters present four angles of looking at the general issue of information, identify anomalies and propose remedies—which are the design patterns of the proposed methodology. The book then uses the methodology to justify the claim that motivates it—that makes a case for the proposed paradigm, by using the paradigm.