Holotopia

Contents

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

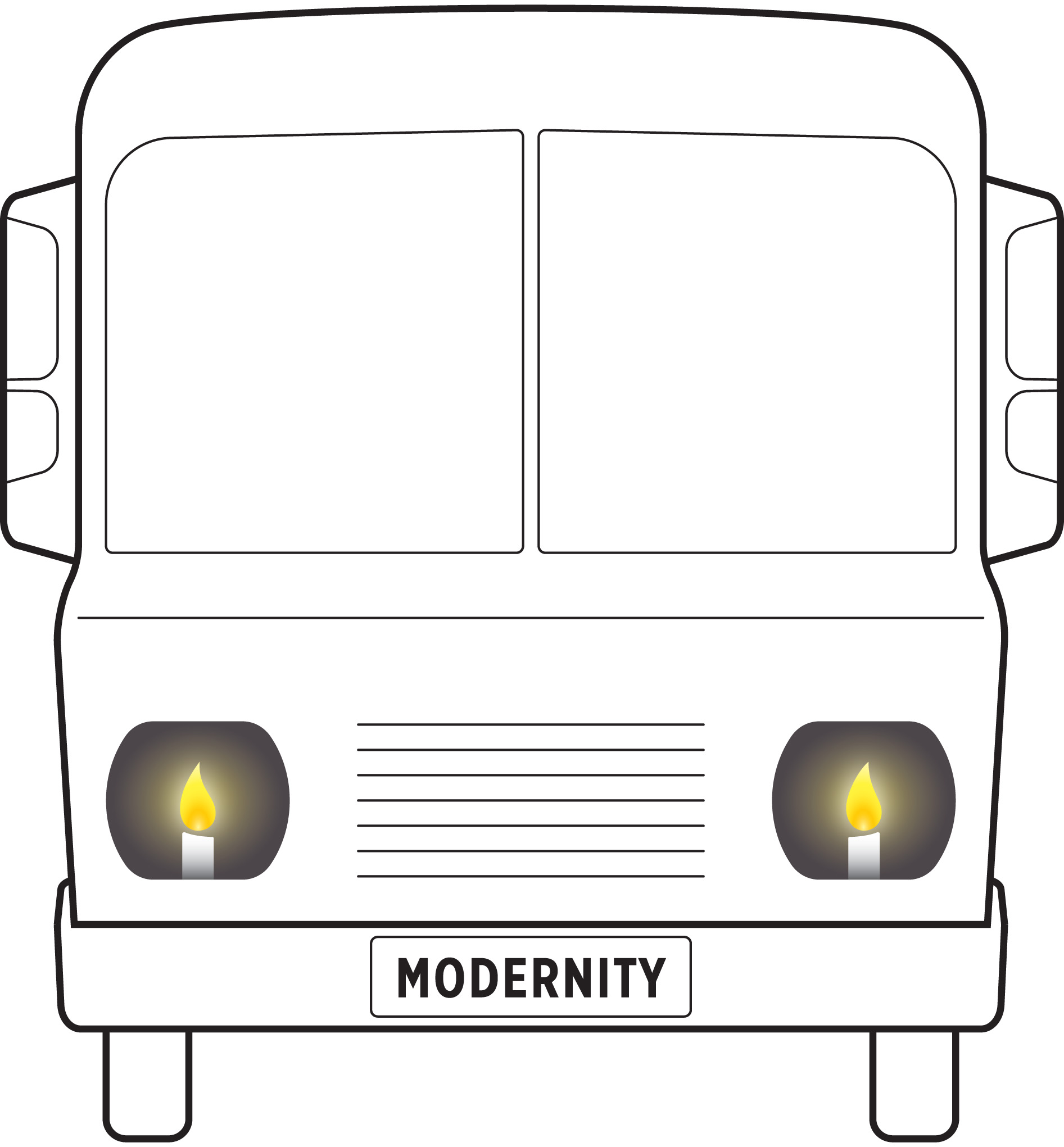

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Our proposal

The core of our knowledge federation proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of knowledge federation, by which those and other related questions are answered.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field, and a real-life praxis (informed practice)—and by doing that restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

A proof of concept application

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to change course:

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century's thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

Can the change of 'headlights' we are proposing enable us to "change course"?

A vision

Holotopia is the vision of a possible future that results when proper light has been turned on.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. But in view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" emerged as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It is a more attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the holotopia is readily realizable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights, as explained below.

A principle

What do we need to do to change course toward the holotopia?

From a collection of insights from which the holotopia emerges as a future worth aiming for, we have distilled a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by the holotopia's very name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

A method

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To make things whole—we must be able to see them whole!

To highlight that the knowledge federation methodology described and implemented in the proposed prototype affords that very capability, to see things whole, in the context of the holotopia we refer to it by the pseudonym holoscope.

While characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

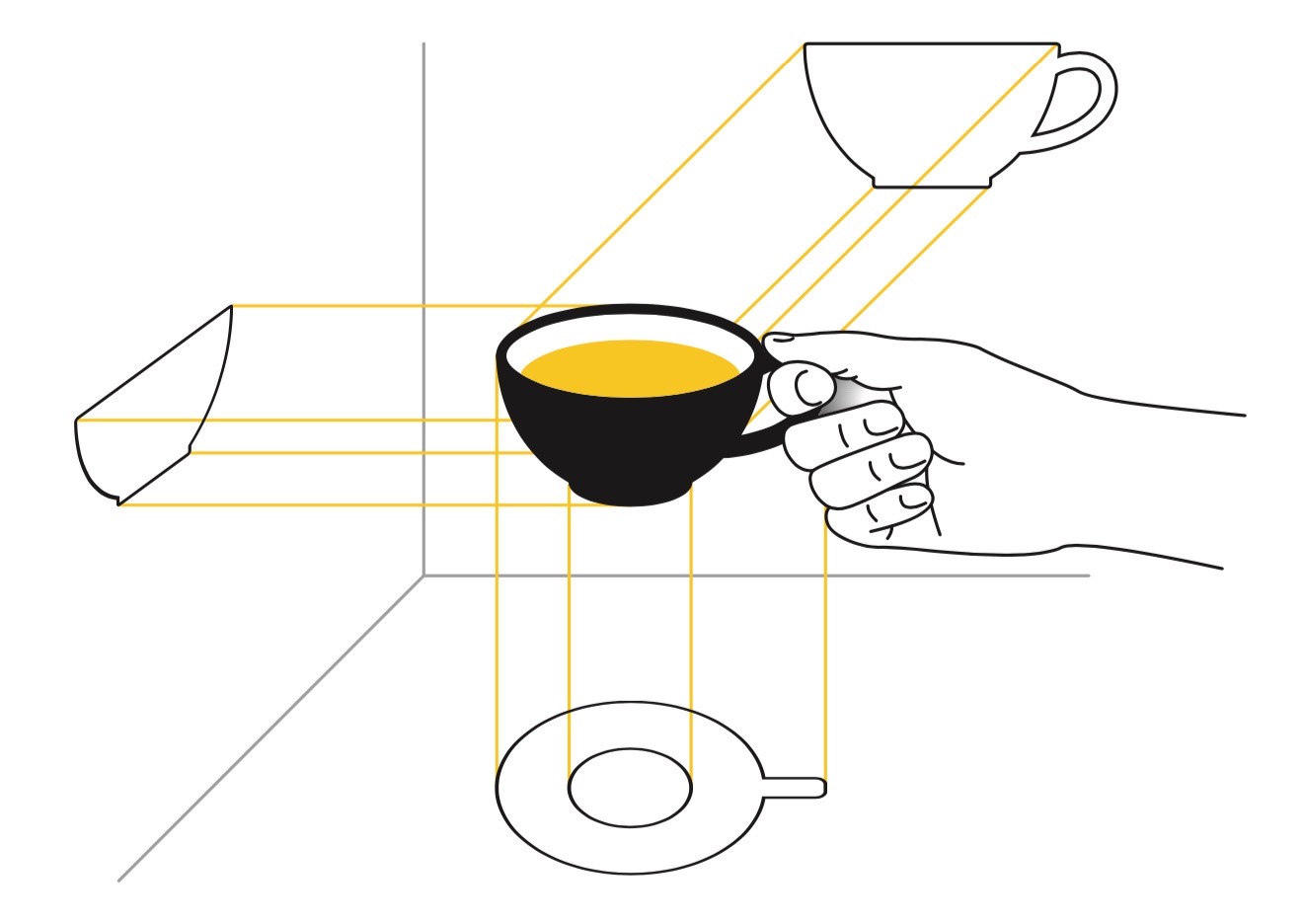

To see things whole, we must look at all sides.

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for a deliberate creation and choice of multiple ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. This conscious, free and informed choice of the ways in which we look at the world (as a more "moder" alternative to adhering to the habitual, inherited, reified or traditional ways) is the defining characteristic of the holoscope. The goal is to be able to 'see from all sides', and condense a volume of data to a simple insight that points to correct action ('the cup is whole', or 'the cup has a crack').

It is important to bear in mind that the resulting views are not offered as "reality pictures" contending for the "reality" status with one another and with our conventional ones—but as simplifications similar to projections in technical drawing. We shall continue to use the conventional language and say that X is Y—although it would be more correct to say that X can or must (also) be seen as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way; and to do that collaboratively, in a dialog.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

To see what we do not see, we take advantage of the insights of others. The holoscope combines scientific and other insights to provide us the vision we need. By deliberately choosing scopes, and taking advantage of this distinguishing feature of the holoscope, we can discover structural defects ('cracks') in some of the core constituting elements of our society or culture, which—when seen in our habitual ways (or metaphorically 'in the light of the candle')—tend to appear to us as just normal.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a cardboard map of a city, and a construction site. By sharing them, we are not making a case for that specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life praxis.

Five insights

Scope

Consider the huge momentum with which our civilization is rushing onward.

What new discovery, what technical invention might have a sufficiently large potential impact, to even have a chance to qualify as "a way to change course"?

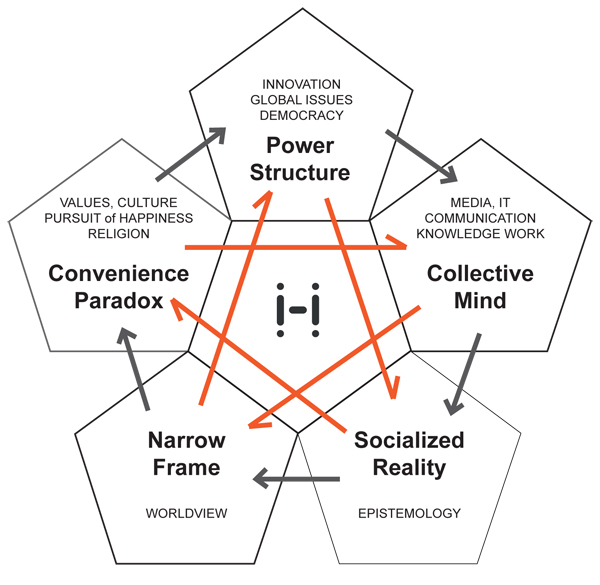

In what follows we use the holoscope as a technical invention, to look at five pivotal domains, which determine the "course":

- Innovation—the way we use our ability to create, and induce change

- Communication—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is created and used

- Epistemology—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning, which determine "the relationship we have with information"

- Method—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life, which determines "the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it"

- Values, or how we "pursue happiness"—which in a free society directly determine the course

In each of them, by using the holoscope to combine existing research results into an insight, we discover a structural defect, which has led to perceived problems; including those problems that now demand that we "change course".

In each of the cases, we find, also by combining published insights, a basic principle or a rule of thumb that has been ignored and violated—which led to the structural defect.

In each of the cases, we see how the structural defect can be remedied by using the corresponding principle; and that this scientific approach to problems (where we don't merely treat symptoms, but use develop and use knowledge to see and handle its physiological and anatomical causes) leads to improvements that are well beyond mere removal of symptoms.

The holotopia vision results.

A sixth insight then follows—that we already own all the information needed to take care of our problems. And that our basic problem is that we don't use it—because "the tie between information and action has been severed". And hence that the key to solution, the "systemic leverage point" for "changing course" and continuing to evolve culturally and socially, in a new way, is the same as it was in Galilei's time—we must "change the relationship we have with information"

A case for our proposal will then also be made

Since the mentioned leverage point, the relationship we have with information, is no longer controlled by the Church but by the academia—this task of changing it will require no more than to continue an age-old process, the evolution of the academic tradition, a step forward.

In the spirit of the holoscope, we here only summarize each of the five insights—and provide evidence and details separately.

Scope

"Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it", observed Peccei.

We look at the way in which man uses his power to innovate (create, and induce change).

We readily observe that we use competition or "survival of the fittest" to orient innovation and choose the way; not information, not "making things whole". The popular belief that "free competition" on the "free market" of goods, ideas and policies will serve us best also makes our democracies elect the leaders who represent that view. But is that belief warranted?

Genuine revolutions bring new ways to see freedom and power; holotopia is no exception.

We offer this keyword, power structure, as a means to that end. Think of the power structure as a new way to conceive of the intuitive notion "power holder"—an entity that might take away our freedom; or harm us and be our "enemy".

While the nature of power structures will become clear as we go along, imagine them, to begin with, as institutions; or more accurately, as the systems in which we live and work (which we shall here simply call systems).

Notice that systems have an immense power—over us, because we have to adapt to them to be able to live and work; and over our environment, because by organizing us and using us in a specific ways, they decide what the effects of our work will be.

The power structures determine whether the effects of our efforts will be problems, or solutions.

Diagnosis

How suitable are the systems in which we live and work for their all-important role?

Evidence shows that they waste a lion's share of our resources. And that they either cause our problems, or make us incapable of solving them.

The reason is the intrinsic nature of evolution, as Richard Dawkins explained it in "The Selfish Gene".

"Survival of the fittest" favors the systems that are by nature predatory; not the ones that are useful.

This excerpt from Joel Bakan's documentary "The Corporation" (which Bakan as law professor created to federate an insight he considered essential) explains how the corporation, the most powerful institution on the planet, evolved to be a perfect "externalizing machine" ("Externalizing" means maximizing profits by letting someone else bear the costs, such as the people and the environment), just as the shark evolved to be a perfect "killing machine". This scene from Sidney Pollack's 1969 film "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" will illustrate how our systems affect our own condition.

Why do we put up with such systems? Why don't we treat them as we treat other human-made things—by adapting them to the purposes that need to be served?

The reasons are interesting, and in holotopia they'll be a recurring theme.

One of them we have already seen: We do not see things whole. When we look in conventional ways, the systems remain invisible for similar reasons as a mountain on which we might be walking.

A reason why we ignore the possibility of adapting the systems in which we live and work to the functions they have in our society, is that they perform for us a different function—of providing structure to power battles and turf strifes. Within a system, they provide us "objective" and "fair" criteria to compete; and in the world outside, they give us as system system "competitive edge".

Why don't media corporations combine their resources to give us the awareness we need? Because they must compete with one another for our attention—and use only "cost-effective" means.

The most interesting reason, however, is that the power structures have the power to socialize us in ways that suit their interests. Through socialization, they can adapt to their interests both our culture and our "human quality".

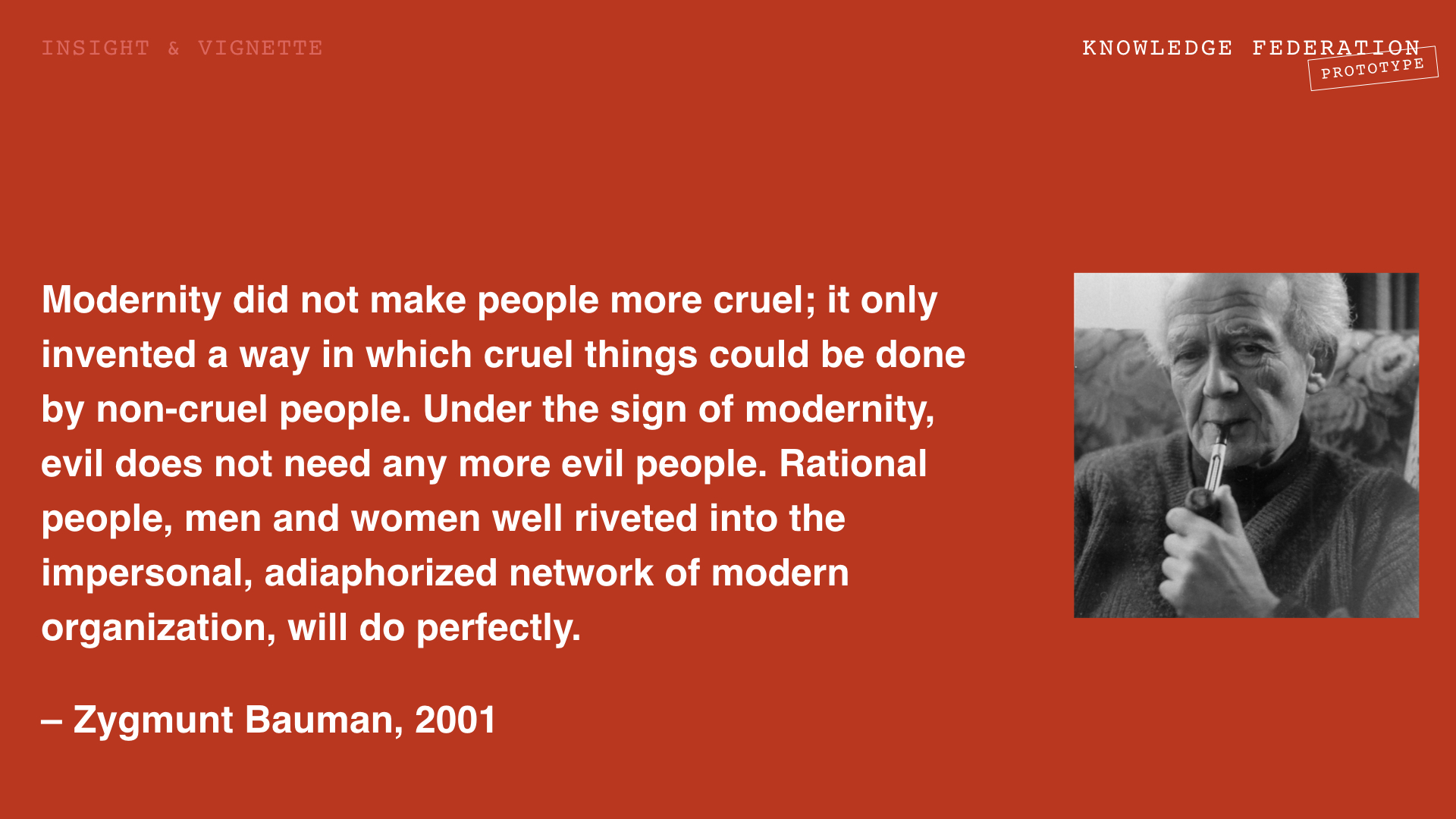

A result is that bad intentions are no longer needed for cruelty and evil to result. The power structures can co-opt our sense of duty and commitment, and even our heroism and honor.

Zygmunt Bauman's key insight, that the concentration camp was only a special case, however extreme, of (what we are calling) the power structure, needs to be carefully digested and internalized: While our ethical sensibilities are focused on the power structures of yesterday, we are committing the greatest massive crime in human history (in all innocence, by only "doing our job" within the systems we belong to).

Our civilization is not "on the collision course with nature" because someone violated the rules—but because we follow them.

Remedy

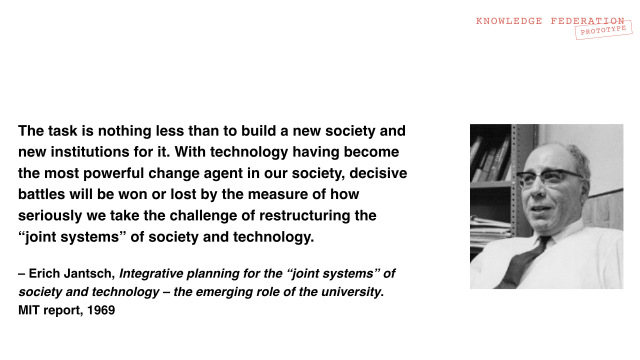

The fact that we will not "solve our problems" unless we learned to collaborate and adapt our systems to their contemporary roles and our contemporary challenges has not remained unnoticed. Alredy in 1948, in his seminal Cybernetics, Norbert Wiener explained why competition cannot replace 'headlights and steering'. Cybernetics was envisioned as a transdisciplinary academic effort to help us understand systems, so that we may adapt their structure to the functions they need to perform.

The very first step the founders of The Club of Rome did after its inception in 1968 was to convene a team of experts, in Bellagio, Italy, to develop a suitable methodology. They gave "making things whole" on the scale of socio-technical systems the name "systemic innovation"—and we adopted that as one of our keywords.

The Knowledge Federation was created as a system to enable federation into systems. To bootstrap systemic innovation. The method is to create a prototype, and a transdiscipline around it to update it continuously. This enables the information created in disciplines to be woven into systems, to have real or systemic impact.

The prototypes are created by weaving together design patterns. Each of them is a issue-solution pair. Hence each roughly corresponds to a discovery (of an issue), and an innovation (a solution). A design pattern can then be adapted to other design challenges and domains. The prototype shows how to weave the relevant design patterns into a coherent whole.

While each of our prototypes is an example, the Collaborology educational prototype is offered as a canonical example. It has about a dozen design patterns, solutions to questions how to make education serve transformation of society—instead of educating people for society as is.

Each prototype is also an experiment, showing what works in practice. Our very first prototype of this kind, the Barcelona Ecosystem for Good Journalism 2011, revealed that the prominent experts in a system (journalism) cannot change the system they are part of. The key is to empower the "young" ones. We created The Game-Changing Game. And The Club of Zagreb.