STORIES

Contents

- 1 Federation through Stories

- 1.1 What the giants have been telling us

- 1.2 These stories are vignettes

- 1.3 Design epistemology

- 1.4 Knowledge federation

- 1.5 Reflection

- 1.6 Systemic innovation

- 1.7 Reflection

- 1.8 Guided evolution of society

- 1.9 Reflection

- 1.10 Our story

- 1.10.1 How Engelbart's dream came true

- 1.10.2 Systemic innovation must grow out of systems science research

- 1.10.3 Jantsch's legacy lives on

- 1.10.4 We came here to build a bridge

- 1.10.5 Knowledge Federation was conceived by an act of bootstrapping

- 1.10.6 Knowledge Federation is a federation

- 1.10.7 The Lighthouse

- 1.10.8 Leadership and Systemic Innovation

Federation through Stories

What the giants have been telling us

The invisible elephant

It has been said that a visionary is a person who can look at what we all are looking at, and see something entirely different. The distinguishing characteristic of the people we are calling giants is that they have an uncommon faculty of vision – which allows them to "see through" the details, see the big picture they compose together, see what wants to or needs to emerge.

The most impactful, powerful and interesting ideas are without doubt those that are challenging or changing our very "order of things" or paradigm. But they also present the largest challenge to communication. A shared paradigm is what enables us to communicate! And the paradigm where new ideas will make sense is still out of reach.

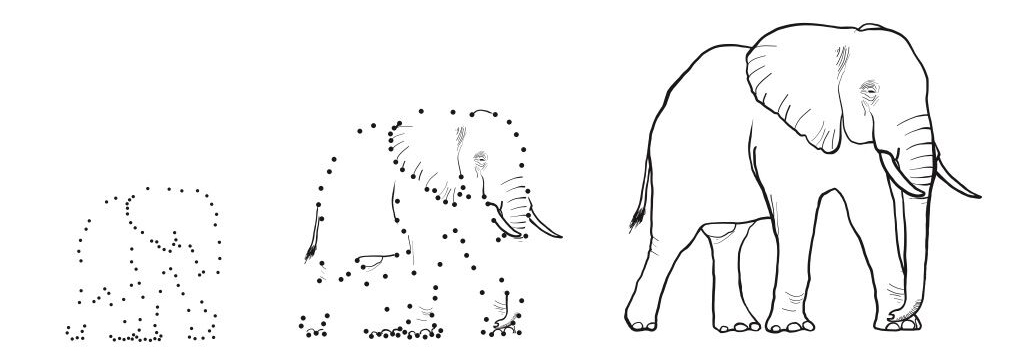

So the giants end up appearing to us like those proverbial blind or blind-folded men touching the elephant. The giants are of course not blind – they are visionaries! But it's the elephant that is invisible, because it's nonexistent. The giants don't have a common language to describe the large animal. So we hear them talk about "the fan" and "the hose" and "the rope" – things that really don't fit together at all; while it's really the ear and the trunk and the tail of that big thing that they are pointing to.

Please be mindful of the subtlety this is pointing to: Our goal will not be to discover what Doug Engelbart or any of the giants "really saw"; even they wouldn't be able to tell us that, if they were still around. What really interests us is to see the elephant – and we'll use freely what the giants said and saw as hints and roadsigns.

Our goal is to materialize the elephant

Our basic strategy, how we want to handle this situation, is to "connect the dots" – to show the whole thing. Initially, of course, all we can hope to show will be just enough for its basic shape for it to become discernible. When that is in place, interest and enthusiasm will do the rest. At that point we've planned to organize the connecting of the dots as a collective activity, a large-scale social game. Just imagine all the fun we'll have discovering or creating all those details together!

And isn't this – augmenting our collective capability to connect the dots, to see collectively where we are going and may need to be going – what our initiative is really all about?

These stories are vignettes

New thinking made easy

Thinking in a new way has always been a challenge. The technique we are using here – the vignettes – is in essence what the journalists use to make relevant or complex ideas accessible. They tell them through an example, a personal story!

If suitably chosen, these stories will allow us to "step into the shoes" of giants, "see through their eyeglasses", be able to see and experience as they did, be moved by the insight that motivated them to make great designs, or theories.

By connecting the vignettes into threads, we compose a whole that is larger (more moving, and effective) than any of them alone. The threads add a dramatic effect, they let the ideas of giants enhance one another. They allow us to see how harmoniously their ideas fit together. We begin to be able to discern the elephant ourselves.

These stories are chosen to show the elephant

The specific stories are chosen here – from a large repertoire of possibilities – because their main protagonists are the giants whom we consider to be the suitable icons for our four main keywords – the ones we've used on the front page to introduce the four main aspects or sides of our initiative. So they'll be suitable to give a down to earth feel to our still abstract animal, by giving the reality touch to our four still unfamiliar concepts we are using to describe it – design epistemology, knowledge federation, systemic innovation and guided evolution of society. So we now introduce them in that order.

We conclude by telling briefly our own story, how we undertook to continue what those giants have begun.

Design epistemology

Modern physics has a gift to the world

(T)he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

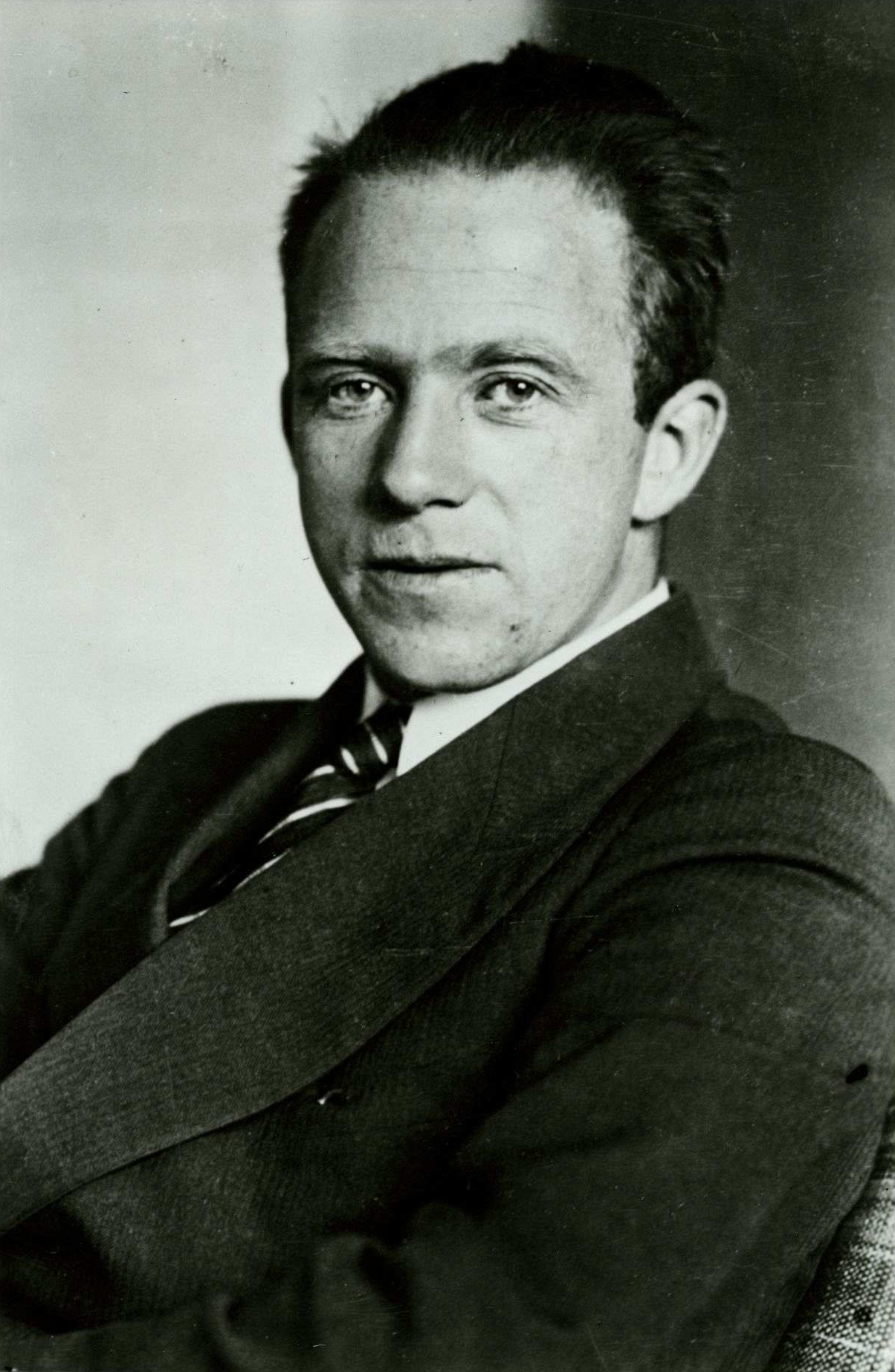

Werner Heisenberg got a Nobel Prize in 1932, "for the creation of quantum mechanics" which he did while he was still in his twenties. He was the man about his work Nils Bohr – his elder colleague – would later say "We are all agreed that your theory is crazy. The question that divides us is whether it is crazy enough to have a chance of being correct."

And so in 1958 this giant of physics looks back at the whole experience of modern physics, and realizes that it has an invaluable gift for humanity that the humanity has not yet received. To remedy that, he writes "Physics and Philosophy" (subtitled "the revolution in modern science"), from which the above excerpt is taken.

In this manuscript Heisenberg explained how science rose to prominence based on its fascinating successes in deciphering the secrets of nature. And how, as a side effect, the specific way of looking at the world and speaking that led to those successes in the specialized domains of science became dominant or also in general culture. And how this frame of concept was so narrow and rigid that

it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our language that had always belonged to its very substance, for instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul or of life.

Since

the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided,

whatever failed to fit this reality picture was considered unreal. This in particular applied to those elements of culture in which our ethical sensibilities were rooted such as religion, which

seemed now more or less only imaginary. (...) The confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind.

Heisenberg then explained how modern physics disproved this "narrow frame"; and concluded that

one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century.

What exactly happened

The key to understanding how exactly this "dissolution of the rigid frame" happened is the so-called double-slit experiment. You'll easily find a more thorough explanation online; so here's a very concise one.

Imagine a source of electrons shooting electrons toward a screen - which, like the old-fashioned TV screen, remains illuminated at the places where an electron landed. Imagine that between the source of electrons and the screen is a plate pierced by two parallel slits, so that the only way an electron can reach the screen is to pass through one of those slits.

It is possible to observe, when an electron is emitted, which slit it has passed through. And when that is done, each electron behaves as conventional particles do – it passes through one of the slits and lands on the corresponding spot on the screen.

When, however, the way the electrons travel is not observed , the electrons behave just as the waves would – they pass through both slits and create an interference pattern on the screen.

The natural question – whether the electrons are waves or particles – thus turns out to have an unexpected answer: They are neither!

And so the scientists have been compelled to conclude that "wave" and "particle" are concepts and corresponding behavioral patterns that we have acquired through experience with common objects, such as the surface of water and the pebbles. That the electrons are simply something different – and that they behave unlike anything we have in experience.

In his book Heisenberg talks about the physicists unable to describe the behavior of small particles of matter in conventional language. The language of mathematics still works – but the common language and common logic doesn't!

And then came Wittgenstein

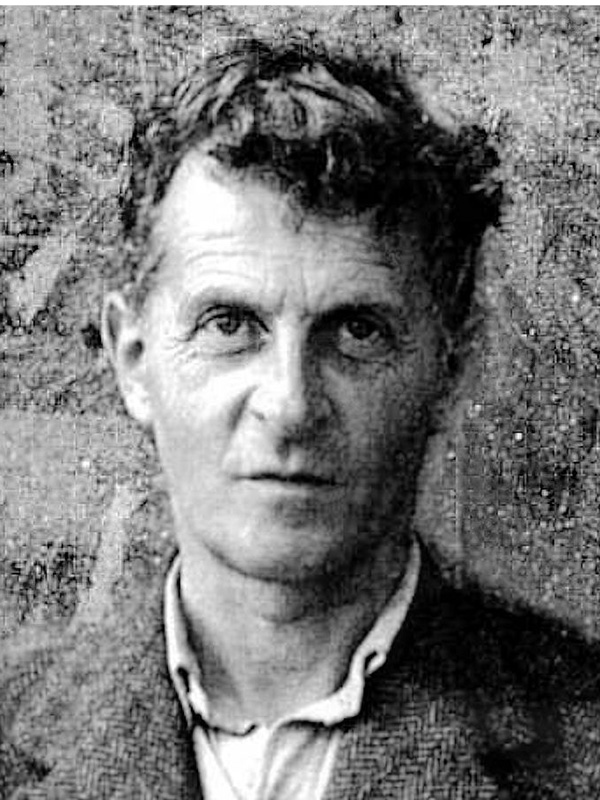

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

We should not leave this all-important theme without at least mentioning the philosophy of language, and Wittgenstein – and his closely confluent insights.

We've overheard it said that all of philosophy had been footnotes to Plato; and then came Wittgenstein. We let the above epigram from the ending of Tractacus represent Wittgenstein's message to us.

When at the beginning of Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein lets us listen to a mason issue commands to his assistant in a highly reduced language ("block", "pillar", "slab" and "beam"), what the mason, and Wittgenstein, are really telling us is that the words find their meaning in a specific practical activity or "language game". And that when we take them out of that context and stretch their meanings in (for example) a speculation about the nature of reality, then their meanings tends to be lost, and with them also the meaning of our discourse.

It might seem that we are forever stuck in a paradigm; but there's a way out – by stepping "through the mirror (see Federation through Images).

Wittgenstein's ideas can still be considered controversial, and rightly so – they challenge the very roots of our paradigm, of our academic "language game". A lively illustration is in a little book titled "Wittgenstein's Poker". The book zooms in on specific "ten minutes in the history of philosophy", where Karl Popper (who visited Cambridge and gave a talk) and Wittgenstein are in a heated discussion – at the end of which Wittgenstein demonstratively throws down the (fire) poker he was holding in his hand while gesticulating, and storms out of the room.

What Heisenberg didn't tell us

In "Uncommon Sense" Robert Oppenheimer – Heisenberg's famous colleague and the leader of the WW2 Manhattan project – observed that even our common sense, however solidly objective it might appear to us, is really derived from our experience with common objects. And that it turns out to no longer work when we meet some of the things that we don't have in experience, such as small particles of matter.

In "Metaphors We Live By" George Lakoff – a leading researcher in cognitive linguistics – showed by studying language how our abstract reasoning is shaped through experience with simple physical objects and their relationships. Jean Piaget – a leading researcher in cognitive psychology – showed that in another way, by studying how the children develop their conception of reality. In the sociology classics "Social Construction of Reality" Berger and Luckmann explained how reality pictures are socially constructed. And how they have a tendency to acquire independence and become "universal theories" – and then be used to legitimize the existing social order (recall Galilei in house arrest).

We turn the above and numerous other similar insights into a big picture with the help of this brief excerpt from Benjamin Lee Whorf's essay – which was (remarkably!) written already in the 1940s, and published as part of the book "Language, Thought and Reality" a decade later.

It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier. Either it must bury its dead, close its ranks, and go forward into a landscape of increasing strangeness, replete with things shocking to a culture-trammelled understanding, or it must become, in Claude Houghton’s expressive phrase, the plagiarist of its own past."

What Heisenberg did tell us

In his book Heisenberg does not give us this transdisciplinary view of his theme, because just the experience of modern physics, when carefully reviewed, turns out to be sufficient to make his point.

Which is that science gave us a certain set of concepts, and a way of looking at the world, which quite naturally appeared to us to be the solution to the age-old challenge – of seeing the reality as it truly is. And hence to create real knowledge!

But the experience of science, it turned out, led us to an entirely different conclusion – that not only the conceptual machinery of the 19th century science will give us that, but that we have no solid reason to believe that any set of concepts and any way of looking at the world will show us "the reality as it truly is"!

Heisenberg describes how a certain (rational-mechanistics) way of thinking and looking at the world and speaking enabled the scientists to construct experimental machinery and look at small fragments of matter. And how when they did that, they found patterns of behavior that contradicted that very way of looking at the world. Hence the whole affaire ended up having the structure of a proof by contradiction – which, according to that same way of looking at the world, is a rigorous way to prove things wrong.

We are at a turning point

The Enlightenment empowered the human reason to rebel against the tradition and freely explore the world. As we have seen, several centuries of exploration brought us to another turning point in this process – where our reason has become capable of self-reflecting; of seeing its own limitations, and blind spots.

What we are still lacking – and which should logically follow as the next step in this age-old evolutionary process – is the capability to correct those blind spots; by creating new ways to look at the world, freely yet responsibly. And to develop that, the creation of good ways to see the world as a praxis.

But isn't that what we've been talking about all along?

Knowledge federation

To be useful, information technology requires new thinking

These two sentences were intended to frame Douglas Engelbart's message to the world – which was to be delivered at a panel organized and filmed at Google in 2007.Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking.

An epiphany

In December of 1950 Engelbart was a young engineer just out of college, engaged to be married, and freshly employed. His life appeared to him as a straight path to retirement. And he did not like what he saw.

So there and then he made a decision – to direct his life's work in a way that will maximize its benefits to the mankind.

Facing now an interesting optimization problem, this young engineer spent three months thinking intensely how exactly to go about solving it. Then he had an epiphany: The computer had just been invented. And the humanity had all those problems that it didn't know how to solve. What if...

To be able to pursue his vision, Engelbart quit his job and enrolled in the doctoral program in computer science at U.C. Berkeley.

Silicon Valley failed to hear its giant in residence

It took awhile for the people in Silicon Valley to realize that the core technologies that led to "the revolution in the Valley" were neither developed by Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, nor at the XEROX research center where they took them from – but by Douglas Engelbart and his SRI-based research team. On December 9, 1998 a large conference was organized at Stanford University to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Engelbart's Demo, where the networked interactive digital media technology – which is today common – was first shown to the public. Engelbart received the highest honors an inventor could have, including the Presidental award and the Turing prize (a computer science equivalent to Nobel Prize). Allen Kay (a Silicon Valley personal computing pioneer, and a member of the original XEROX team) remarked "What will the Silicon Valley do when they run out of Doug's ideas?".

And yet it was clear to Doug – and he also made it clear to others – that the core of his vision was neither implemented nor understood. Doug felt celebrated for wrong reasons. He was notorious for telling people "You just don't get it!" The slogan "Douglas Engelbart's Unfinished Revolution" was coined as the title of the 1998 Stanford University event, and it stuck.

On July 2, 2013 Doug passed away, celebrated and honored – yet feeling he had failed.

The elephant was in the room

What is it that Engelbart saw, but was unable to communicate to all those famously smart people?

If we now tell you that the solution to this riddle is precisely the elephant we've been talking about, that whenever Doug was speaking or being celebrated, this elephant was present in the room but remained ignored – you probably won't believe us. A huge, spectacular animal in the midst of a university lecture hall – should that not be a front-page sensation and the talk of the town? (It may be better to imagine an elephant in a room at the inception of the last Enlightenment, when some people may have heard that such a huge animal existed, but nobody had yet seen one.)

So it might be helpful to consider the following excerpt (from an interview that Doug gave as a part of a Stanford University research project), where Doug is recalling the very inception of his insight, the thought process that later led to his project:

I remember reading about the people that would go in and lick malaria in an area, and then the population would grow so fast and the people didn't take care of the ecology, and so pretty soon they were starving again, because they not only couldn't feed themselves, but the soil was eroding so fast that the productivity of the land was going to go down. Sol it's a case that the side effects didn't produce what you thought the direct benefits would. I began to realize it's a very complex world. I began to realize it's a very complex world. (...) Someplace along there, I just had this flash that, hey, what that really says is that the complexity of a lot of the problems and the means for solving thyem are just getting to be too much. So the urgency goes up. So then I put it together that the product of these two factors, complexity and urgency, are the measure for human organizations or institutions. The complexity/urgency factor had transcended what humans can cope with. It suddenly flashed tthat if you could do something to improve human capability to deal with that, then you'd realy contribute something basic. That just resonated. Then it unfolded rapidly. I think it was just within an hour that I had the image of sitting at a big CRT screen with all kinds of symbols, new and different symbols, not restricted to our old ones. The computer could be manipulating, and you could be operating all kinds of things to drive the computer. The engineering was easy to do; you could harness any kind of a lever or knob, or buttons, or switches, you wanted to, and the computer could sense them, and do something with it.

Isn't this a quite wonderful example of systemic thinking?

And if you are still in doubt – consider these first four slides from the end of Doug's career, which were intended to be part of his "A Call to Action" presentation at Google in 2007.

You will notice that Doug's call to action had to do with changing our way of thinking. And that Doug introduced the new thinking with a variant of the bus with candle headlights metaphor we used to introduce our four main keywords.

And then there's the third slide, which introduces a whole new metaphor – a "nervous system". This was meant to explain Doug's specific intended gift to the emerging new paradigm in knowledge work – to which we'll turn next.

You might be wondering what happened with Engelbart's call to action? How did it fare? If you now google Engelbart's 2007 presentation at Google, you'll find a Youtube recording which will show that these four slides were not even shown at the event (the slides were shown beginning with slide four); that no call to action was mentioned; and that Engelbart is introduced in the subtitle to the video as "the inventor of the computer mouse".

The 21st century enlightenment's printing press

What was really Engelbart's intended gift to humanity? What was it that he saw, which the Silicon Valley "just didn't get"?

The printing press is a fitting metaphor in the context of our larger vision, because the printing press was the key technical invention that led to the Enlightenment, by making knowledge accessible.

If we now ask what technology might play a similar role in the next enlightenment, you will probably answer "the Web" or "the network-interconnected interactive digital media" if you are technical. And your answer will of course be correct.

But there's a catch!

While there can be no doubt that the printing press led to a revolution in knowledge work, this revolution was only a revolution in quantity. The printing press could only do what the scribes were doing – albeit incomparably faster! To communicate, people still needed to write and publish printed pages, and hope that the people who needed what they wrote would find them on a shelf.

The network-interconnected interactive digital media, however, is a disruptive technology of a completely new kind. It is not a broadcasting device, but in a truest sense a nervous system connecting people together!

There are two very different ways in which this sort of nervous system be put to use.

One of them is to use it as the printing press has been used – to increase the efficiency of what the people are already doing. To help them write and publish faster, and more. In the language of our metaphor, we characterize this way as using the new technology to re-implement the candle.

The other way is to reconfigure the document types, and the institutionalized patterns of knowledge development, integration and application, interaction and even the institutions to suit our society's needs, or in other words the function they need to fulfill in this larger whole – by taking advantage of the capabilities and of the very new nature of the new technology. The other way is to develop a new division, specialization and coordination of knowledge work – just as the cells in the human body body have developed through evolution, to take advantage of the nervous system that connects them together.

To see the difference between those two ways of using the technology, to see their practical consequences, imagine if your cells used your nervous system to merely broadcast data to your brain. Think about how this would impact your sanity!

You'll now have no difficulty seeing how our present way of using the technology has affected our collective intelligence!

In 1990 – just before the Web, and well before the mobile phone – Neil Postman would observe:

The tie between information and action has been severed. ...It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it.

Engelbart's legacy

Engelbart wanted to show us, and to help materialize, the elephant; but since we couldn't see it – he ended up with only a little mouse in his hand (to his credit)!

So if we would now undertake to give him proper credit – what is it that Engelbart must be credited for?

As we speak, please notice how systematically this unusual mind was putting together all the necessary vital pieces or building blocks – so that the elephant may come into being.

One of them we've already mentioned – the "nervous system", for which Doug's technical keyword was CoDIAK (for Concurrent Development, Integration and Application of Knowledge). It's the 'nervous system'. That – and not "the technology" – is what Engelbart and his team showed on their 1968 famous demo. The demo showed people interacting directly with computers, and through computers – via a network by which the computers were connected – with each other. Doug and his team experimented to make this interaction as direct as possible; with a "chorded keyset" under his left hand, a mouse with three buttons under his right hand, and a computer screen before his eyes, a knowledge worker became able to "develop. integrate and apply knowledge" in collaboration, and concurrently with others – without ever even moving his body!

To get an idea of the importance of this contribution, think about what a functioning "collective nervous system" could do to our collective capability to deal with complexity and urgency. Imagine yourself walking toward a wall, and that your eyes see that – but they are trying to communicate it to your brain by writing academic articles in some specialized field of knowledge.

The second key Engelbart's contribution – which is, as we have just seen, necessary if we should take advantage of the first one – was what we've been calling systemic innovation. Engelbart created (to our knowledge) the very first methodology for systemic innovation – already in 1962, six years before the systems scientists met in Bellagio to develop their own approach to it (which will be part of our next story). Engelbart called his method "augmentation", and conceived as a way to "augment human capabilities", individual and collective, by combining elements of the "human system" and the "tool system". Systemic innovation he called "human system – tool system co-evolution", or more simply "bootstrapping".

We leave the rest – to see how the "open hyperdocument system", the "networked improvement community", the "dynamic knowledge repository" and numerous other Engelbart's inventions were essential building blocks in a new order of things, or knowledge work paradigm, or vital organs of our metaphorical elephant. You'll find them explained in the mentioned videotaped 2007 presentation at Google. You may then also notice that they don't really make the kind of sense they're supposed to make – when presented outside of the context that the first three slides were supposed to provide (the elephant).

We conclude that while Engelbart was recognized, and celebrated, as a technology developer – his contribution was to human knowledge – and hence in the proper sense academic.

Bootstrapping – the unfinished part

In a similar vein, there can hardly be any doubt about what exactly it was that, Doug felt, he was leaving unfinished. It's what he called "bootstrapping" – which we've adopted as one of our keyword.

Bootstrapping was so central to Doug's thinking, that when he and his daughter Christina created an institute to realize his vision, they called it "Bootstrap Institute" – and later changed the name to "Bootstrap Alliance" because, as we shall see in a moment, an alliance rather than an institute is what's needed to bring bootstrapping to fruition. Engelbart would begin the "Bootstrap Seminar" (which he taught through he Stanford University to explain his vision and create an alliance around it) by sharing his portfolio of vignettes – which were illustrating the wonderful and paradoxical challenge of people to see an emerging paradigm. Then he would have the participants discuss their own experiences with paradigm shifts in pairs. Then he would talk more about the paradigms.

When it became clear that Engelbart's long career was coming to an end, "Bootstrap Dialogs" were recorded in the Stanford University's film studio as a last record of his message to the world. Jeff Rulifson and Christina Engelbart – his two closest collaborators in the later part of his career – were conversing with Doug, or indeed mostly explaining his vision in his presence, with Doug nodding his head. And when they would turn to him and ask "So what do you say about this, Doug?" he would invariably say something like "Oh boy, I think somebody should really make this happen. I wonder who that might be?" We made an examle, {https://youtu.be/cRdRSWDefgw this three-minute excerpt], available on Youtube – where Doug also talks about the meaning of "bootstrapping".

The word itself should remind you of "lifting yourself up by pulling your bootstraps" – which is of course in physical sense impossible, yet the magic works as a metaphor. The idea is to use your intelligence to boost your intelligence. Or applied to systemic innovation – to recreate one's own system, and thus become able to recreate other systems.

To Engelbart "bootstrapping" meant several related things.

First of all – and this is the succinct way to understand the core of his vision – Engelbart, as a systemic thinker, clearly saw that the most effective way one can invest his creative capabilities (and make "the largest contribution to humanity") is by applying them to creativity itself – and improving everyone's creative capabilities, and our ability to make good use of the results thereof.

Furthermore, Doug the systemic thinker knew that positive feedback leads to exponential growth. And so he saw bootstrapping as the only way our capabilities to cope with the accelerated growth of the "complexity times urgency" of our problems.

And finally – Doug saw that talking about how to "solve our problems" or "improve our systems", or writing academic articles about that, is just not good enough. (He saw, in other words, what we've been calling the Wiener's paradox.) So bootstrapping then emerges as what we must do if we really want to make a difference.

Reflection

Our opportunity and challenge

Our vision statement offers a succinct rendition of Engelbart's core vision – and points to the nature of the situation the new information technology has put us in. We offer it to you for reflection, before you continue to process our next story.

Systemic innovation

Democracy for the third millennium

Erich Jantsch reached and reported the above conclusion quite exactly a half-century ago – right around the time when Doug Engelbart and his team were showing their demo.The task is nothing less than to build a new society and new institutions for it. With technology having become the most powerful change agent in our society, decisive battles will be won or lost by the measure of how seriously we take the challenge of restructuring the “joint systems” of society and technology.

We weave these two histories together – the story of Engelbart and the story of Jantsch – in the second book of Knowledge Federation trilogy. So far we've seen that we need the capability to rebuild institutions and institutionalized patterns of work and interaction to be able to take advantage of fundamental insights and of new information technology. (Or in the language of Thomas Kuhn, we have seen that this is necessary to resolve the reported anomalies in those two key domains of knowledge work). By telling about Erich Jantsch we'll be able to bring in the third. How shall we call it? Our choice is in the title of this section – which is also the subtitle of the book we've just mentioned. We could have just as well talked about "sustainability" or "thrivability" or "creative action". Why we chose "democracy" will hopefully become transparent after you've read a bit further.

First things first

Jantsch got his doctorate in astrophysics in 1951, when he was only 22. But having recognized that more physics is not what our society most urgently needs, he soon got engaged in a study (for the OECD in Paris) of what was then called "technological planning" – i.e. of the strategies that different countries (the OECD members) used to orient the development and deployment of technology. (Are there such strategies? – you might rightly ask. Isn't it "the market and only the market" the answers to such questions? You'll have no difficulty noticing the underlying big question – What is guiding us toward our future? And that how we answer this question splits us into into two (subcultures, or paradigms): Those of us who believe in "the invisible hand" – and those who don't. Recall Galilei...)

And so when The Club of Rome was to be initiated (fifty years ago at the time of this writing) as an international think tank whose mission was to evolve and to be the evolutionary guidance or the 'headlights' to our global society (as we shall see in our next story), it was natural that Jantsch would be chosen to put the ball in play, by giving a keynote talk.

How systemic innovation got conceived

With a doctorate in physics, it was not difficult to Jantsch to put two and two together and see what needed to be done. If our civilization is on a disastrous course, if it lacks (as Engelbart put it) suitable headlights and braking and steering controls, or (to use a cybernetician's more scientific tone) suitable "information and control", then there's a single capability that we as society need to be able to correct this problem – the capability to rebuild our systems. So that we may become capable of seeing where we are going, and steering.

So right after The Club of Rome's first meeting, Jantsch gathered a group of creative leaders and researchers, mostly from the systems community, in Bellagio, Italy, to put together the necessary insights and methods. The result was a systemic innovation methodology. By calling it "rational creative action", Jantsch suggested a message that is of our central interest: Certainly there are many ways in which we can be creative. But if our creative action is to be rational – then here is what we need to do.

Rational creative action begins with forecasting, which explores different future scenario, and ends with an action selected to enhance the likelihood of the desired scenario or scenarios. What they called "planning" had nothing to do with the kind of planning that was at the time used in the Soviet Union:

[T]he pursuance of orthodox planning is quite insufficient, in that it seldom does more than touch a system through changes of the variables. Planning must be concerned with the structural design of the system itself and involved in the formation of policy.”

Do we really need systemic innovation? Can't we just rely on "the survival of the fittest" and "the invisible hand"? Jantsch observes that the nature of the problems we create when relying on the "invisible hand" is compelling us to develop systemic innovation as our next evolutionary step.

We are living in a world of change, voluntary change as well as the change brought about by mounting pressures outside our control. Gradually, we are learning to distinguish between them. We engineer change voluntarily by pursuing growth targets along lines of policy and action which tend to ridgidify and thereby preserve the structures inherent in our social systems and their institutions. We do not, in general, really try to change the systems themselves. However, the very nature of our conservative, linear action for change puts increasing pressure for structural change on the systems, and in particular, on institutional patterns.

Back to democracy

You might now already be having an inkling of the contours of the elephant; how all these seemingly disparate pieces – the way we use the language, the way we use information technology, and the way we go about resolving the large contemporary issues – can snuggly fit together in two entirely different ways!

Take, for example, the word "democracy". In the old paradigm, democracy is what it is – the "free press", "free elections", the representative bodies. As long as they are all there, by definition – we live in a democracy. The nightmare scenario in this order of things is a dictatorship, where the dictator has taken away from the people all those conventional instruments of democracy, and he's ruling all by himself.

But there is another, emerging way to look at the world, and at democracy in particular – to consider it as a social order where the people are in control; where they can control their society, and steer it and choose their future. The nightmare scenario in this order of things is what Engelbart showed on his second slide mentioned above – it's an order of things where nobody has control! Simply because the whole thing is structured so that nobody can see where the whole thing is headed, or change its course.

Back to bootstrapping

In this second order of things (where we don't rely our civilization's and our children's future on "the invisible hand" but use the best available knowledge to see where we are headed and steer

– bootstrapping is readily seen as the very next and vitally important step. We must adapt our institutions to give us the capabilities we lack. But those institutions – that's us, isn't it? Nobody has the power, or the knowledge, to order for example the university to recreate itself in a certain way. The university itself will need to do that!</p>The emerging role of the university

If systemic innovation is the necessary new capability that our systems and our civilization at large now require, to be able to steer a viable course into the future – then who (that is, what institution) may be the most natural and best qualified to foster this capability? Jantsch concluded that the university (institution) will have to be the answer. And that to be able to fulfill this role, the university itself will need to update its own system.

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal. It may have to become a political institution, interacting with government and industry in the planning and designing of society’s systems, and controlling the outcomes of the introduction of technology into those systems. This new leadership role of the university should provide an integrated approach to world systems, particularly the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.”In 1969 Jantsch spent a semester at the MIT, writing a 150-page report about the future of the university, from which the above excerpt was taken, and lobbying with the faculty and the administration to begin to develop this new way of thinking and working in academic practice.

Evolution is the key

Jantsch spent the last decade of his life living in Berkeley, teaching sporadic seminars at U.C. Berkeley and writing prolifically. Ironically, the man who with such passion and insight wrote about how the university would need to change to help us master our future, and lobbied for such change – never found a home and sustenance for his work at the university.

In 1980 Jantsch published two books about "the evolutionary paradigm" – whose purpose was to inform us how to understand, and steer, our societal evolution. He passed away after a short illness, only 51 years old. An obituarist commented that his unstable income and inadequate nutrition might have contributed to his fate. In his will Jantsch asked that his ashes be tossed into the ocean, "the cradle of evolution".

In that same year Ronald Reagan became the 40th U.S. president on the agenda that the market, or the free competition, is the only thing we can rely on. That "simple-minded theory", as Norbert Wiener called it, marks both our political life and our technological innovation still today. "The invisible hand" – whether it exists or not – is what now determines what our future will be.

Reflection

The future of innovation

It has been observed that the future is no longer what it used to be. But what is it then, really? In what way will it be different?

We've already answered this question, by talking about the guided evolution of society. The steering, however, the key new capability we need to be able to do that – is the capability at which Engelbart also stopped, which constitutes the essence of his "unfinished revolution". What we are talking about is our ability to change the actual real-life institutionalized patterns or thought and action, or in a word – systems.

If you allow yourself to spend a few moments with this reflection about the future of innovation, we expect that the result will be amazement: How can it be possible that a creative frontier of such a paramount importance has been ignored for so long – at this advanced stage of our civilization; and in spite of what the giants have been telling us (see Federation through Stories).

A partial explanation can be found on our front page, by which we introduced our initiative: Owing to the kind of knowledge we've created and prioritized, we ended up being a people lost among the trees and not seeing the forest. You may now imagine that the forest is on a mountain, and that this mountain – however paramount its size and importance may be – has of course remained ignored.

To show this mountain will be our purpose in Federation through Applications. By showing a collage of prototypes, which have been designed strategically to cover the space of the 'mountain', we undertake to make what's been ignored visible and open to co-creative engagements.

But this explanation is still insufficient to do justice to a paradox of this magnitude. And indeed – it will turn out – it is really just half the story. The other half will be the theme of Federation through Conversations, where we will see that our ignorance of systems has really been the consequence of the nature of our socialization – and on a deeper level of the way in which we have been evolving as culture, and as society. We shall see that to be able to intervene in this evolution is the core of our present historical task – and the true departure point of our next paradigm.

The question we turn to now is who – that is, what institution, and in what way, will enable us to develop this most central capability, of steering, of changing course, of guiding our future – by correcting our systems.

Guided evolution of society

Just another hero

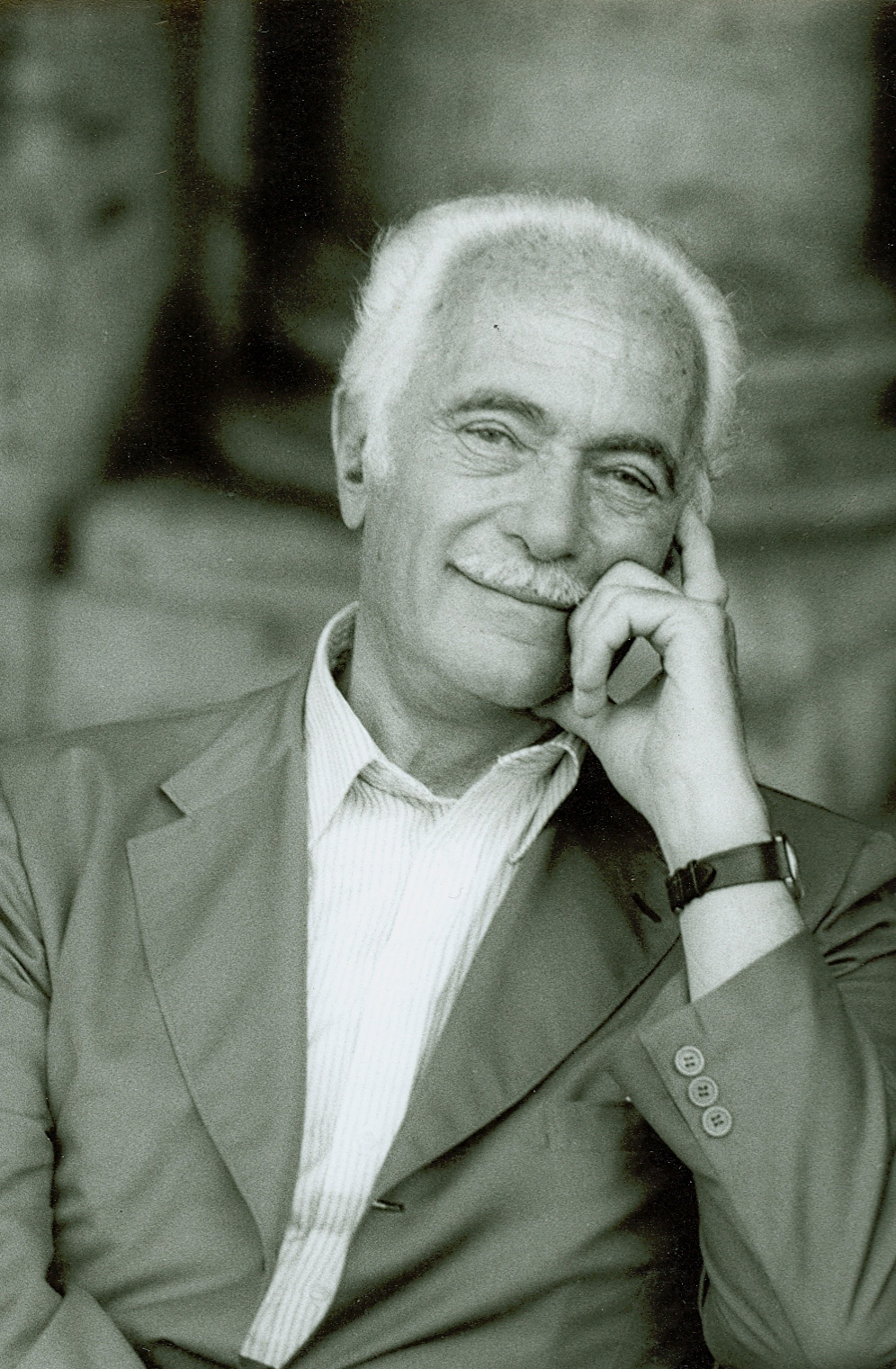

The human race is hurtling toward a disaster. It is absolutely necessary to find a way to change course.Aurelio Peccei – the co-founder, firs president and the motor power behind The Club of Rome – wrote this in 1980, in One Hundred Pages for the Future, based on this global think tank's first decade of research.

Peccei was an unordinary man. In 1944, as a member of Italian Resistance, he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured for six months without revealing his contacts. Here is how he commented his imprisonment only 30 days upon being released:

My 11 months of captivity were one of the most enriching periods of my life, and I regard myself truly fortunate that it all happened. Being strong as a bull, I resisted very rough treatment for many days. The most vivid lesson in dignity I ever learned was that given in such extreme strains by the humblest and simplest among us who had no friends outside the prison gates to help them, nothing to rely on but their own convictions and humanity. I began to be convinced that lying latent in man is a great force for good, which awaits liberation. I had a confirmation that one can remain a free man in jail; that people can be chained but that ideas cannot.

Peccei was also an unordinarily able business leader. While serving as the director of Fiat's operations in Latin America (and securing that the cars were there not only sold but also produced) Peccei established Italconsult, a consulting and financing agency to help the developing countries catch up with the rest. When the Italian technology giant Olivetti was in trouble, Peccei was brought in as the president, and he managed to turn its fortunes around. And yet the question that most occupied Peccei was a much larger one – the condition of our civilization as a whole; and what we may need to do to take charge of this condition.

How to change course

In 1977, in "The Human Quality", Peccei formulated his answer as follows:

Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world.

And to leave no doubt about this point, he framed it even more succinctly:

The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future.

On the morning of the last day of his life (March 14, 1984), while working on "The Club of Rome: Agenda for the End of the Century", Peccei dictated to his secretary from a hospital bed that

human development is the most important goal.

Peccei's and Club of Rome's insights and proposals (to focus not on problems but on the condition or the "problematique" as a whole, and to handle it through systemic and evolutionary strategies and agendas) have not been ignored only by "climate deniers", but also by activists and believers.

Reflection

Connecting the dots

In what way can "a great cultural revival" realistically happen?

The key strategic insight here is to see why a very large change can be easy, even when smaller and obviously necessary changes might seem impossible: You cannot put an elephant's ear on a mouse – even if this might vastly improve his hearing.

On the other hand, large, sweeping changes can happen by a landslide, as each change, like a falling domino, naturally leads to another.

So the key question is – How to begin such a change?

The natural first step, we propose, is to connect the dots – and see where we are going or out to be going, see how all the pieces snuggly fit together.

Already combining Peccei's core insight with the one of Heisenberg will bring us a large step forward

Peccei observed that our future depends on our ability to revive culture, and identified improving the human quality is the key strategic goal. Heisenberg explained how the "narrow and rigid" way of looking at the world that the 19th century science left us with was damaging to culture – and in particular to its parts which traditionally governed human ethical development, notably the religion.

Can we build on what Heisenberg wrote, and recreate religion in an entirely new way – which would support us in "great cultural revival"?

The Garden of Liberation prototype (see Federation through Applications) and the Liberation book (the first in Knowledge Federation Trilogy, see Federation through Conversations) will show that indeed we can! Religion is now often assumed to be no more than a rigid and irrational adherence to a belief system. A salient characteristic of the described religion-reconstruction prototype is to liberate us (that is, both religion and science) from holding on to any dogmatically held beliefs!

Combining the core insights of Jantsch and Engelbart is even easier, as they are really just two sides of a single coin.

Jantsch identified systemic innovation as that key lacking capability in our capability toolkit, which we must have to be able to steer our ride into the future. Engelbart identified it as the capability which we need to be able to use the new technology to our advantage. We now have the technology that not only enables, but indeed demands systemic innovation. What are we waiting for?

When you browse through our collection of prototypes that are provided in Federation through Applications, and see concretely and in detail the larger-than-life improvements of our condition that can be achieved by improving or reconstructing our core institutions or systems, when you see that an avalanche-like or Industrial Revolution-like wave of change that is ready to occur – then you'll have but one question in mind: "Why aren't we doing this?!"

A prototype answer to this most interesting question is given in Federation through Conversations – by weaving together insights of giants in the humanities. We shall see how what we've been calling "our reality picture" is likely to be seen as our doxa – a power-related instrument of socialization that keeps us in a certain systemic status quo (recall Galilei).

We are especially enthusiastic about the prospects of combining together the fundamental, the humanistic and the innovation-and-technology related insights.

Notice how our reifications – identifying public informing with what the journalists are doing, and also science, and education, and democracy and... – with their present systemic implementations – is preventing us from seeing them as systems within the larger system of society, and adapting them to the roles they need to perform, and the qualities they need to have – with the help of the new technology. It is not an accident that Benjamin Lee Whorf was one of Doug Engelbart's personal heroes (Doug considered himself "a Whorfian")! There's never an end to discovering beautiful, and subtle, connections. In our prototype portfolio you'll find numerous examples; but let's here zoom in on just a couple of them.

The Club of Zagreb prototype is our redesign of The Club of Rome, based on The Game-Changing Game prototype. The key point here is to use the insights and the power of the seniors (they are called Z-players) – to empower the young people (the A-players) – to change the systems in which they live and work.

All our answer are, once again, given as prototypes accompanied by an invitation to a conversation through which they will evolve further. By developing those conversations, we'll be seeing and materializing the elephant!

Occupy your university

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewalwrote Erich Jantsch. In this way he provided an answer to the key question this conversation is leading us to – Where might this sort of change naturally begin?

Why blame the Wall Street bankers for our condition? Or Donald Trump? Shouldn't we rather see them as symptoms of a social-systemic condition, in which the flow of knowledge is what may bring healing, and solutions. And this flow of knowledge – isn't that really our job?

Our story

How Engelbart's dream came true

Doug Engelbart passed away on July 2nd, 2013. Less than two weeks later, his desire to see his ideas taken up by an academic community came true! And that community – the International Society for the Systems Sciences – just couldn't have be better chosen.

At this society's 57th yearly conference, in Haiphong Vietnam, this research community began to self-organize according to Engelbart's principles – by taking advantage of new media technology to become "collectively intelligent". And to extend its outreach further into a knowledge-work system, which will connect systemic change initiatives around the world, and help them learn from one another, and from the systems science research. At the conference Engelbart's name was often heard.

Systemic innovation must grow out of systems science research

There is a reason why Knowledge Federation remained the transdiscipline for knowledge federation, why we have not taken up the so closely related and larger goal, of bootstrapping the systemic innovation. If it is to be done properly – and especially if we interpret "properly" in an academic sense – then systemic innovation must grow out of systems science research – which alone can tell us how to understand systems, how to improve them and intervene in them. If we, the knowledge federators, should do our job right, then we must federate this body of knowledge, we must not try to reinvent it!

Jantsch's legacy lives on

Alexander Laszlo was the ISSS President who initiated the mentioned development.

Alexander was practically born into systemic innovation. Didn’t his father Ervin, himself a creative leader in the systems community, point out that our choice was “evolution or extinction” in the very title of one of his books? So the choice left to Alexander was obvious – and he became the leader of conscious or systemic evolution.

Alexander’s PhD advisor was Hasan Özbekhan, who wrote the first 150-page systemic innovation theory, as part of the Bellagio team initiated by Jantsch. He later worked closely in the circle of Bela H. Banathy, who for a period of a couple of decades held the torch of systemic innovation–related developments in the systems community.

We came here to build a bridge

As serendipity would have it, at the point where the International Society for the Systems Sciences was having its 2012 meeting in San Jose, at the end of which Alexander was appointed as the society's president, Knowledge Federation was having its presentation of The Game-Changing Game (a generic, practical way to change institutions and other large systems) practically next door, at the Bay Area Future Salon in Palo Alto. The Game-Changing Game was made in close collaboration with Program for the Future – the Silicon Valley-based initiative to complete Engelbart's unfinished revolution. Doug and Karin Engelbart joined us to hear a draft of our presentation in Mei Lin Fung's house, and for social events. Bill and Roberta English – Doug's right and left hand during the Demo days – were with us all the time.

Louis Klein – a senior member of the systems community – attended our presentation, and approached us saying "I am going to introduce you to some people". He introduced us to Alexander Laszlo and his team.

"Systemic thinking is fine", we wrote in an email, "but what about systemic doing?" "Systemic doing is exactly what we are about", they reassured us. So we joined them in Haiphong.

"We are here to build a bridge", was the opening line of our presentation at the Haiphong ISSS conference, " between two communities of interest, and two domains – systems science, and knowledge media research." The title of the article we brought to the conference was "Bootstrapping Social-Systemic Evolution". We talked about Jantsch and Engelbart who needed each other to fulfill their missions – and never met, in spite of living just across the Golden Gate Bridge from each other. We also shared our views on epistemology and the larger emerging paradigm – and proposed that if the systems research or movement should fulfill its vitally important societal purpose, then it needs to embrace bootstrapping or self-organization as (part of) its mode of operation.

If you've seen the short video we shared on Youtube as "Engelbart's last wish", then you'll see how what we did answers to it quite precisely: We realized that systemic self-organization was beginning at a spot in the global knowledge-work system from which it could most naturally scale further; and we joined it, to help it develop further.

Knowledge Federation was conceived by an act of bootstrapping

Knowledge Federation was initiated in 2008 by a group of academic knowledge media researchers and developers. At our first meeting, in the Inter University Center Dubrovnik (which as an international federation of universities perfectly fitted our later development), we realized that the technology that our colleagues were developing could "make this a better world". But that to help realize that potential, we would need to organize ourselves differently. Our second meeting in 2010, whose title was "Self-Organizing Collective Mind", brought together a multidisciplinary community of researchers and professionals. The participants were invited to see themselves not as professionals pursuing a career in a certain field, but as cells in a collective mind – and to begin to self-organize accordingly.

What resulted was Knowledge Federation as a prototype of a transdiscipline ;and the corresponding way of working. The main idea is natural and simple: a trandsdisciplinary community of researchers and other professionals and stakeholders gather to create a systemic prototype – which can be an insight or a systemic solution for knowledge work or in any domain of interest. In this latter case, this community will usually practice bootstrapping, by (to use Alexander's personal motto) "being the systems they want to see in the world". This simple idea secures that the knowledge from the participating domain is represented in the prototype and vice-versa – that the challenges that the prototype may present are taken back to the specific communities of interest and resolved.

At our third workshop, which was organized at Stanford University within the Triple Helix IX international conference (whose focus was on the collaboration between university, business and government, and specifically on IT innovation as its enabler) – we pointed to systemic innovation as an emerging and necessary new trend; and as (the kind of organization represented by) knowledge federation as its enabler. Again the Engelbarts were part of our preparatory activities, and the Englishes were part of our panel as well. Our workshop was chaired by John Wilbanks – who was then the Vice President for Science in Creative Commons.

At our workshop in Barcelona, later that year, media creatives joined the forces with innovators in journalism, to create a prototype for the journalism of the future.

A series of events followed – in which the prototypes shown in Federation through Applications were created.

Knowledge Federation is a federation

Throughout its existence, and especially in this early period, Knowledge Federation was careful to make close ties with the communities of interest in its own domain, so that our own body of knowledge is not improvised or reinvented but federated. Program for the Future, Global Sensemaking, Debategraph, Induct Software... and multiple other initiatives – became in effect our federation.

After our inception workshop we paid tribute to Doug Engelbart and made close working ties with the Silicon Valley community that grew around him. Engelbart was present in the preparation for our Palo Alto workshops in 2011 and 2012, but not at the event. Bill and Roberta English, however – who were Doug's right and left hand before and during the 1968 Demo days (Bill physically created the demo) – were with us all that time.

The longer story will be told in the book Systemic Innovation (Democracy for the Third Millennium), which will be the second book in Knowledge Federation Trilogy. Meanwhile, we let our portfolio of prototypes presented in Federation through Application tell this story for us.

From the repertoire of prototypes that resulted from this collaboration (see a more complete report in Federation through Applications), we here highlight two.

The Lighthouse

It's really the model of the headlights, applied in a specific key domain.

If you imagine stray ships struggling on the rough seas of the survival of the fittest competition – then The Lighthouse is showing the way to the harbor of a whole new continent, where the way of working and existing together is collaboration, to create new systems and through them a "better world".

In the context of the systems sciences, The Lighthouse extends the conventional repertoire of a research community (conferences, articles, books...) into a whole new domain – distilling a single insight for our society at large, which is on the one hand transformative to the society, and on the other hand explains to the public why the research field is relevant to them, why it has to be given far larger prominence and attention than it has hitherto been the case.

Leadership and Systemic Innovation

Leadership and Systemic Innovation is a doctoral program that Alexander initiated at the Buenos Aires Institute of Technology in Argentina. It was later accompanied by a Systemic Innovation Lab. The program – the first of its kind – educates leaders capable of being the guides of (the transition to) systemic innovation.

As we have seen, in 1969 Erich Jantsch made a similar proposal to the MIT, but without result. Now the Argentinian MIT clone has taken the torch.