STORIES

Contents

Federation through Stories

<--

The first and most important thing you need to know is that what's being presented here is not only or even primarily an idea or a proposal or an academic result. We intend this to be an intervention into our academic and social reality. And more specifically an invitation to a conversation.

And when we say "conversation", we don't mean "just talking". The conversations we want to initiate are intended to build communication in a certain new way, both regarding the media and the manner of communicating, and regarding the themes. We use the dialog – which is a manner of speaking that sidesteps all coercion into a worldview and replaces it by genuine listening, collaboration and co-creation. By conversing in this way we also bring due attention to completely new themes. We evolve a public sphere, or a collective mind, capable of thinking new thoughts, and of developing public awareness about those themes. Here in the truest sense the medium is the message.

The details being presented are intended to ignite and prime and energize those dialogs. And at the same time evolve through those dialogs. In this way we want to prime our collective intelligence with some of the ideas of last century's giants, and then engage it to create insights about the themes that matter.

There are at least four ways in which the four detailed modules of this website can be read.

One way is to see it as a technical description or a blueprint of a new approach to knowledge (or metaphorically a lightbulb). Then you might consider

- Federation through Images as a description of the underlying principle of operation (how electricity can create light that reaches further than the light of fire)

- Federation through Stories as a description of the suitable technology (we have the energy source and the the wiring and all the rest we need)

- Federation through Application as a description of the design, and of examples of application (here's how the lightbulb may be put together, and look – it works!)

- Federation through Conversations as a business plan (here's what we can do with it to satisfy the "market needs"; and here's how we can put this on the market, and have it be used in reality

Another way is to consider four detailed modules as an Enlightenment or next Renaissance scenario. In that case you may read

- Federation through Images as describing a development analogous to the advent of science

- Federation through Stories as describing a development analogous to the printing press (which provided the very illumination by enabling the spreading of knowledge)

- Federation through Applications as describing the next Industrial and technological Revolution, a new frontier for innovation and discovery

- Federation through Conversations as describing the equivalent of the Humanism and the Renaissance (new values, interests, lifestyle...)

The third way to read is to see this whole thing as a carefully argued case for a new paradigm in knowledge work. Here the focus is on (1) reported anomalies that exist in the old paradigm and how they may be resolved in the new proposed one and (2) a new creative frontier, that every new paradigm is expected to open up. Then you may consider

- Federation through Images as a description of the fundamental anomalies and of their resolution

- Federation through Stories as a description of the anomalies in the use and development of information technology, and more generally of knowledge at large

- Federation through Applications as a description or better said of a map of the emerging creative frontier, showing – in terms of real-life prototypes what can be done and how

- Federation through Conversations as a description of societal anomalies that result from an anomalous use of knowledge – and how they may be remedied

And finally, you may consider this an application or a showcase of knowledge federation itself. Naturally, we'll apply and demonstrate some of the core technical ideas to plead our case. You may then read

- Federation through Images as a description and application of ideograms – which we've applied to render fundamental-philosophical ideas of giants accessible, and in effect create a cartoon-like introduction to a novel approach to knowledge

- Federation through Stories brings forth vignettes – which are the kind of interesting, short real-life stories one might tell to a party of friends over a glass of wine, and which enable one to "step into the shoes of a giant" or "see through his eyeglasses"

- ALT

- Federation through Applications as a portfolio of prototypes – a characteristic kind of results that suit the new approach to knowledge – which in knowledge federation serve as (1) models (showing how for ex. education or journalism may be different, who may create them and how), (2) interventions (prototypes are embedded in reality and acting upon real-life practices aiming to change them) and (3) experiments (showing us what works and what doesn't).

- Federation through Applications as a small portfolio of dialogs – by which the new approach to knowledge is put to use

Highlights

Instead of providing you an "executive summary", which would probably be too abstract for most people to follow, we now provide a few anecdotes and highlights, which – we feel – will serve better for mobilizing and directing your attention, while already extracting and sharing the very essence of this presentation. As always, we'll use the ideas of giants as 'bread crumbs' to mark the milestones in our story or argument.

</div> </div>

Social construction of truth and meaning

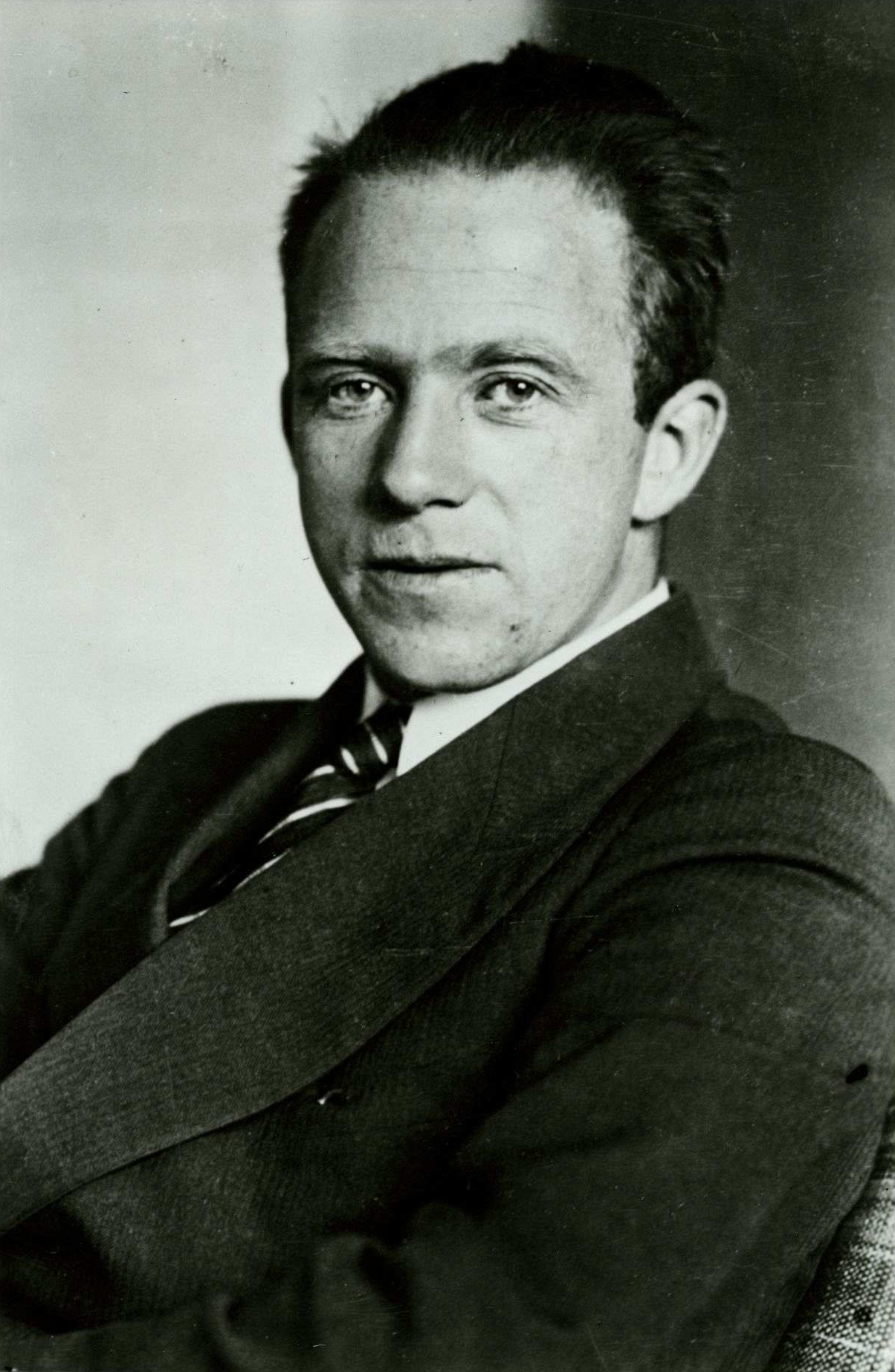

Sixty years ago, in "Physics and Philosophy", Werner Heisenberg explained how

the nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

He then pointed out how this frame of concepts was too narrow and too rigid for expressing some of the core elements of human culture – which as a result appeared to modern people as irrelevant. And how correspondingly limited and utilitarian values and worldviews became prominent. Heisenberg then explained how modern physics disproved this "narrow frame"; and concluded that

one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century.

If we now (in the spirit of systemic innovation, and the emerging paradigm) consider that the social role of the university (as institution) is to provide good knowledge and viable standards for good knowledge – then we see that just this Heisenberg's insight alone gives us an obligation – which we've failed to respond to for sixty years.

The substance of Federation through Images is to show how the fundamental insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy allow us to develop a way out of "the rigid frame" – which is a rigorously founded methodology for creating truth and meaning about any issue and at any level of generality, which we are calling polyscopy. You may understand polyscopy as an adaptation of "the scientific method" that makes it suitable for providing the kind of insights that our people and society need, or in other words for knowledge federation. In essence, polyscopy is just a generalization of the scientific approach to knowledge, based on recent scientific / philosophical insights – as we've already pointed out by talking about design epistemology, which is of course the epistemological foundation for polyscopy.

Information technology

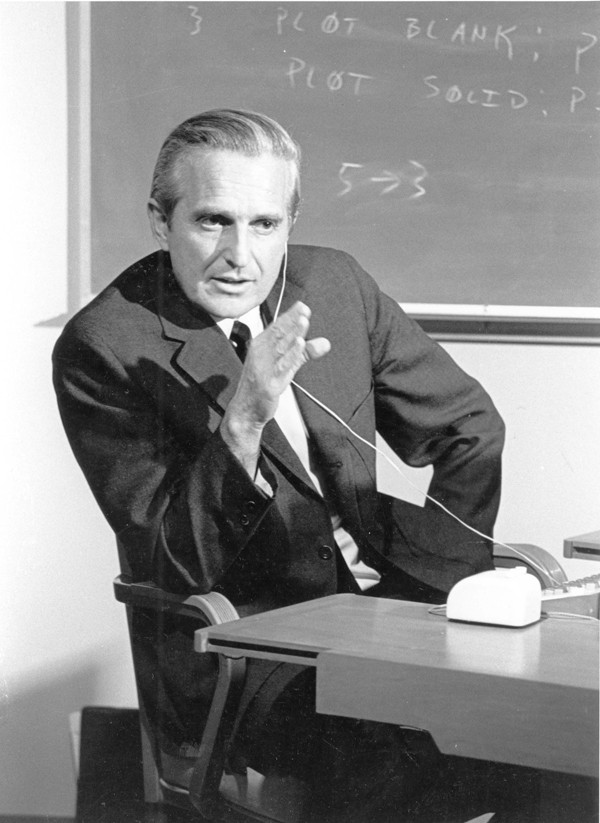

You may have also felt, when we introduced knowledge federation as 'the light bulb' that uses the new technology to illuminate the way, that we were doing gross injustice to IT innovation: Aren't we living in the Age of Information? Isn't our information technology (or in other words our civilization's 'headlights') indeed the most modern part of our civilization, the one where the largest progress has been made, the one that best characterizes our progress? In Federation through Stories we explain why this is not the case, why the candle headlights analogy works most beautifully in this pivotal domain as well – by telling the story of Douglas Engelbart, the man who conceived, developed, prototyped and demonstrated – in 1968 – the core elements of the new media technology, which is in common use. This story works on many levels, and gives us a textbook example to work with when trying to understand the emerging paradigm and the paradoxical dynamics around it (notice that we are this year celebrating the 50th anniversary of Engelbart's demo...).

These two sentences were (intended to be) the first slide of Engelbart's presentation of his vision for the future of (information-) technological innovation in 2007 at Google. We shall see that this 'new thinking' was precisely what we've been calling systemic innovation. Engelbart's insight is so central to the overall case we are presenting, that we won't resist the urge to give you the gist of it right away.Digital technology could help make this a better world. But we've also got to change our way of thinking.

The printing press analogy works, because the printing press was to a large degree the technical invention that led to the Enlightenment, by making knowledge so much more widely accessible. The question is what invention may play a similar role in the emerging next phase of our society's illumination? The answer is of course the "network-interconnected interactive digital media" – but there's a catch! Even the printing press (let it symbolize here the Industrial Age and the paradigm we want to evolve beyond) merely made what the scribes were doing more efficient. To communicate, people still needed to write and publish books, and hope that the people who needed what's written in them would find them on a book shelf. But the network-interconnected interactive digital media is a disruption of a completely new kind – it's not a broadcasting device but a "nervous system" (this metaphor is Engelbart's own); it interconnects us people in such a way that we can think together and coordinate our action, just as the cells in a sufficiently complex organism do!

To see that this is not what has happened, think about the "desktop" and the "mailbox" in your computer: The new technology has been used to implement the physical environment we've had around us – including the ways of doing things that evolved based on it. Consider the fact that in academic research we are still communicating by publishing books and articles. Haven't we indeed used the new technology to re-create 'fancy candles'.

To see the difference that makes a difference, imagine that your cells were using your own nervous systems to merely broadcast data! Think about your state of mind that would result. Then think about how this reflects upon our society's state of mind, our "collective intelligence"...

When we apply the Industrial Age efficiency thinking and values, and use the Web to merely broadcast knowledge, augment the volume, reduce the price – then the result is of course information glut. "We are drowning in information", Neil Postman observed! A completely new phase in our (social-systemic evolution) – new division, specialization and organization of the work with information, and beyond – is what's called for, and what's ahead of us.

There are in addition several points that spice up the Engelbart's history, which are the reasons why we gave it the name (in the Federation through Stories) "the incredible story of Doug):

- Engelbart saw this whole new possibility, to give our society in peril a whole new 'nervous system', already in 1951 – when there were only a handful of computers in the world, which were used solely for numerical scientific calculations (he immediately decided to dedicate his career to this cause

- Engelbart was unable to communicate his vision to the Silicon Valley – even after having been recognized as The Valley's "giant in residence" (think about Galilei in house arrest...)

So the simple conclusion we may draw from this story is that to draw real benefits from information technology, systemic innovation must replace the conventional reliance on the market. And conversely – that the contemporary information technology is an enabler of large-scale systemic change, because it's been conceived to serve that role.

Innovation and the future of the university

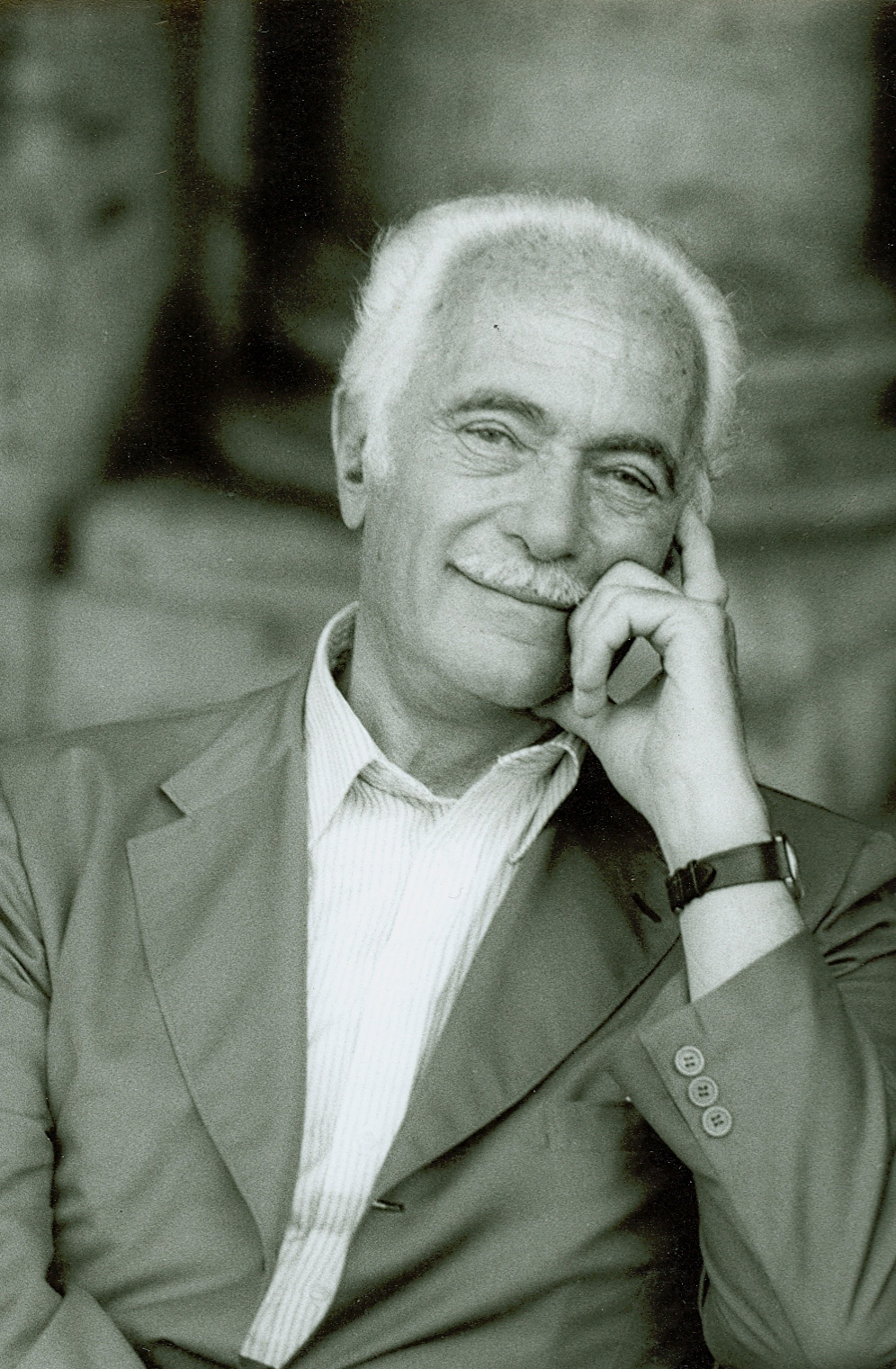

Fifty years ago Erich Jantsch made a proposal for the university of the future, and made an appeal that the university take the new leadership role which, as he saw it, was due.

[T]he university should make structural changes within itself toward a new purpose of enhancing the society’s capacity for continuous self-renewal.

Suppose the university did that. Suppose that we opened up the university to take such a leadership role. What new ways of working, results, effects... could be achieved? What might this new creative frontier look like, what might it consist of, how may it be organized?

The technique demonstrated here is the prototypes – which are the characteristic products of systemic innovation. Here's a related question to consider: If we should aim at systemic impact, if our key goal is to re-create systems including our own – then the traditional academic articles and book cannot be our only or even our main product. But what else should we do? And how?

The prototypes here serve as

- models, embodying and exhibiting systemic solutions, how the things may be put together, which may then be adapted to other situations and improved further

- interventions, because they are (by definition) embedded within real-life situations and practices, aiming to change them

- experiments, showing what works and what doesn't, and what still needs to be changed or improved

In Federation through Images we exhibit about 40 prototypes, which together compose the single central one – of the creative frontier which we are pointing to by our four mentioned main keywords. We have developed it in the manner of prospectors who have found gold and are preparing an area for large-scale mining – by building a school and a hospital and a hotel and... What exactly is to be built and how – those are the questions that those prototypes are there to answer.

In 1968 The Club of Rome was initiated, as a global think tank to study the future prospects of humanity, give recommendations and incite action. Based on the first decade of The Club's work, Aurelio Peccei – its founding president and motor power – gave this diagnosis:

The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future.

If there was any truth in Peccei's conclusion, then the challenge that history has given our generation is at the same time a historical opportunity.

The last time "a great cultural revival" happened, the "Renaissance" as we now call it, our ancestors liberated themselves from a worldview that kept them captive – where the only true happiness was to be found in the afterlife. Provided of course that one lived by the God's command, and by the command of the kings and the bishops as His earthly representatives. Is it indeed possible – and what would it take – to see our own time's prejudices and power issues in a similar way as we now see the ones that the Enlightenment liberated us from? What new worldview might help us achieve that? What new way of evolving our culture and organizing our society might we find to replace them? These, in a nutshell, are the questions taken up in Federation through Conversations.

Symbolic power and re-evolutionary politics

Another way to approach this part of our presentation is to say "Now that we've created those 'headlights' – can we use them to illuminate 'the way'? Can we see where we are headed, and find a better road to follow?" Which of course means that we must explore the way we've been evolving, as culture and as society; because that's 'the way', isn't it?

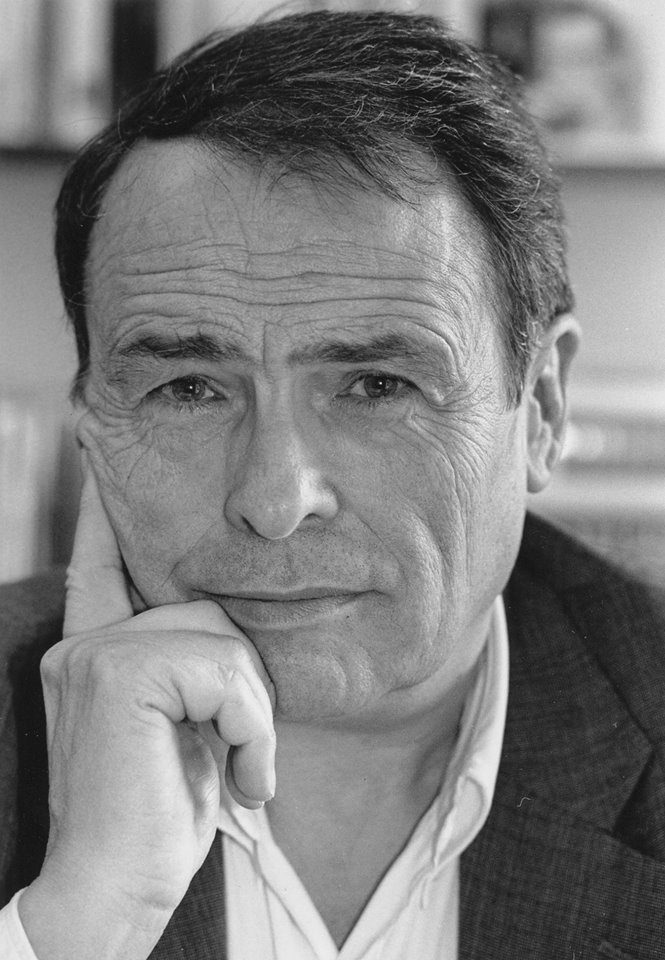

If this challenge may seem daunting, the giants again come to our rescue. Pierre Bourdieu, for one, who saw French imperialism show its true face in the war in Algeria in the late 1950s. And who, as Algeria was gaining independence, saw the old power relationship mutate and take a completely new form – so that the power was no longer in weaponry and in the instruments of torture, but in economy and the instruments of culture. This insight made Bourdieu a sociologist; he understood that the society, and the power, evolve and function in a completely different way than what we've been told.

We federate Bourdieu. We connect his insights with the insights of Antonio Damasio, the cognitive neuroscientist who discovered that we were not the rational choosers we believed we were. Damasio will help us understand why Bourdieu was so right when he talked about our worldview as doxa; and about the symbolic power which can only be exercised without anyone's awareness of its existence. We also federate Bourdieu's insights with... No, let's leave those details to Federation through Conversations, and to our very conversations.

Let's conclude here by just highlighting the point this brings us to in the case we are presenting: When this federation work has been completed, we'll not end up with another worldview that will liberate us from the old power relationships and empower us to pursue happiness well beyond what we've hitherto been able to achieve. We shall liberate ourselves from socialization into any fix worldview altogether! We'll have understood, indeed, how the worldview creation and our socialization into a fixed worldview has been the key instrument of the sort of power we now must liberate ourselves from.

In this way the circle has been closed – and we are back where we started, at epistemology as issue. We are looking at the way in which truth and meaning are socially created – which is of course what this presentation is about.

Far from being "just talking", the conversations we want to initiate build communication in a certain new way, both regarding the media used and the manner of communicating. We use the dialog – which is a manner of speaking that sidesteps all coercion into a worldview and replaces it by genuine listening, collaboration and co-creation. By conversing in this way we also bring the public attention to completely new themes. We evolve a public sphere capable of developing public awareness about those themes. Here in the truest sense the medium is the message.

Religion and pursuit of happiness

Modernity liberated us from a religious worldview, by which happiness is to be found in the afterlife (provided we do as the bishops and the kings direct us in this life). We became free to pursue happiness here and now, in this life. But what if in the process we've misunderstood bothreligion andhappiness?

It has turned out that the key meme is already there; and that it only needs to be federated. This meme also comes with an interesting story, which lets itself be rendered as a vignette.

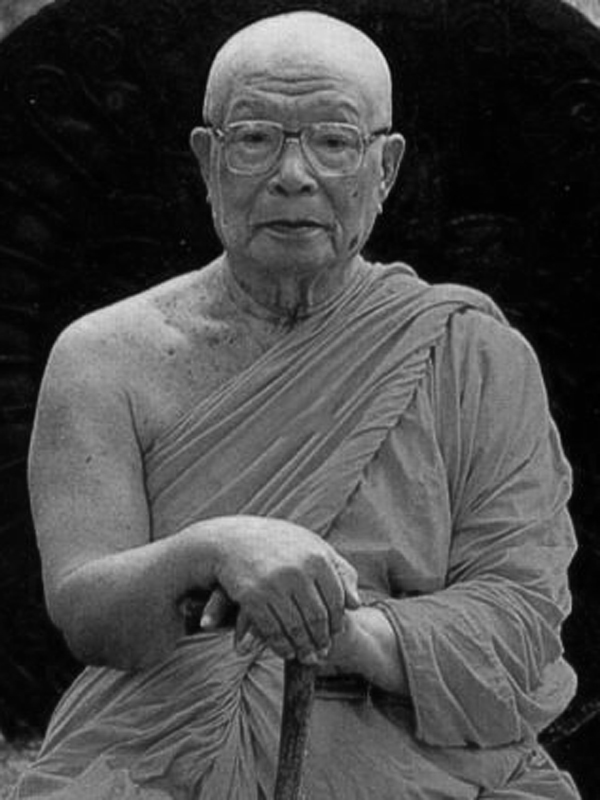

Early in the 20th century a young monk in Thailand spent a couple of years in a monastery in Bangkok and thought "This just cannot be it!" So he decided to do as the Buddha did – he went alone into a forest and experimented. He also had the original Pali scriptures with him, to help him find the original way. And reportedly he did!

What Buddhadasa ("the slave of the Buddha", as this giant of religion called himself) found out was that the essence of the Buddha's teaching was different, and in a way opposite from how Buddhism is usually understood and taught. And not only that – the practice he rediscovered is in its essential elements opposite from what's evolved as "the pursuit of happiness" in most of the modern world. Buddhadasa saw the Buddha's discovery, which he rediscovered, as a kind of a natural law, the discoveries of which have marked the inception of all major religions. Or more simply, what Buddhadasa discovered, and undertook to give to the world, was "the essence of religion".

You may of course be tempted to disqualify the Buddha's or Buddhadasa's approach to happiness as a product of some rigidly held religious belief. But the epistemological essence of Buddhadasa's teaching is that it's not only purely evidence-based or experience-based – but also that the liberation from any sort of clinging, and to clinging to beliefs in particular, is the essential part of the practice.

In the Liberation book we federate Buddhadasa's teaching about religion by (1) moving it from the domain of religion as belief to the domain of the pursuit of happiness; (2) linking this with a variety of other sources, thus producing a kind of a roadmap to happiness puzzle, and then showing how this piece snuggly fits in and completes the puzzle; (3) showing how religions – once this meme was discovered – tended to become instruments of negative socialization; and how we may now do better, and need to do better.

Knowledge federation dialog

Finally, we need to talk about our prototype, about knowledge federation. While this conversation will complete the prototype (by creating a feedback loop with the help of which it will evolve further), the real theme and interest of this conversation is of course well beyond what our little model might suggest.

In the midst of all our various evolutionary mishaps and misdirections, there's at least this one thing that has been done right – the academic tenure. And the ethos of academic freedom it institutionalized. What we now have amounts to a global army, of people who've been selected and trained and publicly sponsored to think freely. If our core task is a fresh new evolutionary start – beyond "the survival of the fittest" and the power structures it has shackled us with – then it's hard to even imagine how this could be done without engaging in some suitable way this crucially important resource.

How are we using it?