STORIES

Contents

Federation through Stories

Pragmatics of an emerging paradigm

innovation for sustainability

We look at the emerging paradigm, as modeled by knowledge federation, from a pragmatic point of view. We have the global issues; and we have the information technology, and innovation in general. How can we inform their future course? We have already seen some of that, of course. But here we approach this most interesting theme by sharing the insights of giants who originated them. Two of them – and we begin our journey by telling their stories – are especially important for us, as progenitors and icons of the two core sides of our initiatives. Douglas Engelbart is introduced here as the icon of knowledge federation; Erich Jantsch is introduced as the icon of systemic innovation. We shall then weave their stories together. Something most interesting will result.

Vignettes

How to lift up an idea from undeserved anonymity

We tell vignettes – engaging, lively, catchy, sticky... real-life people and situation stories, to distill the core ideas of the most daring thinkers from the vocabulary of their field, and to give them the power of impact. We then show how to join the vignettes together into threads, and threads into patterns and patterns into a gestalt – an overarching view of our situation, which shows how the situation may (need to) be handled.

While it is the ideas that lead to the gestalt, it is the gestalt that gives the ideas their relevance, and their deeper reason for existence.

The incredible history of Doug

The 21st century printing press

Of course it's the Web – but...

The printing press is a suitable metaphor and a point of departure for us, because of its central role in the emergence of the last big societal paradigm shift. Indeed, Gutenberg's has often been credited for the spreading of knowledge that resulted in the Enlightenment, and all the other related transformations. What might play a similar role today? The story told next will highlight some of the main points in a palpable and vivid way.

His epiphany

Having decided, as a novice engineer in December of 1950, to direct his career so as to maximize its benefits to the mankind, Douglas Engelbart thought intensely for three months about the best way to do that. Then he had an epiphany.

On a convention of computer professionals in 1968 Engelbart and his SRI-based lab demonstrated the computer technology we are using today – computers linked together into a network, people interacting with computers via video terminals and a mouse and windows – and through them with one another.

In the 1990s it was finally understood, or in any case some people understood, that it was not Steve Jobs and Bill Gates who invented the technology, or even the XEROS PARC from which they took it. Engelbart received all imaginable honors that an inventor can receive. Yet he made it clear, and everyone around him knew, that he felt celebrated for a wrong reason. And that the gist of his vision had not yet been understood, or put to use. "Engelbart's unfinished revolution" was coined as the theme for the 1998 Stanford University celebration of his Demo. And it stuck.

The man whose ideas created "the revolution in the Valley" passed away in 2013 – feeling that he had failed.

Engelbart's unfinished revolution

What did Engelbart see in his vision, and pursued so passionately throughout his long career? Why was this vision not understood?

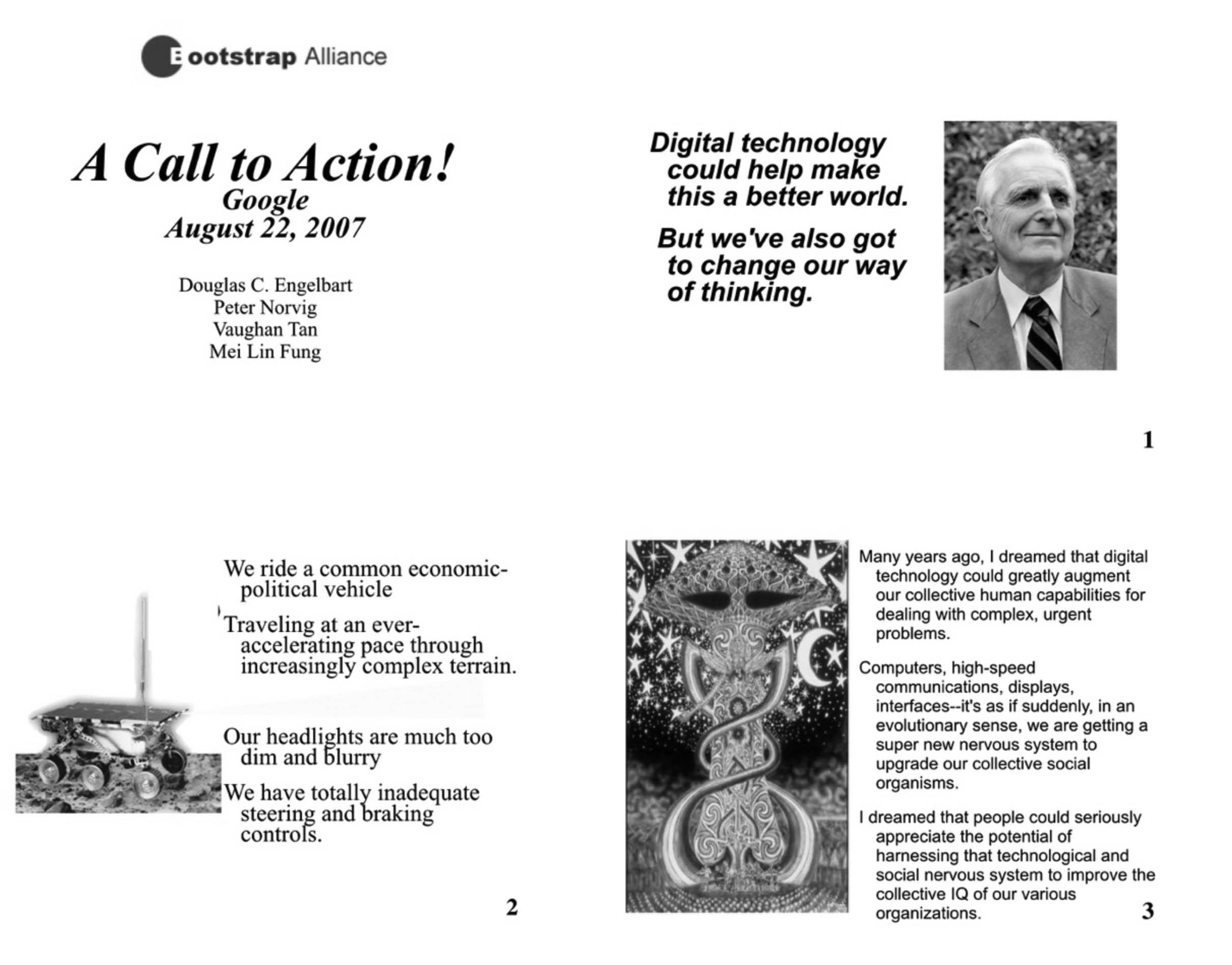

It seems best to introduce it by another anecdote, and – if not by his own words, then at least by his own Powerpoint slides. Here they are.

Around that time Engelbart was diagnosed as having Alsheimer's disease, and it was clear hat his career was coming to an end. The title he choose for his presentation should make it clear that what he wanted to give to Google, and to the world, was a direction call to pursue it.

The first slide makes it clear that a large and unfulfilled opportunity has remained in digital technology. To realize it, we must change the way we think.

The second slide specifies what exactly that new thinking might be. The message is so closely similar to the message of our Modernity ideogram (see Federation through Images), that we only need to point to our explanation there. But there is also a word for this way of thinking; and the word is "systemic".

The third slide then is his, and our, main point. Why is systemic thinking necessary if the digital technology should give us the benefits that it has in store for us?

The slide has three points, explaining his "dream". The first says that "digital technology could greatly augment the human capabilities for dealing with complex, urgent problems". So imagine once again Doug as an idealistic novice engineer, barely 25 years old, thinking about how best to contribute to the world. He has realized that the humanity has problems it doesn't know how to solve, whose "complexity times urgency" factor is growing at an accelerated speed or "exponentially".

The second point links the familiar digital computer infrastructure – the machine, the high-speed network, the interactive interface – with "super new nervous system". We'll come back to that. For now just notice that the "super new nervous system" is precisely what we now do have.

The third point begins again with the word "dream", suggesting that what follows truly remained just a dream. So what was the unfulfilled part of his dream? 'That people could seriously appreciate the potential of harnessing that technological and social nervous system to improve the collective IQ of our various organizations." To Doug "the collective IQ" meant the collective capability to deal with "complexity times urgency".

To see his really central point, imagine the humanity as a large organism. It has lately grown extremely ("exponentially") fast in both size and power. It has also lately gotten a whole new nervous system. The future of this organism, Doug suggested, will crucially depend on his ability to learn to coordinate the actions of his various organs by taking advantage of this nervous system. To see what's missing, imagine the organism going toward a wall. Imagine that the eyes of the organism see that, but are trying to communicate it to the brain by writing academic articles in some specialized academic field of interest.

Doug's big point

The point here, the really big and central one, is that to take advantage of the "technological and social nervous system", the "cells" in that system (namely we, the people) need to specialize and divide our knowledge-work labor in entirely different ways than what was possible without the "nervous system".

However big a disruption it was, the printing press could only vastly speed up the copying of manuscripts, which the monks in the monasteries were already doing.

When the new technology is applied in that way, the result is, of course what we've been talking all along. To understand still more closely what's missing, think of all the cells in the gigantic organism trying to communicate with one another by merely using the "super new nervous system" to merely broadcast messages!

You will now easily notice that what's missing is quite exactly what we are calling knowledge federation. And indeed, as we shall see in more detail below, our initiative has largely been inspired and oriented by Engelbart's vision.

The incredible part

You might now rightly wonder – what's really so incredible in this history of Doug?

To see it, think about a brilliant mind saying, in all clarity, "this is what the humanity must do to solve its problems and evolve further!" Imagine him using his best efforts to first of all become able to do that, and then actually producing the enabling technology. Imagine us the people using this technology to only speed up immensely what we were already doing. Think about the Silicon Valley failing to understand, or even hear, its genius in residence – even after having recognized him as that! Think that to really understand Doug's various technical contributions, one really must see them in the context of his larger vision. Imagine that the first four slides, which define this vision, were not even shown at the 2007 presentation at Google! If you Google it, you will find that Doug is introduced as "the inventor of the computer mouse". And that there is no mention, really, of "a call to action"!

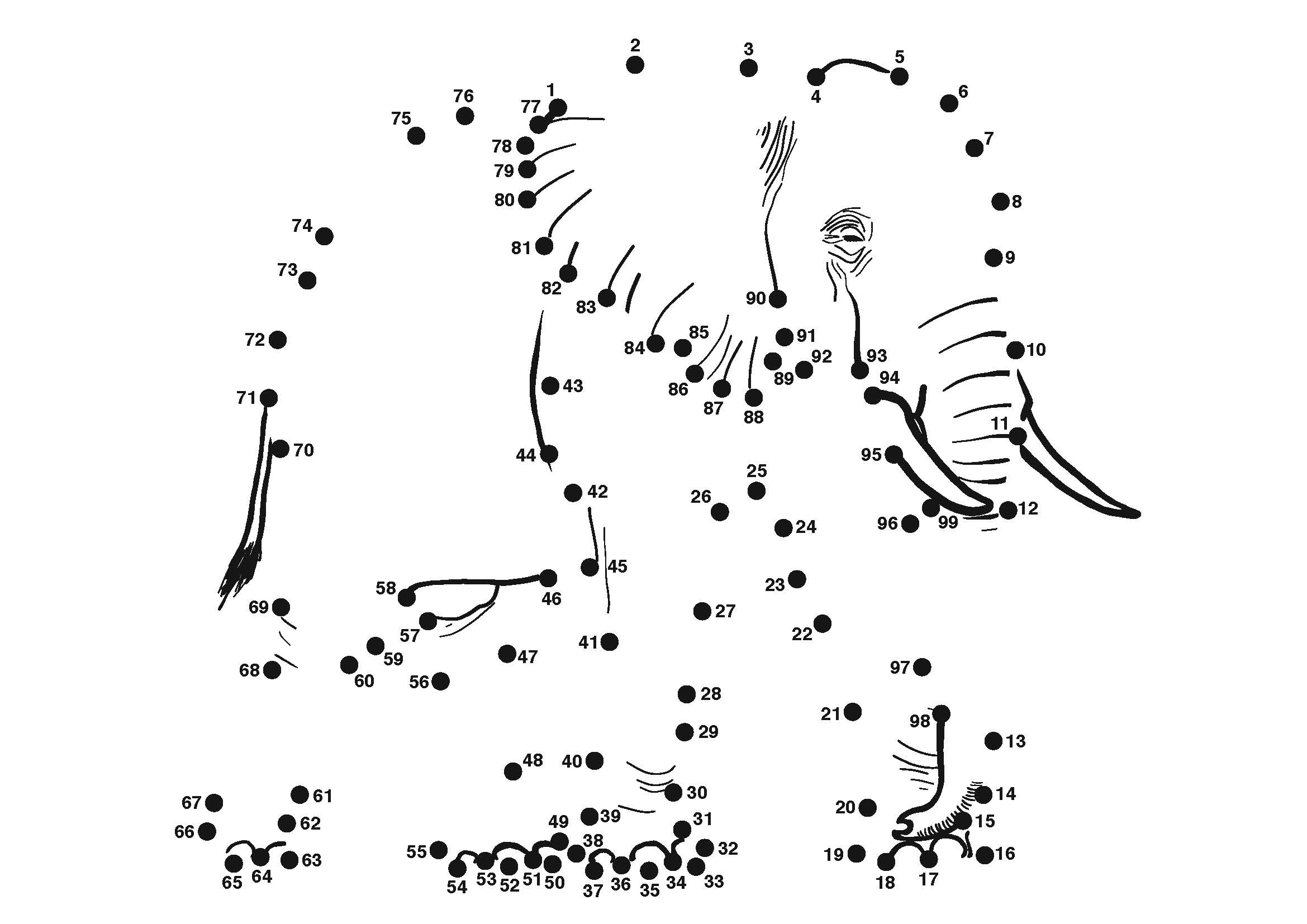

The invisible elephant

Here is how we offer to characterize the situation just described.

Every time Engelbart was present in a room talking, or being celebrated, there was also an elephant in the room. Imagine a huge animal, in the midst of a large university auditorium – should this not be a first-rate sensation? But alas – the elephant was invisible; or better said – nobody saw it except Doug!

We use this metaphor, of an invisible elephant, to point to the emerging paradigm. We talk about the giants as seeing the elephant each from its own perspective (the ear as a fan, the trunk as a hose, the tail as a rope...). They are excited by the awesome sight, and they try to communicate it to the others. But alas – this animal is something nobody has ever seen! And there is really no name for it, not to speak about naming its various parts or organs. And so our giants appear to be talking about all kinds of different things – yet those things will truly make sense only when seen in the context of the paradigm. Just as the bodily parts of an elephant can be understood as functional elements of the whole big thing.

And so what we've undertaken to do is to 'connect the dots'. Show the 'elephant'. Then it will all be crystal clear!

Wiener's paradox

The science behind sustainability

Doug's seemingly innocent metaphor, his "vehicle" on Slide 2, turns out to have a deeper and quite technical meaning. If you know even even just a bit about cybernetics, then you might recognize in Doug's metaphor the "feedback and control", that are there household terms. Just as the bus must have functioning headlights and steering and breaking controls, so must any system have suitable feedback (information inflow, and use) and control (a way to apply the incoming information to correct its course, or more generally behavior) – if it is to be "viable" or "stable" or "functional" or "sustainable".

The science behind democracy

But we could have just as well talked about