Difference between revisions of "STORIES"

m |

m |

||

| Line 272: | Line 272: | ||

<div class="col-md-7"><h2>Holoscope</h2> | <div class="col-md-7"><h2>Holoscope</h2> | ||

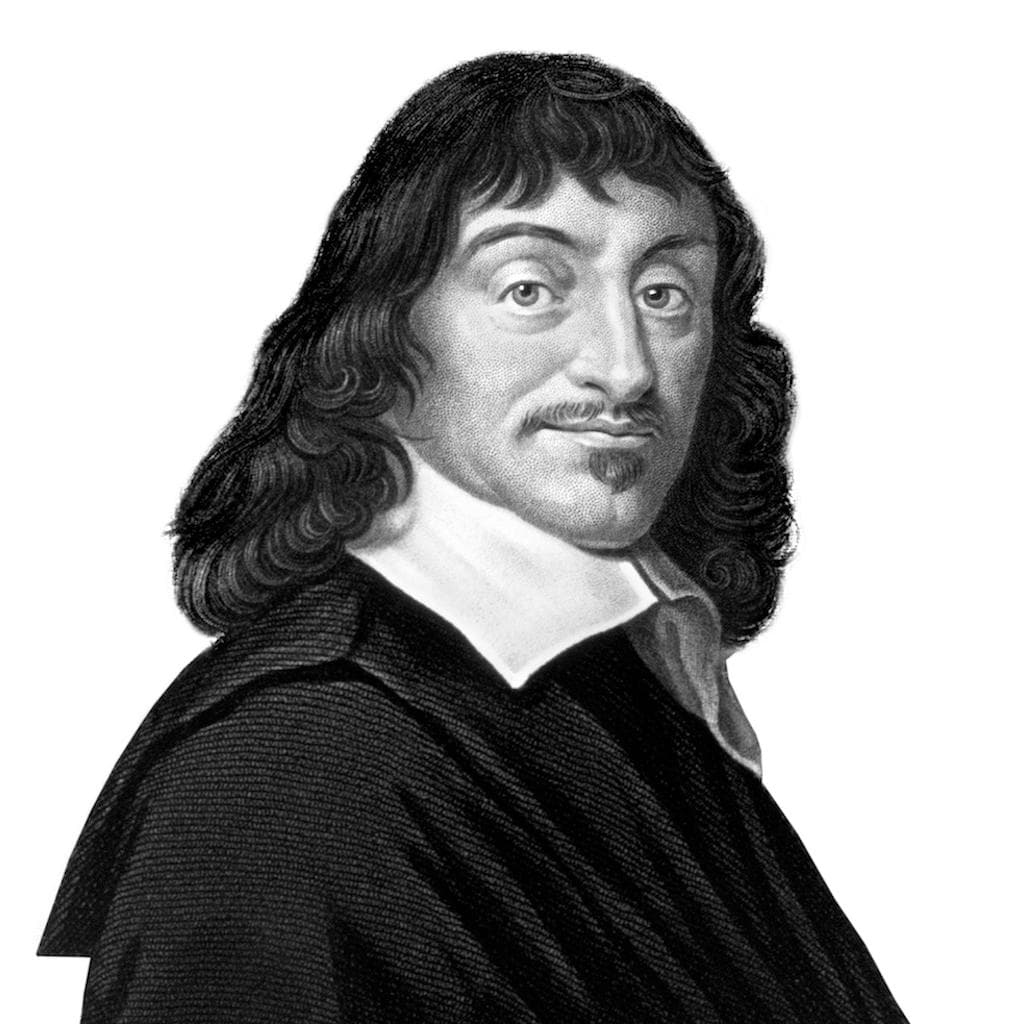

<p>René Descartes pointed out in his testament, his unfinished <em>Règles pour la direction de l’esprit</em> (Rules for the Direction of the Mind)—as Rule One: “The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it bears solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.” And pointed to academic specialization as <em>the</em> impediment to practicing Rule One: “In truth, it surprises me that almost everyone studies with greatest care the customs of men, the properties of the plants, the movements of the planets, the transformations of metals and other similar objects of study, while almost nobody reflects about sound judgment or about this universal wisdom, while all the other things need to be appreciated less for themselves than because they have a certain relationship to it. It is then not without reason that we pose this rule as the first among all, because nothing removes us further from the seeking of truth, than to orient our studies not towards this general goal, but towards the particular ones.”</p> | <p>René Descartes pointed out in his testament, his unfinished <em>Règles pour la direction de l’esprit</em> (Rules for the Direction of the Mind)—as Rule One: “The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it bears solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.” And pointed to academic specialization as <em>the</em> impediment to practicing Rule One: “In truth, it surprises me that almost everyone studies with greatest care the customs of men, the properties of the plants, the movements of the planets, the transformations of metals and other similar objects of study, while almost nobody reflects about sound judgment or about this universal wisdom, while all the other things need to be appreciated less for themselves than because they have a certain relationship to it. It is then not without reason that we pose this rule as the first among all, because nothing removes us further from the seeking of truth, than to orient our studies not towards this general goal, but towards the particular ones.”</p> | ||

| − | <h3>I | + | <h3>I will now summarize my case for correcting the fundamental error we've been talking about.</h3> |

| − | <p>The | + | <p>And then show you how <em>transdisciplinarity</em> follows as a consequence.</p> |

| − | + | <h3>We have seen four independent arguments.</h3> | |

| − | + | <p>The first and most obvious one is pragmatic: <em><b>Correct</b></em> or "right" <em><b>information</b></em> (which is now our vital need) is to the <em><b>information</b></em> we have as the lightbulb is to the candle.</p> | |

| + | <p>The second is <em><b>ontological</b></em>: The <em><b>information</b></em> we have is <em>not</em> justifiable on <em><b>ontological</b></em> grounds; <em><b>transdisciplinarity</b></em> gives us a way to correct the reported <em>fundamental</em> anomalies.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The third argument is political-ethical: <em><b>Reification</b></em> as <em><b>foundation</b></em> is (for all we <em><b>know</b></em>) an instrument of <em><b>power structure</b></em>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The fourth is the IT-argument: We must develop <em><b>information</b></em> on a <em><b>pragmatic</b></em> foundation because, as the things are now, we use the powerful new information technology to shoot ourselves in the foot.</p> | ||

<p>You will now easily comprehend <em>how</em> I am proposing to correct the fundamental error we've been talking about; and how we may unravel and reverse the unsustainabilities in global trends and the discontinuities in cultural evolution by doing that; and why instituting <em><b>transdisciplinarity</b></em>, as operationalized by <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>, is the practical way to achieve all that. The explanation is in the bottom three <em><b>points</b></em> of the Holotopia ideogram; and in the way they are related.</p> | <p>You will now easily comprehend <em>how</em> I am proposing to correct the fundamental error we've been talking about; and how we may unravel and reverse the unsustainabilities in global trends and the discontinuities in cultural evolution by doing that; and why instituting <em><b>transdisciplinarity</b></em>, as operationalized by <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>, is the practical way to achieve all that. The explanation is in the bottom three <em><b>points</b></em> of the Holotopia ideogram; and in the way they are related.</p> | ||

<h3>Our most powerful asset is their <em>synergy</em>.</h3> | <h3>Our most powerful asset is their <em>synergy</em>.</h3> | ||

Revision as of 16:48, 1 January 2024

Contents

- 1 Federation through Keywords

- 1.1 Truth by convention gives us a way to create an independent reference system.

- 1.2 Keywords are concepts defined by convention.

- 1.3 Reification is the traditional approach to communication.

- 1.4 Keyword creation is a form for linguistic and institutional recycling.

- 1.5 Keywords enable us to "stand on the shoulders of giants" and see further.

- 1.6 Paradigm

- 1.7

- 1.8 Logos

- 1.9

- 1.10

- 1.11 Materialism

- 1.11.1 In materialism, (direct experience of, and mechanistic-comprehension of) "material reality" serves as reference system.

- 1.11.2 In materialism "success" (what works in practice) is used for orientation.

- 1.11.3 "Convenience"—reaching out toward what feels attractive—is materialism's "core value".

- 1.11.4 Once again the (evolution of) academic tradition, and the human mind, must be liberated.

- 1.11.5 Transdisciplinarity and holotopia are conceived as steps toward liberating our next generation from the world.

- 1.12

- 1.13 Design epistemology

- 1.13.1 And because the foundation we have is not a one on which the cultural evolution can continue.

- 1.13.2 People began to believe that science (not the Bible) was the right way to truth.

- 1.13.3 So what is to be done?

- 1.13.4 Design epistemology turns Einstein's "epistemological credo" into a convention.

- 1.13.5 Design epistemology as foundation is broad.

- 1.13.6 Design epistemology as foundation is also solid.

- 1.14

- 1.15

- 1.16 Polyscopic methodology

- 1.17

- 1.18

- 1.19 Convenience paradox

- 1.20

- 1.21

- 1.22 Knowledge federation

- 1.23

- 1.24

- 1.25 Systemic innovation

- 1.26

- 1.27

- 1.28 Power structure

- 1.29

- 1.30

- 1.31 Holoscope

- 1.32

- 1.33 Holotopia

- 1.33.1 What are those "things" we need to make whole?

- 1.33.2 The point of it all is that those two realms of improvement opportunities depend on each other.

- 1.33.3 I let the holotopia principle point, by its simplicity, to the difference that transdisciplinarity will make.

- 1.33.4 Only science can achieve that.

- 1.33.5 How suitable is their system for this all-important role?

- 1.34

- 1.35 Dialog

- 1.36

Federation through Keywords

(Ulrich Beck, The Risk Society and Beyond, 2000)

To orient ourselves in the "post-traditional world" (where traditional recipes no longer work), to step beyond the "risk society" (where existential risks lurk in the dark, because we can neither comprehend nor resolve them by thinking as we did when we created them)—we must create new ways to think and speak; but how?

Here a technical idea—truth by convention—is key; I adopted it or more precisely federated it from Willard Van Orman Quine; who qualified the transition to "truth by convention" as a sign of maturing that the sciences have manifested in their evolution; so why not use it to mature our pursuit of knowledge in general? Truth by convention is the notion of truth that is usual in mathematics: Let x be... then... It is meaningless to argue whether x "really is" as defined.

Truth by convention gives us a way to create an independent reference system.

Independent, that is, from the beliefs of our traditions; and from the social "reality" or the world we live in. Truth by convention empowers us to (create information that makes it possible to) reflect about them critically.

Keywords are concepts defined by convention.

Years ago, when this work was still in infancy and before I read about guided evolution of society, I coined a pair of keywords—tradition and design—to explain the nature of the error I am inviting you to correct; the one the Modernity ideogram is pointing to. Tradition and design are two ways of thinking and being in the world; and two distinct ways of evolving culturally and socially—corresponding to the two ways in which wholeness can result: Tradition relies on spontaneous evolution (where things are adjusted to each other through many generations of use); design relies on accountability and deliberate action. Design means thinking and acting as a designer would, when designing a technical object such as a car; and making sure that the result is functional (it can take people places), and also safe, affordable, appealing etc. The point of this definition is that when tradition can no longer be relied on—design must be used.

So let us right away take a decisive step toward the design thinking and being by turning "reification" into a keyword; and explain that reification is something the traditional cultures did and had to do (to compel everyone to comply to the traditional order of things without needing to understand it); and use the Modernity ideogram to explain why we must learn to avoid reification (because it hinders us from designing i.e. from deliberately seeing things whole and making things whole).

You may now understand the error I am inviting you to correct as something (only) the traditional people could have made; and the Modernity ideogram as depicting a point of transition: We are no longer traditional; and we are not yet designing; we live in a (still haphazard) transition from one stable way of evolving and being in the world, which is no longer functioning—and another one, which is not yet in place.

Reification is the traditional approach to communication.

And to concept definition in particular. See the approach to concept definition I have just introduced as a way or the way to avoid reification.

When I define for instance "culture" by convention, and turn it into a keyword, I am not saying what culture "really is"; I am creating a way of looking at an endlessly complex real thing—and projecting it, as it were, onto some judiciously chosen plane; so that we may talk about it and comprehend it in simple and clear terms, by seeing it from a specific angle; and I'm inviting you, the reader, to see culture as it's been defined.

Defined by convention, institutions like "science" or "religion" are not reified as what they currently are—but defined as means to an end i.e. in terms of a certain specific function or a collection of functions in the system of society; so that we may adapt the actual institutions to those functions.

Keyword creation is a form for linguistic and institutional recycling.

Often but not always, keywords are adopted from the repertoire of a frontier thinker, an academic field or a cultural tradition; they then enable us to federate what's been comprehended or experienced in some of our culture's dislodged compartments.

Keywords enable us to "stand on the shoulders of giants" and see further.

Paradigm

I use the keyword paradigm informally, to point to a societal and cultural order of things as a whole; and to explain the strategy for solving "the huge problems now confronting us" and continuing cultural evolution I am proposing to implement—which is to enable the paradigm to change; from the one we presently live in, which I'll characterize as materialism—all the way to holotopia.

I use the keyword elephant as a nickname for holotopia when I want to be even more informal—and highlight that it's a coherent order of things where everything depends on everything else, as the organs of an elephant do.

I also use elephant as metaphor and keyword to motivate the strategy I have just mentioned by pointing to a paradox: Paradigms resist change; you just can't fit an elephant's ear onto a mouse! And yet comprehensive change, of a paradigm as a whole, can be natural and effortless—when the conditions for it are ripe.

We live in such a time.

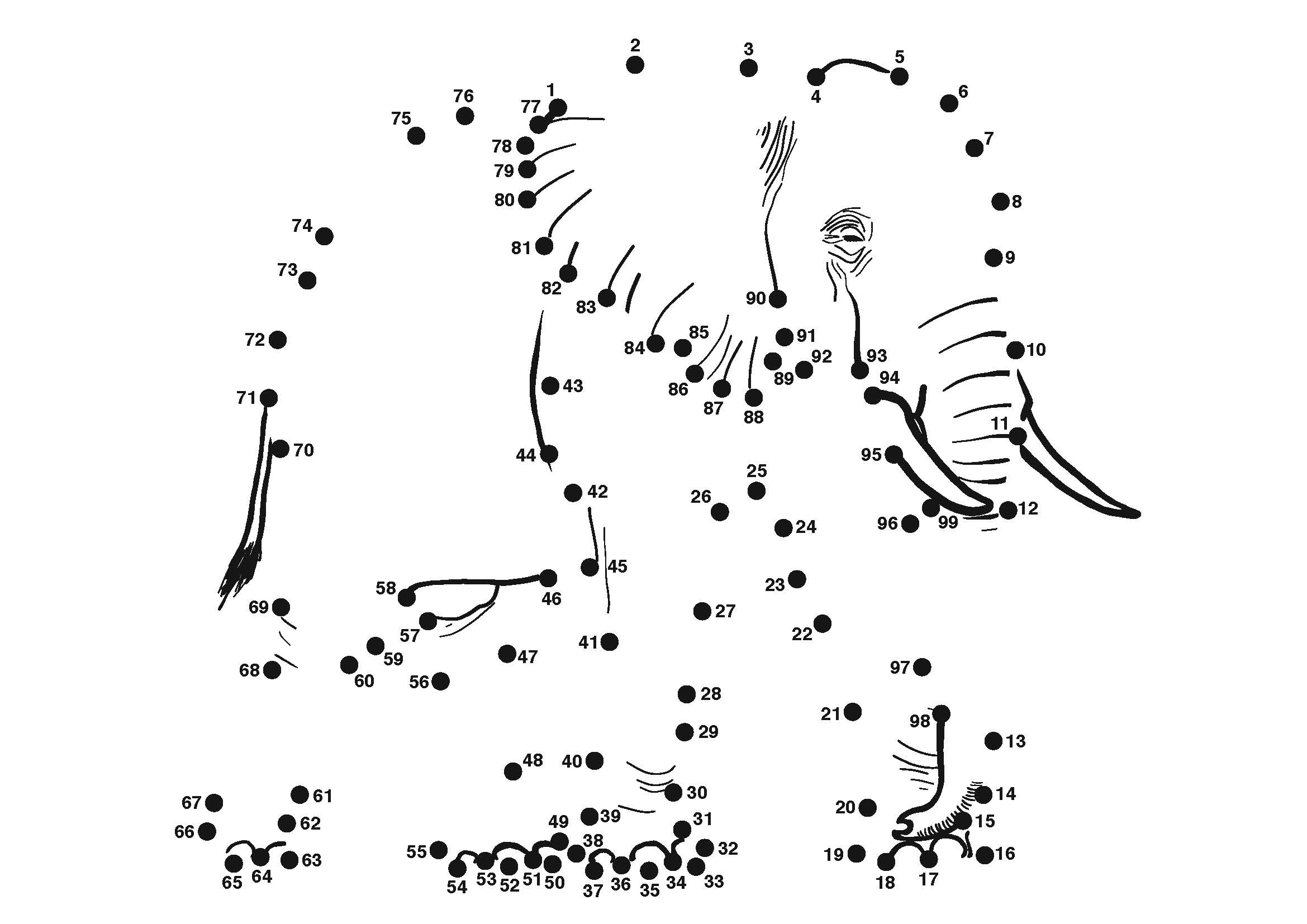

When all the data points that are needed for constituting an entirely different paradigm are already there; so that all that remains is—to connect the dots; or more accurately—to restore our collective capability to connect the dots.

Which is what knowledge federation proposal is all about.

The elephant was in the room when the 20th century’s giants wrote or spoke; but we failed to see him because of the jungleness of our information; and because of disciplinary and cultural fragmentation; and because our thinking and communication are still as the traditions shaped them. We heard the giants talk about a ‘thick snake’, a ‘fan’, a ‘tree-trunk’ and a ‘rope’, often in Greek or Latin; they didn’t make sense and we ignored them. How differently our information fares when we understand that it was the ‘trunk’, the ‘ear’, the ‘leg’ and the ‘tail’ of a vast exotic ‘animal’ they were talking about; whose very existence we ignore!

Transdisciplinarity, as prototyped by knowledge federation is also a paradigm—in information; which will empower us to connect the dots and manifest the comprehensive paradigm. You may now comprehend this call to action (to institute transdisciplinarity or knowledge federation academically) as a call to mobilize the power that our society has invested in science and in the university institution at large—to design the process and be the process by which the society's 'candle headlights' will be turned into the real thing. This process must be designed because no matter how hard we try—we'll never create the lightbulb by incrementally improving the candle. To substitute 'the lightbulb' for 'the candle' we must design a suitable process; which (a moment of thought might be necessary to see why) will have to include a prototype.

Knowledge federation is both the process and the prototype.

Science enabled the existing paradigm to come about; transdisciplinarity must be in place to enable us to transition to the next one.

I use the keyword paradigm also more formally, as Thomas Kuhn did—to point to

- a different way to conceive a domain of interest, which

- resolves the reported anomalies and

- opens a new frontier to research and development.

Only here the domain of interest is not a conventional academic field, where paradigm changes have been relatively common—but information and knowledge and cultural evolution at large.

In what follows I will structure my case for transdisciplinarity alias knowledge federation as a paradigm proposal—i.e. as a reconception of information and other categories on which our evolutionary course depends; and show how this reconception enables us to resolve the anomalies that thwart our efforts to comprehend and handle the core or pivotal themes of our lives and times; and how those anomalies are resolved by the proposed approach; and how this reconception opens up a creative frontier closely similar to the one that began to blossom after Galilei's and Descartes' time—where the next-generation scientists will be empowered to be creative in ways and degrees as the founders of Scientific Revolution were creative; and as the condition of their world will necessitate.

– Some years ago I was struck by the large number of falsehoods that I had accepted as true in my childhood, and by the highly doubtful nature of the whole edifice that I had subsequently based on them. I realized that it was necessary, once in the course of my life, to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations if I wanted to establish anything at all in the sciences that was stable and likely to last.

(René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, 1641)

Logos

The Liberation book opens with the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest—at the point in humanity's evolution when a sweeping paradigm shift was about to take place; the book then draws a parallel between that moment in history and the time we live in. So let me right away turn "mind" into a keyword; and use it to point out that liberating the way we use the mind and allowing it to change is—and has always been—the way to enable the paradigm to change; or the way to change course. I give the keyword mind a more general meaning meaning than this word usually has; closer to its French cognate "esprit", as Descartes used it in the title of his unfinished work Règles pour la direction de l'esprit (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). Indeed (as I pointed out in Liberation book's ninth chapter, which has "Liberation of Science" as title)—the course of action I am proposing can be seen as the "it's about time" continuation of Descartes' all-important project.

Transdisciplinarity, as prototyped by knowledge federation, is envisioned as a liberated academic space where the next-generation scientists will be empowered to be creative in ways as Galilei and Descartes were creative—and "start again right from the foundations"; and design the way(s) they do science (instead of blindly inheriting them from tradition).

I also coin logos as keyword; and erect is as banner demarcating this frontier, and inviting to the next scientific revolution; where we'll again liberate the mind (from compliance to "logic" as fixed and eternal "right" way to think; and from the suffix "logy" which we use to name scientific disciplines—and suggest that they embody logos; and compel us to comply to the hereditary procedures they embody). Logos as 'banner' invites (next-generation) scientists to revive an age-old quest—for the correct way to use the mind; by pointing to its historicity (i.e. that it did change in the past and will change again).

"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and logos was God." To Hellenic thinkers logos was the principle according to which God organized the world; which makes it possible to us humans to comprehend the world correctly—provided we align with it the way we use our minds. How exactly we may achieve that—there the opinions differed; and gave rise to a multitude of philosophical schools and traditions.

But "logos" faired poorly in the post-Hellenic world; neither Latin nor the modern languages offered a suitable translation. For about a millennium our European ancestors believed that logos had been revealed to us humans by God's own son; and considered questioning that to be the deadly sin of pride, and a heresy.

The scientific revolution unfolded as a reaction to earlier theological or "teleological" explanations of natural phenomena; as Noam Chomsky pointed out in his University of Oslo talk "The machine, the ghost, and the limits of understanding", its founders insisted that a "scientific" explanation must not rely on a 'ghost' acting within 'the machine'; that the natural phenomena must be explained in ways that are completely comprehensible to the mind—as one would explain the functioning of a clockwork.

Initially, science and church or tradition coexisted side by side—the latter providing the know-what and the former the know-how; but then right around mid-19th century, when Darwin stepped on the scene, the way to use the mind that science brought along discredited the mindset of tradition; and it appeared to educated masses that science was the answer; that science was the right way to knowledge.

So here is my point—what I wanted to tell you by reviving this old word, and restoring it to function: The way we use the mind today—on which materialism grew—has not been chosen on pragmatic grounds; indeed it has not been chosen at all—but simply adopted or adapted from what people saw as "scientific" way to think; in the 19th century, when the educated masses abandoned the belief that logos was revealed and recorded once and for all in the Bible. And it was by this same sequence of historical accidents that science (which had been developed for an entirely different purpose—to unravel the mechanisms of nature) ended up in the the much larger role of "Grand Revelatory of modern Western culture" as Benjamin Lee Whorf branded it in Language, truth and reality.

That's how we ended up with 'candles' as 'headlights'.

– The Matrix is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

(Morpheus to Neo, The Matrix.)

Materialism

Before we turn to holotopia, let's take a moment and theorize our present paradigm. What I'm calling materialism is not an actual but a theoretical or "ideal" order of things—which follows as consequence of the cultural–fundamental coup I've just described; where the traditional ideas and ideals (which, while far from perfect, used to provide people know-what) have been abandoned, and a proper replacement has not yet been found or even sought for. Here's the gist of it, in a nutshell, and I'll put it crudely: I acquire some material thing and this gives me a pleasurable feeling; and I interpret what happened in causal terms—and see the acquisition as cause and the gratifying feeling as its consequence; and I conceive my "pursuit of happiness" accordingly.

See materialism's way to use the mind as a travesty of science; and materialism itself as the cultural and social order of things that follows from its consistent application—where (a certain causal clockwork-like comprehension of) "the material world" is used as a measure of all things; where the direct experience of the material world, what feels attractive or unattractive, is presumed to be an experimental fact of sorts and promoted to the status of "interests" or "needs"; and allowed to determine or to be our know-what—so that all that remains is technical know-how; the knowledge of how to acquire what we want or need; by competing Darwin-style within systems conceived as a "fair" or "zero-sum" games.

In materialism, (direct experience of, and mechanistic-comprehension of) "material reality" serves as reference system.

Anthony Giddens wrote in Modernity and Self-Identity) in 1991: “The threat of personal meaninglessness is ordinarily held at bay because routinised activities, in combination with basic trust, sustain ontological security. Potentially disturbing existential questions are defused by the controlled nature of day-to-day activities within internally referential systems. Mastery, in other words, substitutes for morality; to be able to control one’s life circumstances, colonise the future with some degree of success and live within the parameters of internally referential systems can, in many circumstances, allow the social and natural framework of things to seem a secure grounding for life activities.”

In materialism "success" (what works in practice) is used for orientation.

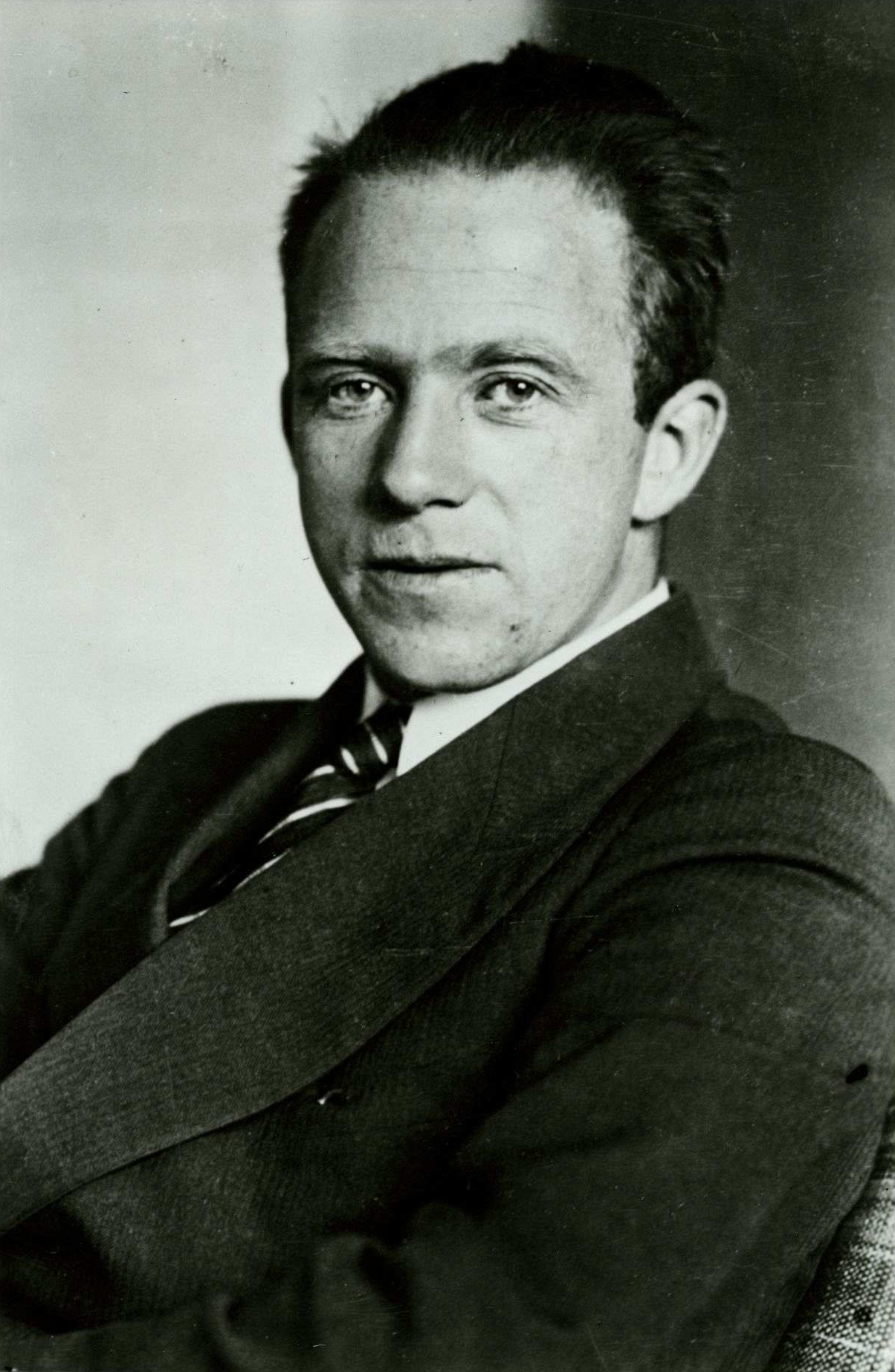

"Mind could be introduced into the general picture only as a kind of mirror of the material world", Werner Heisenberg wrote in Physics ad Philosophy. Not having any guiding ideas or principles, in materialism people use direct experience or convenience to make choices; they simply this complex and pivotal matter by reifying the way they experience the material world; they reify their wants as their "needs". The rest is then just the matter of know-how—of how to acquire the material things one "needs".

"Convenience"—reaching out toward what feels attractive—is materialism's "core value".

Which follows from its characteristic way to use the mind (whereby only "the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided" are considered as possible or relevant or "real", as Heisenberg pointed out)–and considers those things and only those things that appear attractive to our senses as real and worth pursuing (technical science here won't be of much help); and in this way decides or circumvents the larger issue of know-what, so that know-how (how to acquire the things we "need") is all that remains.

"Doxa" is the keyword that Pierre Bourdieu used (he adopted it from Max Weber, but its usage dates as far back as Aristotle) to point to corresponding phenomenology: The more familiar word "orthodoxy" means believing that one's own worldview or paradigm is the only "right" one; doxa ignores even the existence of alternatives; it means believing that the existing social reality is in a similar way immutable and real as the physical world is. You may comprehend doxa as an addiction—which results when the mind's adaptive function (which evolved to help us adapt and function in the natural world) is applied so that the social world is experienced as "the reality" to which we must adapt. In Liberation book's Chapter Nine I point out how Socrates demonstrated that we humans tend to be victims of doxa and have belief instead of knowledge; and how Plato instituted the Academia to help his fellow humans evolve knowledge-based, by creating general insights and principles.

Once again the (evolution of) academic tradition, and the human mind, must be liberated.

Just as the case was in Galilei's time.

From the movie The Matrix I'll adopt the world as keyword—and use it to point to this so enticing yet sinister addiction that materialism thrives on—the addiction to "reality"; to "success"; which compels us to reproduce the dysfunctional habits and systems all the way until the bitter end; and to point to the urgent duty we have as generation.

Transdisciplinarity and holotopia are conceived as steps toward liberating our next generation from the world.

– [T]he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

(Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy, 1958.)

Design epistemology

You'll comprehend the category from which this foundational of holotopia's five points stems if you think of the subtle ambiguity in the word "foundation", as it's been used in this context: What Descartes was searching for, when he used that word, was the Archimedean point for acquiring "objectively true" knowledge—of "reality" as it "truly is"; which (he took this for granted) would be revealed to the mind as the sensation of absolute certainty; and which, when found (he and his colleagues also believed) would remain the lasting truth forever.

What I call foundation is what information is founded on; and culture as a whole; which—just as information—needs to be seen as a human-made thing for human purposes; so that when the foundation changes (as it did in Darwin's time)—we need to deliberately secure that the new foundation is still suitable for the all-important function it needs to perform.

I'll use ontological and pragmatic as keywords to pinpoint the nature of the fundamental error I've been telling you about, and how I propose to correct it; and say that a foundation is ontological if it rests upon the intrinsic nature of things or "reality"; that a certain way to (found) knowledge is the right one because it gives us "objective" knowledge, of the world as it truly is. My point is that we (the institution in control of this matter, the academia) must urgently develop a significant part of our activity on a pragmatic foundation—because science as it is does not tell us how to solve "the huge problems now confronting us".

And because the foundation we have is not a one on which the cultural evolution can continue.

When Nietzsche diagnosed, famously, that "Got ist tot!" (God is dead), he did not of course mean that God physically died; but that religion no longer had a foundation to stand on, that it was about to be eroded; which was needless to say true not only of religion—but of culture at large.

In the late 1990s, when this line of work was still beginning to take shape, I drafted a book manuscript titled What's Going on? and subtitled "A Cultural Renewal". The book was conceived as an information holon; whose point (pointed to by its title and an ideogram on its cover—which was a house about to collapse, with a large crack extending from its foundation to its top) was what I'm telling you here—namely that "the huge problems now confronting us" are consequences of the foundation of it all being inadequate for holding the huge edifice it now supports; and that the way to solution is not fixing but rebuilding; and that this rebuilding must begin from the foundation up. And it had, of course, also this other point—that what's really going on (i.e. what we above all need to know to consider ourselves informed) is this overall gestalt; not the fine details of 'cracks in walls' that our media informing brings us daily.

As I said—the 19th century change of foundation was not done for pragmatic reasons, but for ontological ones.

People began to believe that science (not the Bible) was the right way to truth.

You'll fully comprehend the anomaly that I am proposing to unravel (and here design epistemology is a concrete proposal pointing out that this can be done, and showing how)—when you see that the ontological argument for the present foundation has been proven wrong and disowned—by science itself!

When scientists became able to zoom in on small quanta of energy-matter—they found them behaving in ways that could not be explained in the "classical" way (as Descartes and his Enlightenment colleagues demanded); and that they even contradicted the common sense (as J. Robert Oppenheimer pointed out in Uncommon Sense)! Just as the case was at the time of Copernicus—a different way to see the world, and use the mind, was necessary to enable the physical science to continue evolving.

A careful reading of Werner Heisenberg's Physics and Philosophy will show that this book is conceived as a rigorous disproof of materialism's fundamental premises; and a call to action—to reconfigure and replace and revive culture, on a new foundation. His point was that—based on certain fundamental assumptions—science created a certain way to knowledge and experimental machinery; and when this machinery was applied to small quanta of matter-energy—the results contradicted the fundamental assumptions that served as departure point; so the whole thing has the logical structure of a proof by contradiction—which, in the present paradigm is a legitimate way of proving assumptions wrong.

Seeing that what they had uncovered had profound implications for our "edifice of knowledge" and culture at large—the giants of physics wrote popular books and essays to clarify or federate it. In Physics and Philosophy, in 1958, Werner Heisenberg pointed out that the foundation that our general culture imbibed from 19th century science was "so narrow and rigid that it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our language that had always belonged to its very substance, for instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul or of life." Since "the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided", whatever failed to be founded in this way was considered impossible or unreal. This in particular applied to those parts of our culture in which our ethical sensibilities were rooted, such as religion, which "seemed now more or less only imaginary. [...] The confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind."

The experience of modern physics constituted a rigorous disproof of this approach to knowledge, Heisenberg explained; and concluded that "one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century." Heisenberg wrote Physics and Philosophy anticipating that the most valuable gift of modern physics to humanity would be a cultural transformation; which would result from the dissolution of the narrow frame.

So what is to be done?

You already know my answer—it's what the Modernity ideogram points to; namely to fist identify the function or functions that need to be served; and then create a prototype by federating whatever points of reference or evidence may be relevant to that function; just as one would do to create the lightbulb.

What I call epistemology is the result of applying this procedure (where we first federate the way we use the mind or logos; and then use it to federate a new foundation for it all.

As an insight, design eistemology shows that a broad and solid foundation for truth and meaning, and for knowledge and culture, can be developed by this approach.

The design epistemology originated by federating the state-of-the-art epistemological findings of the giants of 20th century science and philosophy; which I'll here illustrate by quoting a single one—Einstein's "epistemological credo"; which he left us in Autobiographical Notes:

“I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. […] The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. […] All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for [scientific] inquiry in the first place.”

Design epistemology turns Einstein's "epistemological credo" into a convention.

And adds to it a purpose or function—the one we've been talking about all along.

Design epistemology as foundation is broad.

Since it expresses the phenomenological position (that it is human experience and not "objective reality" that information needs to reflect and communicate), the design epistemology gives us a foundation not only overcomes the narrow frame handicap that Heisenberg was objecting to—but also allows us to treat all cultural heritage, including cultural artifacts and even the rituals, mores and beliefs of traditions on an equal footing; by seeing it all as just records of human experience, in a variety of media; and finding similarities and patterns, and reaching insights or points. Instead of simply ignoring what fails to fit our "scientific" worldview or the narrow frame—the design epistemology empowers us and even obliges us to carefully consider and federate all forms of human experience that could be relevant to a theme or task at hand.

By convention, human experience has no a priori "right" interpretation or structure, which we can or need to "discover"; rather, experience is considered as something to which we assign meaning (as one would assign the meaning to an inkblot in Rorschach test). Multiple interpretations or insights or gestalts are possible.

Design epistemology as foundation is also solid.

Since it expresses (as a convention) the "constructivist credo"—that we are not "discovering objective reality" but constructing interpretations and explanations of human experience—the design epistemology turns the epistemological position that the Modernity ideogram expresses into a convention; it empowers us to do as Modernity ideogram calls upon us to do—and design the ways in which we see the world, and pursue knowledge. The resulting foundation is solid or "academically rigorous"—because it represents the epistemological state of the art; and because it's a convention. The added purpose can hardly be debated—because (from a pragmatic point of view) evolutionary guidance has become all-important; and because (from a theoretical point of view) a foundation of this kind is incomplete unless it has a purpose (which we can use to distinguish useful "constructions" from all those useless ones). This added function too is only a convention; a different one, and an altogether different way to knowledge can be created by the same approach to suit a different function.

Appeals to legitimate transdisciplinarity academically—if they were at all considered—have been routinely rejected on the account that they lacked "academic rigor". I'm afraid it will turn out that the contemporary academic conception of "rigor" is based on not much more than the sensation of certainty and clarity we experience when we've followed a certain prescribed procedure to the letter—as Stephen Toulmin suggested in his last book Return to Reason. It was logos Toulmin was urging us to return to; and that's been my proposal and call to action too.

– I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.

(Abraham Maslow, Psychology of Science, 1966)

Polyscopic methodology

You'll comprehend the anomaly this holotopia's insight points to, if you see method—the category the polyscopic methodology pillar in the Holotopia ideogram stems from—as the toolkit with which we construct truth and meaning, and knowledge; and consider that—as Maslow pointed out—this method is now so specialized, that it compels us to be specialized; and choose themes and set priorities (not based on whether they are practically relevant or not, but) according to what this tool enables us to do.

As an insight, the polyscopic methodology points out that a general-purpose methodology, which alleviates this problem, can be created by the proposed approach (by applying logos or knowledge federation to method); by federating the findings of giants of science and the very techniques that have been developed in the sciences—with an aim to preserve the advantages of science, and alleviate its limitations.

Design epistemology mandates such a step: When we on the one hand acknowledge that (as far as we know) there is no conclusive truth about reality; and on the other hand, that our very existence depends on information and knowledge—we are bound to be accountable for providing knowledge about the most relevant themes (notably the ones that determine our society's evolutionary course) as well as we are able; and to of course continue to improve both our knowledge and our ways to knowledge.

As long as "reality" and its "objective" descriptions constitute our reference system and provide it a foundation—we have no way of evaluating our paradigm critically. The polyscopic methodology empowers us to develop the realm of ideas as an independent reference system; where ideas are founded (not on "correspondence with reality" but) on truth by convention; and then use clearly and rigorously defined ideas to develop clear and rigorous theories—in all walks of life; as it has been common in natural sciences. Suitable theoretical constructs, notably the patterns (defined as "abstract relationships", which have in this generalized science a similar role as mathematical functions do in traditional sciences) enable us to formulate general results and theories, including the gestalts; suitable justification methods (I prefer the word "justification" to the commonly used word "proof", for obvious reasons) can then be developed as social processes; as an up-to-date alternative to "peer reviews" (which have, needless to say, originated in a world where "scientific truth" was believed to be "objective" and ever-lasting).

The details of polyscopic methodology or polyscopy are beyond this brief sketch; and I'll only give you this hint: Once it's been formulated and theorized in the realm of ideas, a pattern can be used to justify a result; since (by convention) the substance of it all is human experience, and since (by convention) experience does not have an a priori "real" structure that can or needs to be "discovered"—a result can be configured as the claim that the dots can be connected in a certain specific way (as shown by the pattern) and make sense; and its justification can be conceived in a manner that resembles the "repeatable experiment"—which is "repeatable" to the extent that different people can see the pattern in the data. This social social process can then further be refined to embody also other desirable characteristics, such as "falsifiability"; I'll come back to this in a moment, and also show an example.

– The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future.

(Aurelio Peccei, One Hundred Pages for the Future, 1981)

Convenience paradox

How do you raise a child in a culture whose values are in significant dimensions opposite from yours?

Noah and I have been having a series of dialogs whose shared theme or red thread is epistemology (when he was a baby, I joked that "epistemology" would be the first word he'd learn). It's late December in Oslo now, Christmas is in the air; so the other day I played to Noah versions of the "Oh Happy Day" gospel by several gospel choirs on YouTube; where "Oh happy day, when Jesus washed (...) my sins away" is emphatically and enthusiastically repeated. I asked Noah to imagine what a materialist might think about this message: "Jesus died centuries ago; these poor souls don't understand that he most certainly cannot do anything for them..." And yet when you look at the faces of the gospel singers, and listen to the way they sing—you cannot but conclude that the joyful experience they are singing about does exist; that there's an exquisite sort of "high" that people can reach through certain practice; and that music or chanting in quire can help both in reaching and in communicating this experience. And if you are in doubt—you may move on next door, to the Sufis; or to the Suan Mokkh forest monastery in Southern Thailand; where the language, the symbolism and the ritual may be in some ways different and in other ways similar—and yet have the same joyful-exuberant experience as result—with interesting variations.

A vast creative frontier opens up—for academic and personal.

As soon as we step beyond the belief system of materialism—and use logos to (create epistemology and methodology and ) explore in a systematic way such basic themes as "happiness" and "values"; and importantly—how they are related to each other. Which is—now you'll now easily comprehend that—what "Religion beyond Belief", the Liberation book's subtitle is hinting at.

What I've just described was quite accurately my own way into and through this creative frontier; convenience paradox was the very first prototype result of this line of work. I presented in 1995, at Einstein Meets Magritte (in addition to a parallel methodology "prospectus" paper); and I've been working on it off and on ever since.

Convenience paradox is one of holotopia's five insights.

You'll appreciate the relevance of the convenience paradox insight if you consider it in the context of our contemporary condition: The evolutionary course of materialism—marked by growth of material production and consumption—must be urgently changed (certainly in the "developed" parts of the world, and arguably in other parts too); but to what? It seems that everyone who has looked into this question concluded that the pursuit of humanistic or cultural goals and values will have to be the answer; you can hear this straight from the horse's mouth.

You'll begin to see the anomaly this point points to if you consider the obvious—desensitization; the more our senses are stimulated—the less sensitive they'll become; but where shall we draw the line? Could fasting (and making our senses more sensitive) could be a better way to gastronomic pleasure than eating until our stomach hurt? Already at the turn of the nineteenth century Nietzsche saw his contemporary "modern" human as so overwhelmed by "the abundance of disparate impressions", that he "instinctively resists taking in anything, taking anything deeply, to ‘digest’ anything"; so that "a kind of adaptation to this flood of impressions takes place: men unlearn spontaneous action, they merely react to stimuli from outside." What would Nietzsche say if he saw us today?

Convenience in the role of 'headlights' (or way to determine the know-what) leaves in the dark one whole dimension of physical reality—time; and also an important side or one could even say the important 'half' of the three dimensions of space—its inner or embodied part; I emphasize its importance because while "happiness" (or whatever else we may choose to pursue on similar grounds) appears to be "caused" by events in the outer world—it is inside us that our emotions materialize; and it is there that the difference that makes a difference can and needs to be made.

Did you notice, by the way—when you watched the video I've just shared (and if you haven't watched it, do it now; because it's the state of the world diagnosed by the world's foremost expert—who studied and federated this theme for more than four decades—condensed in a six-minute trailer)—how Dennis Meadows, while pointing in this new evolutionary direction, struggled to find the words that would do it justice; and came up with little more than "knowledge" and "music"?

This is where the Liberation book really takes off!

Its entire first half (its first five chapters) is dedicated to mapping not only specific opportunities, but five whole realms where we may dramatically improve our condition through inner development; whereby a roadmap to inner wholeness is drafted, as the book calls it. The Liberation book opens with an amusing little ruse—where a note about freedom and democracy is followed by the observation that we are free to "pursue happiness as we please"; and I imagined the reader would say "Sure—what could possibly be wrong about that?" But what do we really know about "happiness"? And whether "happiness" is at all what we out to be pursuing? Perhaps "love" could be a better choice? So let me for a moment zoom in on "love" as theme; which hardly needs an explanation—considering how much, both in our personal lives and in our culture, revolves around it: "My baby's gone, and I got the blues, It sure is awful to be lonsesome like me, Worried, weary up in a tree." The Liberation book invites us to look at this theme from a freshly different viewpoint: What sort of "love"—or what quality of love—are any of us really capable of experiencing? Can you imagine a world where we are culturally empowered to cultivate love; including our ability to experience love and importantly—to give love? In the third chapter of the Liberation book, which has "Liberation of Emotions" as title, phenomenological evidence for illuminating this realm of questions is drawn from the tradition of Sufism; in order to demonstrate that love has a spectrum of possibilities that reaches far beyond the outreach of our common experience and even awareness; and that certain kinds of practice, which combine poetry and music with meditation and ethical behavior, can make us, in the long run capable of experiencing the kinds of love whose very existence we as culture ignore; which can make our experience of poetry and music too incomparably more nuanced and rewarding.

Convenience paradox is the point of a very large information holon; which asserts (and invites us to turn it into shared and acted-upon fact, by giving it a similar visibility and credibility as what the "Newton's Laws" now enjoy) that convenience is a useless and deceptive "value", behind which a myriad opportunities to improve our lives and condition—through cultural pursuits—await to be uncovered. The rectangle of this information holon is populated by a broad range of—curated—ways to improve our condition through cultural pursuits or by human development (which Peccei qualified as the most important goal).

Originally, the convenience paradox result was conceived as a proof-of-concept application of polyscopic methodology; I showed preliminary versions of both in 1995, at the Einstein Meets Magritte conference that the transdisciplinary center Leo Apostel and Brussels Free University organized (this conference marked the turning point in my career); the corresponding articles were published in 1999 in the "Yellow Book" of the proceedings titled World Views and the Problem of Synthesis. My point was to show how the methodological approach to knowledge I've been telling you about here (which empowers us to consider all forms and all records of human experience as data; and to synthesize and justify general and overarching insights as patterns; and to communicate them and make them palpable through ideograms) can allow us to collect and combine culturally relevant experiences and insights across worldviews and cultural traditions; and to give them visibility and citizenship rights; and empower them to impact our culture. I've been working this so fascinating creative frontier ever since.

The Liberation book too is a fruit of this line of work. The entire book can be seen as a prototype of a system—for empowering or federating culture-transformative experiences and insights or memes. The book is conceived as a federation of a single such meme—the legacy and vision of Buddhadasa, Thailand's 20th century holy man and Buddhism reformer; who—anticipating that something essential may have been misunderstood—withdrew to an abandoned forest monastery near his native village Chaya, to practice and experiment as Buddha did in his day. Having seen what he found out as potential antidote to (the global onslaught of) materialism, and also as the (still widely ignored) shared essence of the great religions of the world—Buddhadasa undertook to do whatever he could to make his insight available to both Thai people and foreigners.

It should go without saying that the Buddhadasa meme (as I call it in the book) makes no sense in the context of materialism—which it undertakes to transform. The Liberation book alleviates this problem by drafting a different context—so that Buddhadasa's transformative insights can be seen as an essential elements in a new and emerging order of things (envisioned as holotopia); or metaphorically—as a vital organ of the elephant.

– Many years ago, I dreamed that digital technology could greatly augment our collective human capabilities for dealing with complex, urgent problems.

(Doug Engelbart, "Dreaming of the Future*, BYTE Magazine, 1995)

Knowledge federation

David Graeber and David Wengrow wrote in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity: "There is no doubt that something has gone terribly wrong with the world. A very small percentage of its population do control the fate of almost everyone else, and they are doing it in an increasingly disastrous fashion." Why am I quoting (from a book that offers us a wealth of insights, emerging from scientific studies in ethnography, about latent opportunities for configuring human relations and society that are beyond materialism) something that "everyone knows"? Because I'm about to tell you why I passionately disagree with it! And in the same breath introduce to you communication as the category from which knowledge federation stems as point or insight; and also Norbert Wiener as yet another ignored giant. And a giant he manifestly was—having earned academic degrees in mathematics, zoology and philosophy, and then a doctorate in mathematical logic from Harvard while he was still a teenager! Wiener then went on to do seminal work in a variety of fields, one of which was cybernetics (but not alone; Margaret Mead was a member of the small transdisciplinary circle from which cybernetics emerged). Wiener's ignored point was already in the title of his seminal Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine: Control and communication are inextricably connected; control depends on right or correct communication. You'll see this if you just think of the bus with candle headlights: We who are in the bus do see someone sitting behind the steering wheel, and think he's in control; and there is, of course a fierce battle inside the buss for those "driver" positions (which are, indeed, available to only a few people, as Graeber & Wengrow observed). But in the larger picture—are they really in control? Will anyone benefit from steering the society in a "disastrous fashion"?

The word "cybernetics" is derived from Greek "kubernan (to steer); it is related to the English noun "government" and the verb "to govern". As an academic field, cybernetics is dedicated to the study of governability—or more precisely, what structure do systems need to have to be viably governable or "sustainable" (Wiener framed this question by using "homeostasis" as technical keyword—to point to an organism's or system's activities to maintain a stable or viable course). Wiener's all-important and still flagrantly ignored point was that "free competition" won't do (he called the belief that we can rely on it a "simpleminded theory" which contradicts the evidence). The point of it all is that to make our systems viable or "sustainable"—we must learn about the relationship between communication and control by studying living systems ("the animal") and technical systems ("the machine")—and apply the resulting insights there where they'll make the largest difference—in the design and control of society and its systems.

Isn't this what we've been talking about all along?

In social systems—composed of relatively autonomous individuals—communication is the system, Wiener pointed out in Cybernetics; and he talked about ants and bees to demonstrate that. You'll comprehend the anomaly that knowledge federation as holotopia's point points to if you consider that the "digital technology"—the interactive, network-interconnected digital media you and I use to read email and browse the Web—has been envisioned (by Doug Engelbart—already in 1951!) and developed (by his SRI-based team, and publicly demonstrated in 1968) to serve as "a collective nervous system" of a radically novel kind; and enable a quantum leap in the evolution of our "collective social organisms"—which would dramatically augment their—and our—"capabilities for dealing with complex, urgent problems". You'll easily see what all this means if you imagine us all traveling in that so horrid bus—rushing off-chart at an accelerating speed and dodging trees: We must be able to act fast; and if also we want to give the whole thing a viable direction—we must be able to synthesize a whole new view of the world (which shows us forests, not trees); and use it for steering. The key to grasping the gist of Engelbart's vision—which I'll refer to as collective mind—is his acronym CoDIAK; which stands for "concurrent development, integration and application of knowledge. Take a moment to reflect on his word "concurrent": Every other technology I can think of—including handwritten letters carried by caravans and books printed by Gutenberg—require that a physical object with the message be physically carried from its author to its recipient; only this Engelbart's technology provided the genuine functionality of the nervous system—which enables us, and indeed compels us to "develop, integrate and apply" knowledge concurrently, as cells in a single human mind do; but of course—to take advantage of this technology, to realize this possibility, our communication needs to be structured and organized in entirely new ways; which is, of course, what knowledge federation is all about. Imagine if your cells were using your nervous system to merely broadcast data—and you'll easily see what I'm talking about.

You'll see the related anomaly if you notice that this technology is still largely used to send back and forth messages and publish or broadcast documents—i.e. to implement and speed up the sort of processes that the old technologies of communication made possible (here Noah, my thirteen-year-old, would instantly object; so I must qualify that it's academic or "serious" communication I am talking about). Or to use knowledge federation's lead metaphor:

'Electrical technology' is still used to produce 'fancy candles'.

Substantial parts of the knowledge federation prototype have been developed by a community of knowledge media researchers and developers committed to continuing and completing the work on Engelbart's vision—by creating completely different systems that this technology enables; and taking part in the quantum leap in the evolution of humanity's core systems—which this technology enables, and our situation necessitates. I'll here illustrate this line of work by a single example—our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 prototype; where we showed how academic communication can be updated, to benefit the society far more than it presently does.

To begin, I'll invite you to see the academic system as a gigantic socio-technical 'machine' that takes as input gifted young people and society's resources; and produces creative people and ideas as output; and explore the question that follows—How suitable is this system for its all-important role? In a moment I'll show you the prototype where the result of an academic researcher has been federated; but before I do that let us zoom in even further, and examine how a researcher's result is handled in our present system—which first subjects it to "peer reviews" (which made sense in those good old days when it was academically legitimate to believe that conforming to a traditional disciplinary procedure and that alone would qualify a result as worthy of being included in "the edifice of knowledge"; that once it passed that test—if would remain part of this edifice forever; which today has as unhappy consequence that it keeps academic creativity all too narrowly confined—to so-called "safe" which means not-so-novel areas) and then—if it receives a passing grade—commits it to academic bookshelves; where nobody will ever find it—except those few specialists to whom it's addressed; who are anyhow the only ones who can comprehend what the result is all about.

In our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 prototype we federated the result of a researcher—University of Belgrade's Dejan Raković—in three phases; where:

- The first phase was to make the result comprehensible to lay audiences; which we (concretely knowledge federation's communication design team) did by turning this technical research article into a multimedia object; where its main points were extracted and connected and made comprehensible by explanatory diagrams or ideograms; and further clarified by (placing on them links to) recorded interviews with the author

- In the second phase we made the result known and at the same time discussed in space, by leading international experts on Tesla—by staging a televised and streamed high-profile dialog at Sava Center Belgrade

- The third phase constituted a technology-enabled global social process (we used DebateGraph) by which the result was processed further, .

This third stage is in particular illustrative of the vast difference the new media technology can make—once we use it to re-create our "social life of information"; here the points that were extracted and explained in the first phase were made available online as DebateGraph nodes; so that other experts or DebateGraph users—anywhere in the world—can add to them new nodes, corresponding to the sort of action they deem appropriate: They may add supporting evidence; or challenge the result by counterevidence and so on. Here (not the reviewers' verdict on an academic article, but) this connecting the dots—this new creative process of this new collective mind—is allowed to continue forever. Two MS theses were developed to complement and complete this prototype: One of them made it possible to create 'dialects' on DebateGraph (which determine what actions or moves can be applied to a certain kind of node, such as an idea, or an negative or positive evaluation of an idea); and effect program "the social life" of academic information. The other MS thesis prototyped two objects called domain map and value matrix; which enabled both authors and their contributions to be evaluated by multiple criteria.

Also the theme of Raković's result—the nature of the creative process that distinguishes "creative genius"—must be taken into consideration to fully comprehend this prototype: Raković first demonstrated phenomenologically (by referring to Nikola Tesla's own descriptions of his creative process) that there are two distinct kinds of creativity; and that the "outside the box" creativity necessitates an entirely different creative process, and ecology of mind, distinct from its common alternative; and he then theorized this creative process within the paradigm of quantum physics. Imagine if it turns out that the way we (teach the young people how to) think and use the mind, at schools and universities—which happens to be the kind of creative work that the machines are now doing quite well—inhibits this entirely different process that we ought to be using, and teaching! I open the "Liberation of Mind" chapter of the Liberation book with anecdotes involving Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen; to hint that the evidence for it is overwhelming, that it's staring us in the eye! And so the question—the key question—is by what social process are we handling this and other similar pivotal questions?

With this in mind, compare the federation process I've just outlined—which (1) models the phenomenology of Tesla's creative process; (2) submits this phenomenology outline to expert researchers and biographers of Tesla and (3) proposes an explanatory model of this process as a prototype—available online, with provisions to be indefinitely improved—to a peer review; which will say "yes" or "no" depending on whether the model is stated and "proven" by a certain hereditary procedure.

Isn't all this just a way to keep the humanity's creative powers in the proverbial 'box'?

"So you are creating a collective Tesla", Serbian TV anchor commented while conversing with our representative in the studio; and rendered the gist of our initiative better than I have been able to.

– The task is nothing less than to build a new society and new institutions for it. With technology having become the most powerful change agent in our society, decisive battles will be won or lost by the measure of how seriously we take the challenge of restructuring the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.

(Erich Jantsch, Integrative Planning for the "Joint Systems" of Society and Technology—the Emerging Role of the University, MIT Report,1969)

Systemic innovation

You'll see the relevance of innovation—the category from which this insight stems—if you consider that it's both (whereby we use and direct our technology-augmented power to create and induce change, and hence) what drives the metaphorical bus forward and what needs to be redirected so that its headlights can be replaced.

You'll see the "different" way of looking at innovation, by which it can be comprehended in a new way and corrected, if you imagine the systems in which we live and work as gigantic machines, comprising people and technology; and acknowledge that they determine how we live and work; and importantly, what the effects of our work will be—whether they'll be problems, or solutions. Béla H. Bánáthy wrote in Designing Social Systems in a Changing World:

“I have become increasingly convinced that [people] cannot give direction to their lives, they cannot forge their destiny, they cannot take charge of their future—unless they also develop the competence to take part directly and authentically in the design of the systems in which they live and work, and reclaim their right to do so. This is what true empowerment is about.”

How suitable are our systems for the functions they need to perform "in a changing world"?

If the system whose function is to enable us to direct our efforts correctly is a 'candle'—what about all others? How suitable are our financial system, our governance, our international corporation and our education for what they need to be able to achieve?

In 2013 I was invited to give an online talk to a workshop of social scientists who convened at IUC Dubrovnik; who were interested in journalism, IT innovation and e-democracy. The title I gave my talk was "Toward a Scientific Comprehension and Handling of Problems", in order to draw attention to my main point—namely that there is an altogether different or "scientific" way to comprehend and handle the society's ills that journalism reports, and innovation and democracy aim to resolve. To explain and justify this point, I drafted a parallel between the society and the human organism—and invited my audience to see communication as the society's nervous system, finance as its vascular system, the corporation as its muscular system, education as reproductive system and so on; and I demonstrated, one by one, that what we see as society's problems are indeed (or need to be seen as) symptoms of systemic malfunction. Scientific medicine distinguishes itself by comprehending and handling symptoms in terms of the anatomy and pathophysiology that underlie them, my point was; why not comprehend and handle our society's issues in a similar, scientific way?

I ended my talk on a positive note; by showing a photo of an electoral victory, to which I added in Photoshop "The systems, stupid!" as featured winning electoral slogan; which was, of course, a paraphrase of Bill Clinton's winning 1992 slogan "The Economy, stupid!" In a society where the survival of businesses depends on their ability to sell people things—of course one needs to keep the economy growing if one wants the business to be profitable and the people employed. But economic growth is not "the solution to our problem".

Systemic innovation empowers us to change the system of our economy.

Instead of only adapting to it, until the bitter end.

In the Liberation book (where, as I said, I explain abstract ideas by telling people stories), I let Erich Jantsch iconize systemic innovation. I introduce Jantsch's legacy and vision by qualifying them as the environmental movement's forgotten history; and its ignored theory; which we'll have to comprehend to be able to act, instead of only reacting.

In the story we meet Jantsch at the point where he's just given his keynote to The Club of Rome's inaugural meeting in 1968 in Rome. Jantsch readily saw what needed to be done to pave the way to solutions; and right away convened a workshop of a hand-picked team of experts—to craft systemic innovation theory and methodology; and then—seeing that the university is the only institution capable of developing and spearheading this new way to think and act—spent a semester at MIT drafting a plan for the transdisciplinary university, from which I quoted the above excerpt; and lobbying with the MIT academic colleagues and administration to implement this necessary and so timely change.

Then there was this wonderful turn of events—which spices up both the story of Jantsch and systemic innovation, and the story of Engelbart and knowledge federation I shared a moment ago: During the 1970s Jantsch and Engelbart were practically neighbors—separated only by the San Francisco Bay! But they never met or collaborated—even though each of them needed the other to fulfill his own larger-than-life mission: Engelbart was struggling to explain to Silicon Valley businesses and innovators that innovation needed to be directed in an entirely different way; that the technology he gave them was intended to serve as enabler for an quantum leap in evolution of humanity's systems. And just across the bay there was this other ignored giant, with the complementary message. Let me be blunt: Would you choose to leave your children loads and loads of dough—and a world about to collapsed on their heads? I mean—if you knew what was going on; and that you could make a difference.

But Jantsch didn't stop there; during the 1970s, until his premature death in 1980, Jantsch was earnestly and with all his power developing a different view of the elephant (and supporting himself by working as a music critic); he gave it different names in different publications, and I'll call it evolutionary vision; as Jantsch did in the last expert workshop he organized, and his corresponding last book he edited.

The turning point in Jantsch's creative process was the talk that Ilya Prigogine gave U.C. Berkeley (where Jantsch was an adjunct assistant professor; I adopted this keyword from Doug Engelbart to use it as he did—to point to the highest academic position available to system reformers) about his work (for which he received the Nobel Prize five years later); which showed Jantsch that even physical systems follow a certain peculiar evolutionary dynamic. You'll comprehend the gist of it if you think for a moment about the key point of cybernetics (in the context of the error I am inviting you to correct, and the challenge of making our society's evolutionary course governable or sustainable): Wiener's idea of control (he used "homeostasis" as keyword to pinpoint it) was the maintenance of a certain equilibrium state or condition; and using "communication and control" to avoid and eliminate the deviations. What Jantsch saw (and also Prigogine) was an entirely different evolutionary dynamic—where the system operates in a state that is far from equilibrium; in a manner that is in a fundamental sense creative.

In Design for Evolution, his 1975 seminal work, Jantsch introduced the evolutionary vision by inviting us to see ourselves as passengers (not in a bus but) in a boat on a river. The traditional sciences would have us look at the boat from above, Jantsch explained—and aim to describe it "objectively"; the traditional systems science would position us on the boat—and instruct us how to steer it safely. The evolutionary vision would have us to see ourselves as—the river! The point of it all being that the way we present ourselves to evolution is what determines its course!

Why am I telling you at length about these so technical themes?

Because we've just placed the Liberation book's overall main point into this website's all-important context (our quest or guiding light or know-what): According to evolutionary vision, the "liberated" or "enlightened" condition this book portrays is "the solution to our problem".

– Modernity did not make people more cruel; it only invented a way in which cruel things could be done by non-cruel people. Under the sign of modernity, evil does not need any more evil people. Rational people, men and women well riveted into the impersonal, adiaphorized network of modern organization, will do perfectly.

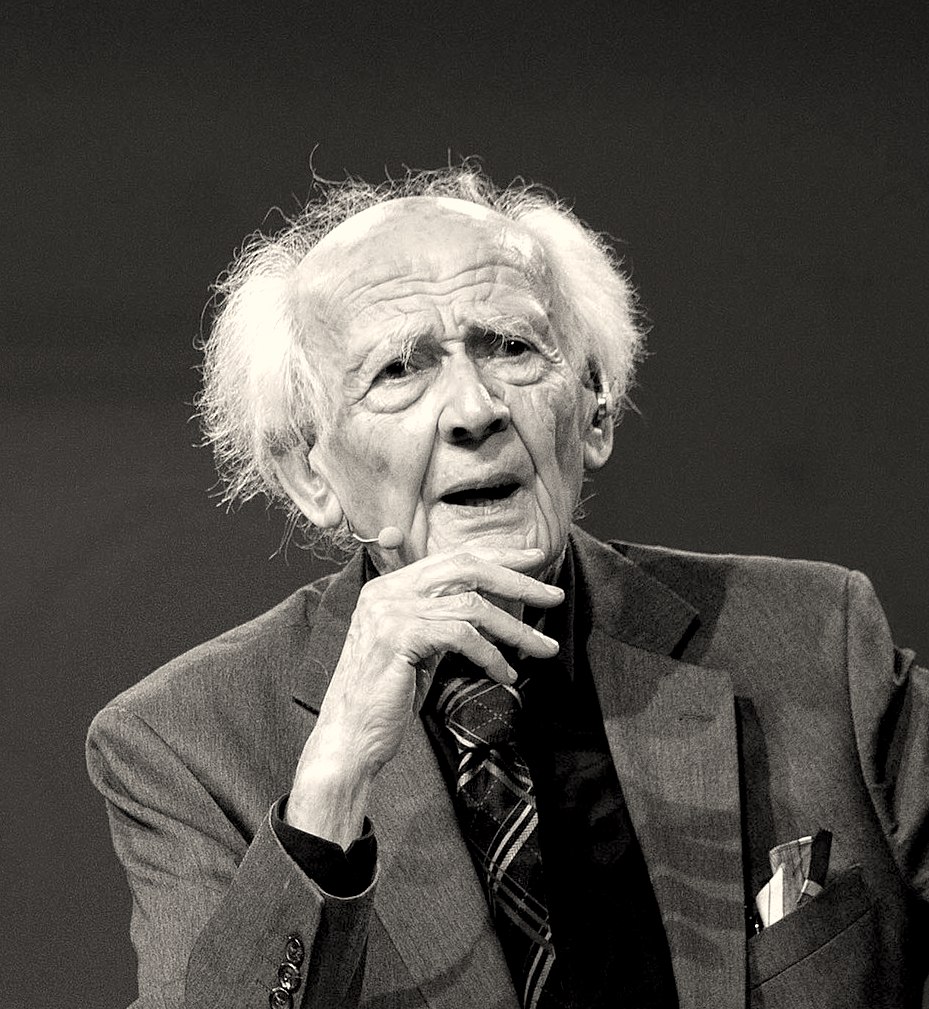

(Zygmunt Bauman Life in Fragments: Essays in Postmodern Morality, 1995)

Power structure

Before we can solve "the huge problems now confronting us", we need to diagnose them correctly.

Power structure is a social-and-cultural disease.

It is also an update or redesign of the traditional idea of the enemy. The power structure is not a physical entity but a pattern; it is not bacteria-like but cancer-like. It has similar effects on our minds and liberties as a dictator; but it remains invisible—as long as we look at freedom and justice in any of our inherited or traditional ways. The power structure is not a conspiracy theory but its exact opposite: The people who co-created it have no evil intentions; and indeed not a faintest idea that they might be part of the problem. Before I say more about it, let me bring this down to earth by sharing how I got to be aware of power structure.

When around 1995 I caught a glimpse of the vast and wondrous creative frontier I've been telling you about, and reconfigured my life and my work to be able to focus on it fully—I anticipated a completely different dynamic than what I actually encountered: I expected a spirited conversation; and perhaps some doubt and disbelief to begin with. What I got instead was—silence; accompanied with a vague sense of discomfort. Evidently, I was doing something wrong; but even that was only communicated in body language. Could it be that the academic culture is not steered by academic logos, as I took it for granted; but by something quite different, which I could not even name? The experience was disheartening; it's as if you put all your chips on being a painter; and work with all your power to manifest all those wonderful images you were carrying in intuition—only to realize that your fellow painters and gallerists are color blind! But when I explored this phenomenon a bit, I realized that what I was experiencing was not just some weird anomaly, but the problem—that's preventing us from solving "the grave problems now confronting us"; and so naturally, I undertook to research it thoroughly. It was at that point that I undertook to explore the related results humanities, about which I knew next to nothing.

Here in front of me on the table I have Zygmunt Bauman's book Modernity and the Holocaust; which—as I am now re-reading it—reflects back to me a closely similar message—namely that there is something essential we still ignore about ourselves and our society, and importantly—about the relationship between us and society (Bauman's "we" included his fellow sociologists). When we theorize the Holocaust while ignoring that all-important something—we see it as "an interruption in the normal flow of history, a cancerous growth on the body of civilized society, a momentary madness among sanity"; whereas when we look carefully at how it really developed (as documented by the historians)—we are bound to see it as just an extreme case of a pathology that permeates our society; which by being so extreme—invites us to comprehend that all-permeating pathology. Hannah Arendt left us a similar message when she talked about "banality of evil"; but her diagnoses too were ignored, and considered "controversial".

These warning we must urgently attend to.

Because the banal evil is acquiring grotesque proportions! I am considering to use geocide as keyword to rub it in; but perhaps you already got my point?

At InfoDesign 2000 conference in Coventry, GB, I presented the power structure theory alongside with polyscopic methodology; and introduced the former as a proof-of-concept application of the latter.

We must look through the holoscope to diagnose the society's deadly disease!

In Coventry I was invited to elaborate both ideas in Information Design Journal; which resulted in two publications: "Designing Information Design" introduced the methodological or design approach to information and gave (an early version of) the same call to action I am proposing here; "Information for Conscious Choice" introduced the power structure theory and a pragmatic argument for that call to action: "Free competition" and the related notion of "free choice" is what's breeding the power structure and driving us to extinction; our choices must be illuminated by suitable or designed information.

The Power Structure ideogram consists of three white entities joined together by three black arrows; and suggests that the power structure is not a distinct thing but a structure—comprising known entities and their subtle relationships. The entities are power (represented in the ideogram by a dollar sign), information (represented by a book), and our personal and socio-cultural wholeness (represented by a stethoscope). The point here is that "the enemy", that what really has the power over us the people is not any of those three things alone—but their combination; or more to the point—their synergy.

The reason why those relationships remained invisible and ignored is that they are not mechanical but evolutionary; it is (not deliberate scheming but) evolution that adjusts those three (obviously co-dependent) entities to each other; and turns them into something that for all practical purposes acts as an organism.

I used results and insights from multiple fields of science to elaborate the power structure as a pattern: The basic insights from stochastic optimization, artificial intelligence and artificial life—to show that co-dependent entities can co-evolve to form a coherent structure, which can behave as if it were intelligent and alive; Antonio Damasio's revolutionizing insights in cognitive neuroscience, explained in his book appropriately titled Descartes' Error—to point to the pre-conscious and embodied and hence 'programmable' nature of (what's believed to be) "free choice"; and Pierre Bourdieu's explorations of of "symbolic power" and his "theory of practice" to explain the power structure dynamic; and how it's related to economic and political power.

The power structures exist at distinct levels of generality or details; smaller power structures compose together larger ones; so that we are justified in seeing it all as just the (one single) power structure.

I used metaphors to make this invisible enemy comprehensible and palpable; one of which was cancer: The power structure is a cancer-like deformation of society's 'tissues and organs'; which—unless it's recognized and countered by society's 'immune system'—can proliferate and be fatal.

Bourdieu left us a pair of useful metaphors and keywords, "field" and "game"; which he used interchangeably to describe the dynamics of power structure. imagine us all as tiny magnets immersed in a large magnetic field; which subtly orients our seemingly free or random behavior; which—as we align ourselves with it—becomes stronger. The power structure, or "field", then gamifies the society; and reduces for each of us the disturbing complexity of our world to just learning a social role and performing in it; which gives us "ontological security" and eliminates the need for ethics and for knowledge, as Giddens pointed out.

Power structure is not a pejorative label but a way of looking.

As long as we live in a society—we are affected by power structure and we must see to it that this co-dependence is minimal; because both our freedom and our society's future depend on our liberation.

Power structure is not one of holotopia's five insights; it is, however, a theme that permeates all of them, and the Liberation book; which gives us a way to revisit and revise other themes including