IMAGES

Contents

Federation through Ideograms

(Neil Postman in a televised interview to Open Mind, 1990)

"[...] of people not having any basis for knowing what is relevant, what is irrelevant, what is useful, what is not useful, where they live in a culture that is simply committed, through all of its media, to generate tons of information every hour, without categorizing it in any way for you", Postman continued.

Knowledge federation is a social process whose function is to connect the dots.

And complement publishing and broadcasting by adding meaning or insights to overloads of data; and by ensuring that those insights are acted on.

Among various sorts of insights, of especial importance are gestalts; of which "Our house is on fire" is the canonical example: You may know all the room temperatures and other data; but it is only when you know that your house is on fire that you are empowered to act as your situation demands. A gestalt can ignite an emotional response; it can inject adrenaline into your bloodstream.

We use the word gestalt to pinpoint what the word informed means.

Our traditions have instructed us how to handle situations and contingencies by providing us a repertoire of gestalt and action pairs. But what about those situations that have not happened before?

Knowledge federation uses ideograms to create and communicate gestalts and other insights. An ideogram can condense one thousand words into an image; and make the point of it all recognizable at a glance; and communicate know-what in ways that incite action.

The existing knowledge federation ideograms are only a placeholder—for a variety of techniques that will be developed through artful and judicious use of media technology.

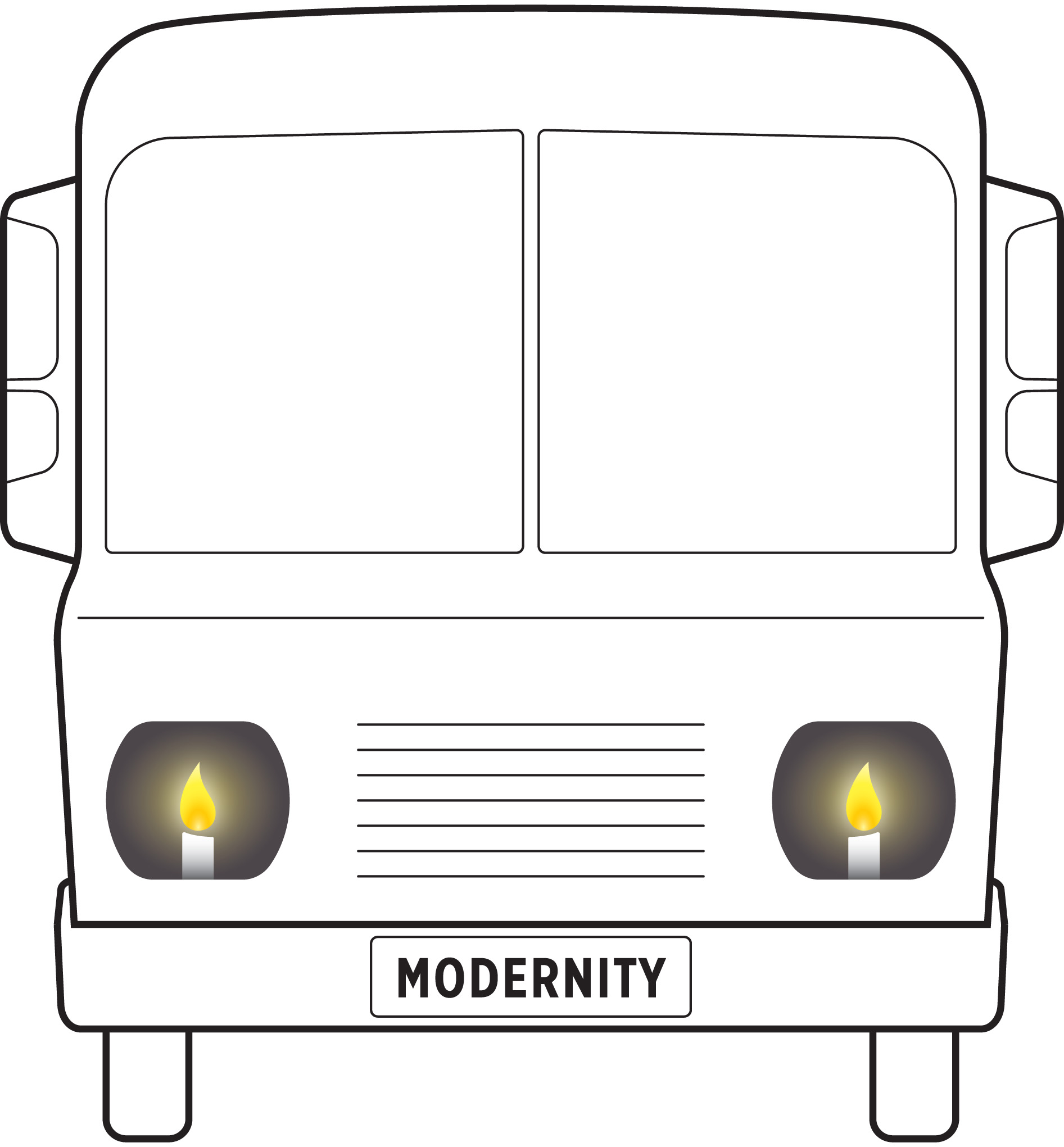

Modernity ideogram explains the error that is the theme of this proposal.

Modernity ideogram

By depicting our society as a bus and our information as its candle headlights, Modernity ideogram renders the gestalt of our contemporary condition in a nutshell.

Imagine us as passengers in this bus—as it rushes at accelerating speed (by virtue of its technologies becoming better) toward a certain disaster (because we lack the vision that would empower us to direct it beneficially and safely). When I think of this bus I imagining it already off track, struggling to dodge trees; this struggle being the only thing that gives it direction.

Modernity ideogram points to fundamental roots of this uncanny error.</p>

<h3>Nobody in his right mind would design this strange vehicle; the only way in which this could happen is if the people who created it never even considered the options; if they reified whatever source of illumination they had inherited from the past as headlights, without giving this matter a thought.</p>

In One Hundred Pages for the Future, in 1981, based on a decade of The Club of Rome's research into the future prospects of mankind, Aurelio Peccei—this global think tank's president and co-founder—concluded: “It is absolutely necessary to find a way to change course.” How can we possibly change course while we have 'candles' as 'headlights'?

<h3>Information must intervene between us and the world.

And not just any information—but information that's been conscientiously designed for that pivotal function (I qualify something as pivotal if it decisively influences our society's evolutionary course; and as correct if it corrects it).

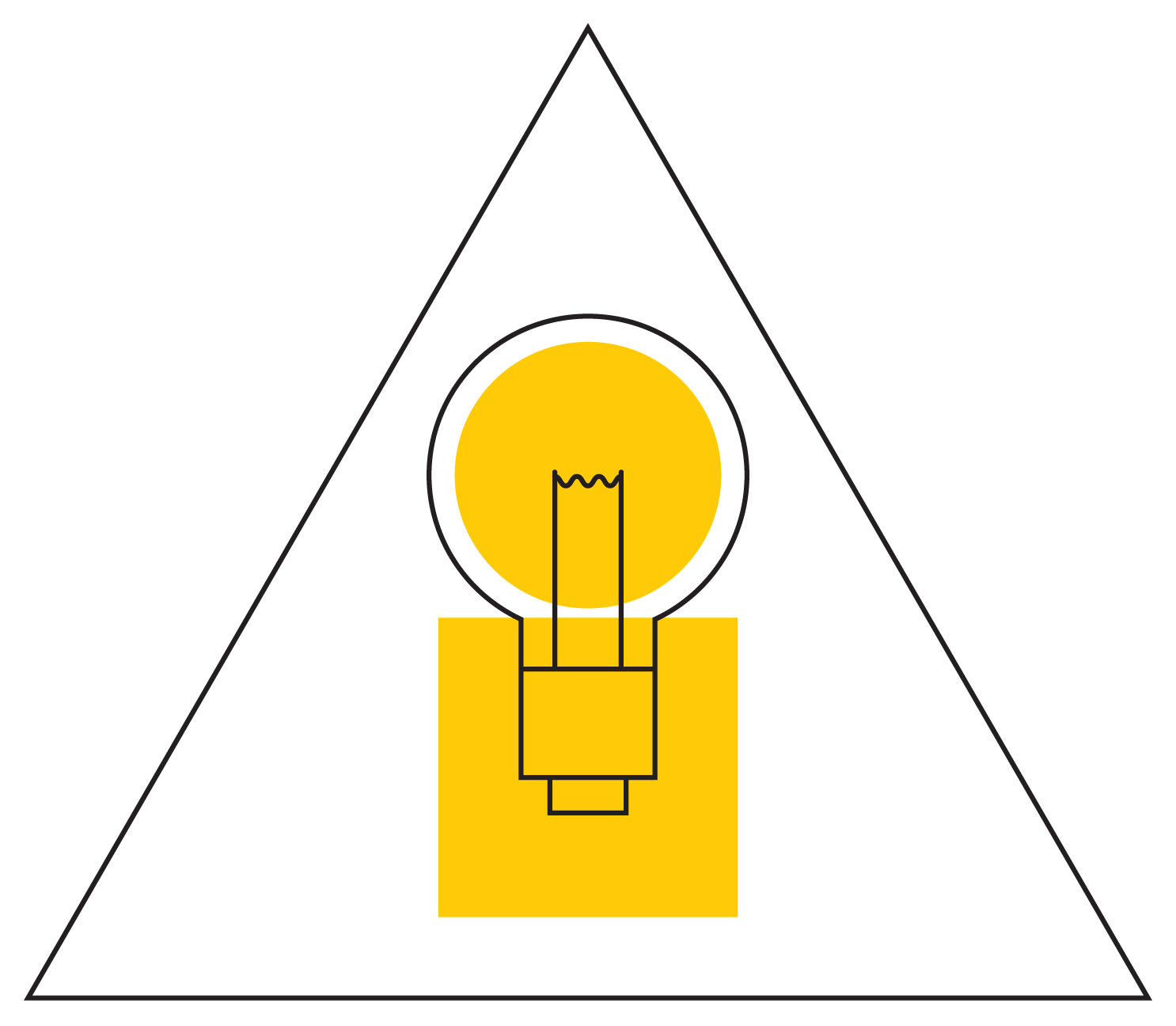

Information ideogram depicts the (socio-technical) lightbulb.

Information ideogram

What should information be like—to empower us to see the world correctly?

My aim is not to answer this question—but to set in motion a social process; by which the answer will be created, and continually re-created.

That's how knowledge federation needs to be understood.

As the name for an evolving social process; which is both the principle of operation of the socio-technical 'lightbulb'—and the (institutionalized) social process by which it can and needs to be created.

Why exactly this name? I am copying and pasting straight from the Liberation book: To justifiably say I know, to step over that all-important threshold that separates believing from knowing, I must consider the evidence. It may seem to me that the Earth is flat and I might even believe that; but people have traveled around the Earth; and others saw it from outer space. When I take account of evidence—I cannot but change my mind.

Notice also: I cannot claim that something is known unless it’s manifested in everyday awareness and action. Every rational system of thought must ultimately rest upon a fundamental principle or axiom that cannot be argued within that system. Knowledge federation stems from this single and simple knowledge federation axiom:

Knowledge must be federated.

To federate knowledge means to account for academic results, people’s experiences, cultural artifacts and whatever else might be relevant to the theme or task at hand. Political federation unites smaller geopolitical units to give them visibility and power.

Knowledge federation does that to information.

We are now facing a most interesting creative challenge: What exactly do we need to do—to create the socio-technical 'lightbulb'? And to replace that so spectacularly dysfunctional 'candle'? Surely this process must involve a prototype; because regardless of how hard we try—we'll never create the lightbulb by improving the candle. The rest is what I've told you—we need to federate the prototype 'lightbulb'; by accounting for what's been found out in the sciences, and for whatever else that may be relevant; which I'll here illustrate by a single example—the Object Oriented Methodology; which constituted a landmark in the history of computer programming. Ole-Johan Dahl (who later received the Turing Award—the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in computing—for this work) wrote (with C.A.R. Hoare) in Structured Programming in 1972, in a chapter called “Hierarchical Program Structures”:

“As the result of the large capacity of computing instruments, we have to deal with computing processes of such complexity that they can hardly be understood in terms of basic general purpose concepts. The limit is set by the nature of our intellect: precise thinking is possible only in terms of a small number of elements at a time. The only efficient way to deal with complicated systems is in a hierarchical fashion. The dynamic system is constructed and understood in terms of high level concepts, which are in turn constructed and understood in terms of lower level concepts, and so forth.”

If computer programming was not to result in chaos, but in code that's easily comprehensible, reusable and modifiable—the programs would need to be structured in a way that conforms to the limits of our intellect, Dahl and his colleagues found out; and created the Object Oriented Methodology which enabled the programmers to achieve exactly that—by structuring the programs in terms of "objects".

I adapted this idea and drafted the information holon; which is what the Information ideogram depicts. Arthur Koestler coined the keyword "holon" to denote something that is both a whole a piece in a larger whole; and I applied it to information.

The Information ideogram is an “i” (for "information"), composed as a circle or dot or point on top of a rectangle; inscribed in a triangle representing the metaphorical mountain. You may interpret the rectangle as a multitude of documents; and the point as the point of it all; and this ideogram as a way to point to the obvious—that without a point, thousands of printed pages are point-less!

Already this single source of insights, the Object Oriented Methodology, offers us some most fertile analogies to work with. One can program the computer in any sort of language that's sufficiently rich for that purpose—including the machine language, those zeros and ones that the computers "understand" and we humans don't. The creators of Object Oriented Methodology considered themselves accountable for the tools they gave to programmers! We university people too must now become accountable—for the information tools we gave to researchers! And to the people at large! The creators of the Object Oriented Methodology exercised this accountability by providing—a methodology. And that was what I did too, at the beginning of my knowledge federation work. The methodology allows us to explicate what, for instance, the word informed means; and what information needs to be like—so that we can be informed. But these details are beyond the scope of this brief sketch; I'll here only illustrate them by interpreting the Information ideogram.

You'll comprehend the mountain if you think of knowledge federation as a collective climb to a mountain top; so that we may rise above the tree tops and see the roads and where they lead; and what is the one we need to follow.

And you'll comprehend knowledge federation more precisely if you imagine the mountain as a structure of viewpoints; which offer coherent views (you can bend down and inspect a flower; or climb up the mountain and see the valley below; but never see both at the same time).

The information holon is offered as a structuring template and principle; and the mountain, which is technically called information holarchy, is composed of information holons—so that the points of more detailed holons serve as dots to be connected to compose those more general or high-level ones.

The key to it all is abstraction.

It is by recourse to abstraction that "information glut" is transformed into meaningful scopes and views; and into guidelines for meaningful action. The Information ideogram illustrates three kinds of abstraction:

- Horizontal abstraction, represented by the rectangle—which you'll comprehend if you think of looking at an object from a specific side

- Vertical abstraction, represented by the point—which you'll comprehend if you think of going up the mountain; toward the top, where the whole terrain is visible and the choice of direction is easy

- Structural abstraction, represented by the triangle or the mountain—which you'll comprehend if you consider how important it is to be able to consciously choose the ways—several ways—to look at an object; if your task is to see it whole.

The structural abstraction is what enable us to categorize; and configure and access information accordingly; as Neil Postman said we should do.

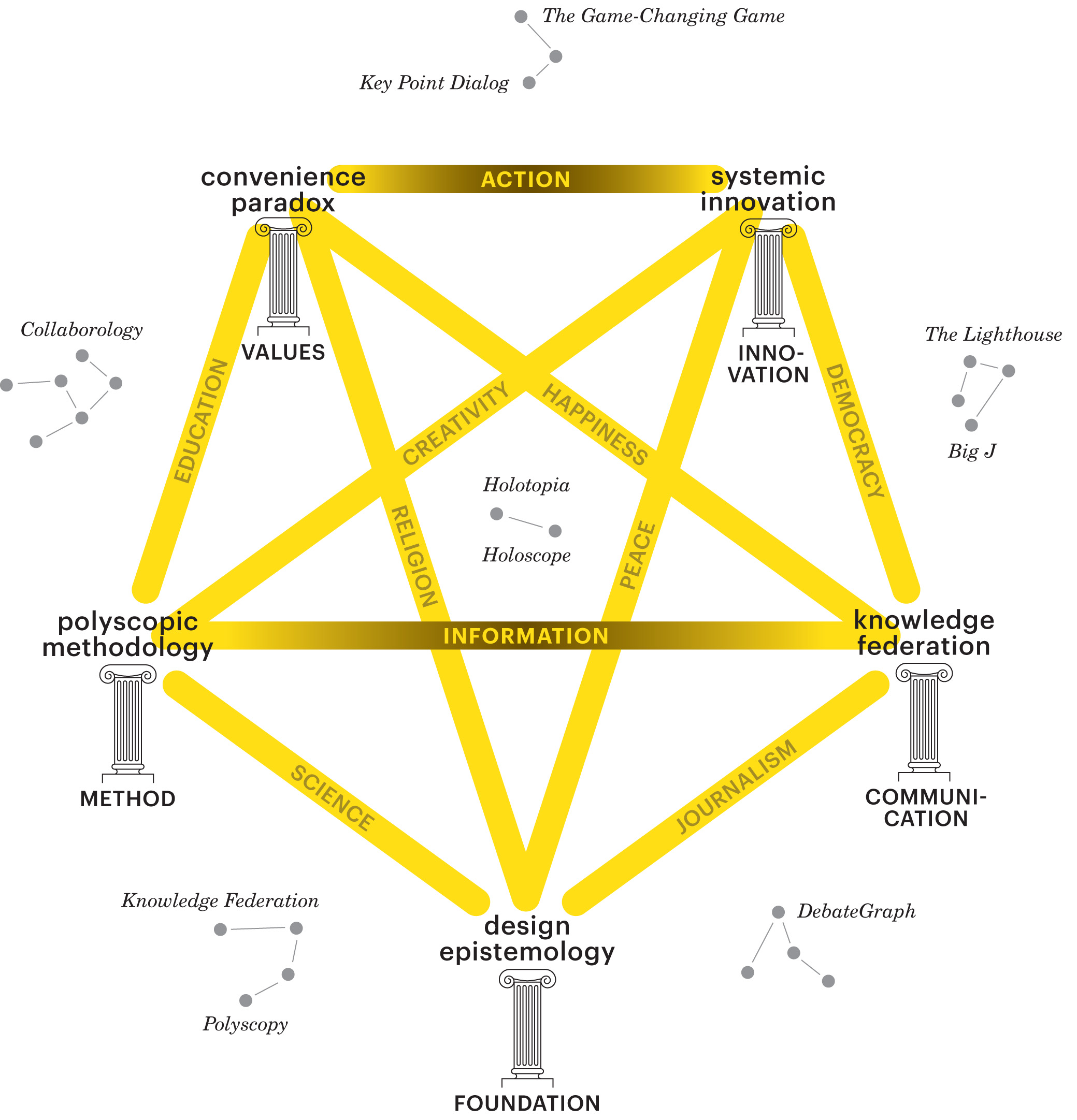

Holotopia ideogram shows what we'll see when proper light's been turned on.

Holotopia ideogram

The holotopia vision, which is depicted by the Holotopia ideogram, resulted from an experiment—where we did Postman suggested, and identified five pivotal categories; and for each of them collected and organized what's been academically published or otherwise reported; and condensed that to a point. Those five categories were:

- innovation—our technology-augmented capability to create, and induce change

- information—which by definition includes not only written documents, but all other forms of heritage or recorded human experience that may help us illuminate the course; and also the social processes by which information is created and put to use

- foundation—on which we develop knowledge; which decides what in our cultural heritage will continue to evolve—and what will be abandoned to decay

- method—by which we create knowledge; and distinguish knowledge from belief

- values—which direct "the pursuit of happiness" and our other pursuits.

The Holotopia ideogram comprises five pillars, each of which has a pivotal category as base and a point or insight as capital. Think of those pillars as elevating our comprehension of the corresponding category (by accounting for what's been academically published or otherwise reported) to a simple insight or point. In each case the resulting insight showed that the "conventional wisdom"—the way the category is ordinarily comprehended and handled—needs to be thoroughly revised and reversed.

The resulting five points or five insights elevate our comprehension of the world and our situation as a whole; so that when other similarly important themes such as creativity, religion and education are considered in the context of those five points—their comprehension and handling too ends up being revised and reversed; and we added ten themes to this ideogram—represented by the edges joining the five insights—to illustrate that.

Even more spectacular is the fact that—regarding each of those five pivotal categories—our overall situation, personal and societal or cultural, can be dramatically improved by reversing the way it's comprehended and handled; which turned holotopia into an uncommonly realistically optimistic future vision.

Furthermore, all the requisite changes are applications of a single general principle or rule of thumb—make things whole; which is, by the way, also the course of action the Modernity ideogram is pointing to (by showing us information as a functional element of the larger system of society; and how information needs to be adapted to its all-important function, so that the society can become functional or whole). The holotopia experiment showed that (not "success", nor "profit", but) making things whole is the direction we need to follow; that it is everyone's enlightened interest.

The stars on Holotopia ideogram stand for "reaching for the stars"—i.e. for the sort of achievements and changes that may now be unthinkable; which will be normal in the informed order of things that holotopia initiative undertakes to foster.

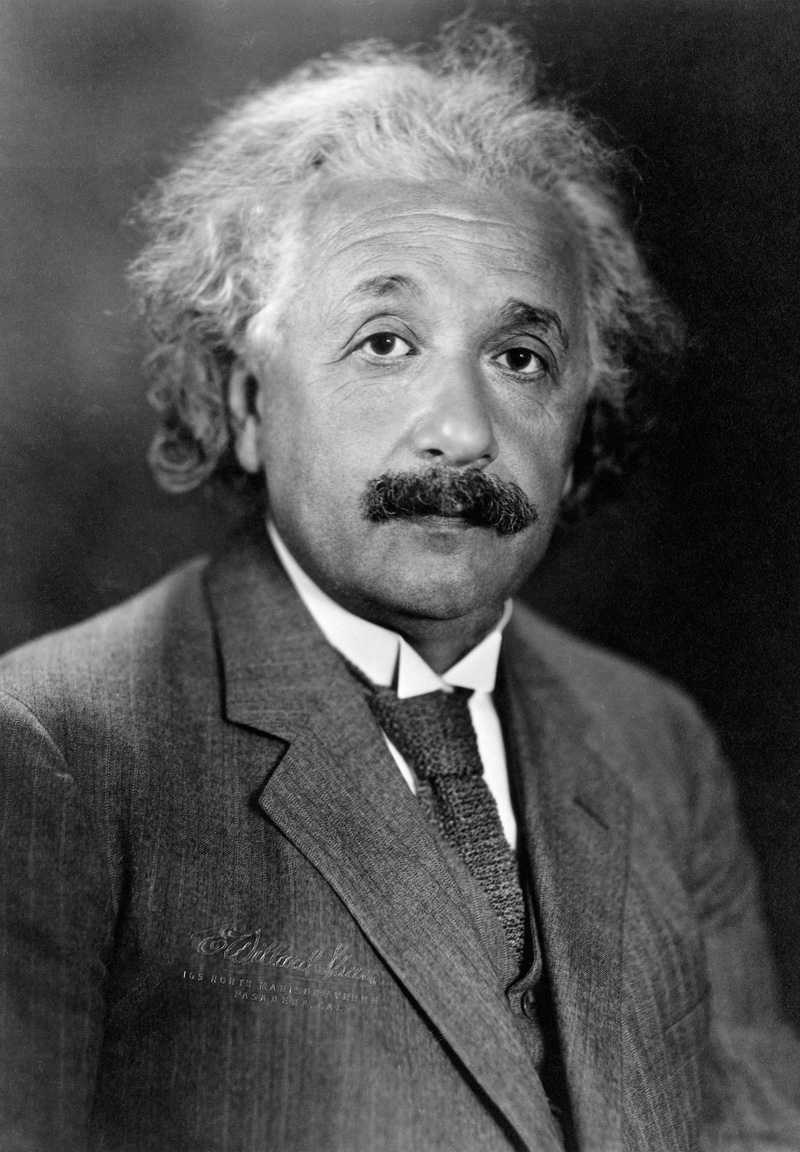

– A new type of thinking is essential if mankind is to survive and move toward higher levels.

(Albert Einstein in an interview to The New York Times, 1946)

My point

It stands to reason—and the holotopia experiment made it transparent—that this "new type of thinking" will need to be informed; we won't "move toward higher levels" by ignoring the results of science and other types of evidence.

But this is not my point.

My aim is not to tell you how the world is or how to correct it. I am not here to describe anything but to act and invite you to act; so that together we may foster the social process and be the social process that will supply the information we the people vitally need; which will restore vision to post-industrial democracy.

The key to requisite change is in our hands.

We, academic professionals, are looked upon to say what information needs to be like; and what's a good way to use the mind; and we even have education in our control!

The essence of my call to action is to change how we see ourselves.

So that instead of remaining "objective observers"—we acknowledge that we are the (core part of) society's 'headlights'; and self-organize as this vital and all-important function demands.