IMAGES

Contents

- 1 Federation Through Images

- 1.1 Not all images are worth one thousand words.

- 1.2 – Eppur si muove!

- 1.3 To make a case for a new academic paradigm, we revisit the assumptions that underlie our current ideas of what constitutes "good" knowledge and "good" academic work.

- 1.4 – On every university campus there is a Mirror.

- 1.5 – Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world.

- 1.6 – [The] flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science.

- 1.7 An up-to-date foundation for social creation of truth and meaning can be developed by relying consistently on truth by convention.

- 1.8 When we acknowledge as legitimate the view that the scientific language and method have been our own i.e. human creation, and that they limited what were were able to see and assert as true, it also becomes legitimate and even mandatory to adjust them so as to minimize that limitation.

- 1.9 – [T]he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

- 1.10 – It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier.

- 1.11 – The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it brings solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

- 1.12 When it was understood that the "Newton's Laws" were not a discovery of the inner workings of nature but his own creation and an approximation, two very different directions of development opened up to science.

- 1.13 – Enough of this. Newton, forgive me...

- 1.14 Why is our knowledge "growing downward"?

- 1.15 - We are no longer living in a traditional society.

- 1.16 How to enable knowledge to "grow upwards"?

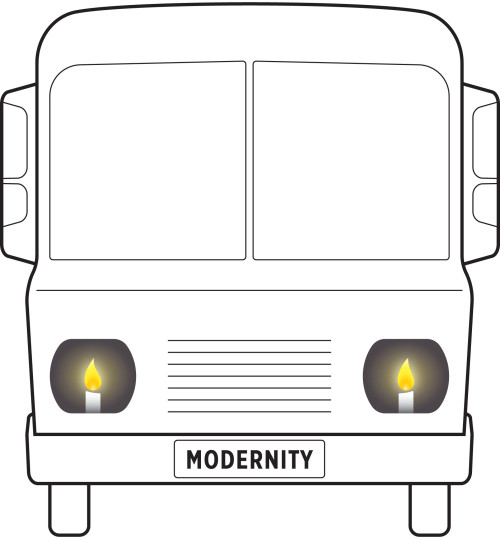

- 1.17 By representing the modern civilization as a bus and our traditional knowledge work as its candle headlights, the Modernity ideogram points to a course of action that modernity now requires to get back on track and acquire a viable new course of development.

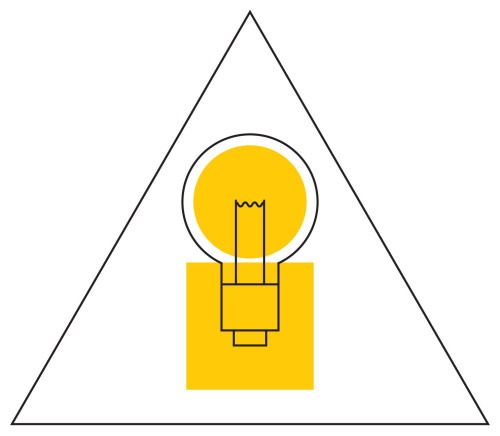

- 1.18 The task of Knowledge Federation is to prototype and evolve a socio-technical 'light bulb'.

Federation Through Images

Not all images are worth one thousand words.

But the ideograms are! They play a similar role in knowledge federation as mathematical formulas do in traditional science. An ideogram can condense a wealth of insights and many pages of text into an image whose message can be recognized at a glance. Recall the Newton's formula, or Einstein's ubiquitous E=mc² – those too are ideograms! But the possibilities behind the ideographic approach are endless and vastly surpass the conventional maths. Those possibilities vastly surpass also our illustrations; they are yet to be developed through creative use of new media.

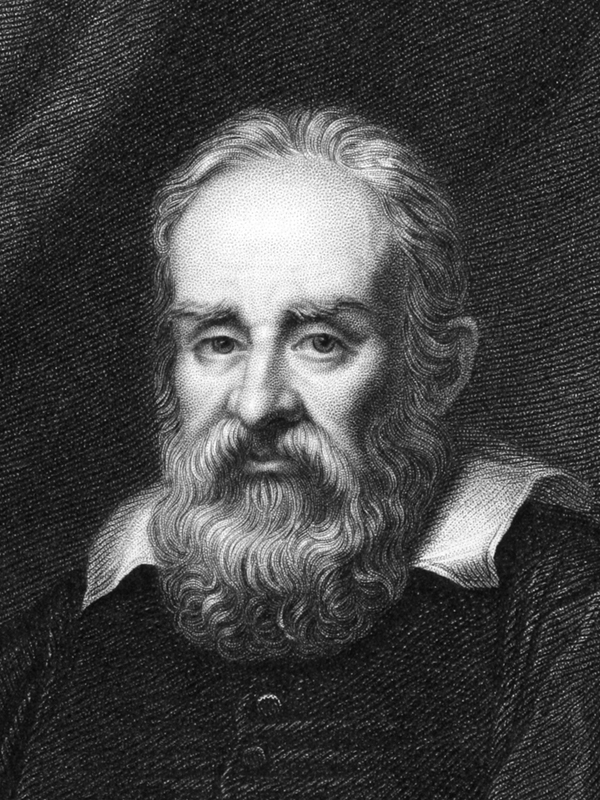

– Eppur si muove!

Be aware that what we are talking about is not at all "of philosophical interest" (only). To see why, think about the world of the Late Middle Ages: never-ending wars, horrifying epidemics, infamous Inquisition trials... Bring to mind the iconic image of Galilei in house prison, a century after Copernicus, whispering "Eppur si muove!" into his beard. The problems of the day were not solved by focusing on those problems, but by a slow and steady development of a whole new approach to knowledge. Several centuries of unprecedented progress followed. Could a similar advent be in store for us today?

To make a case for a new academic paradigm, we revisit the assumptions that underlie our current ideas of what constitutes "good" knowledge and "good" academic work.

No rational person will claim that knowledge should not be useful. And yet there are good reasons why practical skills such as cooking and automobile repair have not been admitted to the university. (At the University of Oslo, where this website is being hosted, even design and architecture have not been allowed to enter.) Since antiquity our ideas of what constitutes good knowledge and good knowledge work have been evolving, and they now find their foremost expression in science and philosophy. What we are about to see is that a completely new set of academic and more broadly knowledge-work practices is ready to emerge, with its own fundamental assumptions and values – which combines seamlessly pragmatic and fundamental concerns (or more simply, which empowers us to "make knowledge count") – because those fundamental assumptions and values reflect the current state-of-the-art insights in science and philosophy.

– On every university campus there is a Mirror.

We use the metaphor of the magical mirror (or more simply and humbly just "Mirror") to mark the entry point to an emerging and vibrantly novel approach to knowledge (which we may also call a paradigm, an alternate academic reality, a creative frontier, or a new way our society may create truth and meaning). What we will be talking talking about is a radical departure from the traditional idea of what constitutes "good" knowledge and knowledge work, as represented by the standard of excellence in the sciences: To obtain an academic license, we are disciplined to adhere to the language and the methods of an established academic discipline (by becoming "philosophy doctors"). We are then instructed to look at the world with the attitude of impartial, disinterested or "objective" observers. The rationale is that we then become able to depict the world as it truly is.

The Mirror symbolizes a profound insight that leads to a radical change of self-identity, attitude and values. "When we see ourselves in the Mirror", reads the explanation of this ideogram, "we see the same world that we see around us. But we also see ourselves in the world. We then realize that we are not the "objective observes" we believed we were – hovering above the world and taking snapshots through the objective of the scientific method. We are in the world! When we see ourselves in the Mirror, we recognize that it is us, humans, that have created the scientific method and the ethos of the disciplines. And that we have also created the world we see around us, by looking at it in a certain way. Armed with those insights, we cannot but feel responsible for the world, for the way we look at at the world, and the way we instruct others to look at the world.

As the case is in Louis Carroll's familiar story from which the mirror metaphor has been borrowed, it is possible to walk right through the magical mirror. And when one does, one finds himself in an entirely different academic reality. As in the story, this new reality is in a number of ways a reverse image of the reality we've grown accustomed to.

You may think of knowledge federation as a model or a prototype of that other academic or more generally creative reality. What we will be talking about here are its philosophical or methodological underpinnings.

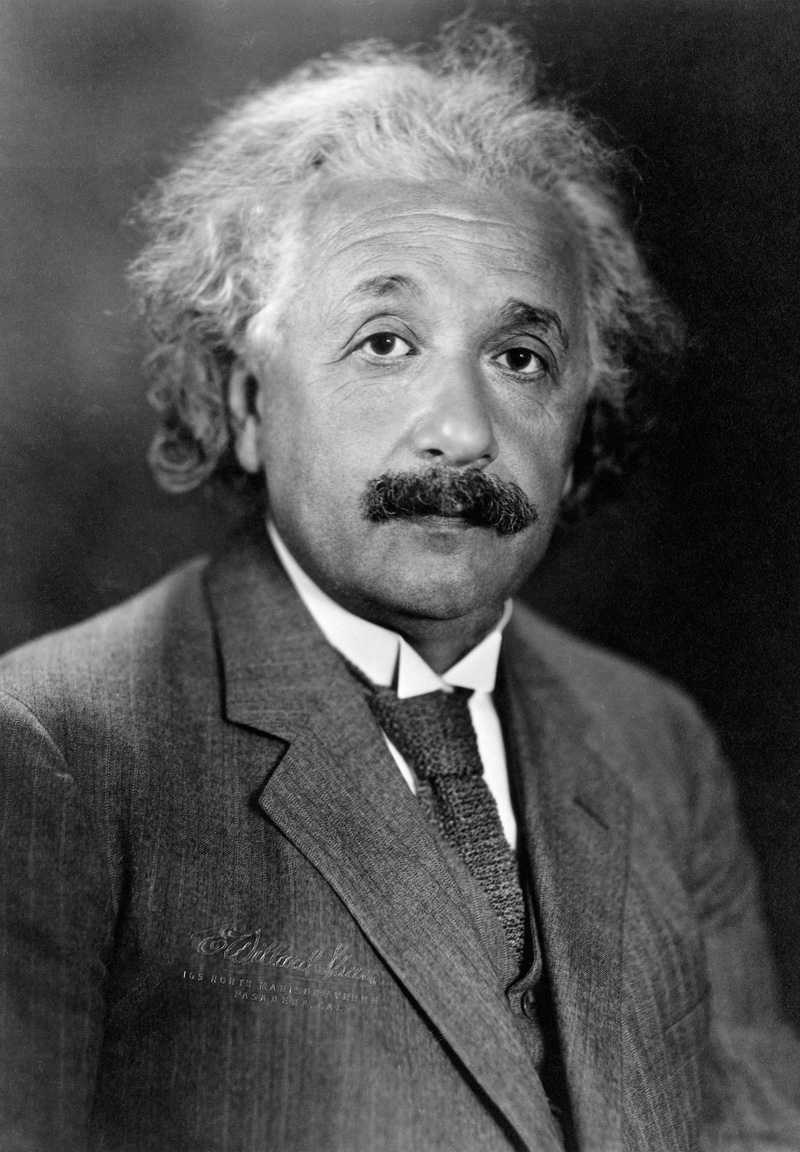

– Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world.

There are too many giants on whose shoulders we may to stand to see the Mirror. Hence we here represent them by a single one, Albert Einstein. Also elsewhere on these pages Einstein will appear in the role of the icon for "modern science". "Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world," Einstein and Infeld wrote in Evolution of Physics. "In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison."

What we've just heard was 'modern science' telling us that the "correspondence with reality" is a criterion that simply cannot be verified. What we'll hear next is 'modern science' telling us that the common inner conviction that our ideas correspond with reality is a common result of illusion: "During philosophy’s childhood it was rather generally believed that it is possible to find everything which can be known by means of mere reflection. (...) Someone, indeed, might even raise the question whether, without something of this illusion, anything really great can be achieved in the realm of philosophical thought – but we do not wish to ask this question. This more aristocratic illusion concerning the unlimited penetrative power of thought has as its counterpart the more plebeian illusion of naïve realism, according to which things “are” as they are perceived by us through our senses. This illusion dominates the daily life of men and animals; it is also the point of departure in all the sciences, especially of the natural sciences.”

If the aim of our activity and of the underlying methodology is to distinguish what is "really true" from illusion – how can it rely on a criterion that is impossible to verify? And which is itself a result of illusion?

– [The] flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science.

"We are not discovering an objectively true picture of reality. We are constructing (an approximate representation of) reality". This conclusion, which we are calling the constructivist credo, follows from the results reached in a broad variety of disciplines (physics, biology of perception, cognitive science, linguistics, sociology, philosophy...). It is also an epistemological position that was upheld explicitly or implicitly by the 20th century's giants.

But this epistemological position has a problem. When the constructivist credo is placed into a system of thought where "truth" means "correspondence with reality", and where each statement is supposed to be about reality, the result is a paradox.

Fortunately, there is a solution. It is what Willard Van Orman Quine called truth by convention. Truth by convention is the kind of truth that is common in mathematics: "Let x be... Then..." It is meaningless to ask whether x "really is" as stated. In "Truth by Convention", Quine argued that "every science" progresses from an assumption of mutual understanding and reality of the shared concepts, to realizing that this assumption does not hold, and then resorting to explicit definition by convention.

So why not allow knowledge work at large to progress similarly?

An up-to-date foundation for social creation of truth and meaning can be developed by relying consistently on truth by convention.

A practical way to do that is to spell out rules – to specify the underlying assumptions by stating them as a convention. We have done that exercise; the result is a prototype called the Polyscopic Modeling methodology. The knowledge work (epistemology, methods, information formats, results, insights...) that results from applying this methodology is called polyscopy. We often use this shorter and simpler keyword also for the methodology itself.

You may now imagine knowledge federation as a liberated academic territory made available and divided from the conventional academic reality by the magical mirror – liberated from the dictate that to receive the academic quality stamp, creative work must conform to one of the hereditary one-way disciplinary routines. Liberated from the reification that "science" means what the scientists have been doing for centuries. This does not mean, however, that the academic reality on the other side of the Mirror departs from the heritage and the results and insights reached in the sciences. On the contrary! As we shall see, the academic reality on the other side of the Mirror is a direct continuation and implementation of those insights and results. The reality on the other side of the Mirror is free in the sense – and only in the sense – that what is understood and honored as "good" knowledge is consistent with the good knowledge we already own about knowledge itself! Our value proposition, where we find our creative niche, it's that since the conventional-academic scheme of things evolved as the approach to truth and reality, it has not developed the provisions for updating itself when the results of the sciences itself demand that. It is that capability that knowledge federation has endeavored to add to our academic work, and more generally to knowledge work and to creative work – the capability of our creative institutions to re-create themselves.

The results of polyscopy show that when the constructivist credo is stated as a convention, it becomes a solid foundation for a an approach to knowledge that satisfies both the logical (consistency) and pragmatic (usefulness) criteria!

And since knowledge federation is to a large degree motivated by the potential of "digital technology" to "help make this a better world" (see Federation through Stories), let us not forget to highlight the following: When the contemporary media technology is applied to merely (and radically!) increase the efficiency of the traditional practices and patterns of interaction in knowledge work, what the people are already doing, the natural result is information glut. When, however, we are allowed to reconstruct what knowledge work is "from scratch" and how it operates (based on the available epistemological and methodological insights, and the contemporary needs of people and society i.e. what information needs to be like to help us jointly realize whatever we need to know), then radically more innovative and dramatically more useful ways to develop and apply the information technology become readily available.

You may now understand the knowledge federation prototype (which includes polyscopy as its academic or methodological foundation) as a piece of evidence, or as a central element of the case we are now presenting, for recognizing and establishing and conscientiously developing and globally scaling the way of thinking and working it represents.</p>When we acknowledge as legitimate the view that the scientific language and method have been our own i.e. human creation, and that they limited what were were able to see and assert as true, it also becomes legitimate and even mandatory to adjust them so as to minimize that limitation.

The first reversal on the other side of the metaphorical Mirror is of the way the language and the method are understood and handled.

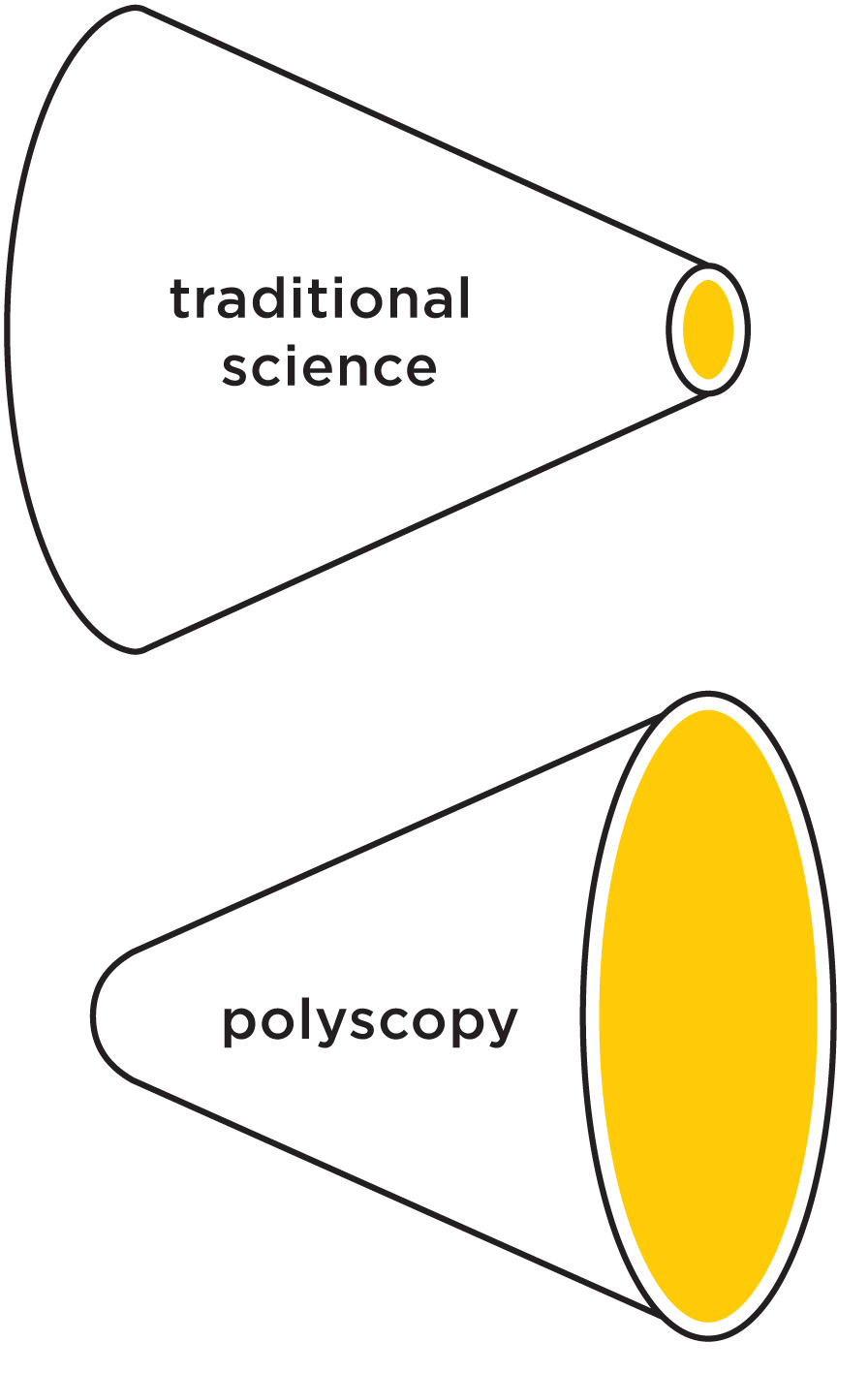

This reversal is so germane to polyscopy that we are calling the ideogram that represents it the Polyscopy ideogram. Our design team simplified this ideogram by deleting the eye we originally had on the left-hand side of each of the conic tubes, to suggest that they represent "ways of looking". In polyscopy the ways of looking are called scopes. As the name suggests, it is the central notion of polyscopy. The idea represented by the ideogram is that when we've identified something as our own way of looking or scope, it becomes natural to adjust it so that we may see more, see what needs to be seen, and also see it in ways that make the meaning and nature of what is looked at transparent to the people who may need to benefit from it. In polyscopy (by convention), the language and the methods in knowledge work, and even the results of knowledge work, are considered as no more than human-created and hence re-creatable ways of looking at things or scopes.

In polyscopy the terms of the language can be freely created by convention. We call them keywords, and when we want to emphasize that a concept is intended to be interpreted as defined, we italicize it. This enables us to create precise and even rigorous ways to look at any chosen theme. Furthermore we not only do not impose a fixed way of looking at things, but we indeed consider it an obligation, a core part of the task, to explain or justify the scope (why have we chosen to look at the given theme, and why in exactly those specific ways).

The Polyscopic Modeling methodology is conceived as a general-purpose methodology – it allows us to create or federate insights and ideas about any subject, and at any level of generality or abstraction. Hence instead of choosing our subject of study according to the habitual areas of interest and language and method of a discipline, we become free to direct our attention and to prioritize our interests by other concern, such as their relevance to knowledge work, and to society – and we shall see how in more detail below.

This reversal includes the very meaning of information. If we are not claiming the reality of our models – what is really their meaning, and function? The answer is that they are scopes – ways of looking, which we share with one another to see differently, more or better. And above all – to see what needs to be seen.

The reversal pointed to by the Polyscopy ideogram includes even the attitude we have toward claims and ideas. Instead of rejecting whatever fails to agree with our dominant worldview, and devising ways to convince or coerce trespassers (peer reviews, debates...), our attitude becomes the one of the dialog – which means that we suspend judgement and keep at bay own propensity to reject and criticize, which is on the other side of the Mirror understood as an impediment to communication, and to free creative work in general. We do our best to see things in a new way, by using the offered scope. Contradictory ideas are allowed to co-exist in the same knowledge-work space. Indeed knowledge federation is conceived as a suitable and continuously evolving set of practices and social processes, which amount to "collective thinking" – by which the veracity, relevance and compatibility of the stated ideas are continuously brought into relationships and re-evaluated and re-negotiated.

– [T]he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people.

Turning now to the giants whose insights might justify and legitimize this reversal, we once again find too many. We here represent them by only two, and we weave their statements together in such a way that the core sides of this all-important issue are at least touched upon – and we let you draw your own conclusions. An additional observation of a giant is be added as an epitaph and a curiosity.

In his 1958 book-essay "Physics and Philosophy" Werner Heisenberg explained how "The nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people. (...) This frame was so narrow and rigid that it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our language that had always belonged to its very substance, for instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul, or of life." The entire monograph is an historical account explaining how this worldview become dominant, and how the modern physics rigorously disproved it. Heisenberg concludes that "one may say that the most important change brought about by the results of modern physics consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century".

– It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier.

Benjamin Lee Whorf diagnosed the resulting situation as follows (already in the 1940s!): "It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier. Either it must bury its dead, close its ranks, and go forward into a landscape of increasing strangeness, replete with things shocking to a culture-trammelled understanding, or it must become, in Claude Houghton’s expressive phrase, the plagiarist of its own past."

– The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it brings solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

René Descartes is often "credited" as the philosophical father of the limiting (reductionistic) side of science. This Rule 1 from his manuscript "Rules for the Direction of the Mind" (unfinished during his lifetime and published posthumously) shows that even Descartes might have rather be remembered as an early supporter of polyscopy.

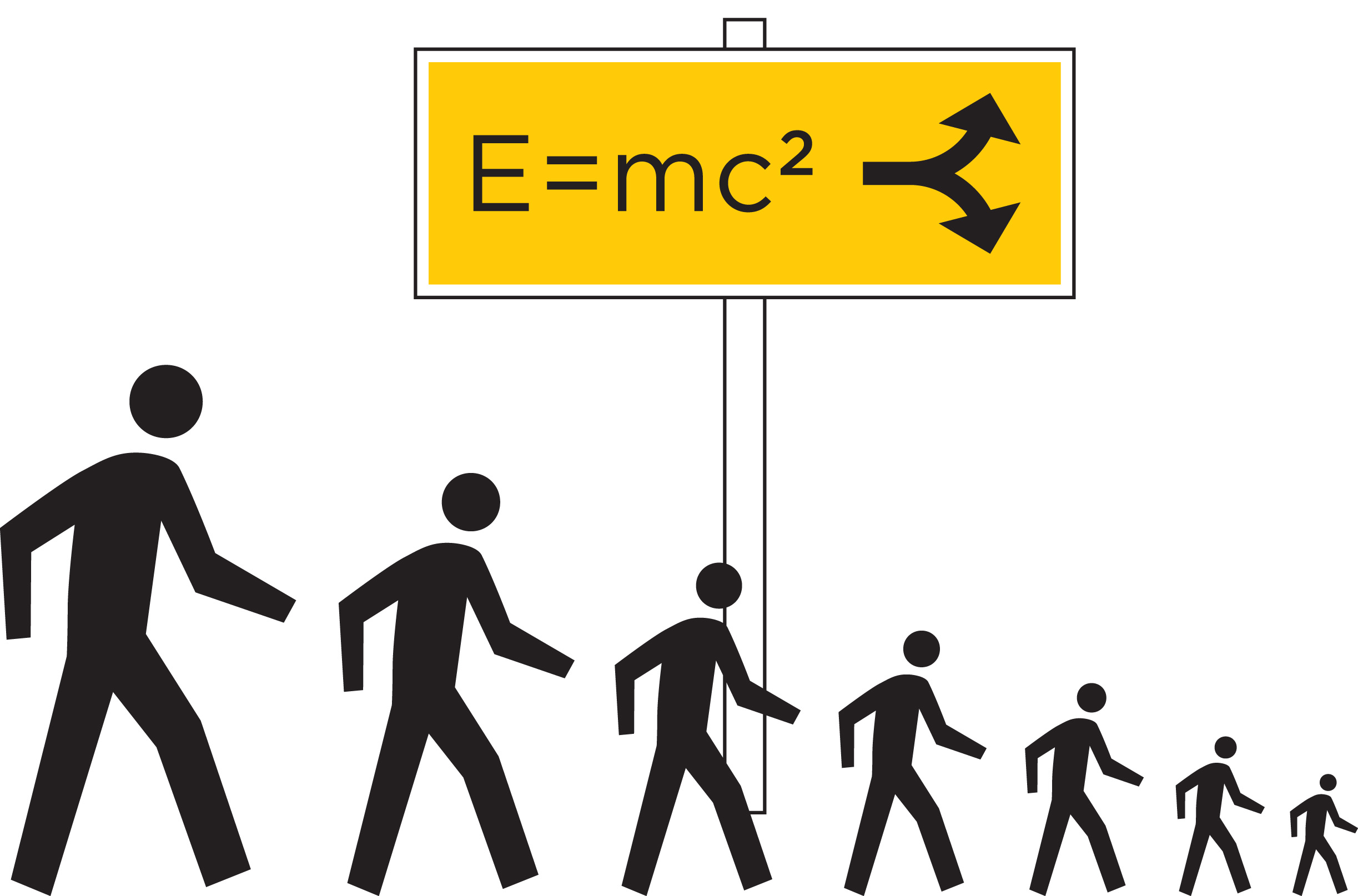

When it was understood that the "Newton's Laws" were not a discovery of the inner workings of nature but his own creation and an approximation, two very different directions of development opened up to science.

The second reversal is of the direction in which knowledge is growing.

The vertical axis and the direction "up" have a distinguished role in polyscopy. The direction "up" symbolizes what is technically called "vertical abstraction", the result of which is a general insight, principle, rule of thumb... When we 'go up', we see, metaphorically speaking, the forest but not the trees. Hence we become able to see where we are headed, and whether there might be a much better way to go available to us. The direction "up" also symbolizes drawing nearer to basic practical human concerns.

And now about the message of this ideogram: When it was understood that the "Newton's Laws" were not a discovery of the inner workings of nature but his own creation and an approximation, two directions of development opened up to science. One direction was to grow science "downwards" – away from daily-life concepts and concerns, and toward greater rigor, precision and detail. The other direction was "upwards" – by doing in all walks of life what Newton did in physics, namely by creating approximate concepts and models that can vastly improve our understanding, and suitably orient our action. The sequence of scientists "converging to zero" in the ideogram is there to indicate that only the former option was followed...

– Enough of this. Newton, forgive me...

Here a single text will provide sufficient illustration and support – Einstein's "Autobiographical Notes". In a similar way as Heisenberg did in Physics and Philosophy, Einstein first describes the successes of science that resulted by following the classical or Newton's way. Then he points to the discrepancies or anomalies, the phenomena that could not be explained in that way, and that needed completely new thinking. Einstein concludes: "Enough of this. Newton, forgive me; you found just about the only way possible in your age for a man of highest reasoning and creative power. The concepts that you created are even today still guiding our thinking in physics, although we now know that they will have to be replaced by others further removed from the sphere of immediate experience, if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships."

Why is our knowledge "growing downward"?

Observe that "upward" is a good direction for knowledge to grow as well – toward general insights that cover many specific cases, that are easily and widely understandable rather than obscure, that respond to basic human interests and needs, that are general principles from which specific details follow as a consequence...). How in the world did this got reversed?

To really see the answer we would need to revisit the history, and here we only give a brief hint. First of all notice that knowledge federation (understood as making connections and valuations, creating a coherent big picture etc.) is what knowledge work is really all about. So traditional science too may be understood as a specific way to federate knowledge – by completing a coherent representation of the basic mechanism of nature, how it all works... The nature of our situation – the key point, the insight that compelled an impressive array of giants to speak out (Einstein in Autobiographical Notes; Heisenberg in Physics and Philosophy; Oppenheimer in Uncommon Sense; Feynman in The Character of Physical Law...) – is that this approach to truth and knowledge was so successful, that it naturally became the academic and even cultural standard.

So quite naturally science organized itself as an undertaking to explore and map the workings of nature, all the way to "the bottom".

There are three kinds of disadvantages of the traditional-scientific approach to knowledge (federation):

- Evidence goes against the assumption that the underlying model will eventually be completed (there are good reasons to believe that it cannot). Let's leave a proper analysis for another occasion and provide only two hints: (1) the nature is not a mechanism (that's essentially the message that modern physics has given us...); (2) the splitting of the atom is a good metaphor for this situation: the etymological meaning of "atom" is "indivisible" – it was supposed to be the ultimate particle of matter in terms of which the larger things could be described. So when the molecules and atoms were scientifically discovered, the scientists naturally said "well, here it is!" But the atom did get divided – first into electrons, protons and neutrons, and with time into more than one hundred "subatomic particles". Today the atom is Humpty Dumpty that nobody can put back together again... Our causal explanation of "how it all works" turned out to be retreating downwards, just when it appeared to be within our grip...

- The second reason is complexity – understood now in several ways including complex dynamic systems, computational complexity... The point here is that even if we could create a complete model, the interesting consequences would not follow from it; they would probably not even be computable from its mathematical description.

- And finally and most importantly – the knowledge we now most urgently and even vitally need is not at all of the "how it all works" kind; and this knowledge will not come into being even if we did find a complete representation of how it all works, and computed its consequences...</em>

</ul>

Revisiting Einstein's Autobiographical Notes will give us some additional insights. Einstein describes how the classical science, and specifically the Newton's Laws, turned out to be so successful in explaining the natural phenomena, that it became natural to believe that all of nature would soon be understood in a similarly clear and predictable way, just as we might understand the workings of a clockwork. And when it turned out that the things were not at all that simple, at that point the division and organization of the academic or more generally creative work had already taken place. Einstein, naturally, considered himself "a physicist". Following the other direction was nobody's job!

Notice that what we are talking about is not only a matter of high practical importance, but also a deeper issue of the academic self-perception and self-identity, which is the core theme pointed to by the Mirror. At this deeper level, those two directions of growth represent two ways of defining what "good" knowledge and "good" knowledge work represent. One means doing what Newton did – namely modeling physical phenomena in terms of "physics concepts" such as mass, velocity etc. The other means allowing ourselves to do as Newton did – and create concepts and methods to model, approximately but precisely enough, whatever under the Sun may need our (that is, people's) attention and understanding.

- We are no longer living in a traditional society.

It is time now to put on our map another category of giants – the ones from the humanities. Let them here, for now, be represented by Anthony Giddens, and more specifically by his keyword "reflexive modernity". The point will be that our society is changing and has already changed. And that in this new situation solid, explicit knowledge on which we could rely to understand situations and issues, has now a key role that was not there previously. Here are some comments of Giddens' work we found on the Web: "It is important for understanding Giddens to note his interest in the increasingly post-traditional nature of society. When tradition dominates, individual actions do not have to be analysed and thought about so much, because choices are already prescribed by the traditions and customs. [...]. In post-traditional times, however, [...] all questions of how to behave in society [...] become matters which we have to consider and make decisions about. Society becomes much more reflexive and aware of its own precariously constructed state. Giddens is fascinated by the growing amounts of reflexivity in all aspects of society, from formal government at one end of the scale to intimate sexual relationships at the other."

How to enable knowledge to "grow upwards"?

The answer is "by creating suitable criteria", and stating them a part of the definition of the methodology – i.e. as a convention. And then of course by providing suitable methods by which the creation of high-level concepts, insights and results is made possible.

The notion of gestalt has here a central role. The gestalt is our interpretation of a situation (and importantly of the situation we are in), which points to a correct course of action. "Our house is on fire" is a textbook example. By definition (i.e. by convention), having a correct gestalt is what "being informed" is about. Knowledge federation provides suitable methods and social processes by which this goal can be achieved – examples of which are presented on this website. A more comprehensive account of the methods and further examples can be found in the linked documents.

By representing the modern civilization as a bus and our traditional knowledge work as its candle headlights, the Modernity ideogram points to a course of action that modernity now requires to get back on track and acquire a viable new course of development.

The third and last reversal is the reversal of the purpose of creative work, for which our technical keyword is epistemology.

The Modernity ideogram has two key roles in our proposed prototype. One of them is to serve as an ideographic representation of a gestalt – and hence of a result. In this role its message is that the situation we are in They are distinct, but at this level of generality we may consider them as synonymous, because what we are interested in is the BIG point they have in common – and that is what this ideogram is there to express. The point is... that by changing the headlights we make THE WHOLE BIG THING radically more valuable (turning it from risky, potentially a mass suicide machine, to a vehicle that can take us to places where we may reasonably want to be). Notice that when we consider the information as a commodity (as the media informing does), or when we create it within the limits of a discipline (as it is common in academic research), we are not likely to do the kind of big structural change that is suggested by the transition from the candle to the light bulb.

But what interests us here is the epistemology. The bus represents our technologically advanced and fast-moving civilisation. The candle headlights represent the way information is created and used, which we have indiscriminately inherited from the past. As a practical message, this image suggests that the ways of creating and sharing information we have inherited will not fulfil some of the purposes we now urgently need to take care of, notably the purpose of orienting our choices, or of 'illuminating the way'. By designing instead of inheriting what we do with information, suggests this image, we can now make the difference between a hazardous ride into the future, and using our technology to take us to places or conditions where we may justifiably wish to be.

In an academic or fundamental sense, the bus metaphor is pointing to an epistemological stance where information is no longer considered an objective image of reality, but as a part of this reality, or a system within a system, whose purpose is to fulfil certain specific roles. Under this epistemology, the creative acts to reconfigure what we do with information become basic research – as “the discovery of natural laws” has been in traditional science. The bus metaphor further points to the necessity of what we are calling systemic innovation, where we apply our creative capabilities, and our technology, to fulfil the purposes that must be served, rather than to reproduce the habitual practices and ways of working. The bus points to the need to turn our basic institutions or socio-technical “candles” into “lightbulbs”, and to the opportunity to invent and create on this larger, systemic scale. By doing that, suggests the bus metaphor, we may make a similar difference in the ream of our institution as the conventional innovation made by designing technical objects, since the age of the candle.

The task of Knowledge Federation is to prototype and evolve a socio-technical 'light bulb'.

The “i” in the above metaphorical image, composed of a circle on top of a square, renders the information that Knowledge Federation undertakes to create in a nutshell. The purpose of this information is to provide direction-setting high-level insights (represented by the circle), based on a multiplicity of lower-level insights (represented by the square), which illuminate an issue or phenomenon from multiple sides.

What is being shared here – and you may watch it evolve and emerge through time – is the third book of the Knowledge Federation Trilogy titled "Knowledge Federation" and subtitled "Science for the Third Millennium". The idea is to render an academically sound and convincing argument – in an entertaining and engaging cartoon-like format – that "science" (what we collectively rely on to provide us truth and meaning) must become something entirely different than what it presently is.