IMAGES

Contents

Federation through Images

What should knowledge be like?

The way we handle knowledge is historical and accidental

Perhaps no rational person would argue that knowledge should not be useful; or that information should not provide us the big picture and general, direction-setting insights, but only details.

There is, however, a reason why we don't have a culture of big-picture knowledge – and that reason is historical.

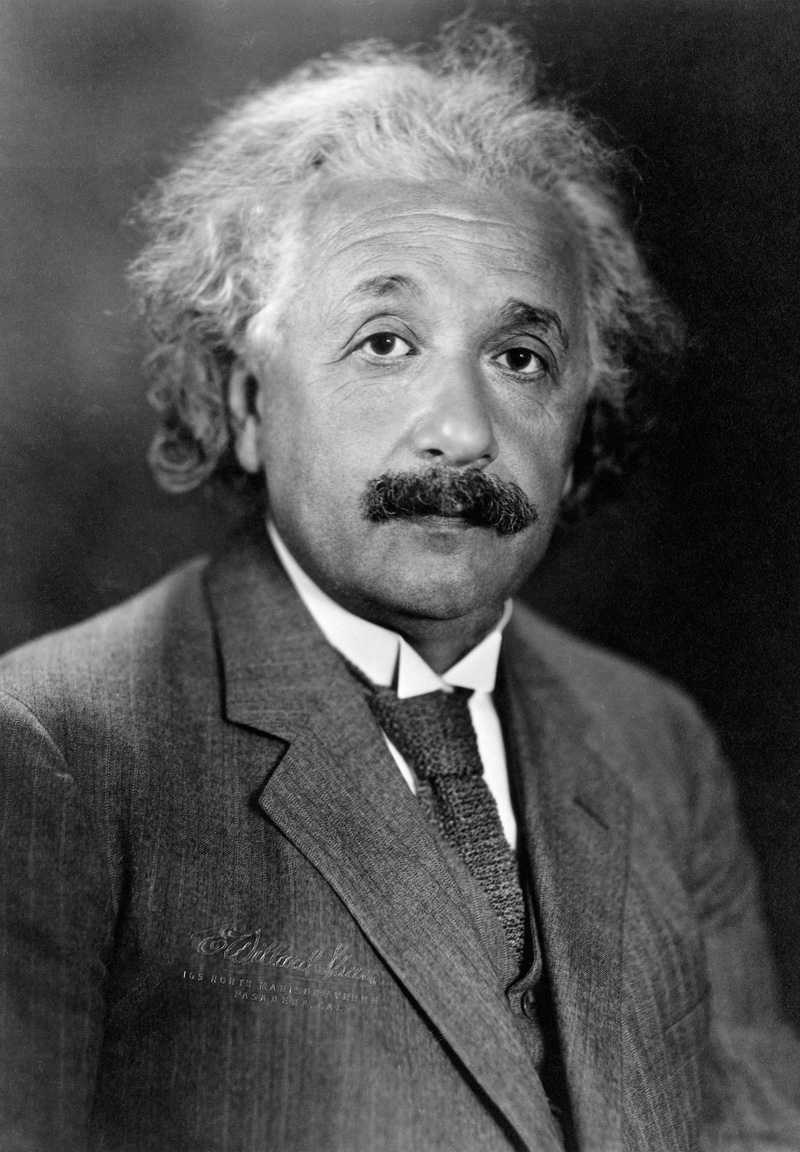

In spite of all the fruitfulness on particulars, dogmatic rigidity prevailed on the matter of principles: In the beginning (if there was such a thing), God created Newton's laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces. This is all; everything beyond this follows from the development of appropriate mathematical methods by means of deduction.

This familiar quote (where Einstein describes how he saw physics at the point when he entered it as a graduate student, around the turn of the century) will serve for a very succinct summary of that history, and of our contemporary position in it.

Necessarily, as Einstein suggested (and after all it's evolution we are talking about, and evolution takes time), early science inherited some of the mindset of the culture out of which it developed. And furthermore, as Einstein described in the remainder of the same text, science was so successful in both explaining the natural phenomena and changing the human condition, that it naturally appeared as the discovery of the inner workings of nature. And of the reality as it truly is.

And then it all exploded – with the bomb that fell on Hiroshima! The mass, and the matter itself, turned out to be just another form of energy. And even the passage of time – however objectively given it might have appeared to our intuition – turned out to be relative.

The future of knowledge is in our hands

What we are about to see is that the insights that have been reached through the experience of modern physics empower us to develop a new foundation for the creation of truth and meaning – which is both academically rigorous and yields the kind of knowledge we urgently need.

These images are ideograms

Pictures that are worth one thousand words

Not all pictures are worth one thousand words; but these ideograms are!

Repurposing science

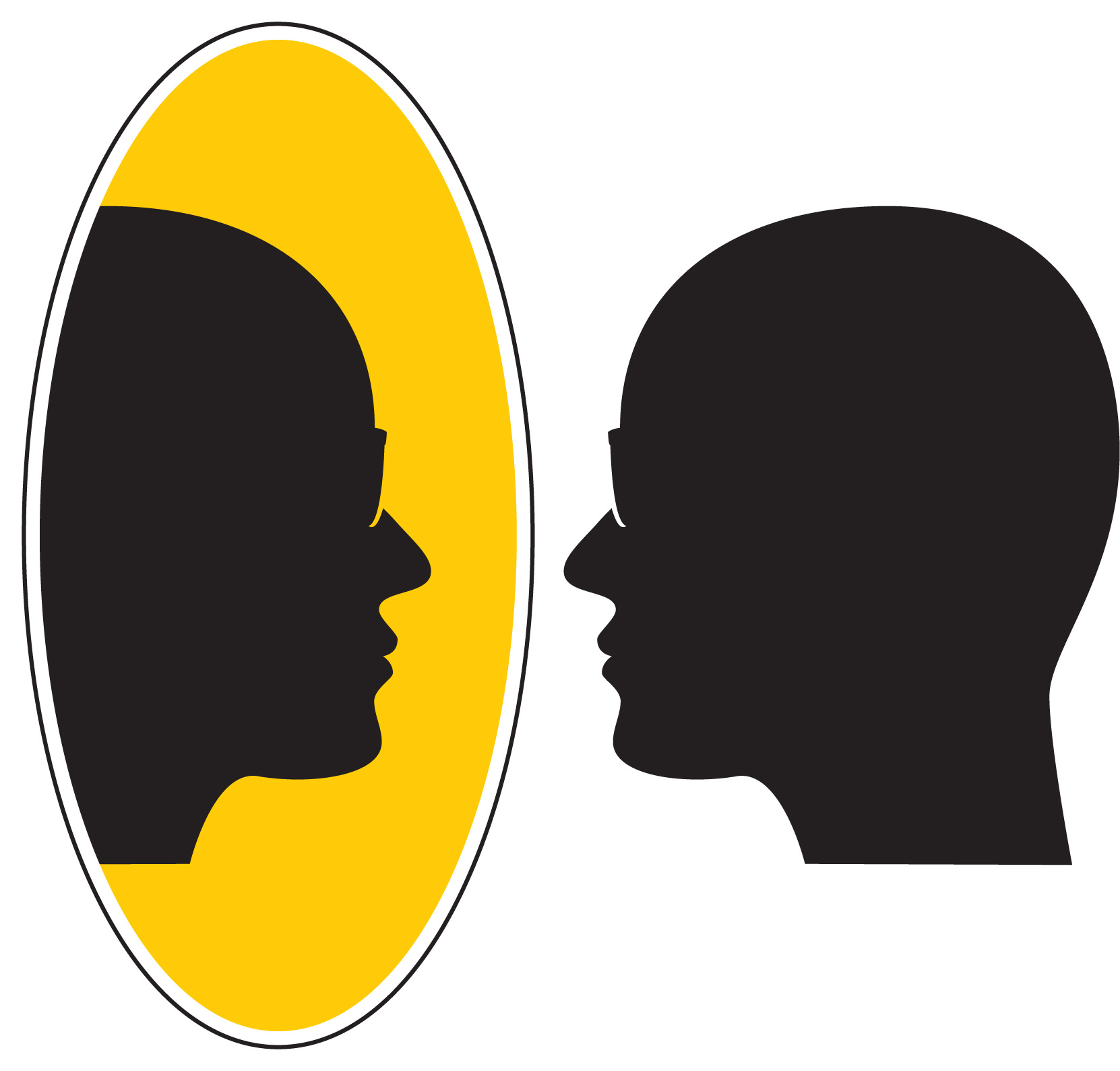

The academic mirror

On every university campus there is a mirror. Busy with article deadlines and courses, we do not normally see it. But it is there! When we see ourselves in this mirror, we see the same world that we see around us. But we also see ourselves in the world.

The mirror here represents the insight, reached in so many ways in 20th century's science and philosophy (see Federation through Stories), that we cannot really build our knowledge work solidly on the age-old assumption that the purpose of knowledge is to mirror reality "objectively", as it truly is.

When we see ourselves in this mirror, we see that it is really us that have created both our knowledge and our knowledge work. We realize that we are not disembodied spirits hovering over the world and looking at it objectively – but people living in the world, and responsible for it.

As the case is in Louis Carroll's familiar story, this academic mirror too can be walked right through! And when we do that, we find ourselves in an entirely different academic reality. (You may now understand Knowledge federation as a model or prototype of that reality.)

We cannot really know reality

Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world. In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison.This often quoted excerpt from Einstein and Infeld's Evolution of Physics will suggest to us that all we are really doing – and can do – is making models. And that it would be hard to even imagine a procedure by which we could confirm that our models correspond to the real thing.

This second excerpt, from Einstein's comments on Bertrand Russell's Theory of Knowledge, will suggest that our common belief that our representations correspond to reality has largely been based on illusions.During philosophy’s childhood it was rather generally believed that it is possible to find everything which can be known by means of mere reflection. (...) Someone, indeed, might even raise the question whether, without something of this illusion, anything really great can be achieved in the realm of philosophical thought – but we do not wish to ask this question. This more aristocratic illusion concerning the unlimited penetrative power of thought has as its counterpart the more plebeian illusion of naïve realism, according to which things “are” as they are perceived by us through our senses. This illusion dominates the daily life of men and animals; it is also the point of departure in all the sciences, especially of the natural sciences.

But if our goal is is to distinguish truth from illusion – how can we rely on a criterion that is impossible to verify? And whose positive indications themselves tend to be results of illusion?

A new foundation for knowledge

We emphasize that the new foundation we are proposing does not depend on what's just been said. Even if depicting reality in an objective way were possible; and even if science really did that – even then this way of founding knowledge would be rigorous.

The reason is that this new foundation is independent of the very notion of reality. It simply circumvents it altogether.

This is done by resorting to what Villard Van Orman Quine called truth by convention. It's the kind of truth that is common in mathematics: "Let x be... Then..." It is meaningless to ask whether x "really is" as stated. In "Truth by Convention", Quine posits that

So why not allow knowledge work at large to progress in that same manner?The less a science has advanced, the more its terminology tends to rest on an uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. With increase of rigor this basis is replaced piecemeal by the introduction of definitions. The interrelationships recruited for these definitions gain the status of analytic principles; what was once regarded as a theory about the world becomes reconstrued as a convention of language. Thus it is that some flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science.

What makes 'the magic' possible, of 'walking through the mirror', is that the truth on the other side is (by convention) the truth by convention. We call this basic convention the methodology.

By creating a methodology, the age-old preoccupation with truth and reality is established on the academic terrain that Herbert Simon called "the sciences of the artificial" – which is of course just a technical term for our metaphorical reality on the other side of the mirror.

The sciences of the artificial, according to Simon, do not study what objectively exists in the natural world – but man-made things, with the goal of adapting them to the purposes they serve in the human world.

Spelling out the rules

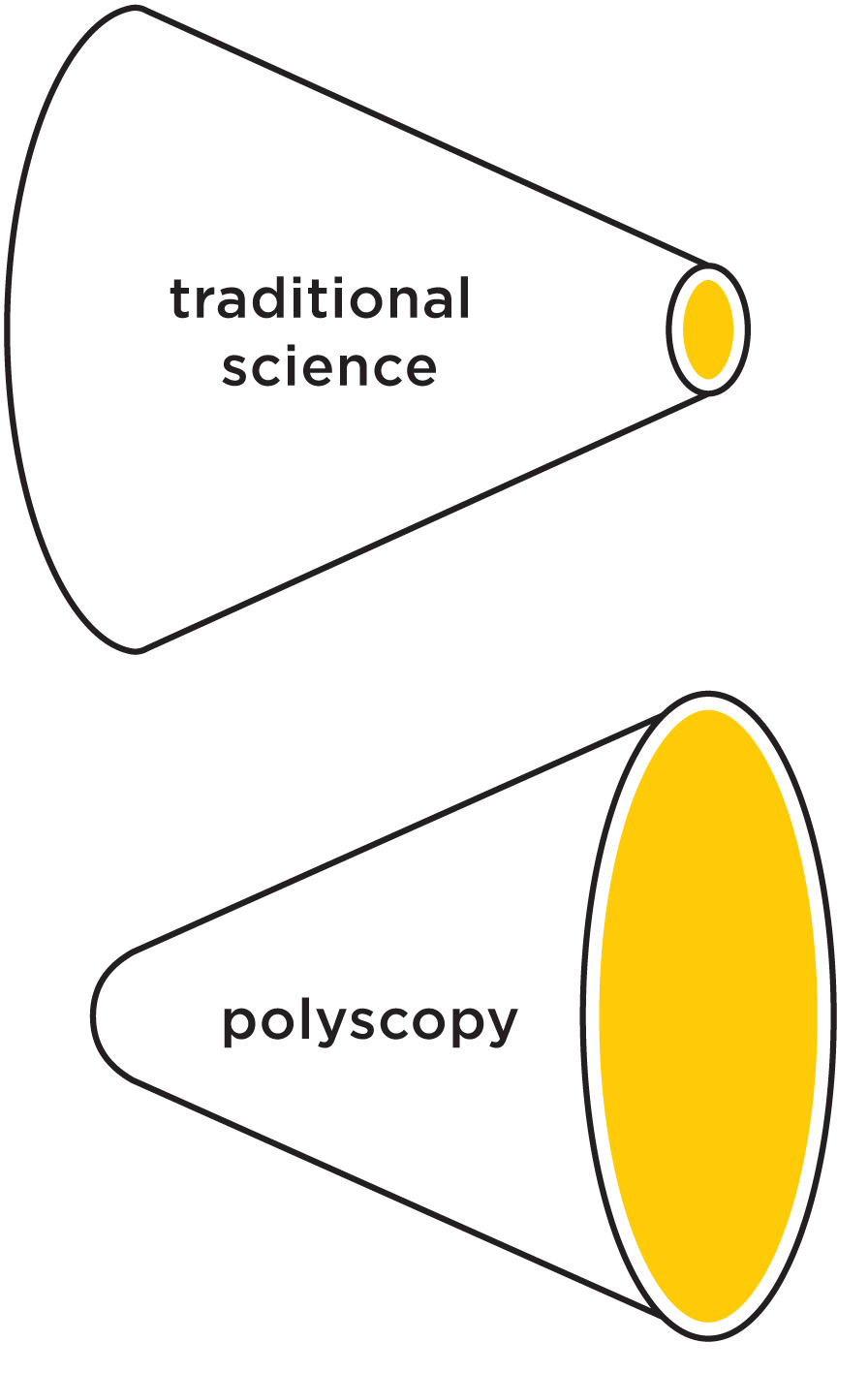

The prototype methodology is called Polyscopic Modeling. What we call polyscopy is this methodology plus the practice that grows on it. When we don't bother to make this distinction, we simply refer to the methodology as polyscopy.

The purpose of the methodology is to spell out the rules. The Polyscopic Modeling definition consists of eight postulates or conventions, of which the first four are principles, and the other four criteria. The principles are a statement of the assumptions based on which we create knowledge and communicate. The criteria serve the purpose of directing the pursuit of knowledge, by saying what information or knowledge should be like, what qualities and effects they need to have. The methods, information formats and applications are not part of the methodology definition. They are allowed to evolve freely.

Generalizing science

Liberating the way we look at the world

The centrally important notion in polyscopy is the scope – which is by definition anything that determines how we look at the world and what we see. This then includes first of all our concepts and methods.

The Polyscopy ideogram stands for the fact that at the point where we've decided to consider our scopes as our own creation, then it becomes natural to adapt them to the purpose of seeing what we need to see – and of seeing the big picture in particular.

A concise justification

This is how Einstein stated his "epistemological credo" on the introductory pages of his Autobiographical Notes. Already the fact that a scientist should begin his personal account of the development of modern physics by stating an "epistemological credo" is significant. Isn't it quite exactly what we've just done above, by turning our epistemology into a convention. And doesn't it also suggest that we can no longer take our epistemological assumptions for granted, that we must spell them out explicitly?I shall not hesitate to state here in a few sentences my epistemological credo. I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. (…) The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. (…) All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for this inquiry in the first place.

You'll notice that there is no reality in this "epistemological credo". There is only "the totality of sense experiences" on the one side, and "the system of concepts" and "syntax" or method on the other. This latter part, posits Einstein, is "freely chosen", and even "the concept of causality" – which was the point of departure of traditional science (whose goal was, indeed, to explain how the observed phenomena follow as a consequence of the inner workings of nature) is freely chosen.

Polyscopy offers provisions for creating concepts and methods by convention, as we have seen. We can define concepts by convention, and also ways how they may be related – which, you'll recall, we called patterns. Both are part of our ways of looking at experience, or scopes.

The "aha experience" – that the things are related in experience as suggested by the provided scope to a sufficient degree – is then also considered as just an experience, which can be communicated from an author to a reader.

The "aha experiences" are essential. They provide us the sense of meaning and orientation. They are especially valuable when they are shared – because they can then orient our collective action. But they can also be dangerous, because we can hold onto them as "reality" and remain closed to further creative exploration and communication. Polyscopy emphasizes that there are multiple ways of looking and multiple ways to make sense. "Truth" in polyscopy (we tend to avoid this word) is a matter of an inner and social dialog – where a fine balance between understanding and staying open is maintained.

Since scopes are human-made by convention, they can be as precise and rigorous as we desire – on any level of generality. Simplicity, indeed, is in the eyes of the beholder (it is a result of the scope). <p>From this foundation a social process follows, which is a fine interplay of the complexity of phenomena and systems on the one side, and the simplicity of our models on the other.

General-purpose science

What results is a general-purpose method which – like a portable flashlight – can be pointed at any phenomenon or issue

The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it brings solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

René Descartes is often "credited" as the philosophical father of the limiting (reductionistic) aspects of science. This Rule 1 from his manuscript "Rules for the Direction of the Mind" (unfinished during his lifetime and published posthumously) shows that also Descartes might have preferred to be remembered as a supporter of polyscopy.

Growing knowledge upward

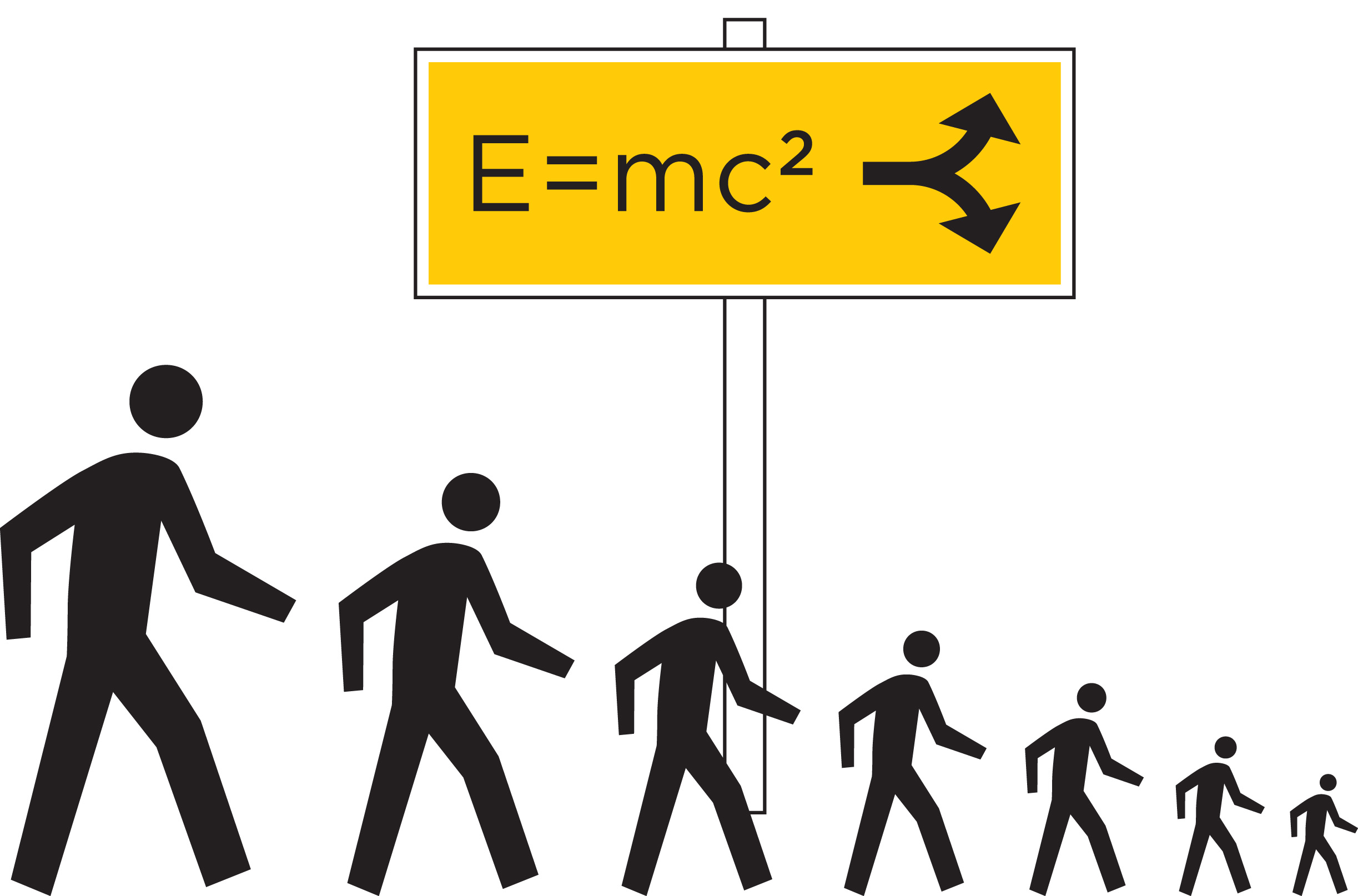

Science on a crossroads

The Science on a Crossroads ideogram points to the possibility to reverse the narrow and technical focus in the sciences – and create general insights and principles about any theme that matters. In the explanation of this ideogram we outline a method by which this can be achieved.

The Science on a Crossroads ideogram depicts the point in the evolution of science when it was understood that the Newton's concepts and "laws" were not parts of the nature's inner machinery, which Newton discovered – but his own creation, and an approximation. Two directions of growth opened up to science – downward, and upward. The sequence of scientists "converging to zero" in the ideogram suggests that only the "downward" option was followed.

The moment when this happened

It has turned out that the very moment when science reached those crossroads has been recorded!

In his "Autobiographical Notes", Einstein describes how the successes of science that resulted from Newton's classical results led to a wide-spread belief that there wasn't really much more than that:

In the beginning (if there was such a thing), God created Newton's laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces. This is all; everything beyond this follows from the development of appropriate mathematical methods by means of deduction.

He then discusses on a couple of pages the anomalies, results of experiments and observed phenomena that were not amenable to such explanation, and concludes:

Enough of this. Newton, forgive me; you found just about the only way possible in your age for a man of highest reasoning and creative power. The concepts that you created are even today still guiding our thinking in physics, although we now know that they will have to be replaced by others further removed from the sphere of immediate experience, if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships.

Why the direction "up" was ignored

The direction "up" is a natural direction for the growth of anything – and of knowledge in particular. Hans't the insight, the wisdom, the general principle, always been the very hallmark of knowledge? So why did science continue its growth only downward – toward more technical, more precise – and more obscure results?

The reason is obvious, and it is also suggested by Einstein: It had to be done, "if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships" – that is, of natural phenomena. They turned out to be far more complex than it was originally believed.

The creation of knowledge had already taken shape, in terms of certain professions. Einstein was of course "a physicist" – and the job of a physicist was to study the physical phenomena, in terms of the masses, velocities etc.

The job of updating the whole production of knowledge – and the job of creating high-level insights – just happened to be in nobody's job description. And hence they remained undone.

By giving those two lines of work a name, knowledge federation, we undertake to call them into existence.

Knowledge federation in pictures

Information

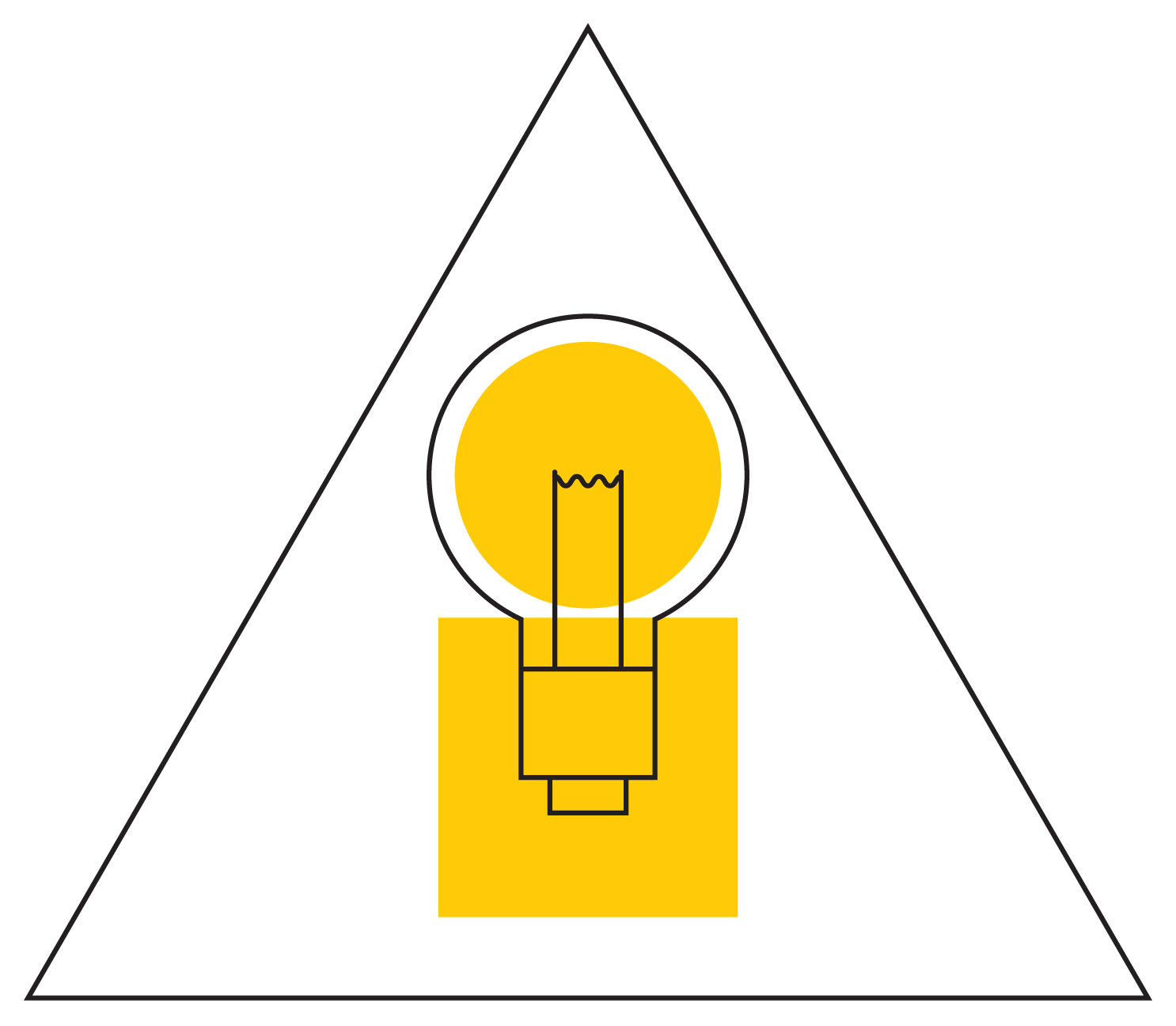

The Information ideogram points to the structure of the information that knowledge federation aims to produce. Or metaphorically, our theme here is the construction of a suitable 'light bulb', and the nature its 'light'. In the explanation of this ideogram it is shown how the methodological ideas just described support this construction. Or more to the point, and metaphorically – this ideogram shows how to create information that is structured (or 'three-dimensional'), not 'flat'.

The “i” in this image (which stands for "information") is composed of a circle on top of a square. The square stands for the technical and detailed low-level information. The square also stands for examining a theme or an issue from all sides. The circle stands for the general and immediately accessible high-level information. This ideogram posits that information must have both. And in particular that without the former, without the 'dot on the i', the information is incomplete and ultimately pointless.

This ideogram also suggests how to create high-level views based on low-level ones. And to justify high-level claims based on low-level ones – by 'rounding off' or 'cutting corners'.

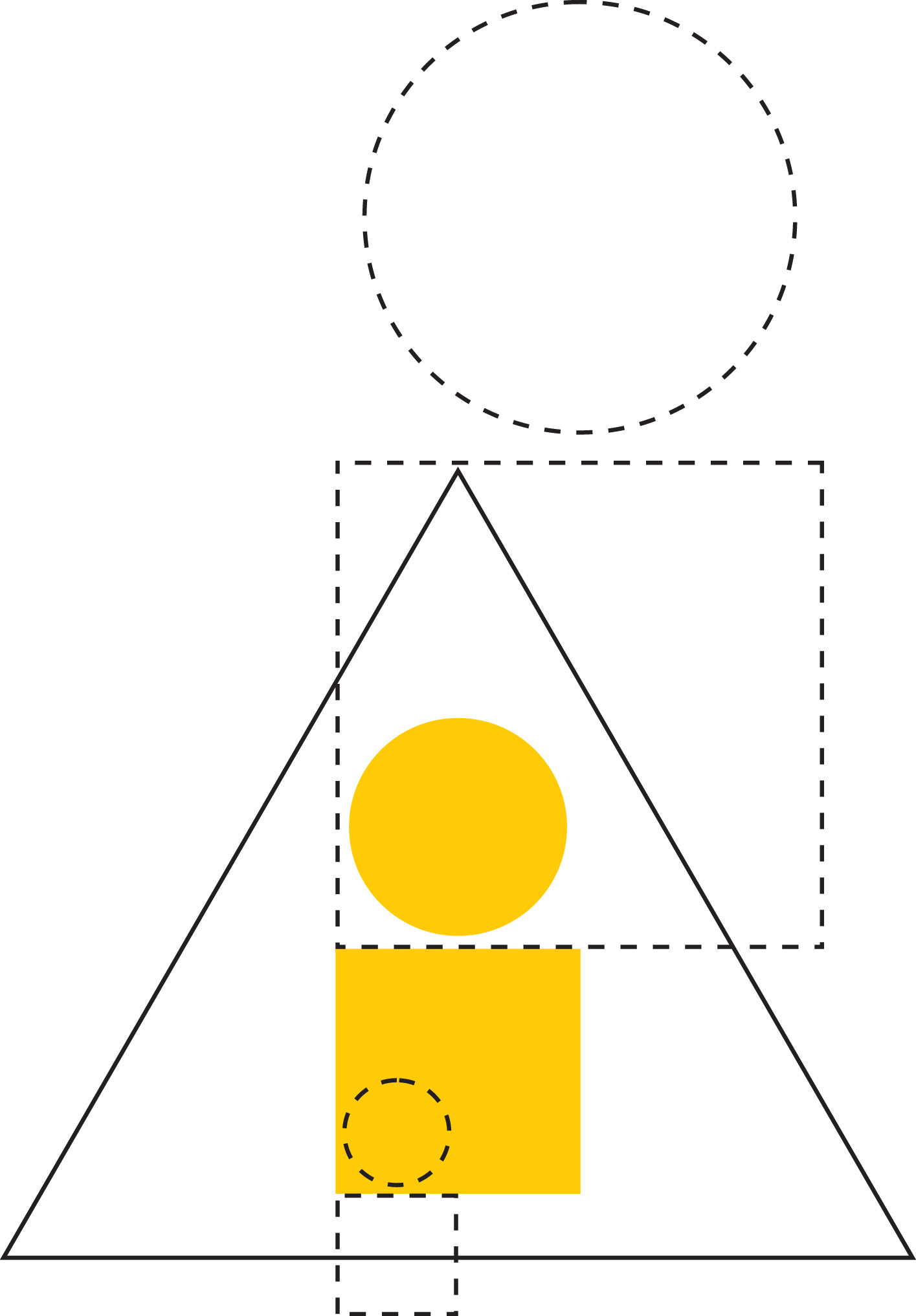

Knowledge

The Knowledge ideogram depicts knowledge federation as a process – and also the kind of knowledge that this process aims to produce.

It follows from the fundamentals we've just outlined that (when our goal is to inform the people) knowledge federation will do its best to federate knowledge according to relevance – and adapt its choice of scope to that task. The rationale is that "the best available" knowledge will generally be better than no knowledge at all. Knowledge, and information, are envisioned to exist as a holarchy – where the low-level "pieces of information" or holons serve as side views for creating high-level insights. Multiple and even contradictory views on any theme are allowed to co-exist. A core function of federation as a process is to continuously negotiate and re-evaluate the relevance and the credibility of those views.

Examples

Convenience paradox

Redirecting our "pursuit of happiness" is of course a natural way to give a new direction to our 'bus'. It is also a natural application where these ideas can be put to test.

The Convenience Paradox ideogram depicts a situation where the pursuit of a more convenient direction (down) leads to an increasingly less convenient condition. The human figure in the ideogram is deciding which way to go. He wants his way (of life) to be more easy and pleasant, or more convenient. If he follows the direction that seems more convenient, he will end up in a less convenient condition – and vice versa.

By representing the way to happiness as yin (which stands for dark, or obscure) in the traditional yin-yang ideogram, it is suggested that the way to convenience or happiness must be illuminated by suitable information.

This ideogram is of course only the high-level part, the circle, or the 'dot on the i'. Its low-level part or justification consists of a variety of insights from a diverse range of fields (which brings together experiences from physiotherapy traditions such as Feldenkrais and Alexander, modern psychoanalysis, Buddhism and other similar traditions...) to establish the convenience paradox as a pattern. The high-level part brings the low-level views together and gives them relevance (they provide us exactly the information we need to be able to truly improve our condition).

This example shows how insights from a variety of eras and traditions may be revitalized and combined together, to inform our contemporary pursuit of happiness

Power structure

Another strong pursuit that gives direction to our societal and cultural evolution is our pursuit of justice. But who is the enemy?

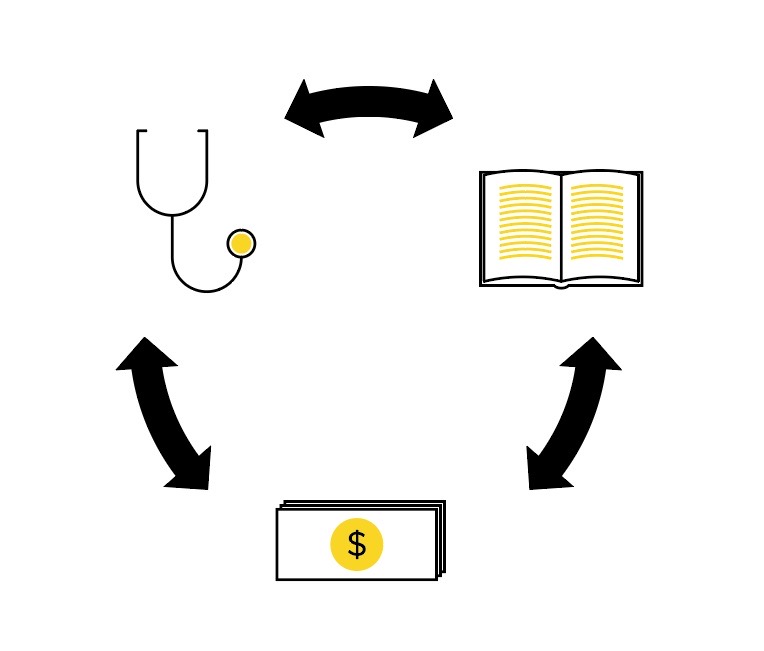

The Power Structure ideogram depicts the power structure as a new or a designed way to conceive of the traditional notions "power holder" and "political enemy". The power structure is a structure which combines power interests (represented by the dollar sign), our values and ideas (represented by the book) and our condition of wellbeing (represented by the stethoscope). A point of the ideogram is that those visible entities evolve together and depend on one another – but this dependence is subtle, and needs to be illuminated by suitable information.

The justification combines insights from a spectrum of areas ranging from sociology (for ex. the works of Bauman and Bourdieu) to artificial intelligence and combinatorial optimization.

Two key insights result: That "the enemy is us"... and that our social-systemic evolution, when abandoned to "the survival of the fittest", tends to result in growing and strengthening power structures...