Difference between revisions of "IMAGES"

m |

m |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<div class="col-md-3"><h2>Rebuilding knowledge work</h2></div> | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>Rebuilding knowledge work</h2></div> | ||

<div class="col-md-7"><h3>The issue of epistemology</h3> | <div class="col-md-7"><h3>The issue of epistemology</h3> | ||

| − | <p>Our ideas about what constitutes good knowledge have evolved since antiquity, and now find their foremost expression in science. Science has also become, through an evolutionary process, our trusted source of knowledge. What we'll be talking about here is the possibility of continuing this evolution a step further, and in a new direction | + | <p>Our ideas about what constitutes good knowledge have evolved since antiquity, and now find their foremost expression in science. Science has also become, through an evolutionary process, our trusted source of knowledge. What we'll be talking about here is the possibility of continuing this evolution a step further, and in a new direction, where (what we've learned from) science is adapted to what is now a vital task – of giving contemporary people and society the kind of information they need.</p> |

<p> During the past century fundamental insights have been reached in science and philosophy that now enable us to develop knowledge work on entirely new premises. And to <em>repurpose</em> knowledge and knowledge work on this new basis, by adapting them to their increasingly vital social role – the role of informing people. We shall summarize those insights briefly in our very first story in Federation through Stories. Here, however, we shall represent them largely by the insights of a single scientist – Albert Einstein. Already a handful of brief excerpts from his texts will turn out to be sufficient for our purpose. Einstein here appears in his usual role of an icon, representing "modern science".</p> | <p> During the past century fundamental insights have been reached in science and philosophy that now enable us to develop knowledge work on entirely new premises. And to <em>repurpose</em> knowledge and knowledge work on this new basis, by adapting them to their increasingly vital social role – the role of informing people. We shall summarize those insights briefly in our very first story in Federation through Stories. Here, however, we shall represent them largely by the insights of a single scientist – Albert Einstein. Already a handful of brief excerpts from his texts will turn out to be sufficient for our purpose. Einstein here appears in his usual role of an icon, representing "modern science".</p> | ||

<h3>Blueprint of a socio-technical lightbulb</h3> | <h3>Blueprint of a socio-technical lightbulb</h3> | ||

Revision as of 14:51, 31 October 2018

Contents

Federation through Images

Rebuilding knowledge work

The issue of epistemology

Our ideas about what constitutes good knowledge have evolved since antiquity, and now find their foremost expression in science. Science has also become, through an evolutionary process, our trusted source of knowledge. What we'll be talking about here is the possibility of continuing this evolution a step further, and in a new direction, where (what we've learned from) science is adapted to what is now a vital task – of giving contemporary people and society the kind of information they need.

During the past century fundamental insights have been reached in science and philosophy that now enable us to develop knowledge work on entirely new premises. And to repurpose knowledge and knowledge work on this new basis, by adapting them to their increasingly vital social role – the role of informing people. We shall summarize those insights briefly in our very first story in Federation through Stories. Here, however, we shall represent them largely by the insights of a single scientist – Albert Einstein. Already a handful of brief excerpts from his texts will turn out to be sufficient for our purpose. Einstein here appears in his usual role of an icon, representing "modern science".

Blueprint of a socio-technical lightbulb

If the word "epistemology" does not mean much to you, consider what is being told here as simply a description of a new principle of operation for the socio-technical lightbulb. That fire can provide us light, that we've known since before the civilization. But now we'll see that, metaphorically speaking, electricity can provide us an even much stronger light, which we can point at will to illuminate whatever needs to be seen. What will be described is both what 'electricity' here means, and how a lightbulb with suitable properties may be constructed.

Steps toward big picture science

We'll show how the characteristic approach to knowledge that has been developed in the sciences can be generalized and made applicable to any theme or issue. And most importantly, we shall see how this approach can be adapted to the need of creating big-picture information, and provide insight and orientation.

We shall at the same time use some elements of this big-picture science, notably the ideogram. As we have seen, the ideogram play in this generalization of science a similar role as mathematical formulas do in physics – they provide a general message about how the things are related, that can be recognized at a glance. An important use of ideograms here is to provide a gestalt – an insight into a nature of situation, which points to a way in which the situation may need to be handled.

Repurposing science

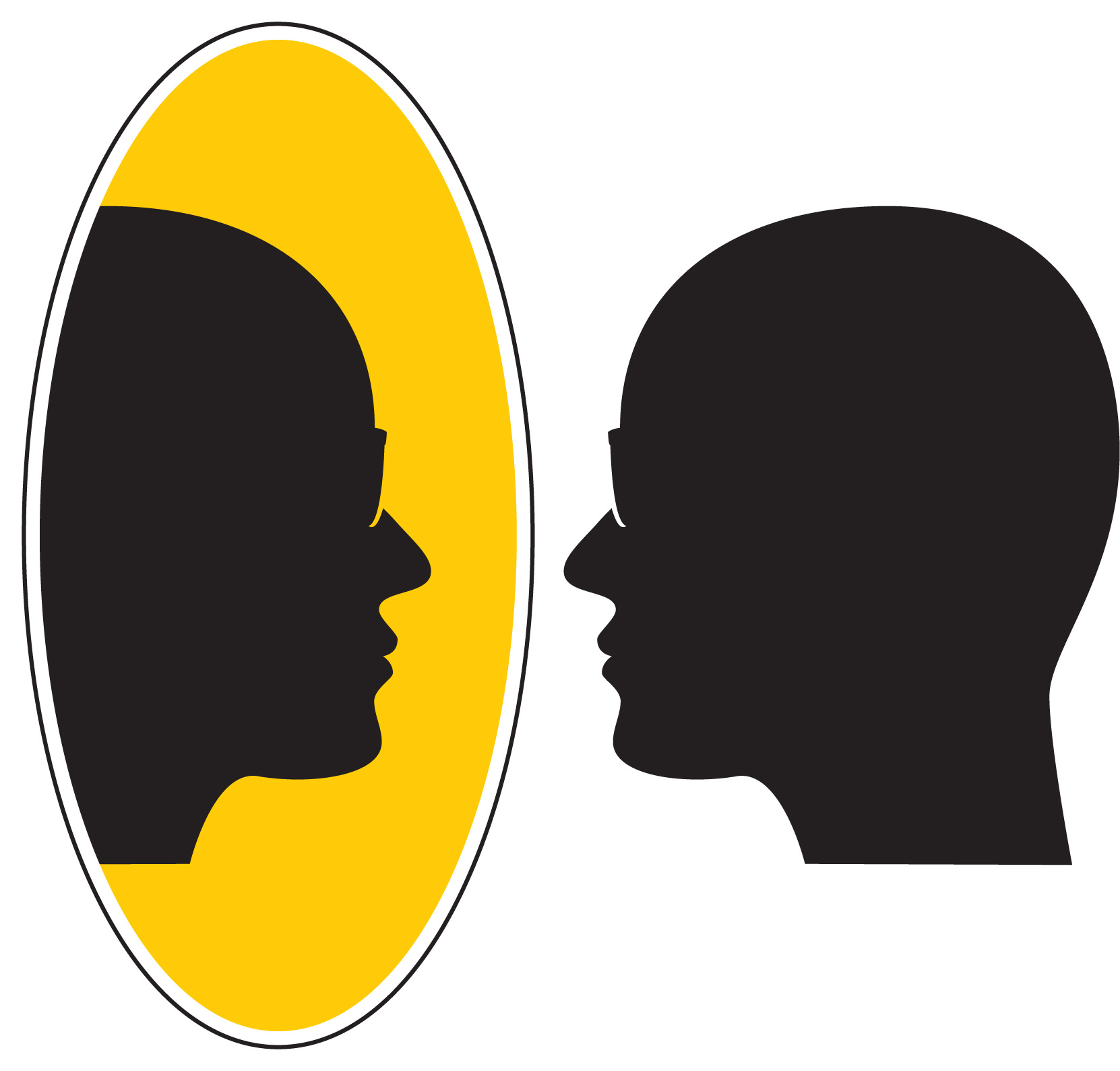

The academic mirror

On every university campus there is a mirror. Busy with article deadlines and courses, we do not normally see it. But it is there! When we see ourselves in this mirror, we see the same world that we see around us. But we also see ourselves in the world.

The mirror here represents the insight, reached in so many ways in 20th century's science and philosophy (see Federation through Stories), that we cannot really build our knowledge work solidly on the age-old assumption that the purpose of knowledge is to mirror reality "objectively", as it truly is.

When we see ourselves in this mirror, we see that it is really us that have created both our knowledge and our knowledge work. We realize that we are not disembodied spirits hovering over the world and looking at it objectively – but people living in the world, and responsible for it.

As the case is in Louis Carroll's familiar story, this academic mirror too can be walked right through! And when we do that, we find ourselves in an entirely different academic reality. (You may now understand Knowledge federation as a model or prototype of that reality.)

We cannot really know reality

Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world. In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison.This often quoted excerpt from Einstein and Infeld's Evolution of Physics will suggest to us that all we are really doing – and can do – is making models. And that it would be hard to even imagine a procedure by which we could confirm that our models correspond to the real thing.

This second excerpt, from Einstein's comments on Bertrand Russell's Theory of Knowledge, will suggest that our common belief that our representations correspond to reality has largely been based on illusions.During philosophy’s childhood it was rather generally believed that it is possible to find everything which can be known by means of mere reflection. (...) Someone, indeed, might even raise the question whether, without something of this illusion, anything really great can be achieved in the realm of philosophical thought – but we do not wish to ask this question. This more aristocratic illusion concerning the unlimited penetrative power of thought has as its counterpart the more plebeian illusion of naïve realism, according to which things “are” as they are perceived by us through our senses. This illusion dominates the daily life of men and animals; it is also the point of departure in all the sciences, especially of the natural sciences.

But if our goal is is to distinguish truth from illusion – how can we rely on a criterion that is impossible to verify? And whose positive indications themselves tend to be results of illusion?

A new foundation for knowledge

We emphasize that the new foundation we are proposing does not depend on what's just been said. Even if depicting reality in an objective way were possible; and even if science really did that – even then this way of founding knowledge would be rigorous.

The reason is that this new foundation is independent of the very notion of reality. It simply circumvents it altogether.

This is done by resorting to what Villard Van Orman Quine called truth by convention. It's the kind of truth that is common in mathematics: "Let x be... Then..." It is meaningless to ask whether x "really is" as stated. In "Truth by Convention", Quine posits that

So why not allow knowledge work at large to progress in that same manner?The less a science has advanced, the more its terminology tends to rest on an uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. With increase of rigor this basis is replaced piecemeal by the introduction of definitions. The interrelationships recruited for these definitions gain the status of analytic principles; what was once regarded as a theory about the world becomes reconstrued as a convention of language. Thus it is that some flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science.

What makes 'the magic' possible, of 'walking through the mirror', is that the truth on the other side is (by convention) the truth by convention. We call this basic convention the methodology.

By creating a methodology, the age-old preoccupation with truth and reality is established on the academic terrain that Herbert Simon called "the sciences of the artificial" – which is of course just a technical term for our metaphorical reality on the other side of the mirror.

The sciences of the artificial, according to Simon, do not study what objectively exists in the natural world – but man-made things, with the goal of adapting them to the purposes they serve in the human world.

Spelling out the rules

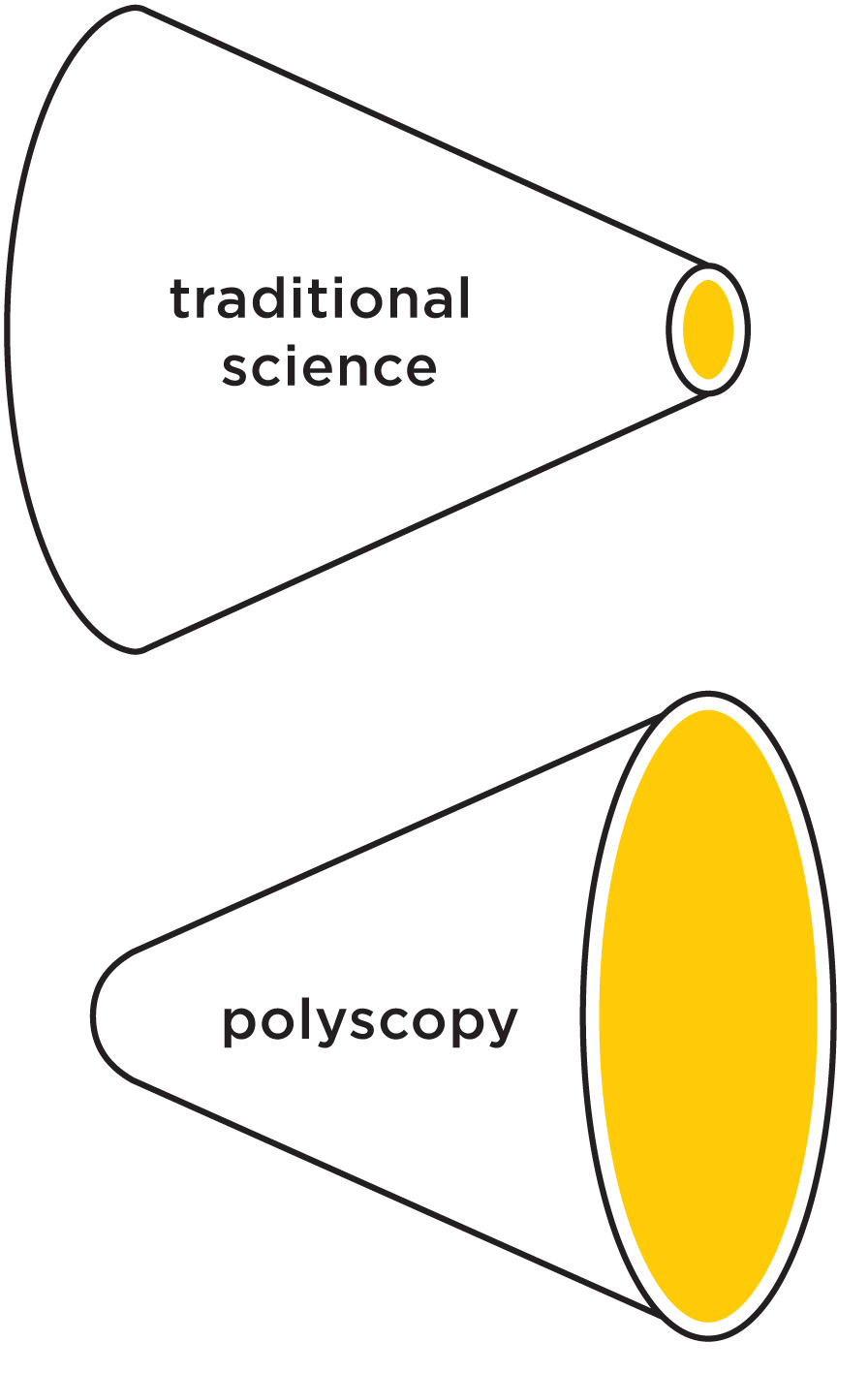

The prototype methodology is called Polyscopic Modeling. What we call polyscopy is this methodology plus the practice that grows on it. When we don't bother to make this distinction, we simply refer to the methodology as polyscopy.

The purpose of the methodology is to spell out the rules. The Polyscopic Modeling definition consists of eight postulates or conventions, of which the first four are principles, and the other four criteria. The principles are a statement of the assumptions based on which we create knowledge and communicate. The criteria serve the purpose of directing the pursuit of knowledge, by saying what information or knowledge should be like, what qualities and effects they need to have. The methods, information formats and applications are not part of the methodology definition. They are allowed to evolve freely.

Generalizing science

Liberating the way we look at the world

The centrally important notion in polyscopy is the scope – which is by definition anything that determines how we look at the world and what we see. This then includes first of all our concepts and methods.

The Polyscopy ideogram stands for the fact that at the point where we've decided to consider our scopes as our own creation, then it becomes natural to adapt them to the purpose of seeing what we need to see – and of seeing the big picture in particular.

A concise justification

This is how Einstein stated his "epistemological credo" on the introductory pages of his Autobiographical Notes. Already the fact that a scientist should begin his personal account of the development of modern physics by stating an "epistemological credo" is significant. Isn't it quite exactly what we've just done above, by turning our epistemology into a convention. And doesn't it also suggest that we can no longer take our epistemological assumptions for granted, that we must spell them out explicitly?I shall not hesitate to state here in a few sentences my epistemological credo. I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. (…) The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. (…) All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for this inquiry in the first place.

You'll notice that there is no reality in this "epistemological credo". There is only "the totality of sense experiences" on one side, and "the system of concepts" and "syntax" or method on the other. This latter part, posits Einstein, is "freely chosen", and even "the concept of causality" – which was the point of departure of traditional science (whose goal was, indeed, to explain how the observed phenomena follow as a consequence of the inner workings of nature) is freely chosen.

Polyscopy offers provisions for creating concepts and methods by convention, as we have seen. We can define concepts by convention, and also ways how they may be related – which, you'll recall, we called patterns. Both are part of our ways of looking at experience, or scopes.

The "aha experience" – that the things are related in experience as suggested by the provided scope to a sufficient degree – is then also considered as just an experience, which can be communicated from an author to a reader.

The "aha experiences" are essential. They provide us the sense of meaning and orientation. They are especially valuable when they are shared – because they can then orient our collective action. But they can also be dangerous, because we can hold onto them as "reality" and remain closed to further creative exploration and communication. Polyscopy emphasizes that there are multiple ways of looking and multiple ways to make sense. "Truth" in polyscopy (we tend to avoid this word) is a matter of an inner and social dialog – where a fine balance between understanding and staying open is maintained.

Since scopes are human-made by convention, they can be as precise and rigorous as we desire – on any level of generality. Simplicity, indeed, is in the eyes of the beholder (it is a result of the scope). <p>From this foundation a social process follows, which is a fine interplay of the complexity of phenomena and systems on the one side, and the simplicity of our models on the other.

General-purpose science

What results is a general-purpose method which – like a portable flashlight – can be pointed at any phenomenon or issue

The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it brings solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

René Descartes is often "credited" as the philosophical father of the limiting (reductionistic) aspects of science. This Rule 1 from his manuscript "Rules for the Direction of the Mind" (unfinished during his lifetime and published posthumously) shows that also Descartes might have preferred to be remembered as a supporter of polyscopy.