Holotopia: Socialized reality

Contents

- 1 H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

- 2 Socialized reality

- 2.1 Let us federate our culture's foundations

- 2.2 Stories

- 2.3 "Reality" is a myth

- 2.4 Causal comprehension is not a reality test

- 2.5 "Reality" is constructed

- 2.6 "Reality" is a product of socialization

- 2.7 "Reality" is a basic human need

- 2.8 Socialization determines our awareness

- 2.9 Socialization is a prerogative of power structure

- 2.10 Our culture is created by power structure

- 2.11 Socialized reality in popular culture

H O L O T O P I A: F I V E I N S I G H T S

Socialized reality

Let us federate our culture's foundations

From the traditional culture we inherited a myth incomparably more subversive than the myth of creation. That myth now serves as the foundation stone on which the edifice of our culture has been erected.

That error is, however, easily forgiven, if we take into account that the idea that "truth" means "correspondence with reality" is coded not only in our common sense, but also in our very language. When I write "worldviews", my word processor underlines it in red. The word "worldview" doesn't have a plural form; since there is only one world, there can be only one worldview—the one that corresponds to that world.

Our situation, however, is calling for that we revisit and reconfigure that very foundation stone on which the edifice of our culture has been constructed.

Before we begin, let us emphasize once again that our goal is not to critique our present foundations; or even to propose new and better ones. Our goal is both more humble and more ambitious than that—namely to initiate and develop a social process through which the assessment and improvement of our culture's foundations will be kept in sync with our knowledge of knowledge, and with our society's needs.

Stories

"Reality" is a myth

The common belief that "truth" means "correspondence to reality", and that our ideas, when they are "true", correspond to reality, has been shown to be (1) impossible to verify and (2) a common product of illusion (see our story argument here).

Why base our creation of truth and meaning, and our pursuit of knowledge—which are all-important human activities—on a criterion that cannot be verified; and which itself tends to be a product of illusion?

Causal comprehension is not a reality test

It takes only a moment of reflection to see just how much the "aha feeling"—when we understand how something may result as a consequence of known causes—has been elevated to the status of the reality test. But is it really that?

The Enlightenment empowered the human reason to comprehend the world. Science taught us that women cannot fly on brooms—because that would violate some well established "natural laws". Innumerable prejudices and superstitions were dispelled.

But we've also thrown out the baby with the bathwater!

Reason cannot know "reality"

Even our common sense is a product of (our and our culture's) experience, with things such as pebbles and waves of water. We have no reason to believe that it will still work when applied to things we do not have in experience, such as small quanta of matter—and it doesn't!. A complete argument, based on the double-slit experiment, is in Oppenheimer's essay "Uncommon Sense".

"Reality" has no a priori structure

Indeed, when the insights reached in the last century's science and philosophy are taken into account, the reason is compelled to conclude that there is no "the reality" out there, waiting to be discovered. All we have to work with is human experience—of a world that, to our best knowledge, has no a priori structure.

A piece of material evidence is Einstein's "epistemological credo", which we commented here.

"Reality" is constructed

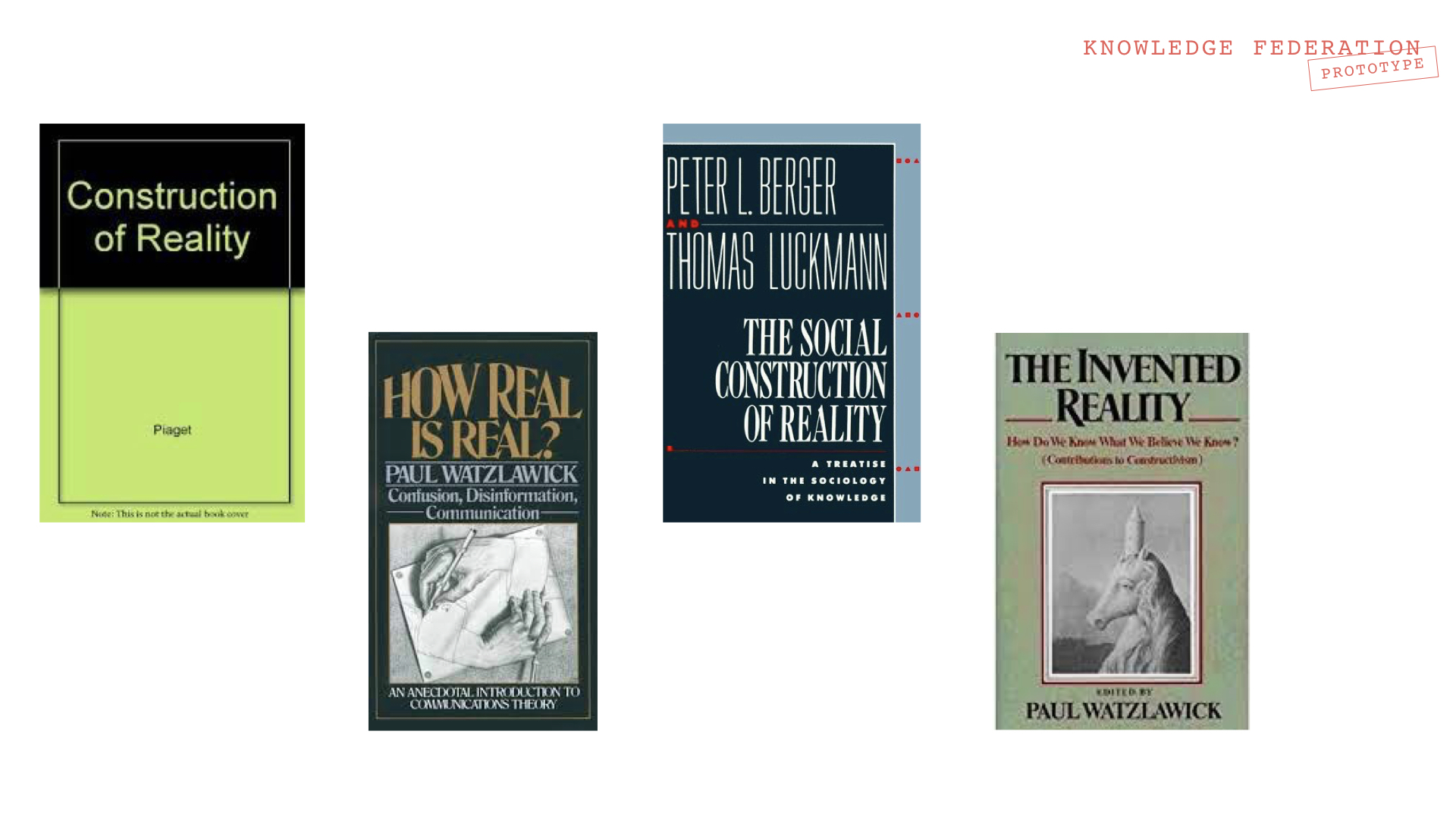

Having thus lost its bearings in philosophy, "reality" as preoccupation migrated to biology, psychology and sociology—where the mechanisms of our reality constructions could be studied.

We represented them by Maturana, Piaget and Berger and Luckmann—see our commentary that begins here.

"Reality" is a product of socialization

Bourdieu's "theory of practice"

We have now come to the first of the three main components of the socialized reality insight—that what we consider "reality" is really a product of socialization. But what exactly does this mean? What is socialization?

While a wealth of academic insights may be drawn upon to illuminate this uniquely relevant idea, we here represent them all by the work of a single researcher, sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. His "theory of practice" is the theory of socialization.

Specifically, the meaning of Bourdieu's keyword doxa (which he adopted from Max Weber, and whose usage dates all the way back to Plato) points to an essential property of what we call socialized reality. Bourdieu used this keyword to point to the common experience that people had through the ages—that the societal order of things in which they lived was the only possible one. "Orthodoxy" implies that more than one are possible, but that only one ("ours") is the "right" one. Doxa ignores even the possibility of alternative options.

Two other Bourdieu's central keywords, "habitus", and "field", will provide us what we need to take along. Think of "habitus" as embodied predispositions to act and behave in a certain way. Think of "field" as something akin to a magnetic field, which deftly draws each person in a society to his or her "habitus". Instead of theorizing more, we provide an intuitive explanation in terms of a common situation, which is intended to serve as a parable.

What makes a real king real

The king enters the room and everyone bows. Naturally, you bow too. Even if you may not feel like doing that, deep inside you know that if you don't bow down your head, you may lose it.

So what is it, really, that makes the difference between "a real king", and an imposter who "only believes" that he's a king? Both consider themselves as kings, and impersonate the corresponding "habitus". In the former case, however, everyone else has also been successfully socialized accordingly.

A "real king" will be treated with highest honors. An imposter will be incarcerated in an appropriate institution. Despite the fact that all too often, a single "real king" caused far more suffering and destruction than all the madmen and criminals combined.

"Reality" is a basic human need

Aaron Antonovsky and salutogenesis

Among the women who survived the Holocaust, about two thirds later developed a variety of psychosomatic problems. Aaron Antonovsky focused his research on the ones that didn't. He found out that what distinguished them was their greater "sense of coherence"—which he defined as "feeling of confidence that one's environment is predictable and that things will work out as well as can reasonably be expected". Today Antonovsky is considered an iconic progenitor of "salutogenesis"—the scientific study of conditions for and ways to health.

We mention Antonovsky to point to what is perhaps intuitively obvious: That a shared "reality" is a basic human need. Every social group provided its members with a shared "sense of coherence" (a predictable environment, a relatively stable role and "habitus" recognized by others, a shared way to comprehend the world...) But at what price!

Socialization determines our awareness

Antonio Damasio and Descartes' error

The second main component of the socialized reality insight represents a major turning point from the self-image which the Enlightenment gave us, humans; and which served as the foundation for our democracy, legislature, ethics, culture... Here too we represent a large body of research with the work of a single researcher—Antonio Damasio.

The point here—which Damasio deftly coded into the very title of his book "Descartes' Error"—is that we are not the rational decision makers, as the founding fathers of the Enlightenment made us believe. Damasio showed that the very contents of our rational mind (our priorities, and what options we are at all capable to conceive of and consider) are controlled by a cognitive filter, which is pre-rational and embodied.

Damasio's theory synergizes beautifully with Bourdieu's "theory of practice", to which it gives a physiological explanation.

George Lakoff and philosophy in the flesh

Lakoff, a cognitive linguist, and Johnson, a philosopher, teamed up to give us a revision of philosophy, based on what the cognitive science found, under the title "philosophy in the flesh". The book's opening paragraphs, titled "How Cognitive Science Reopens Central Philosophical Questions", read:

The mind is inherently embodied.

Thought is mostly unconscious.

Abstract concepts are largely metaphorical.

These are three major findings of cognitive science. More than two millennia of a priori philosophical speculation about these aspects of reason are over. Because of these discoveries, philosophy can never be the same again.

When taken together and considered in detail, these three findings from the science of the mind are inconsistent with central parts of Western philosophy. They require a thorough rethinking of the most popular current approaches, namely, Anglo-American analytic philosophy and postmodernist philosophy.

Socialization is a prerogative of power structure

Bourdieu and symbolic power

The third and last main component of the socialized reality insight is that the power structure largely draws its power from socialized reality. This insight thoroughly changes our understanding of power; and what it would take to be truly free.

We elaborated on these ideas here.

While looking up "prerogative" in Webster's dictionary, we found the following example of the relationship between power structure and "habitus": "in his youth, to sit thus was the prerogative of the gentry — Oscar Handlin".

Pavlov and Chakhotin

Ivan Pavlov got a Nobel Prize for his research on socializing dogs.

After having worked with Pavlov in his laboratory, Sergey Chakhotin participated in the 1932 German elections against Hitler. He noticed that Hitler was socializing German people to accept his ideas; and claimed that to counter them, similar means would have to be used.

Later, in France, Chakhotin explained his insights about socializing people in a book titled "Viole des foules par la propagande politique"—see it commented here.

Pavlov – Chakhotin

Pavlov's experiments on dogs (for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize) can serve as a parable for socialization

After working with Pavlov in his laboratory, Chakhotin participated in 1932 German elections against Hitler. Understood that Hitler was conditioning or socializing the German people. Wrote "Le viole des foules..." (see the comments, link TBA).

Chakhotin practiced, and advocated, to use non-factual or implicit information to counteract the socialization attempts by political bad guys (see the image on the right). Adding "t" to the familiar Nazi greeting produced "Heilt Hitler" (cure Hitler).

Edelman and symbolic action

Already in the 1960s the researchers knew that the conventional mechanisms of democracy (the elections) don't serve the purpose they were assumed to serve (distribution of power)—because (field research showed) the voters are unfamiliar with the candidates' proposed policies, the incumbents don't tend to fulfill their electoral promises and so on. Edelman contributed an interesting addition: It's not that the elections don't serve a purpose; it's just that this purpose is different from what's believed. The purpose is symbolic (they serve to legitimize the governments and the policies, by making people feel they were asked etc.)

Edelman, as a political science researcher, contributed a quite thorough study of the "symbolic uses of politics".

Our culture is created by power structure

It is enough to look around. But here's an interesting story about how this sad state of affairs developed.

Freud and Bernays

While Sigmund Freud was struggling to convince the European academics that we, humans, are not as rational as they liked to believe, his American nephew Edward Bernays had no difficulty convincing the American business that exploiting this characteristics of the human psyche is—good business. Today, Bernays is considered "the founder of public relations in the US", and of modern advertising. His ideas "have become standard in politics and commerce".

The four documentaries about Bernays' work and influence by Adam Curtis (click here) are most highly recommended.

Visual literacy

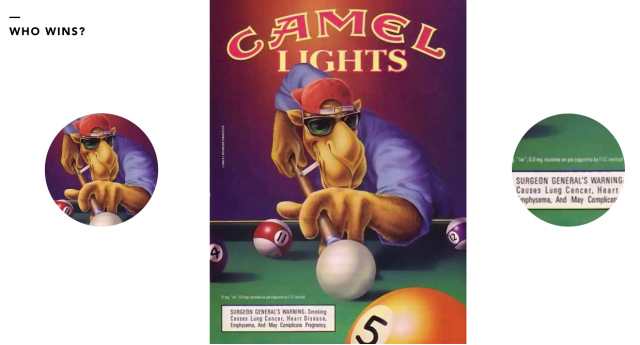

In 1969, four visionary researchers saw the need, and initiated the International Visual Literacy Association. What exactly did they see? We introduce their ideas by the following ideogram, see it commented here.

In the above picture the implicit information meets the explicit information in a direct duel. Who wins? Since this poster is a cigarette advertising, the answer is obvious.

And so is this conclusion:

While our "official culture" is focused on explicit messages and rational discourse, our culture is being dominated, and created, by implicit information—the imagery we have not yet learned to rationally decode, and counteract.

Socialized reality in popular culture

As always, this core element present in our 'collective unconscious' (even if it has all too often eluded our personal awareness) has found various expressions in popular culture—as the following two examples will illustrate.

The Matrix

The Matrix is an obvious metaphor for socialized reality—where the "machines" (read power structures) are keeping people in a media-induced false reality, while using them as the power source. The following excerpt require no comments.

Morpheus: The Matrix is everywhere. It is all around us. Even now, in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window or when you turn on your television. You can feel it when you go to work... when you go to church... when you pay your taxes. It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Morpheus: That you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else you were born into bondage. Into a prison that you cannot taste or see or touch. A prison for your mind.

Oedipus Rex

XXXXXXX </div> </div>