Difference between revisions of "Holotopia/T"

(Created page with " <!-- AAA <div class="row"> <div class="col-md-3"><h2>We foster a <em>meme</em></h2></div> <div class="col-md-7"> <p>Margaret Mead also left us an admonition—what exactly...") |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-3"><h2>We foster a <em>meme</em></h2></div> | <div class="col-md-3"><h2>We foster a <em>meme</em></h2></div> | ||

Revision as of 12:52, 23 September 2020

We foster a meme

Margaret Mead also left us an admonition—what exactly distinguishes "a small group of citizens" that is capable of making a large difference—which we do not take lightly.

"(W)e take the position that the unit of cultural evolution is neither the single gifted individual nor the society as a whole, but the small group of interacting individuals who, together with the most gifted among them, can take the next step; then we can set about the task of creating the conditions in which the appropriately gifted can actually make a contribution. That is, rather than isolating potential "leaders," we can purposefully produce the conditions we find in history, in which clusters are formed of a small number of extraordinary and ordinary men and women, so related to their period and to one another that they can consciously set about solving the problems they propose for themselves."

We have demonstrated that we are not creating the conditions "in which the appropriately gifted can actually make a contribution". Our stories, deliberately chosen to be a half-century old, show that the "appropriately gifted" have offered their gifts—but we did not receive them.

Through innumerably many 'carrots and sticks', we have been socialized to turn a deaf ear to the hero in us, and conform to our institutions as "little cogs that mesh together" (see this excerpt from the animated film The Incredibles).

To act in ways we know don't work, because our embodied experience tells us that, is an epitome of stupidity. Unless, of course, our goal is to shift the paradigm—in which case acting in ways we know don't work is exactly what we have to be able to do!

Can the Holotopia prototype mobilize enough "human quality", within us who take in it an active part, and on the interface where it meets the world, to manifest its vision?

In the Holotopia prototype, we turn the challenge of transforming the cultural ecology that would make us "little cogs that mesh together" into a co-creative strategy game.

Our core goal is, in other words, to federate a value, and a way of being in the world—where we make both things and ourselves whole—by being responsible, responsive and self-organizing parts in a whole.

Tactical assets

The Holotopia prototype is conceived as a collaborative strategy game—where we make tactical moves toward the holotopia vision. By prime it by this collection of tactical assets.

Art

The Holotopia prototype extends science as we know it—and at the same time thoroughly transforms it. The science we practice is not limited to academic professionals and laboratories, on the contrary—it extends the traditional academia into a vibrant space of transformative action.

An example of a transformative space, created by our "Earth Sharing" pilot project, in Kunsthall 3.14 art gallery in Bergen, Norway.

Just as the case was during the Renaissance, only the art can give transformative insights a transformative form.

We are reminded of Michelangelo painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and in the midst of the old order of things planting seeds of a new one. Art is what first comes to mind when we think of the Renaissance. What sort of art will be the vehicle for this new one?

When Marcel Duchamp exhibited the urinal, he challenged not only the meaning of "art", but also the limits of what we can conceive of as creative action. The deconstruction of the tradition, has, however, now been completed.

Our situation calls for artistic construction of a completely new kind.

Here is a very brief sketch of holotopia ("white") being "(...) also the new red"; through a brief sketch of (possible) holotopia's interpretation of "young Marx". The point is: Young Marx arrived at a theoretical / philosophical standpoint for understanding the society and its ills. But having seen the miserable condition of the workers, he (in the eyes of the revolutionary left "matured" and) eschewed the intellectual idealism of his era, and embraced revolutionary engagement instead. The paradox of Marx is that this latter having become controversial and in many ways inappropriate for our conditions, the former got forgotten and ignored...

In "Production of Space", Henri Lefebvre summarized Marx's essential and increasingly vital point, his objection to capitalism (or what we would call power structure evolution) as causing "alienation" (by which humans are forced to abandon their quest for wholeness), by observing that capital (machines, tools, materials...) or "investments" are products of past work, and hence represent "dead labour". Our past activity "crystalyzed, as it were, and became a precondition for new activity." Under capitalism, "what is dead takes hold of what is alive". Lefebvre proposed to turn this relationship upon its head. "But how could what is alive lay hold of what is dead? The answer is: through the production of space, whereby living labour can produce something that is no longer a thing, nor simply a set of tools, nor simply a commodity.

As an initiative in the arts, Holotopia produces a space where what is alive in us can overcome what is making us dead.

Stories

The "stories" here are what is technically called vignettes. They are a basic journalistic technique (where a relevant or complex issue is made palpable by telling people and situation stories), applied to basic academic ideas and developments. But not only; stories or vignettes can be used to federate any other relevant meme as well.

We are, of course, not limited to verbal story telling. Like the ideograms, the vignettes can take any sort of form, on any sort of medium, or their combination. Hence our collection of stories are offered as a way to federate the core ideas and insights that together compose the holotopia—by making them available to creative media people.

It may seem that story telling is an inefficient way to highlight a point, and hence also unacademic. But exactly the opposite is the case! The vignettes are beautifully efficient, because they point to numerous nuances at once, and the way in which they are connected. Hence they are invaluable for the cause of seeing things whole.

We have seen a number of such stories already. Here, however, we illustrate the concept by focusing on a single one—which is the iconic story introducing the knowledge federation.

The second book in the Holotopia series, tentatively titled "Systemic Innovation", and subtitled "Cybernetics of Democracy", will federate this story.

The incredible history of Doug Engelbart

We've told this story many times, and will federate them properly in the file linked by the title. We here only share the beginning, and a punchline.

It's 1950, and Christmas is drawing near. An idealistic young man, at the beginning of his career, is taking a critical look at what's ahead of him: He is twenty five, with excellent education, employed as an engineer by (what would became) NASA, engaged to be married... He sees his career as a straight path to retirement; and he doesn't like what he sees. A man's life should have a purpose! So right there and then Engelbart makes a decision: He will optimize his career so as to maximize the benefits it would have for the mankind.

After that, just as every good engineer should do, he spent three month intensely pondering about what would be the best way to fulfill his intention. Then he had an epiphany.

We could say "the rest is history"—but the nature of Engelbart's epiphany has not yet been understood. His gift to the world has not ye been received. In spite of being celebrated as the Silicon Valley's greatest inventor, or as we might phrase this, its 'giant in residence'—Engelbart passed away in 2013 feeling he had failed.

When properly told, this story is incredible. What makes it so interesting for us is that in spite of that it can be understood—when we place it as a transformative meme into the context of the five insights. Then, however, the story illustrates a range of phenomena that are central to holotopia.

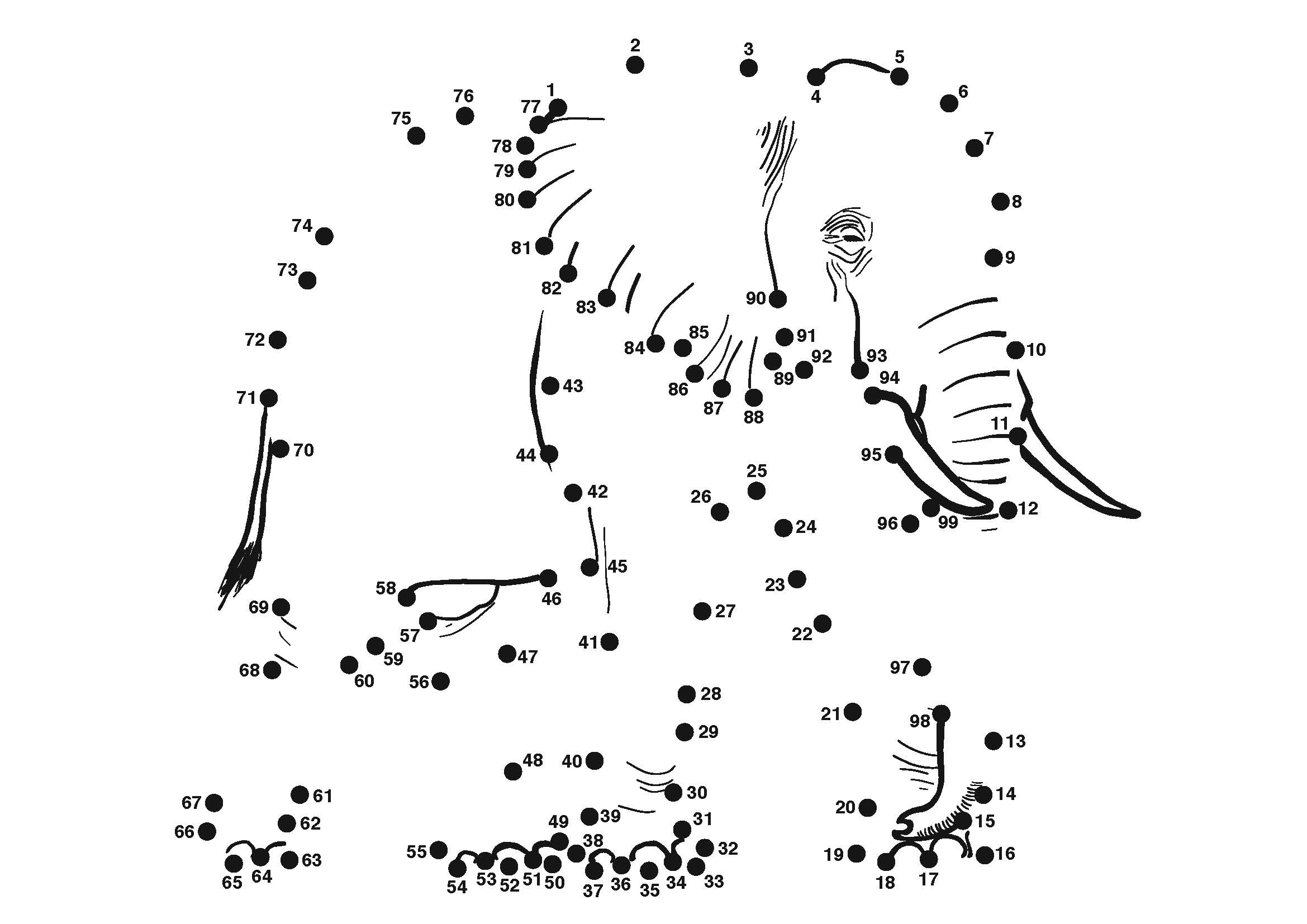

The elephant

Each of the stories alone is, of course, relevant and interesting. They, however, become dramatically more relevant and interesting when seen in the context of the mega-event we that is taking place in our time.

The role of this metaphorical image, the elephant, is to point to a "quantum leap" in relevance and interest, which specific insights and actions can achieve when presented as essential elements of a spectacularly large event—"a great cultural revival".

The elephant

Imagine the 20th century's visionary thinkers as those proverbial blind-folded men touching an elephant. We hear them talk about things like "a fan", "a water hose" and "a tree trunk". But they don't make sense, and we ignore them.

Everything changes when we realize that they are really talking about the ear, the trunk and the leg of an imposingly large exotic animal, which nobody has yet had a chance to see—a whole new order of things, or cultural and social paradigm!

A spectacle

The effect of the five insights is to orchestrate this act of 'connecting the dots'—so that the spectacular event we are part of, this exotic 'animal', the new 'destination' toward which we will now "change course" becomes clearly visible.

A side effect is that the academic results once again become interesting and relevant. In this newly created context, they acquire a whole new meaning; and agency!

Reinstitution of the myth and the parable

Both had a core function in the traditional culture. We reinstate this function.

We also revitalize traditional myths and parables, from religious traditions and beyond. The key is to not see them as literally true (in the holotopia scheme of things nothing is), but as artifacts communicating culturally significant messages.

Post-post-structuralism

The structuralists undertook to bring rigor to the study of cultural artifacts. The post-structuralists "deconstructed" their efforts, by observing that there is no such thing as "real meaning"; and that the meaning of cultural artifacts is open to interpretation.

This evolution may be taken a step further. What interests us is not what, for instance, Bourdieu "really saw" and wanted to communicate. We acknowledge (with the post-structuralists), that even Bourdieu would not be able to tell us that, if he were still around. We acknowledge, however, that Bourdieu saw something that invited a different interpretation and way of thinking than what was common; and did what he could to explain it within the old paradigm. Hence we give the study of cultural artifacts not only a sense of rigor, but also a new degree of relevance—by considering them as signs on the road, pointing to an emerging paradigm

Engelbart saw the elephant

While the view of the elephant is composed of a large number of stories, one of them—the incredible history of Doug (Engelbart)—is epigrammatic. It is not only a spectacular story—how the Silicon Valley failed to understand or even hear its "giant in residence", even after having recognized him as that; it is also a parable pointing to many of the elements we want to highlight by telling these stories—not least the social psychology and dynamics that 'hold Galilei in house arrest'.

This story also inspired us to use this metaphor: Engelbart saw 'the elephant' already in 1951—and spent a six decades-long career painstakingly trying to show him to us.

He did not succeed!

Engelbart passed away with only a meager (computer) mouse in his hand (to his credit)!

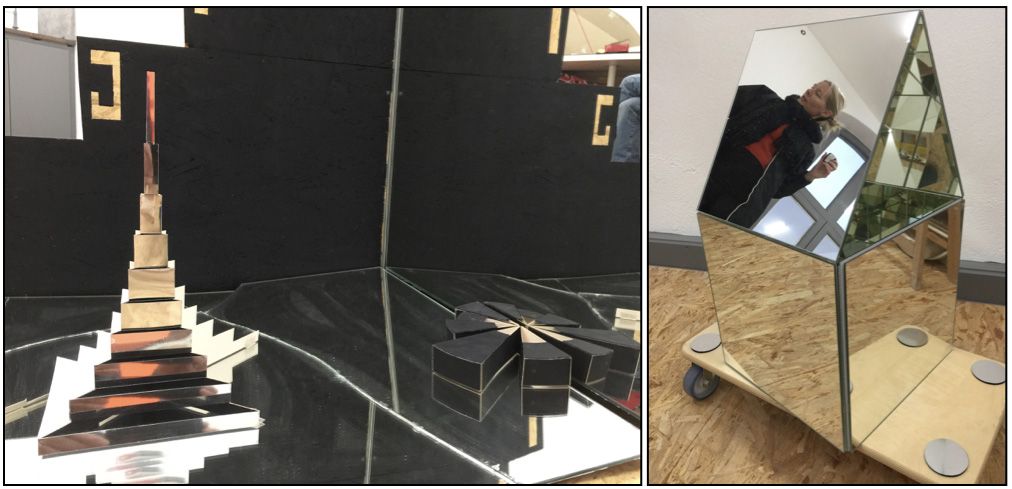

Mirror

Details from Vibeke Jensen's Berlin studio.

As a society, and as the academic tradition in particular—which has been guiding our society along the homo sapiens evolutionary path—we are now standing in front of the mirror. We are invited to self-reflect. And to find a way through.

In holotopia the mirror is a symbolic object with a variety of connotations. As an art object, is carries a spectrum of possibilities. And as a tactical object—the mirror lets us employ the symbolic language of the arts, to code culturally transformative messages.

Abolition of reification

The mirror brings an end to reifications of all kinds—of the power-laden way in which we see the world (or socialized reality created by power structure), our "scientific worldview" (or narrow frame), our ways of handling knowledge (our functionally impaired collective mind ), our likes and dislikes (convenience paradox).

Reinstitution of curiosity and accountability

When reification is removed, we are left with the question: "What do we really know, about the questions that matter?" The answer we'll reach may now seem preposterous, or shocking. So instead of jumping to a conclusion, we share a story. It is intended to serve as a parable for the inception of the Academia—and hence of the academic tradition.

The trial of Socrates as told in Plato's Apology

Someone went to Delphi and asked the Oracle about the wisest man in Athens; came back with the answer that it was Socrates. When the news reached him, Socrates was perplexed, because he did not consider himself knowledgeable or wise. And yet God does not lie! So he endeavored to find a solution to this puzzle, by seeking out and examining his contemporaries who were reputed as knowledgeable and wise. Surely he would find them superior! But the result was that he didn't. They knew just as little as Socrates did. The difference was, however, that they believed they knew a lot more. In this way Socrates resolved the puzzle of the Oracle: A wiser man is not the one who knows more than others—but the one who knows the limits of his knowledge.

Our situation now demands that we revive this original academic spirit. A cultural revival will once again follow.

Dialogs

<h3>The dialog is an entirely different way of communicating

We must emphasize this at once:

While the word "dialog" is common, the dialog is an entirely uncommon way of communicating.

What we are calling the dialog is as different from the conventional academic and political debating, as the holotopia is different from our contemporary social and cultural order of things

While through Socrates and Plato the dialog has been a foundation stone of the academic tradition, David Bohm gave this word a completely new meaning—which we have undertaken to adopt and to develop further. The Bohm Dialogue website provides an excellent introduction, so it will suffice to point to it by echoing a couple of quotations. The first one is by Bohm himself.

There is a possibility of creativity in the socio-cultural domain which has not been explored by any known society adequately.

We let it point to the fact that to Bohm the "dialogue" was an instrument of socio-cultural therapy, leading to a whole new co-creative way of being together. Bohm considered the dialogue to be a necessary step toward unraveling our contemporary situation.

The second quotation is a concise explanation of Bohm's idea by the creators of the website.

Dialogue, as David Bohm envisioned it, is a radically new approach to group interaction, with an emphasis on listening and observation, while suspending the culturally conditioned judgments and impulses that we all have. This unique and creative form of dialogue is necessary and urgent if humanity is to generate a coherent culture that will allow for its continued survival.

As this may suggest, the dialog is conceived as a direct antidote to power structure-induced socialized reality.

The dialog is the message

By creating the dialogs and engaging in them, we transform both our collective mind, and the way in which we are together.

Here the medium truly is the message. When we are engaged in a genuine dialog about a core contemporary issue—in the context of the relevant academic and other insights (represented in our current holotopia prototype by the five insights)—we are already part of a functioning collective mind. We are already applying our collective creativity toward evolving or federating our collective knowledge further.

The dialog is a profound tradition

Although the dialog, as Bohm envisioned it, is a relatively recent development, it is already a deep and profound tradition—and we here illustrate that by only pointing to some references and stories.

- Bohm's own inspiration (story has it) is significant. Allegedly, Bohm was moved to create the "dialogue" when he saw how Einstein and Bohr, who were once good friends, and their entourages, were unable to communicate at Princeton. (The roots of this disagreement are interesting for holotopia although perhaps less for the dialog: Einstein's "God does not play Dice" criticism of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum theory; and Bohr's reply "Einstein, stop telling god what to do!" While in our prototype Einstein has the role of the icon of "modern science", in this instance it was clearly Bohr and not Einstein who represented the epistemological position we are supporting. But Einstein later reversed his position— in "Autobiographical Notes", where Einstein made his epistemological testimony, on a similar note as Heisenberg did in Physics and Philosophy. While the foundations of the holoscope have been carefully federated, it has turned out that federating "Autobiographical Notes" is sufficient, see Federation through Images).

- There is a little known red thread in the history of The Club of Rome; the story could have been entirely different: Özbekhan, Jantsch and Christakis, who co-founded The Club with Peccei and King, and wrote its statement of purpose, were in disagreement with the course it took in 1970 (with The Limits to Growth study) and left. Alexander Christakis, the only surviving member of this trio, is now continuing their line of work as the President of the Institute for 21st Century Agoras. "The Institute for 21st Century Agoras is credited for the formalization of the science of Structured dialogic design." (Wikipedia).

- Bela H. Banathy, whom we've mentioned as the champion of "Guided Evolution of Society" among the systems scientists, extensively experimented with the dialog. With Jenlink he co-edited two large and most valuable volumes about the dialogue.

- In 1983 Michel Foucault gave a seminar at the UC Berkeley. What will this European historian of ideas par excellence choose to tell the young Americans? Foucault spent six lectures talking about an obscure Greek word, parrhesia. The key point here is that the dialog (as relationship with the people, the world and the truth) is a radical alternative to the "adiaphorized" or "instrumental" thinking, which has become common. An interesting point is that the Greeks considered parrhesia to be an essential element of democracy—which our contemporary democracies have increasingly failed to adopt and emulate. Both Socrates and Galilei were exemplars of "parrhesiastes" (a person who lives and uses parrhesia; the latter chose to retreat on this position a bit, and save his life).

[P]arrhesiastes is someone who takes a risk. Of course, this risk is not always a risk of life. When, for example, you see a friend doing something wrong and you risk incurring his anger by telling him he is wrong, you are acting as a parrhesiastes. In such a case, you do not risk your life, but you may hurt him by your remarks, and your friendship may consequently suffer for it. If, in a political debate, an orator risks losing his popularity because his opinions are contrary to the majority's opinion, or his opinions may usher in a political scandal, he uses parrhesia. Parrhesia, then, is linked to courage in the face of danger: it demands the courage to speak the truth in spite of some danger. And in its extreme form, telling the truth takes place in the "game" of life or death.

- A whole new chapter in the evolution of the dialogue was made possible by the new information technology. We illustrate an already developed research frontier by pointing to Jeff Conklin's book "Dialogue Mapping: Creating Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems", where Bohm dialogue tradition is combined with Issue Based Information Systems, which Kunz and Rittel developed at UC Berkeley in the 1960s. The Debategraph, which is also developed by combining those two traditions, is actively transforming the way in which issues are collectively understood.