Difference between revisions of "Holotopia"

From Knowledge Federation

m |

m |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <!-- ;) | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 295: | Line 296: | ||

<p>To an academic researcher, it may feel disheartening to see so many best ideas of our best minds ignored. Why publish more—if even the most <em>elementary</em> insight that our field has produced, the one that <em>motivated</em> our field and our work, has not yet been communicated to the public?</p> | <p>To an academic researcher, it may feel disheartening to see so many best ideas of our best minds ignored. Why publish more—if even the most <em>elementary</em> insight that our field has produced, the one that <em>motivated</em> our field and our work, has not yet been communicated to the public?</p> | ||

| − | <p>This sentiment is transformed into <em>holotopian</em> optimism | + | <p>This sentiment is transformed into <em>holotopian</em> optimism when we look at 'the other side of the coin'—the creative frontier that is opening up. We are invited to, we are indeed <em>obliged</em> to reinvent <em>the systems in which we live and work</em>, by recreating the very communication that holds them together. Including, of course, our own, academic system, and the way in which it interoperates with other systems—<em>or fails</em> to interoperate. </p> |

| − | < | + | <p>Optimism will turn into enthusiasm, when we consider also <em>this</em> commonly ignored fact:</p> |

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The information technology we now commonly use to communicate with the world was <em>created</em> to enable a paradigm change on that very frontier.</blockquote> |

| − | < | + | <p>'Electricity', and the 'lightbulb', have just been created—in order to <em>enable</em> the development of the new kinds of 'socio-technical machinery' that our society now urgently needs.</p> |

| − | <p>Vannevar Bush pointed to the need for new paradigm already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" really means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that—given the vast volumes of our information—our knowledge work must be organized <em>in a way that enables us to benefit from each other's thinking</em>. That technology and processes must be devised to enable us to in effect "connect the dots" or think <em>together</em>, as a single mind does. Bush described a <em>prototype</em> system called "memex", which was based on microfilm as technology.</p> | + | <p>Vannevar Bush pointed to the need for this new paradigm already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" really means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that—given the vast volumes of our information—our knowledge work must be organized <em>in a way that enables us to benefit from each other's thinking</em>. That technology and processes must be devised to enable us to in effect "connect the dots" or think <em>together</em>, as a single mind does. Bush described a <em>prototype</em> system called "memex", which was based on microfilm as technology.</p> |

<p>Douglas Engelbart, however, took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected together into a network—then the overall result is that we are connected together as the cells in a human organism are connected by the nervous system. </p> | <p>Douglas Engelbart, however, took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected together into a network—then the overall result is that we are connected together as the cells in a human organism are connected by the nervous system. </p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Notice that the earlier innovations in this area—including both the clay tablets and the printing press—required that a physical object be <em>transported</em>; this new technology allows us to "create, integrate and apply knowledge" <em>concurrently</em>, as cells in a human nervous system do.</p> |

<blockquote> We can now develop insights and solutions <em>together</em>! We can have results <em>instantly</em>!</blockquote> | <blockquote> We can now develop insights and solutions <em>together</em>! We can have results <em>instantly</em>!</blockquote> | ||

| − | <p>Engelbart | + | <p>Engelbart saw in this new technology exactly what we need to become able to handle the "complexity times urgency" of our problems, which grows at an accelerated rate. </p> |

| − | <p>[https://youtu.be/cRdRSWDefgw This three minute video clip], which we called "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", offers an opportunity for a pause. Imagine the effects of improving the planetary <em> | + | <p>[https://youtu.be/cRdRSWDefgw This three minute video clip], which we called "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", offers an opportunity for a pause. Imagine the effects of improving the planetary <em>systems</em>, and our "development, integration and application of knowledge" to begin with. Imagine "the effects of getting 5% better", Engelbart commented with a smile. Then our old man put his fingers on his forehead, and looked up: "I've always imagined that the potential was... large..." The potential is not only large, it is <em>staggering</em>. The improvement that is both necessary and possible is <em>qualitative</em>—from a system that doesn't work, to one that does.</p> |

<p>To Engelbart's dismay, this new "collective nervous system" ended up being use to only make the <em>old</em> processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that <em>broadcast</em> information. </p> | <p>To Engelbart's dismay, this new "collective nervous system" ended up being use to only make the <em>old</em> processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that <em>broadcast</em> information. </p> | ||

| Line 321: | Line 322: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | <blockquote>The above observation by Anthony Giddens points to the impact this had on culture; and on "human quality".</blockquote> | + | <blockquote>The above observation by Anthony Giddens points to the impact this has had on our culture; and on "human quality".</blockquote> |

<p>Dazzled by an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.</p> | <p>Dazzled by an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.</p> | ||

| − | <p>But | + | <p>But that is exactly what <em>binds us</em> to <em>power structure</em>. </p> |

<h3>Remedy</h3> | <h3>Remedy</h3> | ||

| − | <blockquote><em>What is to be done</em>, if we should | + | <blockquote><em>What is to be done</em>, if we should become able to use the new technology as it's meant to be used—to change our <em>collective mind</em>?</blockquote> |

| − | <p>Engelbart left us a clear answer in the opening slides of his "A Call to Action" presentation, which were prepared for a 2007 panel that Google organized to share his vision to the world | + | <p>Engelbart left us a clear answer in the opening slides of his "A Call to Action" presentation, which were prepared for a 2007 panel that Google organized to share his vision to the world (but not shown!).</p> |

<p> | <p> | ||

| Line 345: | Line 346: | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Yes, it was the <em>systemic innovation</em>, or "making things whole", he was pointing to. Engelbart even published an original <em>systemic innovation</em> methodology <em>already in 1962</em>—six years before Jantsch and others created theirs.</p> |

| − | <p>Engelbart also made it clear what | + | <p>Engelbart also made it clear what our next step needed to be—by which the spell of the <em>Wiener's paradox</em> is to be broken. He called it "bootstrapping"—and we adapted that as one of our <em>keywords</em>. His point was that only <em>writing</em> about what needs to be done (the tie between information and action having been broken) would not have an effect. <em>Bootstrapping</em> means that we <em>act</em>—and either <em>create</em> a new system with the material of our own minds and bodies, or help others do that.</p> |

| − | <p>What we are calling <em>knowledge federation</em> is the | + | <p>What we are calling <em>knowledge federation</em> is a collection of social processes—which constitute the operation of a <em>collective mind</em> that our technology enables, and our society requires.</p> |

<p>The Knowledge Federation <em>transdiscipline</em> was created by an act of <em>bootstrapping</em>, to enable <em>bootstrapping</em>. Originally, we were a community of knowledge media researchers and developers, developing the <em>collective mind</em> solutions that the new technology enables. Already at our first meeting, in 2008, we realized that the technology that we and our colleagues were developing has the potential to change our <em>collective mind</em>; but that to realize that potential, we need to self-organize differently.</p> | <p>The Knowledge Federation <em>transdiscipline</em> was created by an act of <em>bootstrapping</em>, to enable <em>bootstrapping</em>. Originally, we were a community of knowledge media researchers and developers, developing the <em>collective mind</em> solutions that the new technology enables. Already at our first meeting, in 2008, we realized that the technology that we and our colleagues were developing has the potential to change our <em>collective mind</em>; but that to realize that potential, we need to self-organize differently.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- XXX | ||

<p>Ever since then have been <em>bootstrapping</em>, by developing <em>prototypes</em> with and for various communities and situations.</p> | <p>Ever since then have been <em>bootstrapping</em>, by developing <em>prototypes</em> with and for various communities and situations.</p> | ||

Revision as of 05:22, 19 August 2020

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

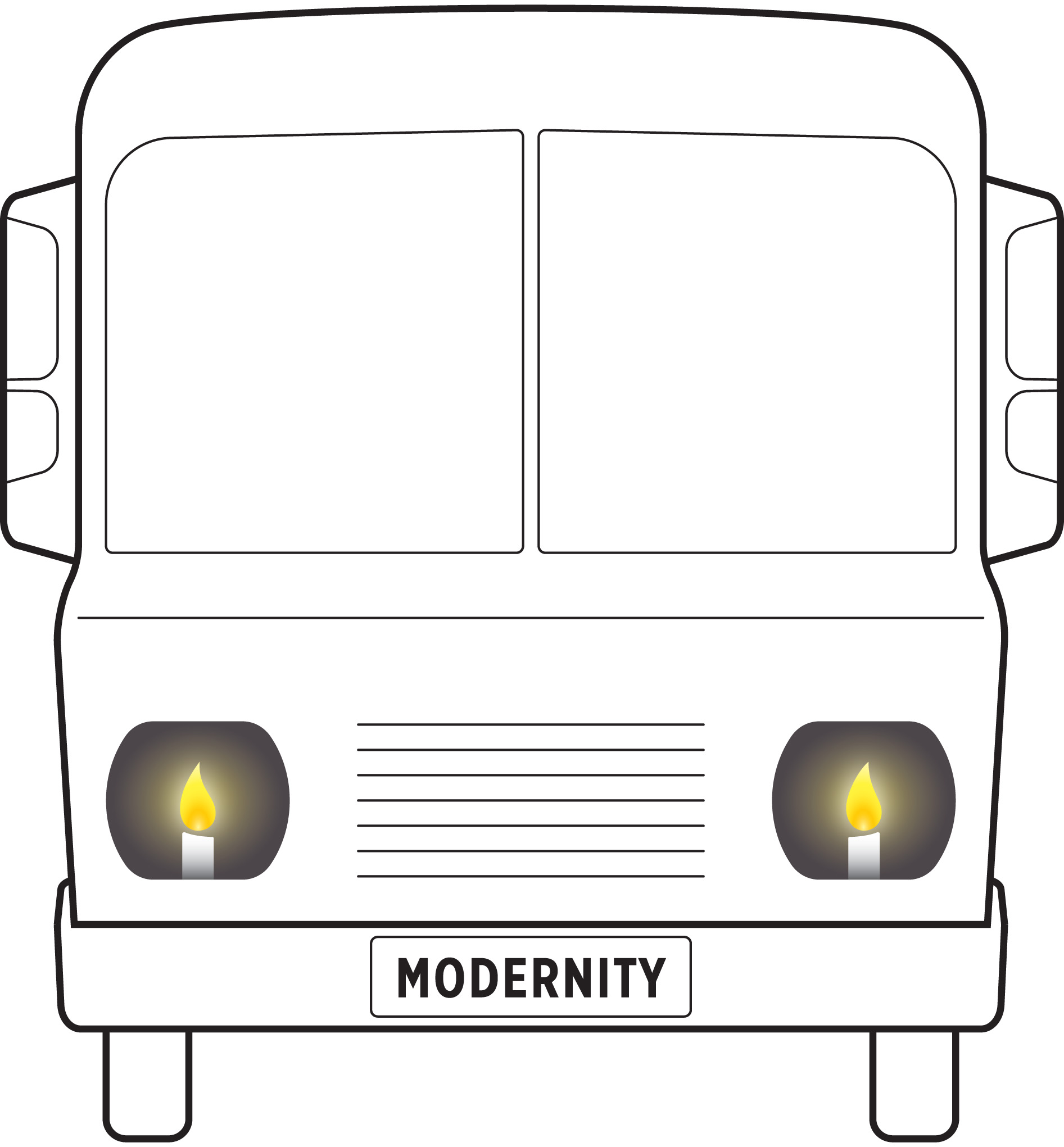

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.