Difference between revisions of "Holotopia"

m |

m |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

<p>The <em>holotopia</em> is different in spirit from them all. It is a <em>more</em> attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the <em>holotopia</em> is readily realizable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.</p> | <p>The <em>holotopia</em> is different in spirit from them all. It is a <em>more</em> attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the <em>holotopia</em> is readily realizable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.</p> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>The <em>holotopia</em> vision is made concrete in terms of <em>five insights</em>, as explained below.</blockquote> |

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

<p><em>What do we need to do</em> to change course toward the <em>holotopia</em>?</p> | <p><em>What do we need to do</em> to change course toward the <em>holotopia</em>?</p> | ||

| − | <blockquote> | + | <blockquote>The <em>five insights</em> point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things [[Wholeness|<em>whole</em>]].</blockquote> |

<p>This principle is suggested by the <em>holotopia</em>'s very name. And also by the Modernity <em>ideogram</em>. Instead of <em>reifying</em> our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the [[Wholeness|<em>wholeness</em>]] of it all. </p> | <p>This principle is suggested by the <em>holotopia</em>'s very name. And also by the Modernity <em>ideogram</em>. Instead of <em>reifying</em> our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the [[Wholeness|<em>wholeness</em>]] of it all. </p> | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

<div class="col-md-7"> | <div class="col-md-7"> | ||

<p>"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost <em>the sense of the whole</em>." </p> | <p>"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost <em>the sense of the whole</em>." </p> | ||

| − | <blockquote>To make things | + | |

| + | <blockquote>To make things [[Wholeness|<em>whole</em>]]—<em>we must be able to see them whole</em>! </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

<p>To highlight that the <em>knowledge federation</em> methodology described and implemented in the proposed <em>prototype</em> affords that very capability, to <em>see things whole</em>, in the context of the <em>holotopia</em> we refer to it by the pseudonym <em>holoscope</em>. </p> | <p>To highlight that the <em>knowledge federation</em> methodology described and implemented in the proposed <em>prototype</em> affords that very capability, to <em>see things whole</em>, in the context of the <em>holotopia</em> we refer to it by the pseudonym <em>holoscope</em>. </p> | ||

| − | <p>While characteristics of the <em>holoscope</em>—the design choices or <em>design patterns</em>, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.</p> | + | |

| + | <p>While the characteristics of the <em>holoscope</em>—the design choices or <em>design patterns</em>, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.</p> | ||

| Line 125: | Line 128: | ||

<blockquote>To see things whole, we must look at all sides.</blockquote> | <blockquote>To see things whole, we must look at all sides.</blockquote> | ||

| − | <p>The <em>holoscope</em> distinguishes itself by allowing for a deliberate creation and choice of <em>multiple</em> ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called <em>scopes</em>. This | + | <p>The <em>holoscope</em> distinguishes itself by allowing for a deliberate creation and choice of <em>multiple</em> ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called <em>scopes</em>. The <em>scopes</em> and the resulting <em>views</em> have a similar function as projections do in technical drawing.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>This <em>modernization</em> of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed <em>creation</em> of the ways in which we look—is suggested by the bus with candle headlights metaphor. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>But this also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not offered as "reality pictures", contending for the "reality" status with one another and with our conventional ones.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>In the <em>holoscope</em>, the legitimacy and coexistence of multiple ways to look at a theme is axiomatic.</blockquote> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>We shall continue to use the conventional language and say that <em>X</em> <em>is</em> <em>Y</em>—although it would be more correct to say that <em>X</em> can or must (also) be seen as <em>Y</em>. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way; and to do that collaboratively, in a [[dialog|<em>dialog</em>]].</p> |

<p>To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of <em>scopes</em>, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy. </p> | <p>To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of <em>scopes</em>, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy. </p> | ||

| Line 133: | Line 142: | ||

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the <em>tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention</em>. The <em>holoscope</em> is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see <em>any</em> chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion. | Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the <em>tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention</em>. The <em>holoscope</em> is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see <em>any</em> chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

<p>To see what we do not see, we take advantage of the insights of others. The <em>holoscope</em> combines scientific and other insights to provide us the vision we need. By deliberately choosing <em>scopes</em>, and taking advantage of this distinguishing feature of the <em>holoscope</em>, we can discover structural defects ('cracks') in some of the core constituting elements of our society or culture, which—when seen in our habitual ways (or metaphorically 'in the light of the candle')—tend to appear to us as just normal. </p> | <p>To see what we do not see, we take advantage of the insights of others. The <em>holoscope</em> combines scientific and other insights to provide us the vision we need. By deliberately choosing <em>scopes</em>, and taking advantage of this distinguishing feature of the <em>holoscope</em>, we can discover structural defects ('cracks') in some of the core constituting elements of our society or culture, which—when seen in our habitual ways (or metaphorically 'in the light of the candle')—tend to appear to us as just normal. </p> | ||

| Line 139: | Line 149: | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

| − | + | <!-- XXX | |

<div class="page-header" ><h2>Five insights</h2></div> | <div class="page-header" ><h2>Five insights</h2></div> | ||

Revision as of 10:45, 18 August 2020

Contents

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

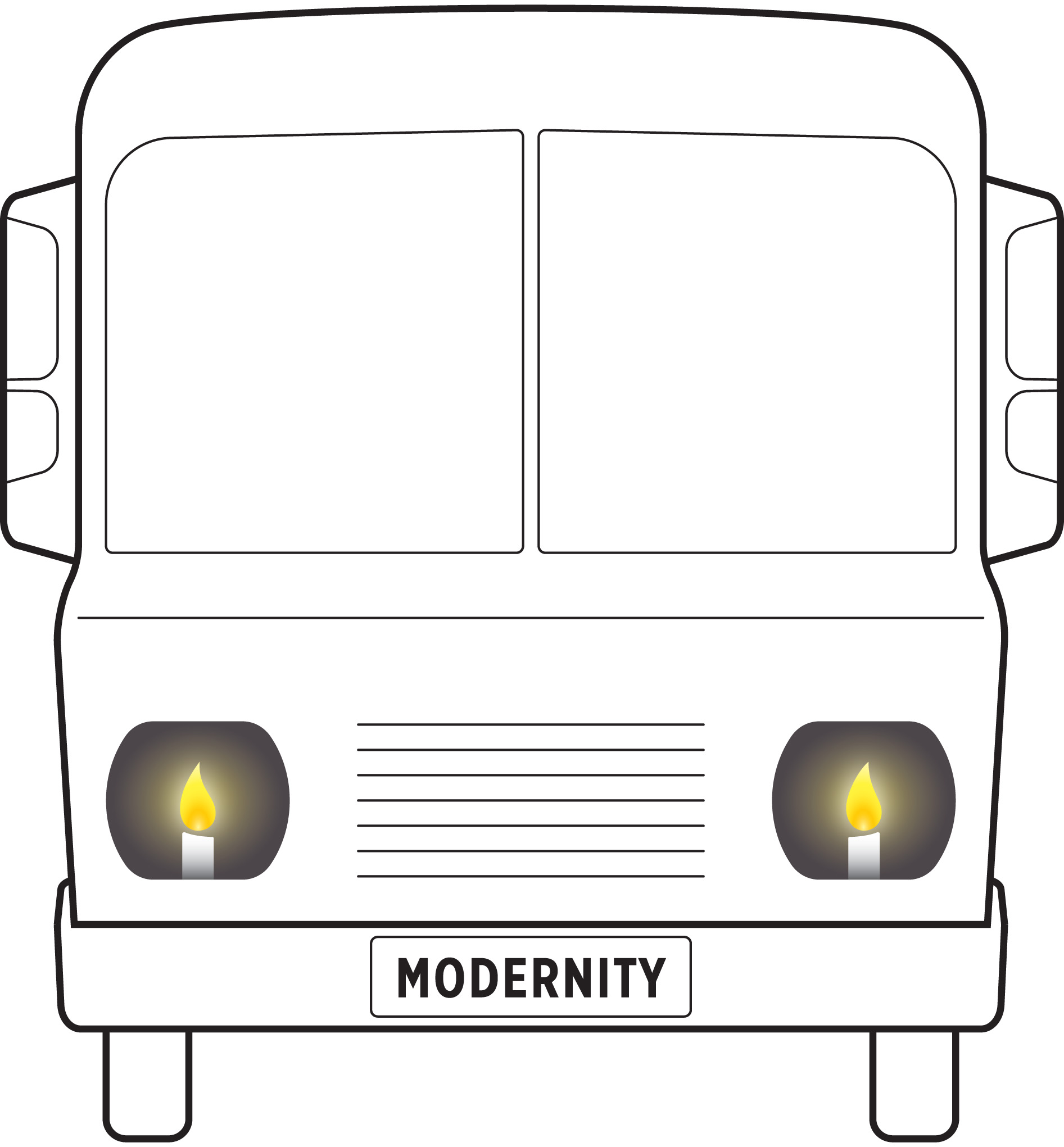

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Our proposal

The core of our knowledge federation proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of knowledge federation, where initial answers to relevant questions are presented, and in part implemented in practice.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field, and a real-life praxis (informed practice).

Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

A proof of concept application

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to change course:

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century's thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

Could the change of 'headlights' we are proposing be "a way to change course"?

A vision

Holotopia is a vision of a possible future that emerges when proper light has been turned on.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. But in view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" emerged as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It is a more attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the holotopia is readily realizable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights, as explained below.

A principle

What do we need to do to change course toward the holotopia?

The five insights point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by the holotopia's very name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

A method

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To make things whole—we must be able to see them whole!

To highlight that the knowledge federation methodology described and implemented in the proposed prototype affords that very capability, to see things whole, in the context of the holotopia we refer to it by the pseudonym holoscope.

While the characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

To see things whole, we must look at all sides.

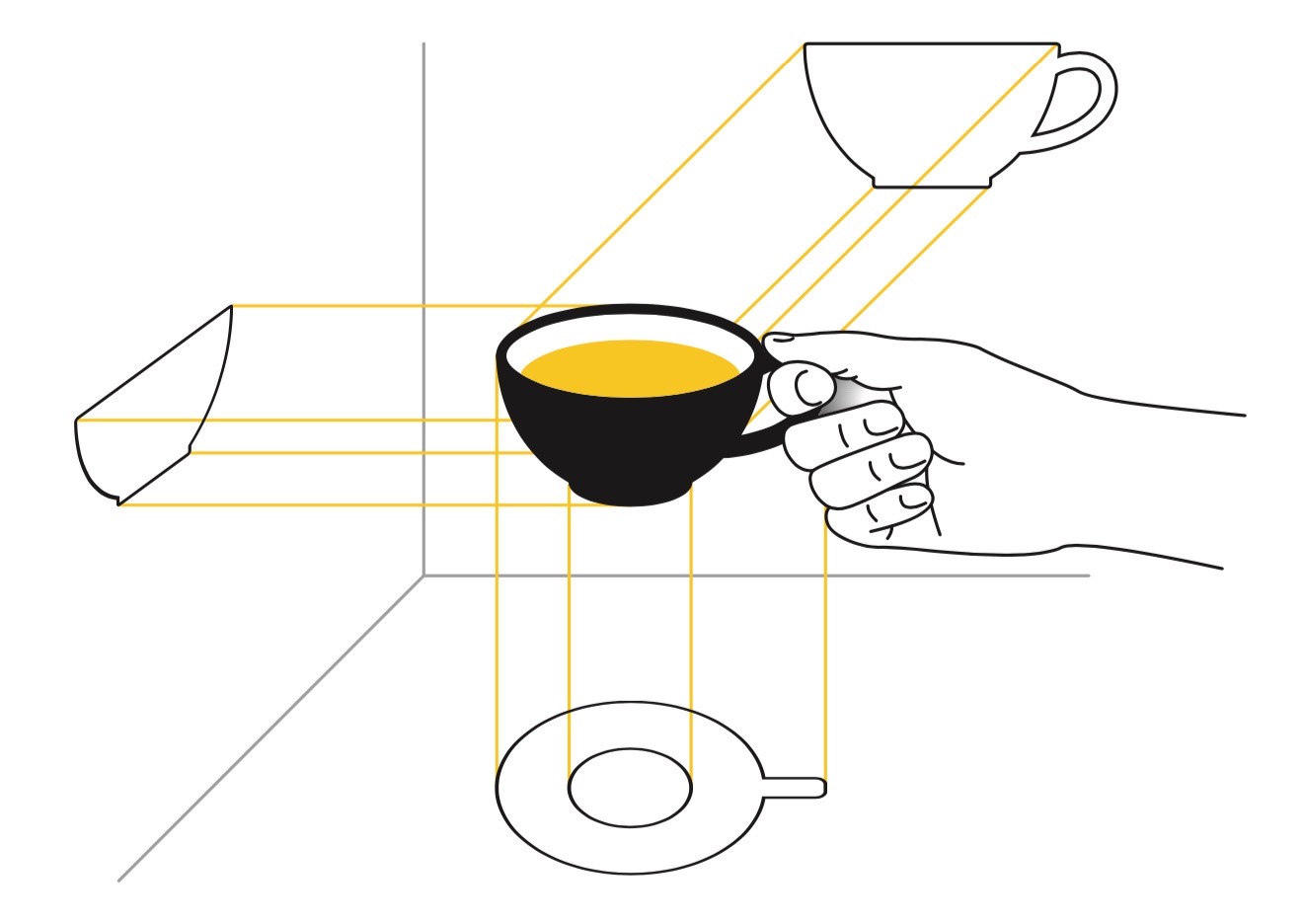

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for a deliberate creation and choice of multiple ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. The scopes and the resulting views have a similar function as projections do in technical drawing.

This modernization of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed creation of the ways in which we look—is suggested by the bus with candle headlights metaphor.

But this also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not offered as "reality pictures", contending for the "reality" status with one another and with our conventional ones.

In the holoscope, the legitimacy and coexistence of multiple ways to look at a theme is axiomatic.

We shall continue to use the conventional language and say that X is Y—although it would be more correct to say that X can or must (also) be seen as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way; and to do that collaboratively, in a dialog.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

To see what we do not see, we take advantage of the insights of others. The holoscope combines scientific and other insights to provide us the vision we need. By deliberately choosing scopes, and taking advantage of this distinguishing feature of the holoscope, we can discover structural defects ('cracks') in some of the core constituting elements of our society or culture, which—when seen in our habitual ways (or metaphorically 'in the light of the candle')—tend to appear to us as just normal.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a cardboard map of a city, and a construction site. By sharing them, we are not making a case for that specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life praxis.