Difference between revisions of "Holotopia"

m |

m |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

<blockquote>The substance of our proposal is a <em>complete</em> [[Holotopia:Prototype|<em>prototype</em>]] of [[Holotopia:Knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]], by which those and other related questions are answered. </blockquote> | <blockquote>The substance of our proposal is a <em>complete</em> [[Holotopia:Prototype|<em>prototype</em>]] of [[Holotopia:Knowledge federation|<em>knowledge federation</em>]], by which those and other related questions are answered. </blockquote> | ||

| − | < | + | <blockquote>Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop <em>knowledge federation</em> as an academic field, and a real-life <em>praxis</em> (informed practice).</blockquote> |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.</blockquote> | ||

</div> </div> | </div> </div> | ||

Revision as of 10:02, 18 August 2020

Imagine...

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

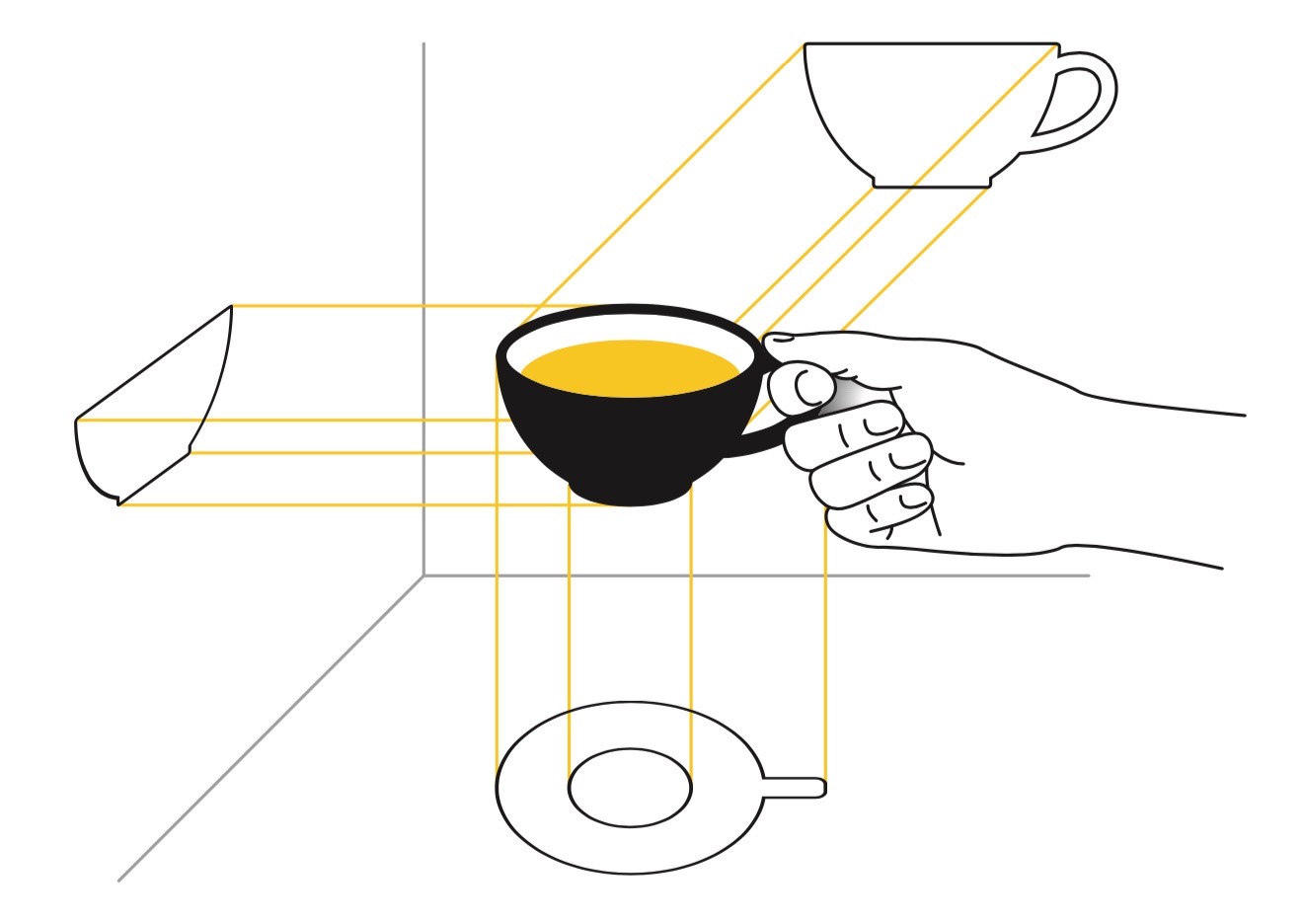

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Our proposal

The core of our knowledge federation proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of knowledge federation, by which those and other related questions are answered.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field, and a real-life praxis (informed practice).

Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

A proof of concept application

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.

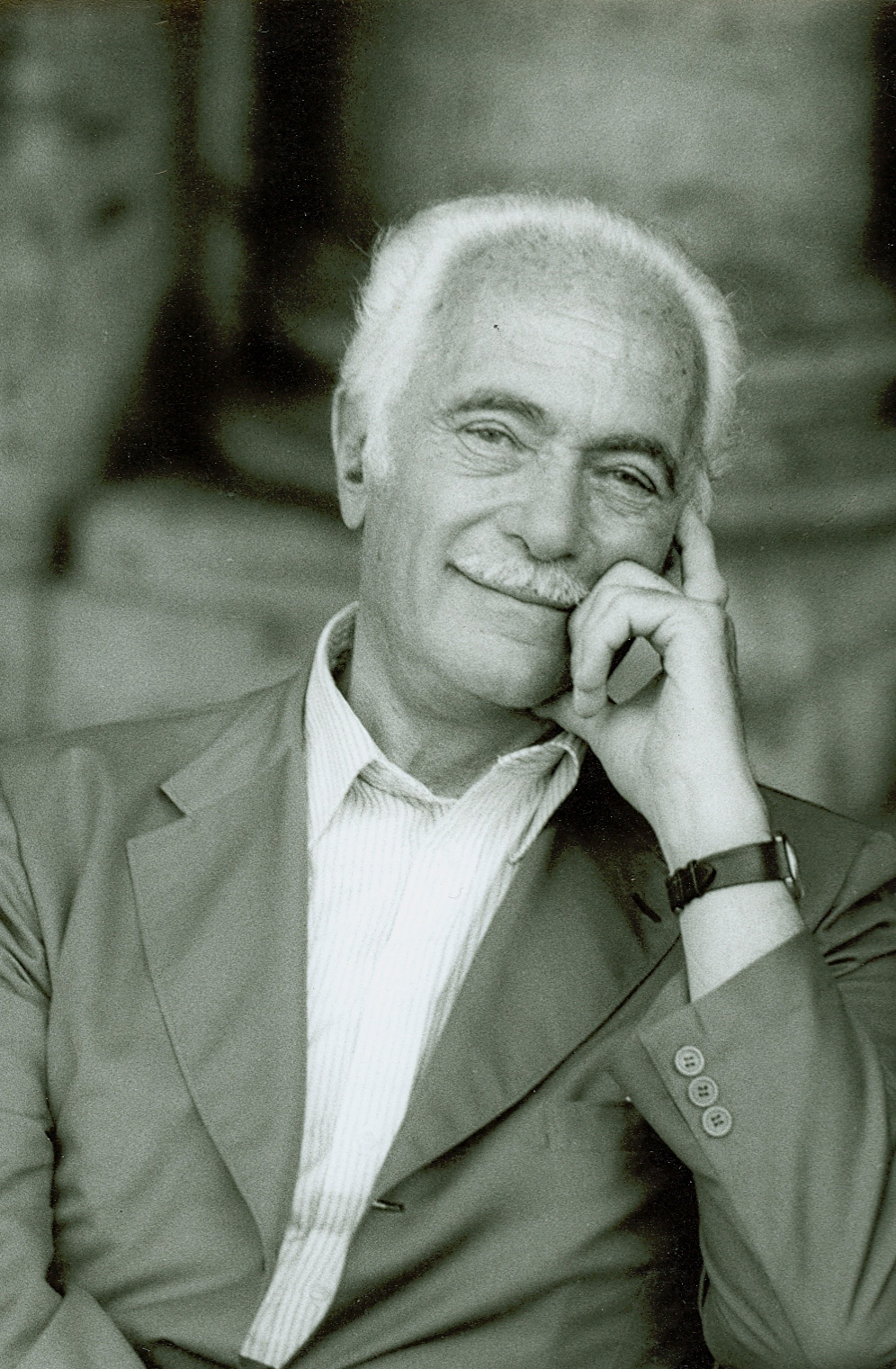

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to change course:

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century's thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

Can the change of 'headlights' we are proposing enable us to "change course"?

A vision

Holotopia is the vision of a possible future that results when proper light has been turned on.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. But in view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" emerged as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It is a more attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the holotopia is readily realizable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights, as explained below.

A principle

What do we need to do to change course toward the holotopia?

From a collection of insights from which the holotopia emerges as a future worth aiming for, we have distilled a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by the holotopia's very name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

A method

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To make things whole—we must be able to see them whole!

To highlight that the knowledge federation methodology described and implemented in the proposed prototype affords that very capability, to see things whole, in the context of the holotopia we refer to it by the pseudonym holoscope.

While characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

To see things whole, we must look at all sides.

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for a deliberate creation and choice of multiple ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. This conscious, free and informed choice of the ways in which we look at the world (as a more "moder" alternative to adhering to the habitual, inherited, reified or traditional ways) is the defining characteristic of the holoscope. The goal is to be able to 'see from all sides', and condense a volume of data to a simple insight that points to correct action ('the cup is whole', or 'the cup has a crack').

It is important to bear in mind that the resulting views are not offered as "reality pictures" contending for the "reality" status with one another and with our conventional ones—but as simplifications similar to projections in technical drawing. We shall continue to use the conventional language and say that X is Y—although it would be more correct to say that X can or must (also) be seen as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way; and to do that collaboratively, in a dialog.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

To see what we do not see, we take advantage of the insights of others. The holoscope combines scientific and other insights to provide us the vision we need. By deliberately choosing scopes, and taking advantage of this distinguishing feature of the holoscope, we can discover structural defects ('cracks') in some of the core constituting elements of our society or culture, which—when seen in our habitual ways (or metaphorically 'in the light of the candle')—tend to appear to us as just normal.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a cardboard map of a city, and a construction site. By sharing them, we are not making a case for that specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life praxis.

Five insights

Scope

Consider the huge momentum with which our civilization is rushing onward.

What new discovery, what technical invention might have a sufficiently large potential impact, to even have a chance to qualify as "a way to change course"?

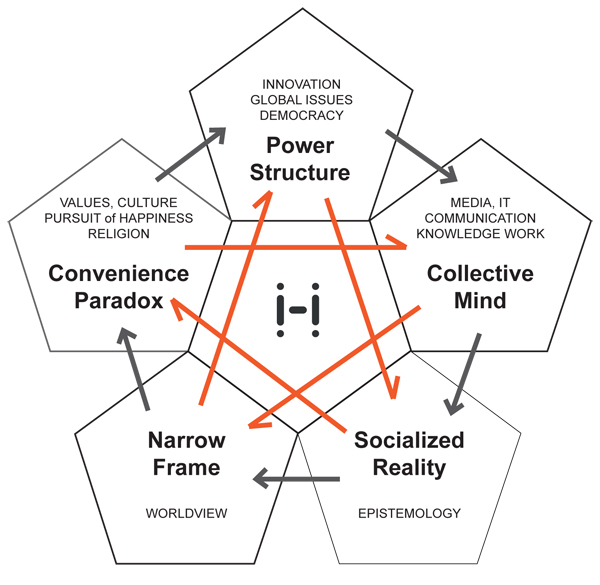

In what follows we use the holoscope as a technical invention, to look at five pivotal domains, which determine the "course":

- Innovation—the way we use our ability to create, and induce change

- Communication—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is created and used

- Epistemology—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning, which determine "the relationship we have with information"

- Method—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life, which determines "the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it"

- Values, or how we "pursue happiness"—which in a free society directly determine the course

In each of them, by using the holoscope to combine existing research results into an insight, we discover a structural defect, which has led to perceived problems; including those problems that now demand that we "change course".

In each of the cases, we find, also by combining published insights, a basic principle or a rule of thumb that has been ignored and violated—which led to the structural defect.

In each of the cases, we see how the structural defect can be remedied by using the corresponding principle; and that this scientific approach to problems (where we don't merely treat symptoms, but use develop and use knowledge to see and handle its physiological and anatomical causes) leads to improvements that are well beyond mere removal of symptoms.

The holotopia vision results.

A sixth insight then follows—that we already own all the information needed to take care of our problems. And that our basic problem is that we don't use it—because "the tie between information and action has been severed". And hence that the key to solution, the "systemic leverage point" for "changing course" and continuing to evolve culturally and socially, in a new way, is the same as it was in Galilei's time—we must "change the relationship we have with information"

A case for our proposal is thereby also made.

In the spirit of the holoscope, we here only summarize each of the five insights—and provide evidence and details separately.

Scope

What do we need to do, to become able to "change course"?

"Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it", observed Peccei.

We look at the way in which man uses his power to innovate (create, and induce change).

We readily observe that we use competition or "survival of the fittest" to orient innovation and choose the way; not information, not "making things whole". The popular belief that "free competition" (on the "free market" of goods, ideas and policies) will serve us best, makes our democracies elect the leaders who represent that view. But is that belief warranted?

Genuine revolutions bring new ways to see freedom and power; holotopia is no exception.

We offer this keyword, power structure, as a means to that end. Think of the power structure as a new way to conceive of the intuitive notion "power holder"—an entity that might take away our freedom; or use its power to harm us, and be our "enemy".

While the nature of the power structure will become clear as we go along, imagine them, to begin with, as institutions; or more accurately, as the systems in which we live and work (which we shall here simply call systems).

Notice that systems have an immense power—over us, because we have to adapt to them to be able to live and work; and over our environment, because by organizing us and using us in a certain specific way, they decide what the effects of our work will be.

The power structures determine whether the effects of our efforts will be problems, or solutions.

Diagnosis

How suitable are the systems in which we live and work for their all-important role?

Evidence shows that they waste a lion's share of our resources. And that they either cause our problems, or make us incapable of solving them.

The reason is the intrinsic nature of evolution, as Richard Dawkins explained it in "The Selfish Gene".

"Survival of the fittest" favors the systems that are by nature predatory; not the ones that are useful.

This excerpt from Joel Bakan's documentary "The Corporation" (which Bakan as a law professor created to federate an insight he considered essential) explains how the most powerful institution on our planet evolved to be a perfect "externalizing machine" ("Externalizing" means maximizing profits by letting someone else bear the costs, such as the people and the environment), just as the shark evolved to be a perfect "killing machine". This scene from Sidney Pollack's 1969 film "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" will illustrate how our systems affect our own condition.

Why do we put up with such systems? Why don't we treat them as we treat other human-made things—by adapting them to the purposes that need to be served?

The reasons are interesting, and in holotopia they'll be a recurring theme.

One of them we have already seen: We do not see things whole. We don't see systems when we look in conventional ways—as we don't see the mountain on which we are walking.

A reason why we ignore the possibility of adapting the systems in which we live and work to the roles they have in our society is that they perform for us a different role—they provide a stable structure to our various power battles and turf strifes. Within our system, they provide us "objective" and "fair" criteria for competing for positions; and in the world outside, they give us as a system the "competitive edge".

This, for instance, is the reason why the media corporations don't combine their resources and give us the awareness we need; they must compete with one another—and use whatever means are the most "cost-effective" for acquiring our attention.

The most interesting reason—which we will revisit and understand more thoroughly below—is that the power structures have the power to socialize us in ways that suit their interests. This basic idea, of socialization, can however be understood if we think of our systems as providing a certain ecology, which over a long run shapes our values, and our "human quality". The business of business is just business—and business requires that we think and behave in a certain way. We either bend to our "job requirements", or get replaced. The overall systemic effect is the same.

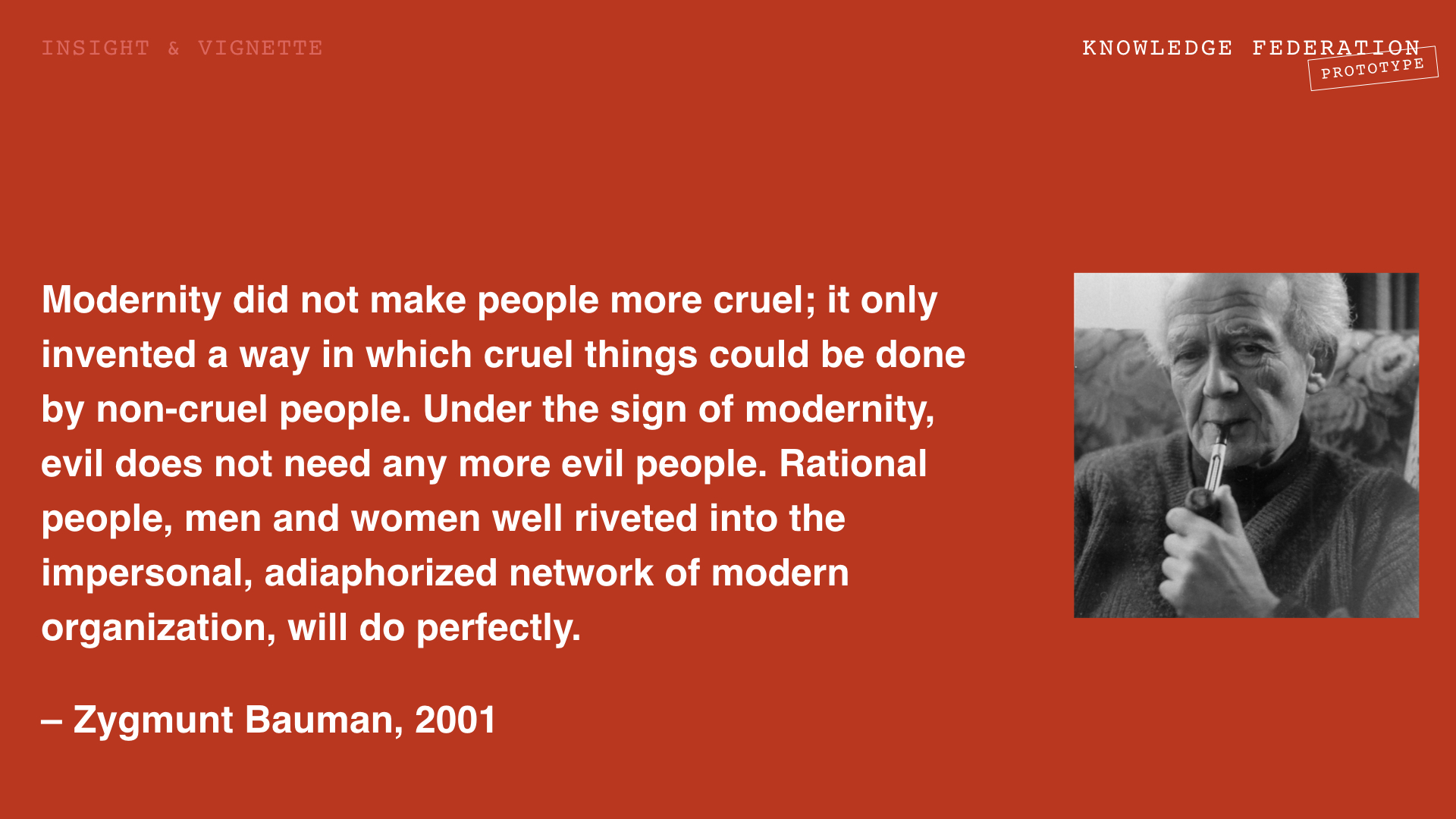

An overall result, as Bauman diagnosed it, is that bad intentions are no longer required for cruelty and evil to result. The power structures can co-opt our sense of duty and commitment; and even our heroism and honor.

Zygmunt Bauman's key insight, that the concentration camp was only a special case, however extreme, of (what we are calling) the power structure, needs to be carefully understood. Even the concentration camp employees were only conscientiously "doing their job", in a system whose nature and purpose was beyond the reach of their ethical sensibility, and certainly beyond their power to change.

While our ethical sensibilities are focused on the power structures of yesterday, we are committing (in all innocence, by only "doing our job" within the systems we belong to) the greatest massive crime in human history.

Our civilization is not "on the collision course with nature" because someone violated the rules—but because we follow them.

Remedy

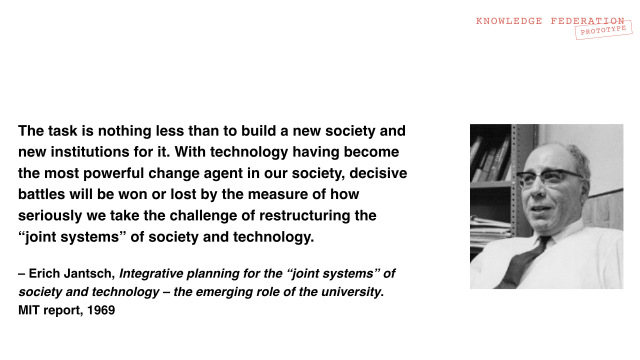

The fact that we will not "solve our problems" unless we learned to perceive and comprehend our systems, and adapt them to their contemporary roles and our contemporary challenges has not remained unnoticed. Alredy in 1948, in his seminal Cybernetics, Norbert Wiener explained why competition cannot replace 'headlights and steering'. Cybernetics was envisioned as a transdisciplinary academic effort to help us understand systems, so that we may adapt their structure to the functions they must perform.

The very first step the founders of The Club of Rome did after its inception in 1968 was to convene a team of experts, in Bellagio, Italy, and develop an academic methodology and a corresponding practical way to change systems. They gave "making things whole" on the scale of socio-technical systems the name "systemic innovation"—and we adapted that as one of our keywords.

In 2010, Knowledge Federation began to self-organize to become able to continue this most timely line of work. The procedure that resulted is simple: We create a prototype of a system, and organize a transdisciplinary community and project around it, to update it continuously. This enables the insights reached in the participating disciplines to have real or systemic impact directly.

Our very first project of this kind, the Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism in 2011, developed a prototype of a public informing that turns perceived problems (that people report directly, through citizen journalism) into systemic understanding of causes and recommendations for action (developed by involving academic and other domain experts, and explained by a communication design team).

The prototypes don't only render systemic solutions into an actionable form (and serve as research 'results'); they are already implemented in practice, and hence serve both as interventions (a way to restore agency to information), and as 'experiments', which allow us to see what works in practice, and what still needs to be improved. The prototype we have just mentioned readily showed that the senior journalists and journalism experts we brought together to represent their domain cannot change their system. What they, however, can and need to do is empower their junior colleagues to do that. A year later we created The Game-Changing Game as a generic way to do that—and as a "practical way to craft the future". We subsequently created The Club of Zagreb, as a necessary (according to this insight) update to The Club of Rome, in its all-important mission. The Holotopia project, of course, builds further on this line of work.

Our portfolio contains about forty prototypes, each of which might serve illustrate systemic innovation in a specific domain. Each of them is composed by weaving together design patterns, which are problem-solution pairs. In this holotopian approach to research, a design pattern roughly corresponds to a discovery (of a structural problem or issue), followed by an innovation (elaboration and real-life implementation of its technical solution). Once created, a design pattern can be adapted to other design challenges and domains.

A canonical example is the Collaborology prototype in education. Of about a dozen design patterns it embodies, we here only mention a few, to illustrate this approach and its advantages. An education that prepares people for yesterday's professions, and only in a certain stage of life, is obviously a hindrance to systemic change. Collaborology offers an education that is in every sense flexible (self-guided, life-long...), and in an area of interest that is spot-on (collaboration, as enabled by technology, is as we shall see the enabler of systemic innovation, as well as the core theme of knowledge federation). By being collaboratively created itself (the course is created and taught by a network of international experts, and offered to learners world-wide), the economies of scale result that dramatically reduce effort and quantity, and enable the production of quality. At the same time, the Collaborology prototype provides a sustainable business model for developing and disseminating a new and up-to-date body of knowledge about any theme of interest. By conceiving the course as a design project, where everyone collaborates on co-creating the learning resources, the students get a chance to exercise the relevant sides of their "human quality". In this way, the students also acquire an essential role (as 'bacteria' extracting 'nutrients') in the resulting 'knowledge-work ecosystem'.

Scope

If our next evolutionary task is to make institutions or systems whole—where shall we begin?

The handling of information, or metaphorically our society's 'headlights', suggests itself as the answer for several reasons.

One of the reasons is obvious: If we should use information as guiding light and not competition, our information will need to be different.

Norbert Wiener contributed another reason: In social systems, communication is what turns a collection of independent individuals into a system. In his 1948 book Wiener talked about the communication in ants and bees to make that point. Furthermore, "the tie between information and action" is the key property of a system, which cybernetics invites us to focus on. The full title of Wiener's book was "Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine". To be able to correct their behavior and maintain inner and outer balance, and to "change course" when the circumstances demand that (Wiener used the technical term "homeostasis", which we may here interpret as "sustainability")—the system must have suitable communication and control.

Diagnosis

The tie between information and action has been severed, Wiener too observed.

Our society's communication-and-control is broken, and it has to be restored.

To make that point, Wiener cited an earlier work, Vannevar Bush's 1945 article "As We May Think", where Bush urged the scientists to make the task of revising their own communication their next highest priority—the World War Two having just been won.

These calls to action remained, however, without effect. And it is not difficult to see why.

"As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved," observed David Bohm.

Wiener too entrusted his insight to the communication whose tie with action had been severed!

We have assembled a formidable collection of academic results that shared the same fate—to illustrate a general phenomenon we are calling Wiener's paradox.

It may be disheartening to our academic colleagues to see that so many best ideas of our best minds have remained ignored. But this sentiment will quickly be transformed to holotopian optimism, when we look at the vast creative frontier that is opening up; which Vannevar Bush pointed to already in 1945.

Optimism will turn into enthusiasm, when we also consider this commonly ignored fact:

</blockquote>The information technology we now commonly use to communicate with the world was created to enable a paradigm shift on that very frontier.</blockquote>

Vannevar Bush pointed to the need for new paradigm already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" really means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that—given the vast volumes of our information—our knowledge work must be organized in a way that enables us to benefit from each other's thinking. That technology and processes must be devised to enable us to in effect "connect the dots" or think together, as a single mind does. Bush described a prototype system called "memex", which was based on microfilm as technology.

Douglas Engelbart, however, took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected together into a network—then the overall result is that we are connected together as the cells in a human organism are connected by the nervous system.

The earlier innovations in this area—from clay tablets to the printing press—required that a physical object be transported; this new technology allows us to "create, integrate and apply knowledge" concurrently, as cells in a human nervous system do.

We can now develop insights and solutions together! We can have results instantly!

Engelbart's goal was to vastly improve our ability to deal with the "complexity times urgency" of our problems, which he saw as growing at an accelerated rate or "exponentially".

This three minute video clip, which we called "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", offers an opportunity for a pause. Imagine the effects of improving the planetary system (and its various subsystems) for "development, integration and application of knowledge". Imagine "the effects of getting 5% better", Engelbart commented with a smile. Then our old man put his fingers on his forehead, and looked up: "I've always imagined that the potential was... large..." The potential is not only large; it is staggering. The improvement that can and needs to be achieved is not only orders-of-magnitude large; it is qualitative— from a system that doesn't really work, to one that does.

To Engelbart's dismay, this new "collective nervous system" ended up being use to only make the old processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that broadcast information.

The above observation by Anthony Giddens points to the impact this had on culture; and on "human quality".

Dazzled by an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.

But ontological security is what binds us to power structure.

Remedy

What is to be done, if we should be able to use the new technology to change our collective mind?

Engelbart left us a clear answer in the opening slides of his "A Call to Action" presentation, which were prepared for a 2007 panel that Google organized to share his vision to the world, but were not shown(!).

In the first slide, Engelbart emphasized that "new thinking" or a "new paradigm" is needed. In the second, he pointed out what this "new thinking" was.

We ride a common economic-political vehicle traveling at an ever-accelerating pace through increasingly complex terrain.

Our headlights are much too dim and blurry. We have totally inadequate steering and braking controls.

There can be no doubt that systemic innovation was the direction Engelbart was pointing to. He indeed published an ingenious methodology for systemic innovation already in 1962, six years before Jantsch and others created theirs in Bellagio, Italy; and he used this methodology throughout his career.

Engelbart also made it clear what needs to be our next step—by which the spell of the Wiener's paradox is to be broken. He called it "bootstrapping"—and we adopted bootstrapping as one of our keywords. The point here is that only writing about what needs to be done (the tie between information and action being broken) will not lead to a desired effect; the way out of the paradox, or bootstrapping, means that we act—and either create a new system with our own minds and bodies, or actively help others do that.

What we are calling knowledge federation is the 'collective thinking' that the new informati9on technology enables, and our society requires.

The Knowledge Federation transdiscipline was created by an act of bootstrapping, to enable bootstrapping. Originally, we were a community of knowledge media researchers and developers, developing the collective mind solutions that the new technology enables. Already at our first meeting, in 2008, we realized that the technology that we and our colleagues were developing has the potential to change our collective mind; but that to realize that potential, we need to self-organize differently.

Ever since then have been bootstrapping, by developing prototypes with and for various communities and situations.

Among them, we highlight

- Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism, IEJ2011

- Tesla and the Nature of Creativity, TNC2015

- The LIghthouse 2016

The first, IEJ2011m, shows how researchers, journalists, citizens and creative media workers can collaborate to give the people exactly the kind of information they need—to be able to orient themselves in contemporary world, and handle its challenges correctly.

The second, TNC2015, shows how to federate a result of a single scientist—which is written in an inaccessible language, and has high potential relevance to other fields and to the society at large.

The third, The Lighthouse 2016, empowers a community of researchers (the concrete prototype was made for and with the International Society for the Systems Sciences) to federate a single core insight that the society needs from their field. (Here the concrete insight was that "the free competition" cannot replace "communication and control" and provide "homeostasis"—as Wiener already argued in Cybernetics, in 1948.)

Together, those three prototypes constitute a prototype solution to the Wiener's paradox.