Difference between revisions of "Holotopia"

m |

m |

||

| Line 1,144: | Line 1,144: | ||

<blockquote>Our core strategy is to <em>change</em> the institutional ecology that makes us small.</blockquote> | <blockquote>Our core strategy is to <em>change</em> the institutional ecology that makes us small.</blockquote> | ||

| − | <p>We will <em>not</em> sidestep that goal by adapting to the existing <em>order of things</em>, treating the development of <em>holotopia</em> as "our project" and trying to make it "successful" | + | <p>We will <em>not</em> sidestep that goal by adapting to the existing <em>order of things</em>, treating the development of <em>holotopia</em> as "our project" and trying to make it "successful"—within that very order of things we have undertaken to change.</p> |

<p>We insist on considering the development of the <em>holotopia</em> as <em>our generation</em>'s project. And we offer it to you as <em>your project</em> as much as ours. Our core strategy is to inspire and empower <em>you</em> to make a difference.</p> | <p>We insist on considering the development of the <em>holotopia</em> as <em>our generation</em>'s project. And we offer it to you as <em>your project</em> as much as ours. Our core strategy is to inspire and empower <em>you</em> to make a difference.</p> | ||

Revision as of 05:56, 19 October 2020

Contents

- 1 HOLOTOPIA

- 1.1 An Actionable Strategy

- 1.2 Imagine...

- 1.3 Our proposal

- 1.4 A proof of concept application

- 1.5 A vision

- 1.6 A principle

- 1.7 A method

- 1.8 Five insights

- 1.9 Scope

- 1.10 Power structure

- 1.11 Collective mind

- 1.12 Socialized reality

- 1.13 Narrow frame

- 1.14 Convenience paradox

- 1.15 Summary and conclusions

- 1.16 A strategy

- 1.17 We will not solve our problems

- 1.18 Large change is easy

- 1.19 We will not change the world

- 1.20 Tactical assets

- 1.21 The arts

- 1.22 Five insights

- 1.23 The elephant

- 1.24 Stories

- 1.25 The mirror

- 1.26 The dialog

- 1.27 Ten themes

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

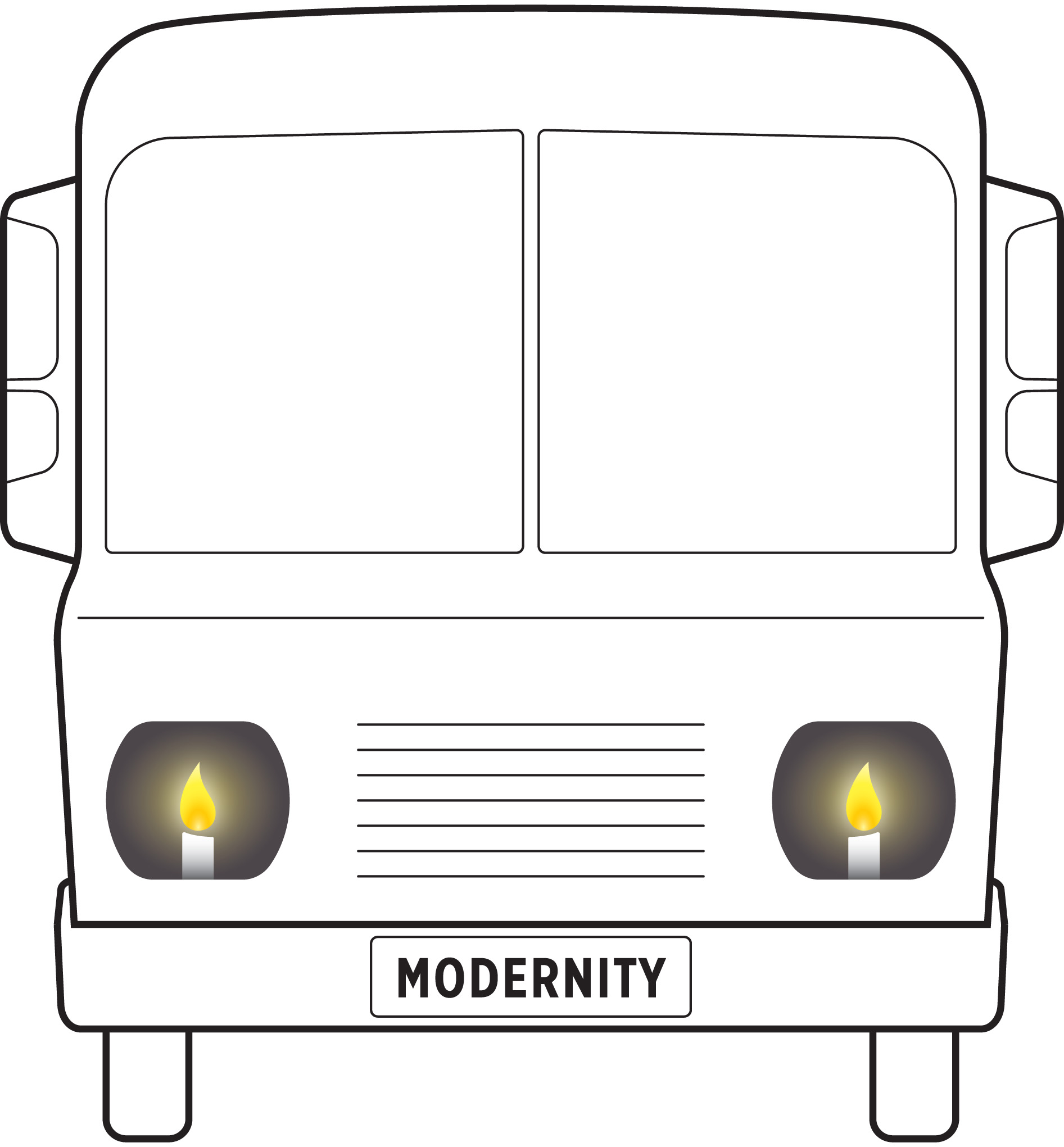

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Our proposal

The core of our knowledge federation proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of knowledge federation, where initial answers to relevant questions are proposed, and in part implemented in practice.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field, and a real-life praxis (informed practice).

Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a 'cardboard model of a city', and a 'construction site'. By sharing them we are not making a case for a specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life praxis.

A proof of concept application

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to "change course":

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

Is it really true that we must "change course"? While this question may seem compelling, our focus will be on a related practical task:

The purpose of the Holotopia project is to restore our ability to "change course".

The fact that we must be able to "change course", when the circumstances demand that, can hardly be disputed. The fact that now, forty years later, The Club of Rome's call to action is still ignored and not even disputed—shows that there is some urgent work that needs to be done.

A vision

We begin by providing a guiding vision.

Holotopia is a vision of a possible future that emerges when proper 'light' has been 'turned on'.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. In view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" emerged as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It is a more attractive vision of the future than what the common utopias offered—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not yet exist. And yet the holotopia is readily attainable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights, as explained below.

A principle

What do we need to do to "change course" toward holotopia?

The five insights point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by the holotopia's very name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

A method

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To be able to make things whole—we must be able to see things whole!

To highlight that the knowledge federation methodology described and implemented in the proposed prototype affords that very capability, to see things whole, in the context of the holotopia we refer to it by the pseudonym holoscope.

While the characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

To see things whole, we must look at all sides.

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for multiple ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. The scopes and the resulting views have similar meaning and role as projections do in technical drawing. The views that show the entire whole from a certain angle are called aspects.

This modernization of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed creation of the ways in which we look at a theme or issue—has become necessary in our situation, suggests the bus with candle headlights. But it also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not "reality pictures", contending for that status with one other and with our conventional ones.

In the holoscope, the legitimacy and the peaceful coexistence of multiple ways to look at a theme is axiomatic.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

A way of looking or scope—which reveals a structural problem, and helps us reach a correct assessment of an object of study or situation—is a new kind of result that is made possible by (the general-purpose science that is modeled by) the holoscope.

We will continue to use the conventional way of speaking and say that something is as stated, that X is Y—although it would be more accurate to say that X can or needs to be perceived (also) as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way (to use the offered scopes); and to do that collaboratively, in a dialog.

Five insights

Scope

What is wrong with our present "course"? In what ways does it need to be changed? What benefits will result?

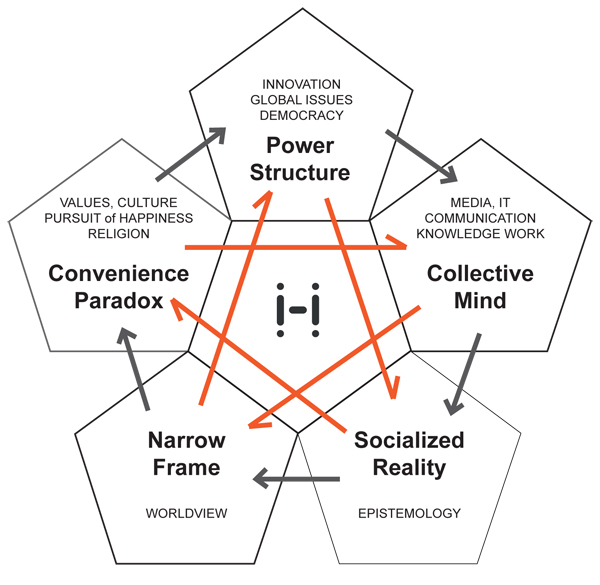

We apply the holoscope and illuminate five pivotal themes, which determine the "course":

- Innovation—the way we use our ability to create, and induce change

- Communication—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is handled

- Epistemology—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning; or "the relationship we have with information"

- Method—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life, or "the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it"

- Values—the way we "pursue happiness", which in the modern society directly determines the course

In each case, we see a structural defect, which led to perceived problems. We demonstrate practical ways, partly implemented as prototypes, in which those structural defects can be remedied. We see that their removal naturally leads to improvements that are well beyond the elimination of problems.

The holotopia vision results.

In the spirit of the holoscope, we here only summarize the five insights—and provide evidence and details separately.

Scope

What might constitute "a way to change course"?

"Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it", observed Peccei. Imagine if some malevolent entity, perhaps an insane dictator, took control over that power!

The power structure insight is that no dictator is needed.

While the nature of the power structure will become clear as we go along, imagine it, to begin with, as our institutions; or more accurately, as the systems in which we live and work (which we simply call systems).

Notice that systems have an immense power—over us, because we have to adapt to them to be able to live and work; and over our environment, because by organizing us and using us in certain specific ways, they decide what the effects of our work will be.

The power structure determines whether the effects of our efforts will be problems, or solutions.

Diagnosis

How suitable are the systems in which we live and work for their all-important role?

Evidence shows that the power structure wastes a lion's share of our resources. And that it either causes problems, or make us incapable of solving them.

The root cause of this malady is in the way systems evolve.

Survival of the fittest favors the systems that are predatory, not those that are useful.

This excerpt from Joel Bakan's documentary "The Corporation" (which Bakan as a law professor created to federate an insight he considered essential) explains how the most powerful institution on our planet evolved to be a perfect "externalizing machine" ("externalizing" means maximizing profits by letting someone else bear the costs, notably the people and the environment), just as the shark evolved to be a perfect predator. This scene from Sidney Pollack's 1969 film "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" will illustrate how the power structure affects our own condition.

The systems provide an ecology, which in the long run shapes our values and "human quality". They have the power to socialize us in ways that suit their needs. "The business of business is business"; if our business is to succeed in competition, we must act in ways that lead to that effect. Whether we bend and comply, or get replaced—will from the point of view of the system make no difference.

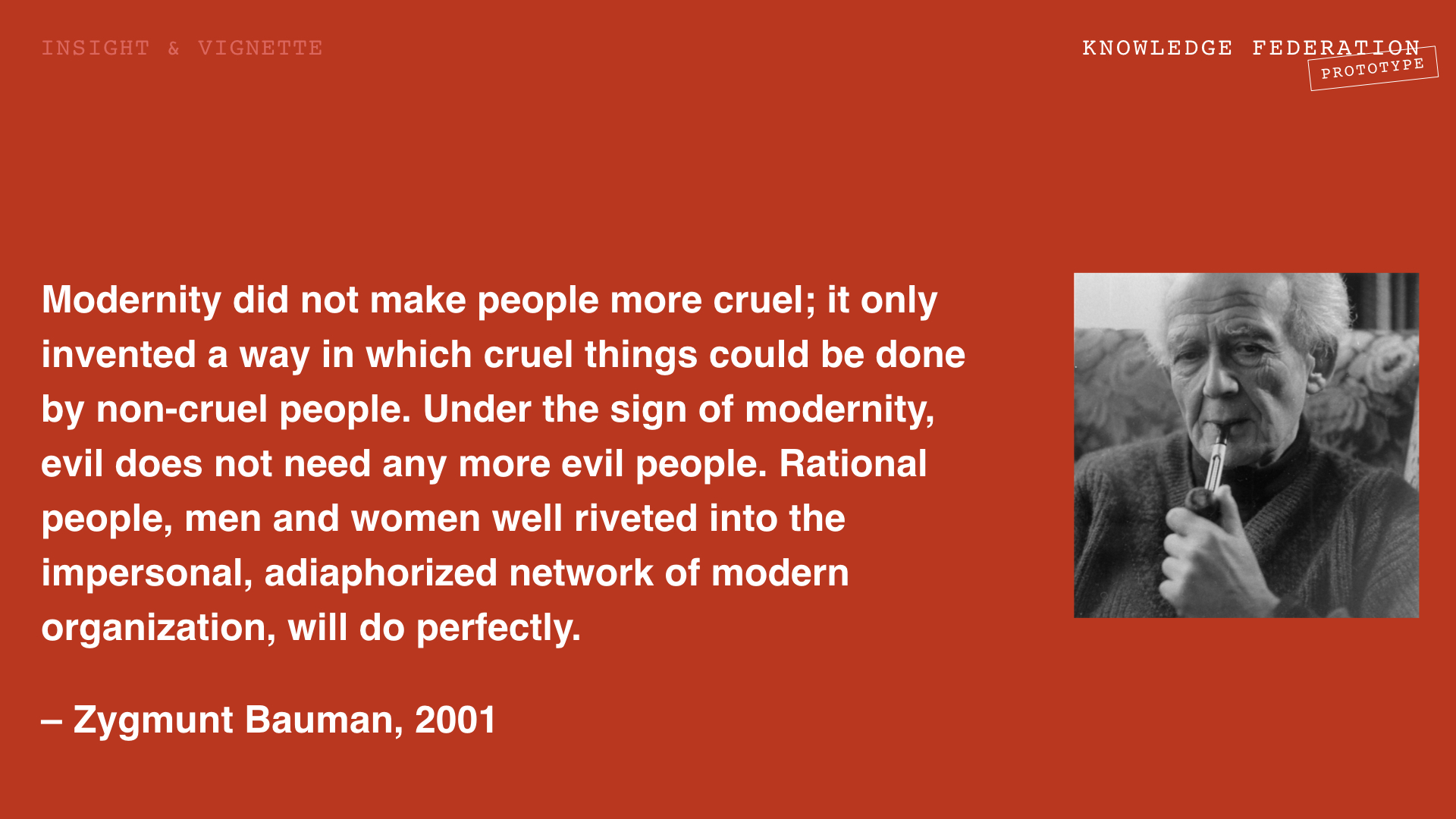

A consequence, Zygmunt Bauman diagnosed, is that bad intentions are no longer needed for bad things to happen. Through socialization, the power structure can co-opt our duty and commitment, and even heroism and honor.

Bauman's insight that even the holocaust was a consequence and a special case, however extreme, of the power structure, calls for careful contemplation: Even the concentration camp employees, Bauman argued, were only "doing their job"—in a system whose character and purpose was beyond their field of vision, and power to change.

While our focus is on the power structures of the past, we are committing—in all innocence, by acting only through the power structures we are part of—the greatest massive crime in human history.

Our children may not have a livable planet to live on.

Not because someone broke the rules—but because we follow them.

Remedy

The fact that we will not solve our problems unless we develop the capability to update our systems has not remained unnoticed.

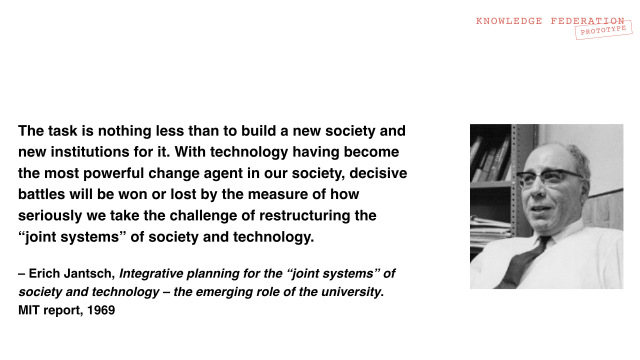

The very first step that the The Club of Rome's founders did after its inception, in 1968, was to convene a team of experts, in Bellagio, Italy, to develop a suitable methodology. They gave making things whole on the scale of socio-technical systems the name "systemic innovation"—and we adapted that as one of our keywords.

The work and the conclusions of this team were based on results in the systems sciences. In the year 2000, in "Guided Evolution of society", systems scientist Béla H. Bánáthy surveyed relevant research, and concluded in a true holotopian tone:

We are the first generation of our species that has the privilege, the opportunity and the burden of responsibility to engage in the process of our own evolution. We are indeed chosen people. We now have the knowledge available to us and we have the power of human and social potential that is required to initiate a new and historical social function: conscious evolution. But we can fulfill this function only if we develop evolutionary competence by evolutionary learning and acquire the will and determination to engage in conscious evolution. These two are core requirements, because what evolution did for us up to now we have to learn to do for ourselves by guiding our own evolution.

In 2010 Knowledge Federation began to self-organize to enable progress on this frontier.

The method we use is simple: We create a prototype of a system, and a transdisciplinary community and project around it to update it continuously. The insights in participating disciplines can in this way have real or systemic effects.

Our very first prototype of this kind, the Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism in 2011, was of a public informing that identifies systemic causes and proposes corresponding solutions (by involving academic and other experts) of perceived problems (reported by people directly, through citizen journalism).

A year later we created The Game-Changing Game as a generic way to change systems—and hence as a "practical way to craft the future"; and based on it The Club of Zagreb, as an update to The Club of Rome.

Each of about forty prototypes in our portfolio illustrates systemic innovation in a specific domain. Each of them is composed in terms of design patterns—problem-solution pairs, ready to be adapted for other applications and domains.

The Collaborology prototype, in education, will highlight some of the advantages of this approach.

An education that prepares us only for traditional professions, once in a lifetime, is an obvious obstacle to systemic change. Collaborology implements an education that is in every sense flexible (self-guided, life-long...), and in an emerging area of interest (collaborative knowledge work, as enabled by new technology). By being collaboratively created itself (Collaborology is created and taught by a network of international experts, and offered to learners world-wide), the economies of scale result that dramatically reduce effort. This in addition provides a sustainable business model for developing and disseminating up-to-date knowledge in any domain of interest. By conceiving the course as a design project, where everyone collaborates on co-creating the learning resources, the students get a chance to exercise their "human quality". This in addition gives the students an essential role in the resulting 'knowledge-work ecosystem' (as 'bacteria', extracting 'nutrients') .

Scope

We have just seen that our key evolutionary task is to make institutions whole.

Where—with what institution or system—shall we begin?

The handling of information, or metaphorically our society's 'headlights', suggests itself as the answer for several reasons.

One of them is obvious: If information and not competition will be our guide, then our information will need to be different.

In his 1948 seminal "Cybernetics", Norbert Wiener pointed to another reason: In social systems, communication—which turns a collection of independent individual into a coherently functioning entity— is in effect the system. It is the communication system that determines how the system as a whole will behave. Wiener made that point by talking about the colonies of ants and bees. Cybernetics has shown—as its main point, and title theme—that "the tie between information and action" has an all-important role, which determines (Wiener used the technical keyword "homeostasis", but let us here use this more contemporary one) the system's sustainability. The full title of Wiener's book was "Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine". To be able to correct their behavior and maintain inner and outer balance, to be able to "change course" when the circumstances demand that, to be able to continue living and adapting and evolving—a system must have suitable communication-and-control.

Diagnosis

Presently, our core systems, and with our civilization as a whole, do not have that.

The tie between information and action has been severed, Wiener too observed.

Our society's communication-and-control is broken; it needs to be restored.

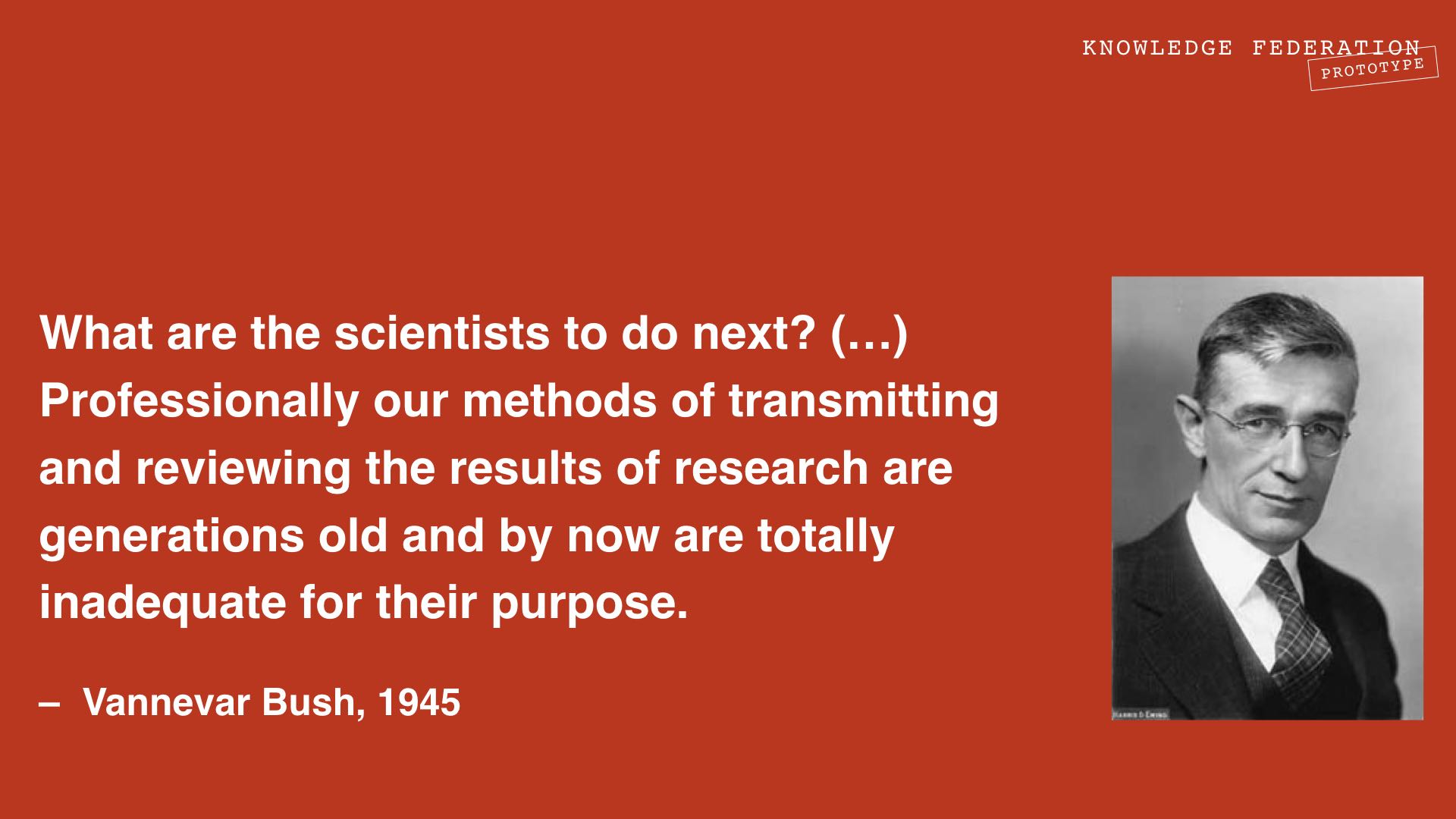

To make that point, Wiener cited an earlier work, Vannevar Bush's 1945 article "As We May Think", where Bush diagnosed that the tie between scientific information, and public awareness and policy, had been broken. Bush urged the scientists to make the task of revising their communication their next highest priority—the World War Two having just been won.

These calls to action remained without effect.

"As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved," observed David Bohm. Wiener too entrusted his insight to the communication whose tie with action had been severed. We have assembled a collection of examples of similarly important academic results that shared a similar fate—to illustrate a general phenomenon we called the Wiener's paradox.

As long as the link between communication and action is broken—the academic results that challenge the present "course" or point to a new one will tend to be ignored!

To an academic researcher, it may feel disheartening to see that so many best ideas of our best minds have been ignored. What's the point of all the hard work and publishing—when even the most basic insights from our field have not yet been communicated to the public? The insights that are needed for understanding the very purpose of our field—and hence the meaning and relevance of of all the nuances that we are presently working on?

This sentiment is, however, transformed to holotopian optimism, as soon we see 'the other side of the coin'—the vast creative frontier that is opening up. We are empowered to, we are indeed obliged to reinvent the systems in which we live and work, and our own, academic system to begin with—by reconfiguring the communication that holds each of them together; and enables them to interoperate.

And optimism will turn into enthusiasm, when we consider also this widely ignored fact:

The core elements of the information technology we now use to communicate were created to enable the developments and breakthroughs on that very frontier.

The 'lightbulb' has already been created—and for the purpose of giving our society the vision it needs.

But we are still holding on to our 'candles'!

Vannevar Bush pointed to the need for this new frontier already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that given our vast volumes of information—technology and processes must be devised to enable us to "connect the dots" or think together, as a single mind does. He described a prototype system called "memex", based on microfilm as technology.

Douglas Engelbart took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected together into a network—then the overall result is that we are connected together as the cells in a human organism are connected by the nervous system.

All earlier innovations in this area—from the clay tablets to the printing press—required that a physical medium with the message be physically transported.

This new technology allows us to "create, integrate and apply knowledge" concurrently, as cells in the human organism do.

We can develop insights and solutions together.

We can become "collectively intelligent".

Engelbart conceived this new technology as a key step toward enabling us (or more precisely our systems) to tackle the "complexity times urgency" of our problems, which he saw as growing at an accelerated rate.

But this, Engelbart observed, requires "new thinking": It requires that we use the technology to make our systems whole.

This three minute video clip, which we called "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", will give us a chance to pause and reflect, and see what all this practically means. Think about the prospects of improving our institutional and civilizational collective minds. Imagine "the effects of getting 5% better", Engelbart commented with a smile. Then he put his fingers on his forehead and looked up: "I've always imagined that the potential was... large..." The improvement that is both necessary and possible is not just stupendously large; it is qualitative—from communication that doesn't work, and systems that don't work, to ones that do.

To Engelbart's dismay, our new "collective nervous system" ended up being used to do no better than make the old processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that broadcast data, and overwhelm us with information.

This observation by Anthony Giddens points to the effects that our dazzled and confused collective mind had on our culture; and on "human quality".

Our sense of meaning having been drowned in an overload of data, in a reality whose complexity is well beyond our comprehension—we have no other recourse but "ontological security". We find a sense of meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it a competitively.

But that is exactly what binds us to power structure!

Remedy

How can we repair the severed tie between communication and action?

How can we change our collective mind—as our situation demands, and our technology enables?

Engelbart left us a simple and clear answer: Bootstrapping.

His point was that only writing about what needs to be done would not have the intended effect (the tie between information and action being broken). Bootstrapping means that we consider ourselves as parts in our systems; and that we self-organize, and act as it may best serve to restore them to wholeness.

Bootstrapping means that we either create new systems with the material of our own minds and bodies, or help others do that.

The Knowledge Federation transdiscipline was conceived by an act of bootstrapping, to enable bootstrapping.

What we are calling knowledge federation is an umbrella term for a variety of activities and social processes that together comprise a well-functioning collective mind. Their development and dissemination obviously requires a new body of knowledge, and a new institution.

The critical task is, however, to bootstrap—i.e. to self-organize so as to enable the state of the art knowledge and technology to be woven directly into systems.

Paddy Coulter, Mei Lin Fung and David Price speaking at our "An Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism" workshop in Barcelona

We use the above triplet of photos ideographically, to highlight that we are doing that.

In 2008, when Knowledge Federation had its inaugural meeting, two closely related initiatives were formed: Program for the Future (a Silicon Valley-based initiative to continue and complete "Doug Engelbart's unfinished revolution") and Global Sensemaking (an international community of researchers and developers, working on technology and processes for collective sense making). The featured participants of our 2011 workshop in Barcelona, where our public informing prototype was created, are Paddy Coulter (the Director of Oxford Global Media and Fellow of Green College Oxford, formerly the Director of Oxford University's Reuter Program in Journalism) Mei Lin Fung (the founder of Program for the Future) and David Price (who co-founded both the Global Sensemaking R & D community, and Debategraph—which is now the leading global platform for collective thinking).

Other prototypes contributed other design patterns for restoring the severed tie between information and action. The Tesla and the Nature of Creativity TNC2015 prototype showed how to federate a research result that has general interest for the public, which is written in an academic vernacular (of quantum physics). The first phase of this prototype, where the author collaborated with our communication design team, turned the academic article into a multimedia object, with intuitive, metaphorical diagrams and explanatory interviews with the author. The second phase was a high-profile live streamed dialog, where the result was announced and discussed. The third phase was online collective thinking about the result, by using Debategraph.

The Lighthouse 2016 prototype is conceived as a direct remedy for the Wiener's paradox, created for and with the International Society for the Systems Sciences. This prototype models a system by which an academic community can federate an answer to a socially relevant question (combine their resources in making it reliable and clear, and communicate it to the public).

The question in this case was whether can rely on "free competition" to guide the evolution and the operation of our systems; or whether the alternative—the information developed in the systems sciences—should be used.

Scope

"Act like as if you loved your children above all else",Greta Thunberg, representing her generation, told the political leaders at Davos. Of course political leaders love their children—don't we all? But Greta was asking them to 'hit the brakes'; and when the 'bus' they are believed to be 'driving' is inspected, it becomes clear that its 'brakes' too are dysfunctional.

The job of political leaders is to keep 'the bus on course' (the economy growing) for yet another four-year term. Changing 'course', by changing the system, is beyond what they are able to do, or even imagine doing.

The COVID-19 pandemic may demand systemic changes now.

Who—what institution or system—will lead us through our unprecedentedly large creative challenges?

Both Erich Jantsch and Doug Engelbart believed "the university" would have to be the answer; and they made their appeals accordingly. But the universities ignored them.

Why?

There are evidently two ways in which the role of the university in our society can be conceived of: The role that the university must fulfill (claim the new-paradigm thinkers), if our civilization is to resolve its problems and live; and the role that the academic professionals consider themselves to be in.

We shall see that this dichotomy has roots in the way in which the university institution historically developed. And that the key to resolving it, and restoring the university to its all-important contemporary social role, is in the historicity of the academic values and procedures—which Stephan Toulmin pointed to in "Return to Reason"; and we summarized and commented in this blog post.

We have now come to the heart of our matter—the relationship we have with information.

We are about to see why changing the relationship we have with information is mandated on both fundamental and pragmatic grounds.

And why that is "a way to change course"—toward "a great cultural revival", and "a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world".

Diagnosis

This diagnosis will be an assessment of the contemporary academic condition and its causes.

We will come to understand this condition as a consequence of three developments or events in this institution's evolution. The first two will allow us to understand the origins of contemporary academic self-perception; the third one to see why this self-perception needs to change.

The first event was the university institution's point of inception, within the antique philosophical tradition; and concretely as Plato's Academy. John Marenbon described the mindset of the Academy as follows (in "Early Medieval Philosophy"; the boldface emphasis is ours):

Plato is justly regarded as a philosopher (and the earliest one whose works survive in quantity) because his method, for the most part, was to proceed to his conclusions by rational argument based on premises self-evident from observation, experience and thought. For him, it was the mark of a philosopher to move from the particular to the general, from the perceptions of the senses to the abstract knowledge of the mind. Where the ordinary man would be content, for instance, to observe instances of virtue, the philosopher asks himself about the nature of virtue-in-itself, by which all those instances are virtuous. Plato did not develop a single, coherent theory about universals (for example, Virtue, Man, the Good, as opposed to an instance of virtue, a particular man, a particular good thing); but the Ideas, as he called universals, play a fundamental part in most of his thought and, through all his different treatments of them, one tendency remaiuns constant. The Ideas are considered to exist in reality; and the particular things which can be perceived by the senses are held to depend, in some way, on the Ideas for being what they are. One of the reasons why Plato came to this conclusion and attached so much importance to it lies in a preconception which he inherited from his predecessors. Whatever really is, they argued, must be changeless; otherwise it is not something, but is always becoming something else. All the objects which are perceived by the senses can be shown to be capable of change: what, then, really is? Plato could answer confidently that the Ideas were unchanging and unchangeable, and so really were. Consequently, they—and not the world of changing particulars—were the object of true knowledge. The philosopher, by his ascent from the particular to the general, discovers not facts about the objects perceptible to the senses, but a new world of true, changeless being.

Any rational method must ultimately rest on premises or axioms that are not rationally proven, which are considered "self-evident from observation, experience and thought". An axiom here was that the purpose of the pursuit of knowledge is to know "reality". The only question, then, was How that was to be achieved.

The highlights we made in Marenbon's text allow us to formulate the first point of this diagnosis:

The university has its roots in a philosophical tradition whose goal was to pursue "true knowledge"—which was assumed to be the knowledge of unchanging and unchangeable "reality".

The second point is well known. We, however, honor its importance by illustrating it, however briefly, by revisiting our lead historical metaphor, "Galilei in house arrest" (we continue to use people stories as parables).

It was Aristotle, Plato's star student, who applied the Academia's rational method to a variety of themes. The recovery of Aristotle was a milestone in the intellectual history of the Middle Ages; but the Scholastics used his method to argue the truth of the Scripture.

Aristotle's physics was common sense: Objects tend to fall down; heavier objects tend to fall faster. Galilei proved him wrong by throwing stones of varying sizes from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. He devised a mathematical formula, by which the speed of a falling object could be calculated exactly. To the human mind about to become modern, Galilei (and the forefathers of science he here represents) demonstrated the superiority of the scientific way to truth.

We may now interpret these Toulmin's observations as follows: How could the rational method of Galilei and Newton, conceived for exploring exploring cosmology—which "had no day-to-day relevance to human welfare"—assume such an all-important role, become the foundation and the model for our pursuit of knowledge in general?

At that time, the Church and the tradition had the prerogative of determining how the people should live and behave, and what they should believe in. And as the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest might suggest—they held onto that prerogative most firmly! The scientists were allowed to pursue their interests only when they "had no relevance to human welfare". But the basic axiom—that the goal of the pursuit of knowledge was to know the unchanging and unchangeable "reality"—was still taken for granted. So when the scientists demonstrated the ability to substitute mathematical formulas and experiments for the "earlier theological accounts of Nature"—that their way was the right way seemed obvious.

During the Enlightenment, science replaced the Bible and the tradition, and the classical philosophy, in the role of our society's trusted way to knowledge.

The above two events allow us to understand the self-conception of the academic professionals, the way they understand their social role: The university's traditional role is not to pursue practical knowledge, but the knowledge of knowledge or epistemology—based on which all knowledge is to be pursued.

This self-image is reflected in the structure of the traditional European university, which included only those fields on which practical knowledge was believed to be founded—such as philosophy, mathematics and physics. The more practical fields, such as architecture and design, were relegated to "professional schools".

Coming now to our third event, and the reasons why this academic self-conception needs to change, we observe that correcting the pursuit of knowledge, by keeping it in sync with knowledge of knowledge, is what the academic tradition has been about since its inception: Wasn't that what Socrates was doing when he engaged his contemporaries in dialogues?

The third event is that the fundamental axiom—that science is the way to know the "reality"—has been invalidated by the results of the 20th century science and philosophy.

While we federated this fact carefully, to see it, it is sufficient to read Einstein. (In our condensed or high-level manner of speaking, Einstein has the role of the icon of "modern science". Quoting Einstein is our way to say "here is what modern science has been telling us".)

It is simply impossible, Einstein remarked (while writing about "Evolution of Physics" with Leopold Infeld), to open up the 'mechanism of nature' and verify that our ideas and models correspond to the real thing. We cannot even conceive of such a comparison! Science is not the way to know "reality". According to Einstein, “Science is the attempt to make the chaotic diversity of our sense-experience correspond to a logically uniform system of thought".

The results in the 20th century science and philosophy demand that we see the very idea of "reality" in a completely new way—not as something we discover, but as something we construct.

What we call "reality" is a result of a complex interplay between cognitive and social processes.

In "Social Construction of Reality", Berger and Luckmann described the social process by which "reality" is constructed. They pointed to the role that a certain specific kind of reality construction called "universal theories" (theories about the nature of reality, which determine how truth and meaning are to be created) played in maintaining the given social and political order of things. An example of a "universal theory" is the Biblical worldview of Galilei's prosecutors. By ordaining the kings, the Church made it clear to everyone that their absolute power was legitimately delegated from the Almighty Himself.

Other results allow us to understand more deeply the nature of "social reality construction", or socialization; and its relationship with renegade power.

We condensed them to the Odin–Bourdieu–Damasio thread (the thread is an adaptation of Vannevar Bush's technical idea for organizing the collective mindwork, which he called "trail"). Since we offered an outline of this thread separately, we here only highlight only those points that are necessary for reaching the socialized reality insight.

Through the metaphor of the turf behavior of horses, the Odin the Horse vignette points to an instinctive drive that we humans also share—to dominate and control; and to expand our 'turf'—whatever it may be.

The second vignette is about Pierre Bourdieu's experiences in Algeria, and his "theory of practice" those experiences led him to. Bourdieu's "theory of practice" allows us to understand the intrinsic nature of the human turf behavior; how it creates renegade power, and our conception of "reality".

Bourdieu's theory allows us to understand how 'turf strife' can happen without anyone's intention, or even awareness.

Bourdieu used two keywords—"field" and "game"—to refer to the symbolic or cultural 'turf'. By calling it a field, he suggested something akin to a magnetic field, which orients our seemingly random or free behavior, without us noticing. By calling it a game, he portrayed it as something that structures or "gamifies" our social existence, by giving each of us certain set of "action capabilities", which Bourdieu called "habitus", in accordance with our social role. "The boss" has a certain body language and tone of voice; and so does "his secretary". The habitus, according to Bourdieu, tend to be transmitted from body to body directly. Everyone kneels down when the king enters the room; and naturally, we do too.

Bourdieu used the keyword "doxa" to point to the "reality" that results from such socialization; and to the common experience—that the social order of things we have been socialized to accept as "reality" is as immutable and as real as the physical reality we are living in.

The third vignette, whose lead protagonist is the cognitive neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, completes this thread by explaining why this pre-conscious body-to-body socialized reality holds us in such a strong cognitive grip. Damasio showed that our rational decision making, and are consciously maintained reality picture in general, are controlled by an embodied cognitive filter, which determines what options are rationally considered.

Damasio's research allows us to understand why we civilized humans don't rationally consider taking off our clothes and walking out in the street naked; and why we don't consider changing the systems in which we live and work.

We are now ready to condense these cognitive or epistemological insights to a single point.

The relationship we have with information is a result of a historical epistemological error.

This fundamental error has been detected and reported, but it has not been corrected.

Its practical consequences include:

- Stringent limits to creativity. A vast global army of selected, trained and publicly sponsored creative men and women are obliged to confine their work to only observing the world—by looking at it through the eye lenses of traditional disciplines.

- Severed tie between information and action. The perceived purpose of information being to complete the 'reality puzzle'—every new "piece of information" appears to be just as relevant as any other; and also necessary for completing the 'puzzle'. In the sciences and in the media, enormous amounts of information are produced "disconnected from usefulness"—as Postman diagnosed.

- Reification of institutions. Our "science", "democracy", "public informing" and other institutions have no explicitly stated purposes, against which their implementations may be measured; they simply are their implementations. It is for this reason that we use 'candles as headlights'.

- Destruction of culture. To see it, join us on an imaginary visit to a cathedral: There is awe-inspiring architecture; Michelangelo's Pietà meets the eye, and his frescos are near by. Allegri's Miserere is reaching us from above. And then there is the ritual. This, and a lot more, comprises the human-made 'ecosystem' called "culture", where the "human quality" grows. The myths of old, including the myth that "truth" means "correspondence with reality", were mere means by which the cultural traditions pursued this all-important end. We discarded this 'ecosystem' because we discredited its "reality picture". But "reality" is not—and it has never been—what the culture is about. The 'cultural species' are rapidly going extinct. And there we don't even have 'the temperature and the CO2 measurements', to diagnose problems and propose policies.

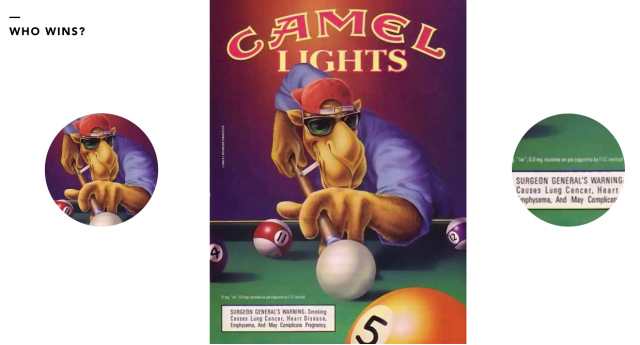

- Culture abandoned to power structure. It is sufficient to to look around: Advertising is everywhere. And explicit advertising is only a tip of an iceberg. Variuos kinds of "symbolic power" socialize us to be unaware consumers, and more generally to conform to power structure. Scientific techniques are being used; the story of Edward Bernays (Freud's American nephew who became "the pioneer of modern public relations and propaganda") is iconic.

The following conclusion suggests itself:

The Enlightenment did not liberate us from power-related reality construction.

Our socialization only changed hands—from the kings and the clergy, to the corporations and the media.

It may seem preposterous to claim that the contemporary 'Galilei' (the ideas that point to a new evolutionary "course") is held in 'house arrest' by the very institution that was created to continue his legacy. But not when the nature of "symbolic power" is understood.

Not when we acknowledge that the university, and not the Church, is now in charge of the "universal theory".

Remedy

An organism incapable of adapting to it situation, and of evolving so as to restore that capability, is scheduled for extinction. So is a civilization.

The power to restore the severed tie between information and action is in academia's hands. But the academia's tie with information and action too is severed! Having evolved as a way to pursue "unchanging and unchangeable true knowledge", the academia has no systemic provisions for changing the way it pursues knowledge; for evolving as the environmental conditions demand.

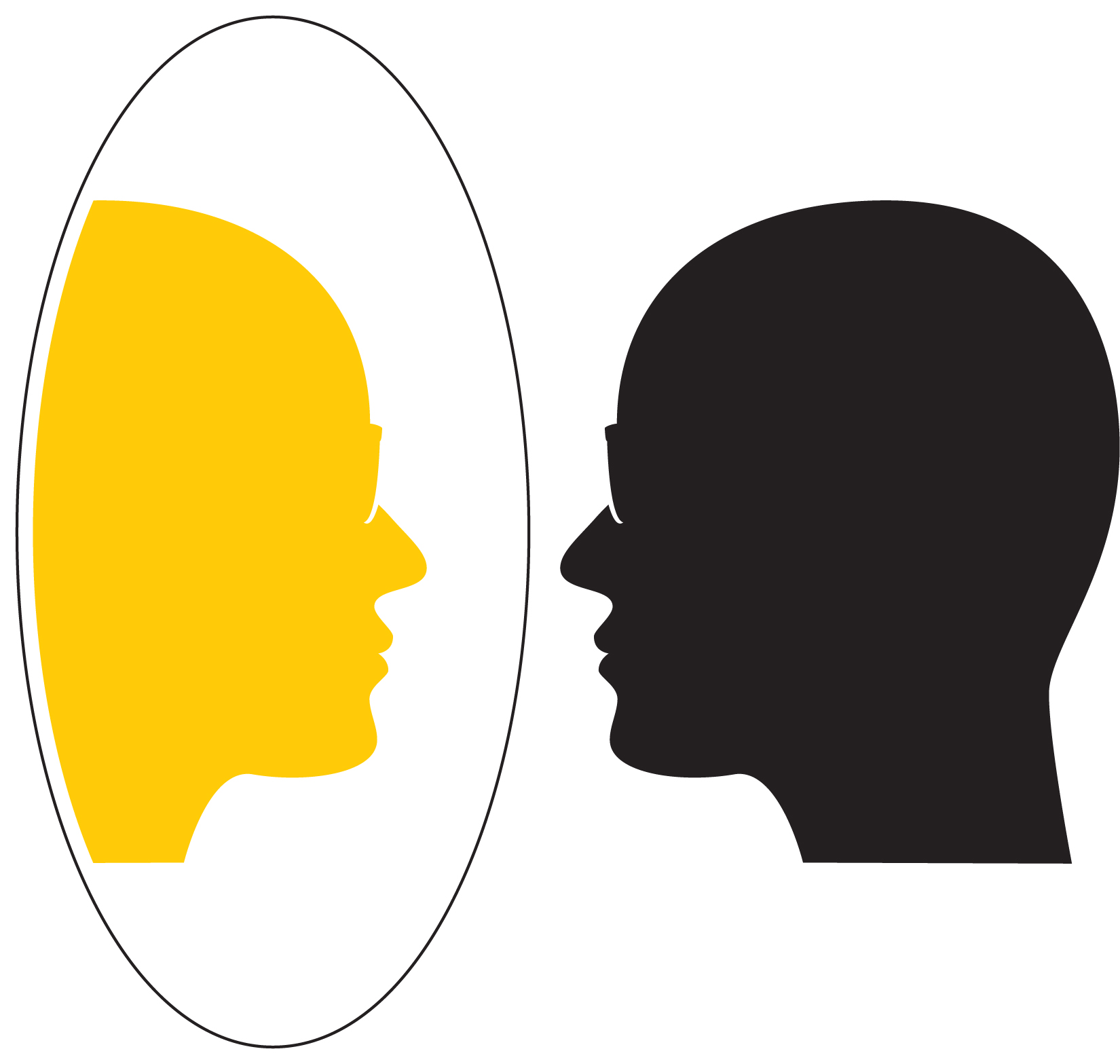

The key is to return to academia's original ethos and activity, the Socratic dialogue. In the spirit of the holoscope, we characterized the academia's contemporary situation by a metaphorical image, the Mirror ideogram—which points to the way in which that situation needs to be handled.

The mirror reflects two large changes in the determinants of the academic profession, which developed after its institutionalization acquired its present form. When we look at a mirror, we see ourselves in the world. We see that we are not above the world, looking at it "objectively".

The world we see ourselves in is a world in dire need for creative action. We see that we have the key role in that world.

The mirror urges us to abolish reification, and restore accountability.

How can we do that, without sacrificing the core values of our tradition—academic rigor; and academic freedom?

The message of the mirror is that we can, and must, restore both accountability and rigor and freedom. That seemingly impossible or 'magical' solution is symbolized by the metaphor of stepping through the mirror.

By walking through the mirror, we can both increase freedom and rigor—and step into our new role!

What makes this possible is what Villard Van Orman Quine called "truth by convention"—and we adapted as one of our keywords.

Quine opened "Truth by Convention" by observing:

"The less a science has advanced, the more its terminology tends to rest on an uncritical assumption of mutual understanding. With increase of rigor this basis is replaced piecemeal by the introduction of definitions. The interrelationships recruited for these definitions gain the status of analytic principles; what was once regarded as a theory about the world becomes reconstrued as a convention of language. Thus it is that some flow from the theoretical to the conventional is an adjunct of progress in the logical foundations of any science."

If truth by convention has been the way in which the sciences improve their logical foundations—why not use it to update the logical foundations of knowledge work at large?

Truth by convention is common in mathematics: "Let X be Y. Then..." and the argument follows. Insisting that X "really is" Y is obviously meaningless. A convention is valid only within a given context—which may be an article, or a theory, or a methodology.

Truth by convention allows science to expand into its new and larger role.

Truth by convention allow for a new kind of rigor—where our work with information is liberated from reification and other unstated assumptions.

It is also a way to turn the foundation on which we create truth and meaning, and the very "relationship we have with information", into a prototype—and allow them to evolve. Simply, we turn the state-of-the-art epistemological insights into a convention; and we change that convention when new insights or new social purposes make it obsolete.

Truth by convention does not require consensus, or changes in the traditional sciences.

We defined design epistemology by rendering the core of our proposal as a convention.

In the "Design Epistemology" research article (published in the special issue of the Information Journal titled "Information: Its Different Modes and Its Relation to Meaning", edited by Robert K. Logan; see this blog highlight with a link to the article) where we articulated this proposal, we made it clear that the design epistemology is only one of the many ways to implement this approach. We drafted a parallel between the modernization of science that can result in this way and the advent of modern art: By defining an epistemology and a methodology by convention, we can do in the sciences as the artists did, when they liberated themselves from the demand to mirror reality, by emulating the technique of Old Masters.

As the founders of science did, and as the contemporary artists do—on the other side of the mirror we can create the ways in which we practice our profession.

Our main two prototypes, the holoscope and the holotopia, model the academic and the social reality on the other side of the mirror.

Two concrete examples—our definitions of design and of visual literacy—will illustrate some of the advantages of using truth by convention to found academic work. Each of them is an example of substituting truth by convention for reification in an already existing academic field—and thereby giving the existing praxis an explicitly stated and up-to-date direction and purpose. The fact that those proposals were welcomed by the target communities suggests that this line of work may not need a new paradigm to become practical.

The example of design illustrates how the approach we are proposing can be used to provide both a rigorous academic foundation and a timely new direction to an academic field (this chronological summary provides links for in-depth exploration).

The definition of "design" gives us also a way to understand our contemporary situation, and our proposal.

We defined design as "the alternative to tradition", where design and tradition are (by convention) two alternative ways to wholeness. Tradition relies on spontaneous and incremental Darwinian-style evolution. Change is resisted; small changes are tested and assimilated through generations of use. We practice design when we consider ourselves accountable for wholeness.

Design must be used when tradition cannot be relied on.

Design must be in place when the rate change is too fast; or when the traditional order of things is no longer respected and maintained.

The situation we are in, which we pointed to by the bus with candle headlights metaphor, can now be understood as a result of a transition: We are no longer traditional; and we are not yet designing. Our call to action can now be understood as a call to complete modernization—and continue to evolve in a new way.

Reification can now be understood as the foundation that suits tradition; truth by convention suits design.

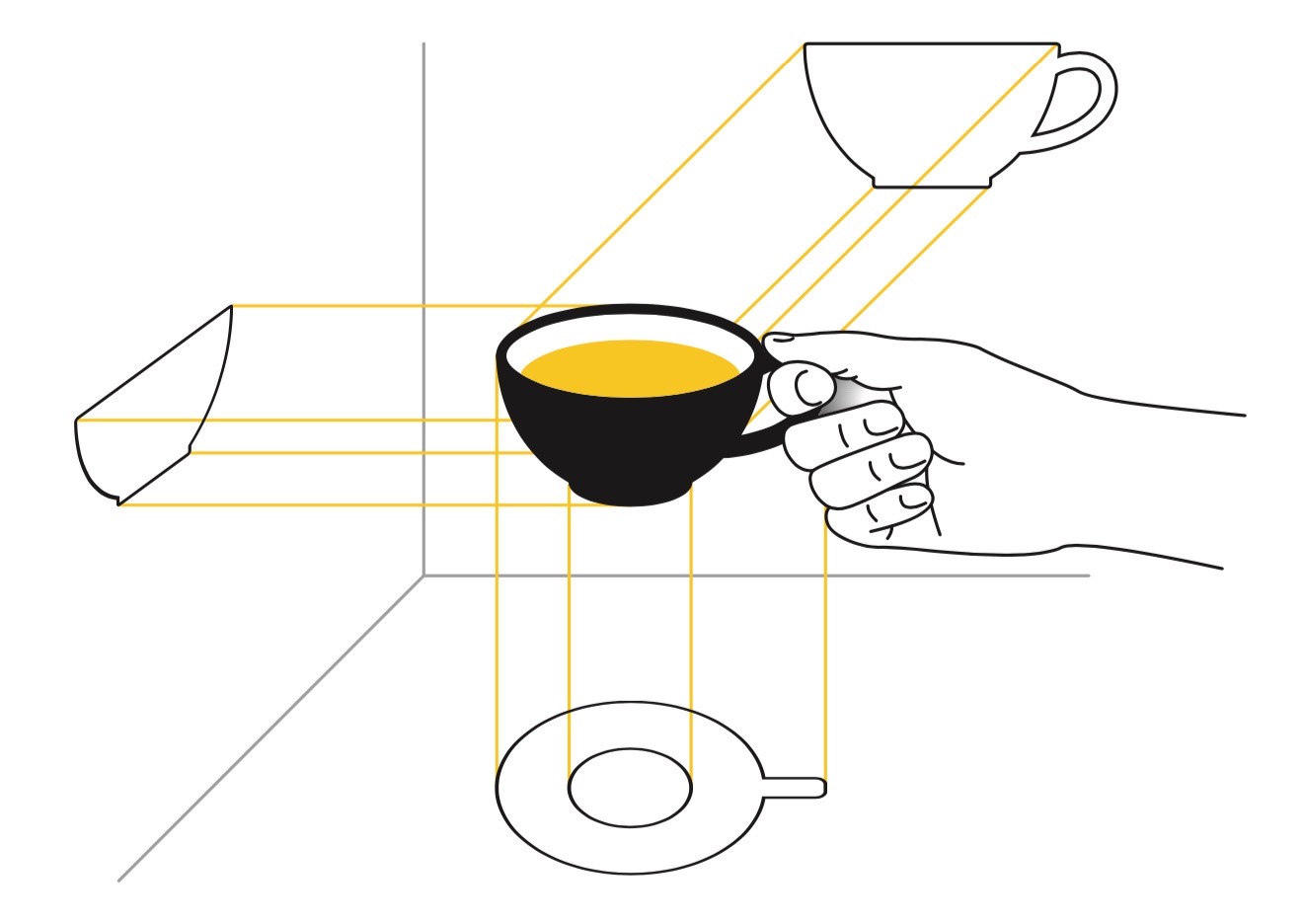

The second example: Our definition of implicit information, and of visual literacy as "literacy associated with implicit information, for the International Visual Literacy Association, was in spirit similar—but its point was different (see this summary).

We showed the above ideogram to highlight that again and again, on our contemporary-cultural scene, two kinds of information meet each other in a direct duel: The explicit information, represented by the explicit, factual and verbal warning in a black-and-white rectangle, and the implicit information, represented by the colorful and "cool" rest. The implicit information wins "hands down", this ideogram shows (or else this would not be a cigarette advertising). Our larger point was that while legislation, ethical sensibilities and "official" culture are focused on explicit information, our culture is dominated and created by implicit information.

We need visual literacy—to

- understand our heritage

- understand how subtle messages affect us

- be able to create implicit information—and redeem culture from power structure

Scope

We have just seen that the academic tradition—instituted as the modern university—finds itself in a much larger and more central social role than it was originally conceived for. We look up to the academia, and not to the Church and the tradition, for answers to the pivotal question:

How should we look at the world, to be able to comprehend and handle it?

That role, and that question, carry an immense power!

It was by providing a completely new answer to that question, that the last "great cultural revival" came about.

Diagnosis

So how should we look at the world, to be able to comprehend and handle it?

Nobody knows!

Of course, countess books and articles have been written about this theme since antiquity. But in spite of that—or should we say because of that—no consensus has emerged.

Since nobody felt accountable for supplying it, the way we the people look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it, shaped itself spontaneously—from odds and ends of science as they appeared to the public around the middle of the 19th century, when Darwin and Newton as cultural heroes were replacing Adam and Moses. What is today popularly considered as the "scientific worldview" took shape then—and remained largely unchanged.

As members of the homo sapiens species, this worldview would make us believe, we have the evolutionary privilege to be able to comprehend the world in causal terms, and make rational choices. Give us a correct model of the world, and we'll know exactly how to satisfy our needs (which we also know, because we can experience them directly). But the traditional cultures got it all wrong: Having been unable to explain the natural phenomena, they put a "ghost in the machine", and made us pray to him to give us what we needed. Science corrected that error—and now we can satisfy our needs by manipulating the mechanisms of nature directly, with the help of technology.

It is this causal or "scientific" understanding of the world that made us modern. Isn't that how we understood that women cannot fly on broomsticks?

While it is undoubtedly correct that the 19th century "scientific" worldview enabled us to wash away a wonderful amount of prejudice—it is also true that we have thrown out the 'baby' (culture) with the bath water.

From our collection of reasons why this way of looking at the world is obsolete and needs to be changed, we here mention only two.

The first reason is that the nature is not a mechanism.

The mechanistic way of looking at the world that Newton and his contemporaries developed in physics, which around the 19th century shaped the worldview of the masses, was later disproved and disowned by modern science. Research in physics showed that even the physical phenomena exhibit the kinds of interdependence that cannot be understood in "classical" or causal terms.

In "Physics and Philosophy", Werner Heisenberg, one of the progenitors of this research, described how "the narrow and rigid" way of looking at the world that our ancestors adapted from the 19th century science damaged culture—and in particular its parts on on which the "human quality" depended, such as ethics and religion. And how as a result the "instrumental" or (as Bauman called them) "adiaphorized" thinking and values became prominent. As we have seen, it is those values that bind us together into wasteful and destructive power structures.

Hear Heisenberg say that he expected that in the long run the philosophical and cultural consequences of atomic physics—the change of how we see everyday problems, and of culture—would be more important than the technical ones.

Heisenberg believed that the most valuable gift of modern physics to humanity would not be nuclear energy or semiconductor technology—but a cultural change, which would result from the dissolution of the rigid frame.

The theme we are touching upon is more than the relationship we have with information; what we are talking about determines the relationship we have with the world, and with each other. A suitable context for understanding its broader import is what Erich Jantsch called the "evolutionary paradigm". Jantsch explained the evolutionary paradigm via the metaphor of a boat in a river, representing a system (which may at the limit be the natural world, or our civilization). When we use the classical scientific paradigm, we position ourselves above the boat, and aim to look at it "objectively". The classical systems paradigm would position us on the boat, and we would seek ways to steer the boat effectively and safely. But when we use the evolutionary paradigm, we perceive ourselves as—water. We are evolution.

The narrow frame determines the way we are as 'water'—and hence our evolutionary "course", and our future.

In 2005, Hans-Peter Dürr (considered in Germany as Heisenberg's scientific "heir") co-wrote the Potsdam Manifesto, whose subtitle and message read "We need to learn to think in a new way". The reasons offered include scientific epistemological insights, and the global condition. The proposed new thinking is closely similar to the one that defines holotopia:

"The materialistic-mechanistic worldview of classical physics, with its rigid ideas and reductive way of thinking, became the supposedly scientifically legitimated ideology for vast areas of scientific and political-strategic thinking. (...) We need to reach a fundamentally new way of thinking and a more comprehensive understanding of our Wirklichkeit ["reality", or what we consider as "true"], in which we, too, see ourselves as a thread in the fabric of life, without sacrificing anything of our special human qualities. This makes it possible to recognize humanity in fundamental commonality with the rest of nature (...)"

The second reason is that even complex mechanisms ("classical" nonlinear dynamic systems) cannot be understood in causal terms.

It has been said that the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. Research in cybernetics explained this scientifically: The "hell" (which you may imagine as global issues, or the 'destination' toward which the 'bus' we are riding in is reportedly headed) tends to be a "side effect" of our best efforts and "solutions", reaching us through "nonlinearities" and "feedback loops" in the natural and social complex systems we are part of.

Hear Mary Catherine Bateson (cultural anthropologist and cybernetician, daughter of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson who pioneered both fields) say:

"The problem with Cybernetics is that it is not an academic discipline that belongs in a department. It is an attempt to correct an erroneous way of looking at the world, and at knowledge in general. (...) Universities do not have departments of epistemological therapy!"

Remedy

Truth by convention allows us to explicitly define and academically develop new ways to look at the world.

We called the result a methodology, and our prototype the Polyscopic Modeling methodology or polyscopy.

Polyscopy is a general-purpose methodology; it provides methods for creating insights about any chosen theme—on any level of generality.

Since the main purpose of the Polyscopic Modeling prototype is to point to the advantages of the methodological approach to general knowledge compared to both the narrow frame and the disciplinary approach, we here outline several of its design patterns.

- Polyscopy is a general-purpose methodology. As Abraham Maslow observed, to a person with a hammer in his hand everything looks like a nail. A scientific discipline is a 'hammer'. By virtue of being general-purpose, polyscopy allows for turning the traditional-academic approach to knowledge and to the world inside-out: Instead of having a fixed set of concepts and a method, and applying them where they can be applied (and thus sacrificing purpose to "objectivity")—we provide completely flexible concepts and methods, to be applied wherever reliable information is needed (while continuing to improve the methods). Polyscopy demands that we choose themes and ways of looking according to relevance; and that we create the corresponding information as well as we can. According to sociologists, we live in a post-traditional culture (where we no longer follow in the footsteps of our ancestors), in reflexive modernity (where we make lifestyle and other core choices rationally, by reflecting about them) and in risk society (impregnated by awareness of existential risks, which we don't know how to handle). Our situation demands that we create reliable information about life's basic issues. Reliability, and rigor, here are not in the process, but in (as Erich Jantsch called it) "process of process"—i.e. in the way in which the methods and processes evolve.

- Polyscopy is a prototype; it is explicitly defined by a collection of principles that are defined by convention. Hence it provides explicit guidelines for creating and using information. Those guidelines are themselves federated—and hence subject to change, when the society's needs or the knowledge of knowledge demand that. The formulation of a methodology gives us a way to spell out the assumptions and the rules—and provide the much-needed scientifically-based criteria and methods by which information is handled in our society.

- The method of polyscopy too are federated—by distilling and combining methodological insights in relevant traditions.

The methodological approach allows us to extend the project science to encompass all themes that are of interest—and give priority to the most urgent or vital ones.

A methodology is in essence a toolkit; anything that does the job would do. We, however, defined polyscopy by turning state of the art epistemological and methodological insights into conventions.

By doing hat, we showed how the severed evolutionary tie—between fundamental and methodological insights, and the way we the people look at the world—can be restored.

The polyscopy definition comprises eight aphorismic conventions called postulates; by using truth by convention, each of them is given an interpretation.

The first postulate defines information as "recorded experience". It is thereby made explicit that the substance communicated by information is not "reality", but human experience. Since human experience can be recorded in a variety of ways (a chair is a record of experience related to sitting and chair making), the notion of information is extended well beyond written documents.

The first postulate enables knowledge federation across cultural traditions and fields of interests; the barriers of language and method are removed by giving cultural artifacts a 'common denominator'—human experience.

To be able to say that we "know" anything, we must federate not only the supporting evidence, but also potential counter-evidence—and hence information at large.

As a principle or a rule of thumb, knowledge federation is a radical departure from the now common practice—where what information we consider useful and valid is determined by our socialized self-identity: A Christian will as a rule not feel the need to know about Buddhism and Islam, and vice versa; a scientist may consider it as part of his self-identity to ignore all three. The story of the Tower of Babel points to the nature of the situation we are in—which knowledge federation undertakes to overcome.

The change we are proposing is like the historical change to constitutional democracy, and to the legal ethos and praxis that resulted. Today even a hated criminal is given the benefit of a fair trial. Like a dutiful attorney, knowledge federation does its best to gather evidence, and back each potentially relevant cultural artifact or experience with a convincing case.

The second postulate is that the scope (the way we look) determines the view (what we see). In polyscopy the experience (or "reality" or whatever is "behind" experience) is not assumed to have an a priori structure. We attribute to it a structure with the help of the concepts and other elements of our scope.

The second postulate enables us to create new ways of looking at the world; and by doing that, extend the approach of science to all questions of practical interest.

The second postulate also enables us to state and justify or 'prove' scientific-like result in any domain of interest. Such justification has two parts. One of them is to show that the offered insight is consistent with the data, consistent with lower-level insights. But such consistency, the rewarding "aha" feeling we get when the details fit together, is not sufficient to establish a result. That things make sense is here treated as no more than a mnemonic device, a most useful way to condense information to an insight or principle. This insight or principle, however, must be shown to be a necessary element in a larger whole. We must also validate the scope used to create it as view.

The methodology definition allows us to state explicitly the criteria that orient everyday handling of information. We used this approach to define, for instance, what being "informed" means. We modeled this intuitive notion with the keyword gestalt. To be "informed", one needs to have a gestalt that is appropriate to one's situation. "Our house is on fire" is a canonical example. The knowledge of a gestalt is profoundly different from only knowing the data (such as the room temperatures and the CO2 levels.). To have an appropriate gestalt means to be moved to do the action that the situation at hand is calling for.

Are we misinformed—in spite of all the information and information technology we own?

Could we be living in a misapprehended "reality"—which obscures from us the true nature of our situation, and the way we need to act?

"One cannot not communicate", reads one of Paul Watzlawick's axioms of communication. Even when everything in a media report is factually correct, the gestalt it conveys implicitly can entirely miss the mark—because we are told what Donald Trump has said; and not Aurelio Peccei.

Polyscopy offers a collection of techniques for 'proving' or justifying, and also communicating, the gestalts and other general or high-level insights and claims. Those techniques are, of course, also federated:

- Patterns, defined as "abstract relationships", are federated from science and mathematics; they have a similar role as mathematical functions do in traditional sciences; by being generally applicable and defined by convention, they no longer constitute a narrow frame

- Ideograms allow us to adapt the techniques from the arts, advertising and communication design, and give expressive power to gestalts, patterns and other insights

- Vignettes implement the basic technique from media informing, where an insight or issue is made accessible by telling illustrative and "sticky" real-life people and situation stories

- Threads implement Vannevar Bush's technical idea of "trails", and provide a way to combine specific insights into higher-level units of meaning

In the manner of a fractal, the following vignette will further explain why we need to federate the we look at the world, to be able to comprehend and handle it—both in the academia and in general; and illustrate the benefits that will result.

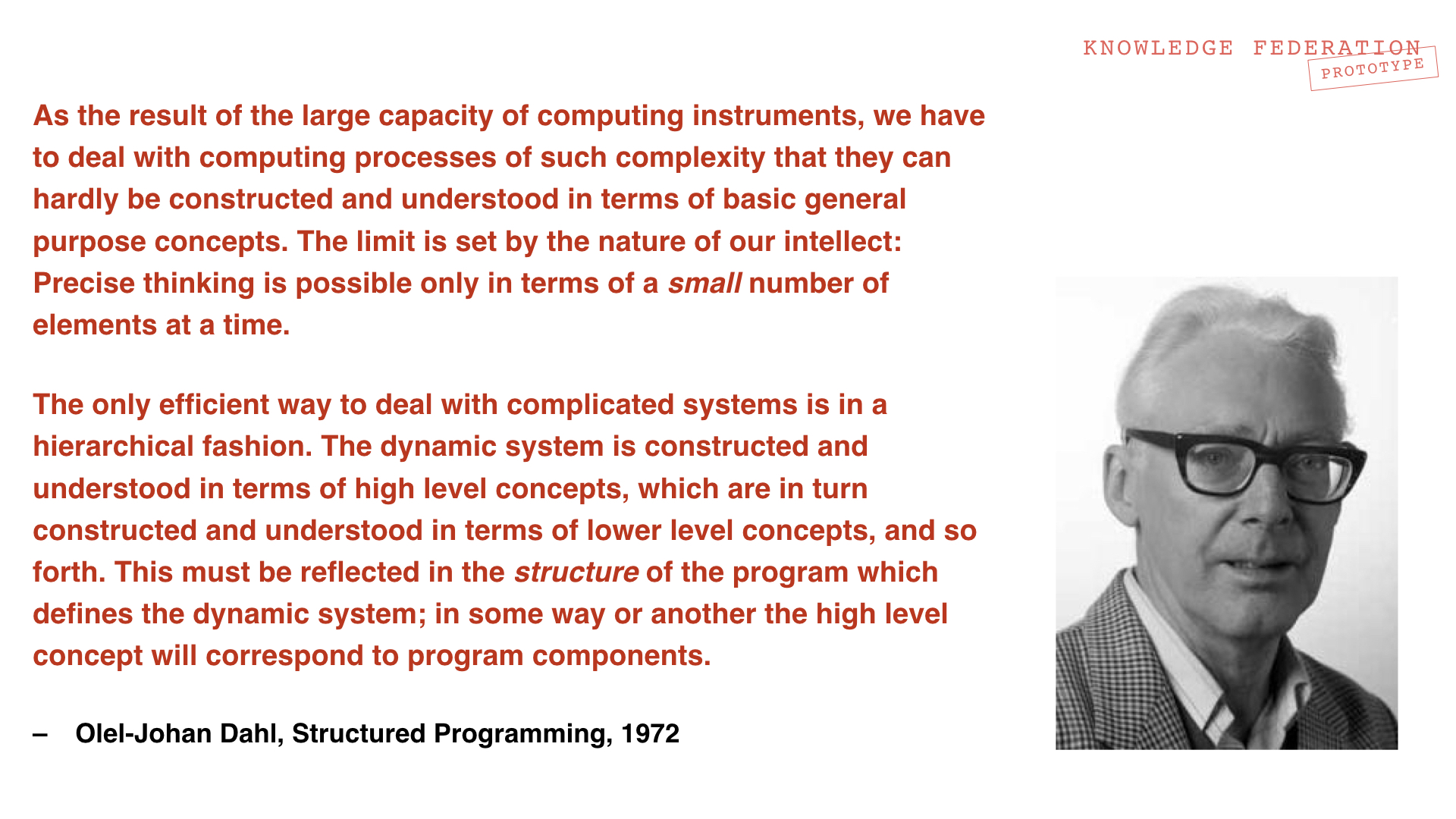

A situation with overtones of a crisis arose in the early days of computer programming. The buddying computer industry undertook ambitious software projects—which resulted in thousands of lines of "spaghetti code", which no-one could understand and correct.

The solution was found in creating "computer programming methodologies", of which the "object oriented methodology", developed in the 1960s by Ole-Johan Dahl and Krysten Nygaard, is a prime example. The longer story is interesting but we already shared it, so here we only highlight its main point, and offer a conclusion.

Any sufficiently complete programming language will allow the programmers to create any application program. The creators of the object oriented methodology, however, made themselves accountable for providing the programmers the conceptual and programming tools that would enable them, or even compel them, to write comprehensible, reusable and well-structured code.

When a team of programmers can no longer understand the program they have created, their problem is easily detected—because the program will not compile or run on the computer. But when a human generation can no longer understand the information they have created, or the world this information is supposed to explain—isn't that exactly the situation that The Club of Rome and Aurelio Peccei have diagnosed?

We may conclude from this parallel, and from the socialized reality insight:

The academia too must consider itself accountable for the tools and processes it gives to its members; and to our society at large.

The structuring template the creators of the object oriented methodology conceived and gave to the programmers is called "object". The core purpose of an "object" is to "encapsulate" or "hide" implementation, and provide or "export" function. "Object" is a piece of code that interfaces with the rest of the program through a collection of functions it provides. A printer may provide the function "print"; a scanner the function "scan"—and only those functions are visible in the "higher-level" code. The code by which those functions are implemented is made available separately.

The solution for information structuring we proposed within polyscopy is called information holon (we adapted the keyword "holon" from Arthur Koestler, who used it as a name for something that is both a whole, and a part in a larger whole). An information holon is closely similar to the "object" in object oriented methodology. The information, represented by the "i", is depicted as a circle on top of a square. This suggests the structuring principle, where the square represents a multiplicity of ways of looking, and contributing data and insights, and the circle represents the point of it all (such as 'the cup is broken'). As the case is with the "object", the information holon "encapsulates" the data within the square, and makes only the function available to the rest of the world as the circle.

When the circle is a general insight or a gestalt, the details that comprise the square are given the power to influence our awareness of issues, and the way in which we handle them. When the circle is a prototype, the multiplicity of insights that comprise the square are given direct systemic impact, and hence agency.

The information holon allows us to implement also the structuring principle, which the creators of the object oriented methodology conceived as the solution to their challenge.

Dahl's point, that "precise thinking is possible only in terms of a small number of elements at a time", must be federated and applied in our work with knowledge at large.

This means that we must be able to create small, manageable snapshots of "reality" (or whatever may be its part or issue we are considering), on any desired level of detail or generality; and that we must devise ways of organizing and inter-relating such views to compose a coherently structured whole.

We adapted or federated Dahl's insight by declaring a collection of principles that define polyscopy. We point to them by the metaphor of the mountain—and visually by the triangle in the Information ideogram.

To understand them, imagine taking a mountain walk: We may look at the valley down below, and see lakes, forests and villages; or at the trees that surround us; or zoom in on a flower and inspect its details. In each case, what we see is a simple and coherent view ("coherent" because it represents a single level of detail). It is in the nature of our perception that we are always given a coherent view—along with the awareness of the position our view occupies relative to other views, and to the world at large. The aim of polyscopy is to preserve that basic quality of our perception, which enables us to make sense of our views—by comprehending each of them and by contextualizing them correctly—also in the work with human-made and abstract information.

It is clear that this way of organizing and maintaining knowledge requires on the one side a new collection of social processes, by which the high-level views or circles are kept consistent with the corresponding squares, and with each other. And on the other side a general-purpose methodology, by which we can create new high-level concepts (corresponding to 'village', 'forest' and 'lake'), on any level of generality.

The required social processes are modeled by knowledge federation; the methodology by polyscopy.

The Holotopia prototype may now be understood as the circle that completes our knowledge federation proposal; which federates the proposal.

It is customary in programming methodology design to showcase the programming language that implements the methodology by creating its first compiler in the language itself. We applied the same approach and created a polyscopic book manuscript, titled "Information Must Be Designed".

In this book we described the paradigm that is modeled by polyscopy; and used polyscopy to make a case for that paradigm. The book's introduction provides a summary.

What we at the time this manuscript was written called information design, has subsequently been completed and rebranded as knowledge federation.

Scope

We turn to culture and "human quality", and ask:

Why is "a great cultural revival" realistically possible?

What insight, and what strategy, may divert our "pursuit of happiness" from material consumption and egocentricity to human cultivation?

We approach this theme also from another angle: Suppose we developed the praxis of federating knowledge—and used it to combine the heritage and insights from the sciences, world traditions, therapy schools...

If we used federated knowledge instead of advertising to guide our choices—what changes would develop? What difference would that make?

The Renaissance liberated our ancestors from worries about the original sin and the eternal reward, and they began to pursue happiness and beauty, here and now.

What values might the next "great cultural revival" bring to the fore?

Diagnosis

In the course of modernization we made a cardinal error—by adopting convenience as our cardinal value.

By convenience we mean the unwavering faith—now so common—in direct experience as way to determine what is to be considered as "good", "desirable" and "worthy of being pursued". We define convenience rather broadly, and let it subsume also the closely related value egocenteredness or egocentricity—which we use, for instance, to decide what parties and policies to vote for, based on how their stated agendas affect our own personal needs and desires.

This error can easily be understood as a consequence of the narrow frame—the fact that we've been socialized to mistake the rewarding "aha" emotion when we understand how a certain cause leads to a certain effect as a sign that we've seen the very "reality" of that phenomenon. And so naturally, what feels attractive or pleasant gets reified as "the cause" of happiness. The scientists have the experiment to provide them the reality touch and the data for reasoning and action; the rest of us have convenience.

But convenience is, of course, also a product of our socialized reality. Advertising may promote all kinds of products; but on a more basic level—it always promotes convenience, by appealing to convenience.

And so since we believe that we already know what our goals and purposes should be, the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom has no practical value for us, and no esteem. We not seek information to orient our choices.

Convenience orients even our choice of information!

Remedy

To comprehend the remedy we are about to propose, it is best to imagine that we are already living on the other side of the metaphorical mirror—that we handle information as we now handle other human-made things, by adapting it to the purposes that need to be served. That, furthermore, the narrow frame has been unraveled, and that we are capable of creating basic insights about all basic things in life; not the least—about values.