Difference between revisions of "STORIES"

m |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | <div class="page-header" > <h1>Federation through | + | <div class="page-header"><h1>Federation through Keywords</h1></div> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

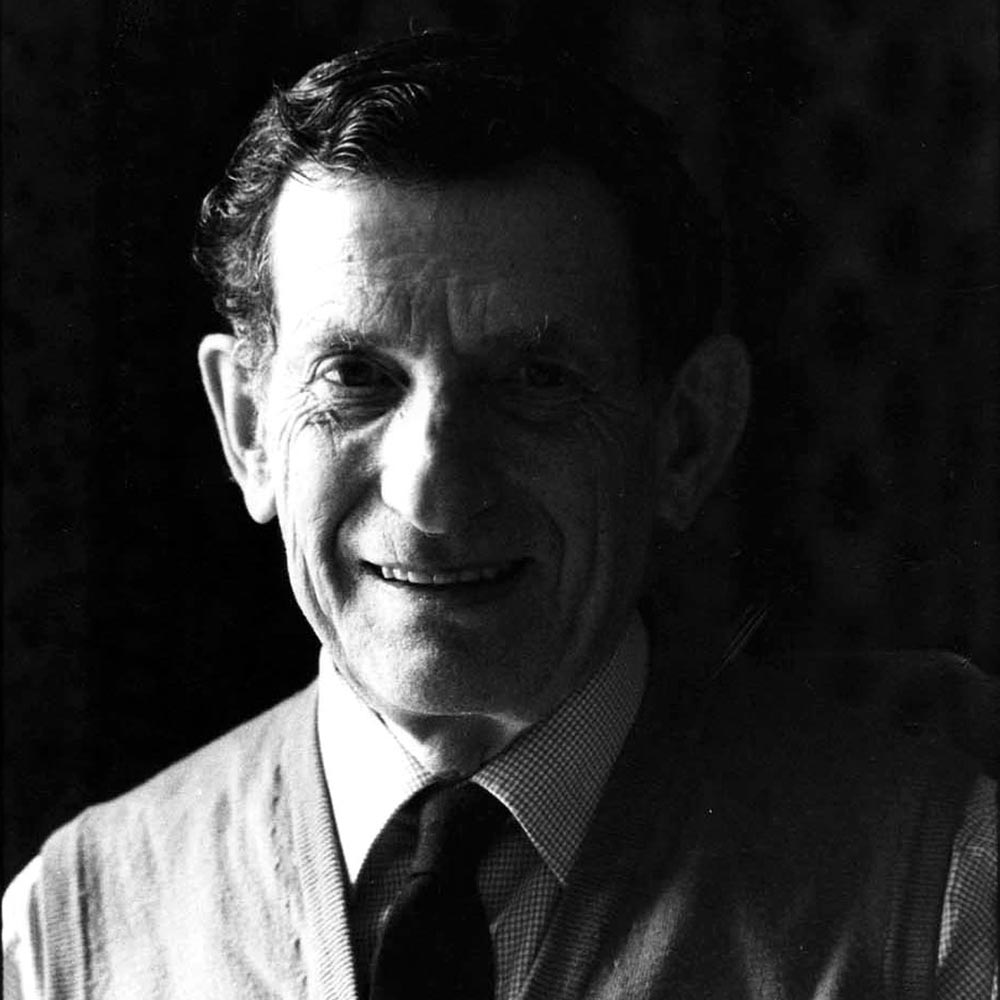

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1"> “I cannot understand how anyone can make use of the frameworks of reference developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth century in order to understand the transformation into the post-traditional cosmopolitan world we live in today.”</font><br> | |

| − | + | (Ulrich Beck, <em>The Risk Society and Beyond</em>, 2000)</div> | |

| − | <p> | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>The key to stepping <em>beyond</em> the "risk society" (where existential risks we can't comprehend or handle lurk in the dark) is to <em><b>design</b></em> new ways to see and speak—as the Modernity ideogram suggested. The very <em>approach</em> to <em><b>information</b></em> the <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em> enables is called <em><b>scope design</b></em>, where <em><b>scopes</b></em> are what determines <em>what</em> we look at and <em>how</em> we see it. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <h3>We can <em>design scopes</em> by creating <em>keywords</em>.</h3> |

| − | < | + | <p>Because <em>keywords</em> are defined in the way that's common in mathematics—by <em><b>convention</b></em>. When I turn "culture", for instance, into a <em><b>keyword</b></em>—I am not saying what culture "really is"; but creating <em>a way of looking</em> at the infinitely complex real thing; and thereby <em>projecting</em> it, as it were, onto a plane—so that we may look at it from a specific side and comprehend it precisely; and I'm inviting you, the reader, to <em><b>see</b></em> culture <em><b>as</b></em> it's been defined.</p> |

| − | + | <p><em><b>Keywords</b></em> enable us to give old words like "science" and "religion" new meanings; and old institutions a function, and a new life. </p> | |

| − | < | + | <h3><em>Keyword</em> creation is a form for linguistic and institutional recycling.</h3> |

| − | < | + | <p>Often but not always, <em><b>keywords</b></em> are adopted from the repertoire of a frontier thinker or an academic field; they then enable us to <em><b>federate</b></em> what's been comprehended and seen in our culture's dislocated compartments.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <h3><em><b>Keywords</b></em> enable us to 'stand on the shoulders of giants' and see further.</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | </div> |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-3">[[File:Beck.jpeg]] <br><small><center>[[Ulrich Beck]]</center></small></div> |

| − | < | + | </div> |

| − | < | + | <div class="row"> |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| − | <li> | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Paradigm</h2> |

| − | </ul> </p> | + | </div> |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>I cannot think of a better illustration of the power of <em><b>seeing things whole</b></em>—by <em><b>designing</b></em> the way we look—than these <em>wonderful</em> paradoxes I am about to outline; which <em><b>paradigm</b></em> as keyword points to; which <em><b>holotopia</b></em> as initiative undertakes to overcome.</p> | ||

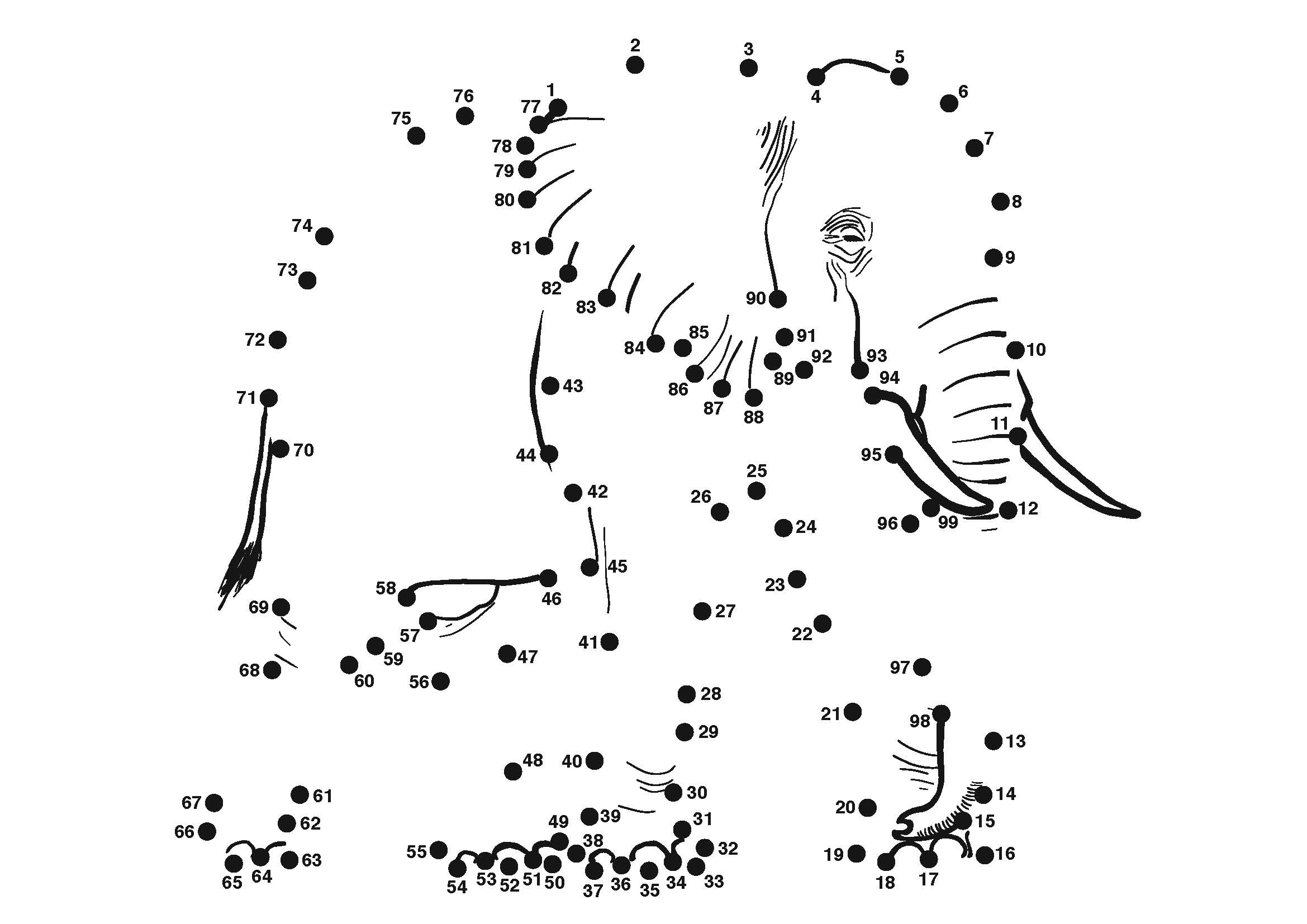

| + | <p>[[File:Elephant.jpg]]<br><small><center>To see an emerging <em><b>paradigm</b></em>, we must connect the dots.</center></small></p> | ||

| + | <p>I use the keyword [[paradigm|<em><b>paradigm</b></em>]] informally—to point to a societal and cultural order of things; and when I want to be even more informal—I use <em><b>elephant</b></em> as its nickname; to highlight that in a <em><b>paradigm</b></em> everything depends on everything else—just as the organs of an <em><b>elephant</b></em> do.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The <em><b>paradigm</b></em> is the very (social and cultural) "reality" we live in; to which we <em>must</em> conform in order to succeed in <em>anything</em>; because when we don't—and end up failing—we quickly learn that certain things just don't work, and must be avoided. And so willy-nilly—we become <em>part of</em> the <em><b>paradigm</b></em>; and let it determine what we consider "realistic", or possible.</p> | ||

| + | <p>So here's a paradox: The <em><b>paradigm</b></em> we live in could be <em>arbitrarily</em> dysfunctional, non-sustainable and downright <em>suicidal</em>—and we'll <em>still</em> we'll consider complying to its limitations as (the only) way to "success"; and everything else as impractical or "utopian".</p> | ||

| + | <p>And here's another one: Comprehensive change (of the <em><b>paradigm</b></em> as a whole) can be natural and easy—even when attempts to do small and obviously necessary changes have proven impossible; you <em>can't</em> fit an elephant's ear onto a mouse! <em><b>Paradigms</b></em> <em>resist</em> change—that goes against the grain of their <em>order of things</em>. And yet changing the <em><b>paradigm</b></em> as a whole can be natural and even easy—when the conditions for such a change are ripe.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>We live in such a time.</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The <em>Liberation</em> book demonstrates that; by developing an analogy between the times and conditions when Galilei was in house arrest—when the Enlightenment was about to spur comprehensive change—and our own time. The <em>Liberation</em> book then proposes—and ignites—a <em>process</em>; by which we'll <em>liberate</em> ourselves from the grip of our <em><b>paradigm</b></em>; which, needless to say, needed to be <em><b>designed</b></em>; because no matter how hard we may try—we'll <em>never</em> produce the lightbulb by improving the candle!</p> | ||

| + | <p>I use the keyword <em><b>paradigm</b></em> also formally, as Thomas Kuhn did—to point to | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>a different way to conceive a domain of interest, which</li> | ||

| + | <li>resolves the reported anomalies and</li> | ||

| + | <li>opens a new frontier for research and development.</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

| + | </div></div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Logos</h2></div> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3">< | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“Some years ago I was struck by the large number of falsehoods that I had accepted as true in my childhood, and by the highly doubtful nature of the whole edifice that I had subsequently based on them. I realized that it was necessary, once in the course of my life, to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations if I wanted to establish anything at all in the sciences that was stable and likely to last.” </font> |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | <div class="col-md-6">< | + | (René Descartes, <em> Meditations on First Philosophy</em>, 1641) |

| − | <p> | + | </div> |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p><em>The</em> natural way to enable the <em><b>paradigm</b></em> to change is by changing the way we the people use our minds; as what I just pointed to, the change spurred by the Enlightenment, may illustrate. And it is that very strategy I am inviting you to follow; because the way we use the mind is <em>again</em> ripe for change.</p> |

| − | + | <p>I use the word <em><b>logos</b></em> to <em>problematize</em> the way we use the mind; so that instead of taking it for granted, instead of simply <em>using</em> the mind as we're accustomed to, we recognize it as <em>problematic</em>; and begin to pay attention to the very <em>way</em> we use the mind. In the <em>Liberation</em> book I do that by pointing to its <em>historicity</em>; so we may see the way we use the mind as a product of historical circumstances and beliefs; as something that <em>has</em> changed before and <em>can</em> change again. </p> | |

| − | + | <p>"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and logos was God." To the philosophers of antiquity, "logos" was the very principle according to which God created and organized the world; which enables us humans to comprehend the world and live and act in harmony with it, by aligning with it the way we use our minds. How exactly we should go about doing that—the opinions differed; and gave rise to a multitude of philosophical traditions.</p> | |

| − | + | <p>But "logos" faired poorly in post-hellenic world; Latin had no equivalent, and the modern languages offered none either. For about a millennium our ancestors believed that <em><b>logos</b></em> had been <em>revealed</em> to us humans by God's own son; and recorded in the Bible; and considered further quest of <em><b>logos</b></em> to be the deadly sin of pride, and a heresy.</p> | |

| − | + | <h3>The Englightenment was a revolution.</h3> | |

| − | </ | + | <p>Which brought human <em>reason</em> to power; and taught us to rely on science-empowered reason to comprehend the world and the life's core themes.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>A reason why <em>we</em> must go back to the drawing board, and do as Descartes and his Enlightenment colleagues did—is that they got it all wrong!</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <h3><em>They</em> made the error that gave us 'candles' as 'headlights'.</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>They made indeed <em>two</em> errors, to be precise; when they took it for granted that |

| − | < | + | <ul> |

| − | + | <li>the goal of the pursuit of knowledge, <em>and</em> of science, was to find the "objective" and unchanging truth about "reality"; and that</li> | |

| − | + | <li>this truth is revealed to the mind as the <em>sensation</em> of absolute certainty.</li> | |

| − | + | </ul> | |

| − | </ | + | Science was initially <em>shaped</em> by this belief; and then <em>science itself</em> proved it wrong!</p> |

| − | + | <p>The prospects to make the nature comprehensible in <em>causal</em> terms—as one might comprehend the workings of a clock—retreated every time it appeared to be close to succeeding; the ("indivisible") atom split into one hundred "subatomic particles"; which—when the scientists became able to examine them—turned out to defy not only causality but even <em>the common sense</em> (as J. Robert Oppenheimer pointed out in <em>Uncommon Sense</em>). The presumed 'clockwork of nature' turned out to be like Humpty Dumpty—something that <em>nobody</em> can put together again.</p> | |

| + | <p>That science—conceived as a collection of specialized disciplines—now occupies the larger-than-life function (of "the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture" as Benjamin Lee Whorf branded it in <em>Language, Thought and Reality</em>) was nobody's conscious design or even intention. For awhile, tradition and science coexisted side by side—the former providing <em><b>know-what</b></em> and the latter know-how. But then—right around the mid-nineteenth century, when Darwin entered this scene—science <em>ousted</em> the tradition; and becoe the modernityh's <em>sole</em> arbiter of knowledge.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>But science never <em>adjusted</em> itself to this much larger role.</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The <em><b>system</b></em> of science, as it has emerged from this evolution, has no provisions for updating the <em><b>system</b></em> of science. We seem to be simply stuck with a certain way of exploring the world; just as we are stuck with our larger <em>societal</em> <em><b>paradigm</b></em>! </p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Descartes.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Rene Descartes]]</center></small></div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Design epistemology</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“[T]he nineteenth century developed an extremely rigid frame for natural science which formed not only science but also the general outlook of great masses of people."</font> |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <br> |

| − | <p> | + | (Werner Heisenberg, <em>Physics and Philosophy</em>, 1958.) |

| − | < | + | </div> |

| − | the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>You'll easily comprehend the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> this third of <em><b>holotopia</b></em>'s <em><b>five insights</b></em> points to, if you just <em><b>see</b></em> the way we use the mind (and go about deciding what's true or false and relevant or irrelevant) <em><b>as</b></em> the foundation on which the edifice of our <em><b>culture</b></em> has been built; which enables <em>some</em> of its parts or sides to grow big and strong (which are supported by this <em><b>foundation</b></em>), and abandons others to erosion. As Heisenberg pointed out, what we have as <em><b>foundation</b></em>—which our general culture imbibed from 19th century science—<em>prevented</em> cultural evolution to continue; being "so narrow and rigid that it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our |

| − | provided, | + | language that had always belonged to its very substance, for instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul or of life." Since "the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided", whatever failed to be <em><b>founded</b></em> in this way was considered impossible or unreal. This in particular applied to those parts of our culture in which our ethical sensibilities were rooted, such as religion, which "seemed now more or less only imaginary. [...] The confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind."</p> |

| − | </ | + | <p>Heisenberg then explained how the experience of modern physics constituted a rigorous <em>disproof</em> of this approach to knowledge; and concluded that "one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century." </p> |

| − | + | <p>Heisenberg wrote <em>Physics and Philosophy</em> anticipating that <em>the</em> most valuable gift of modern physics to humanity would be a <em>cultural</em> transformation; which would result from the <em>dissolution</em> of the <em><b>narrow frame</b></em>.</p> | |

| − | + | <h3>As an insight, <em>design eistemology</em> shows how a broad and solid <em>foundation</em> can be developed.</h3> | |

| − | seemed now more or less only imaginary. | + | <p>By following the approach that is the subject of this proposal.</p> |

| − | + | <p>The <em><b>design epistemology</b></em> originated by <em><b>federating</b></em> the state-of-the-art epistemological findings; by systematizing and adapting what the <em><b>giants</b></em> of science and philosophy have found out—and writing the result as a <em><b>convention</b></em>. Here Einstein's "epistemological credo"—which he left us in <em>Autobiographical Notes</em>, his testament or "obituary", is <em>already</em> sufficient:</p> | |

| − | <p>Heisenberg then explained how the experience of modern physics constituted a rigorous <em>disproof</em> of this approach to knowledge; and concluded that | + | <p>“I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. <nowiki>[…]</nowiki> The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. <nowiki>[…]</nowiki> All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for [scientific] inquiry in the first place.”</p> |

| − | + | <h3>Modernity ideogram renders <em>design epistemology</em> in a nutshell.</h3> | |

| − | one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century. | + | <p>The <em><b>design epistemology</b></em> takes the constructivist credo (that we do not discover but <em>construct</em> a "reality picture"; which Einstein expressed succinctly) two evolutionary steps further—by writing it (no longer as a statement about reality, but) as a <em><b>convention</b></em>; and assigning to it a <em>purpose</em>.</p> |

| − | </ | + | <h3>This <em>foundation</em> is solid or "rigorous".</h3> |

| − | <em> | + | <p>Because it represents the epistemological state of the art; <em>and</em> because it's a <em><b>convention</b></em>. The added purpose can hardly be debated—<em>not only</em> because doing what's necessary to avoid civilizational collapse is hard to argue against; but also because <em>this too</em> is a <em><b>convention</b></em>; a <em>different</em> convention, and an altogether different way to knowledge can be created, to suit a <em>different</em> purpose.</p> |

| − | + | <p>A side-effect of this academic update is that it offers us a way to avoid the fragmentation in social sciences; which results when the social scientists disagree whether it's right to see the complex cultural and social reality in one way or another. Here our explicit aim is to <em><b>see things whole</b></em>; which translates into the challenge of seeing things in a way that may best reveal their non-<em><b>whole</b></em> sides. The simple point here is that when our task is <em>not</em> producing an accurate description of an infinitely complex "reality", but a way to see it that "works" (in the sense of providing us evolutionary guidance)—then the fragmentation is easily diagnosed as part of the problem; and avoided.</p> | |

| − | < | + | <p>Another philosophical stream of thought that the <em><b>design epistemology</b></em> embodies is <em><b>phenomenology</b></em>; which Einstein pointed to by talking about "the totality of sense experiences" on the one side, and "the totality of the concepts and propositions" on the other side; a point being that <em>human experience</em> (and not "objective reality") is the substance that <em><b>information</b></em> can and needs to be founded on, and represent. This allows us to treat not only the sciences—but indeed <em>all</em> cultural traditions and artifacts as 'data'; which in some way or other embody human experience.</p> |

| − | < | + | <h3>This <em>foundation</em> is also broad.</h3> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>In the sense that it removes completely the <em><b>narrow frame</b></em> anomaly; and lets us build knowledge, and culture, on <em>all</em> forms of human experience. By convention, experience does not have any a priori structure; experience is considered to be like the ink blot in a Rorschach test—something to which we freely <em>ascribe</em> interpretation and meaning; as Einstein suggested we should, by formulating his "epistemological credo".</p> |

| − | <p><em> | + | </div> |

| − | <p> | + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Heisenberg.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Werner Heisenberg]]</center></small></div> |

| − | <p> | + | </div> |

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Polyscopic methodology</h2></div> | |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3">< | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”</font> |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | (Abraham Maslow, <em>Psychology of Science</em>, 1966) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>You'll comprehend the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> this fourth of <em><b>holotopia</b></em>'s <em><b>five insights</b></em> points to, if you <em><b>see</b></em> the method—the category from which it stems—<em><b>as</b></em> the toolkit we use to construct truth and meaning; and the culture at large; and consider that—as Maslow pointed out—this method is so specialized that it compels <em>us</em> to be specialized; and choose our themes and set our priorities (not according to their relevance, but) according to what this <em>tool</em> enables us to do.</p> | ||

| + | <p>As an <em>insight</em>, the <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em> points out that a general-purpose method, which alleviates this problem, can be created by the proposed approach; by <em><b>federating</b></em> the findings of <em><b>giants</b></em> of science and the techniques developed in the sciences; so as to preserve the advantages of science—and alleviate its limitations.</p> | ||

| + | <p><em><b>Design epistemology</b></em> mandates such a step: When we on the one hand acknowledge that (as far as we <em><b>know</b></em>) <em> there is no</em> conclusive truth about reality; and on the other hand, that our very <em>existence</em> depends on <em><b>information</b></em> and <em><b>knowledge</b></em>—we are bound to be <em>accountable</em> for providing <em><b>knowledge</b></em> about the most relevant themes (notably the ones that determine our society's evolutionary <em><b>course</b></em>) <em>as well as we are able</em>; and of course to continue to improve both our <em><b>knowledge</b></em> and our <em>ways</em> to <em><b>knowledge</b></em>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>As long as "reality" and its "objective" descriptions constitute our only reference system—we have no way of evaluating our <em><b>paradigm</b></em> critically; all we can do is <em>adapt</em> to it; By building on what I've just told you, <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em> enables us to develop the <em><b>realm of ideas</b></em> as an independent reference system; on <em><b>truth by convention</b></em> as <em><b>foundation</b></em>; and (the ideas being conceived as abstract simplification)—develop rigorous theories that help us relate not only ideas, but the corresponding elements of our society and culture too; in a moment I'll clarify this by an example.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em> provides methods for a <em><b>transdisciplinary</b></em> approach to <em><b>knowledge</b></em>; where <em><b>patterns</b></em>, defined as "abstract relationships", have a similar function as mathematical functions do in conventional science—they enable us to formulate general results and theories; <em>including</em> <em><b>gestalts</b></em>; suitable method for <em><b>justifying</b></em> or 'proving' such results are provided, which <em><b>design epistemology</b></em> made possible.</p> | ||

| + | <p>The <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em> allows us to define what <em><b>information</b></em> needs to be like; and in this way exercise the accountability I pointed to when I talked about the analogy with computer programming, and the related methodologies.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | -- | + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Maslow.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Abraham Maslow]]</center></small></div> |

| + | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"><h2> | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Convenience paradox</h2></div> |

| − | <p>< | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> </div> |

| − | + | <div class="row"> | |

| − | </ | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future.” </font> |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | <h3> | + | (Aurelio Peccei, <em>One Hundred Pages for the Future</em>, 1981) |

| − | <p> | + | </div> |

| − | <p> | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>You'll appreciate the <em>importance</em> of the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> the <em><b>convenience paradox</b></em>—the fifth of <em><b>holotopia</b></em>'s <em><b>five insights</b></em>—is pointing to, if you consider it in the context of the need to <em><b>change course</b></em> by shifting the current focus of our striving from material production and consumption to humanistic and <em>cultural</em> pursuits and values; the need of which everyone who has studied our evolutionary challenges and opportunities seems to have agreed on; which with new information technology—you may now hear [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7Z6h-U4CmI straight from the horse's mouth]! </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>And you'll see the anomaly itself if you reflect for a moment how Heisenberg described the <em><b>narrow frame</b></em> (the way to see and comprehend the world that defined our cultural <em><b>paradigm</b></em>, which is now ripe for change); where "the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided"; and notice that this way to conceive of "reality" leaves in the dark one whole <em>dimension</em> of reality—time; and one might say, one whole half or side of space too—its <em>inner</em> or embodied side; so that the only thing we can perceive and comprehend and work with is <em><b>convenience</b></em>—whereby we seek, and reach out to get, what <em>feels</em> attractive or fun, and vice versa.</p> |

| − | < | + | <h3><em>Convenience</em> leaves in the dark a myriad possibilities for developing <em>human quality</em>.</h3> |

| + | <p>Which is what <em><b>culture</b></em> is all about <em>by definition</em>. </p> | ||

| + | <p>As an insight, and a proof-of-concept result of applying <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em>, and as a quintessential <em><b>information holon</b></em>—the <em><b>convenience paradox</b></em> points to the sheer absurdity of <em><b>convenience</b></em> as value; and to a myriad possibilities to <em>radically</em> improve the human condition through <em><b>cultural</b></em> means.</p> | ||

| + | <h3><em>Convenience paradox</em> is point of inception of an entirely new <em>culture</em>.</h3> | ||

| + | <p>The <em>Liberation</em> book can be read in several different ways; but one of the more interesting ones is undoubtedly to see it as a roadmap to a <em><b>whole</b></em> human condition; where the first five chapters describe the <em>inner</em> <em><b>wholeness</b></em>; and the remaining five chapters the <em>outer</em> <em><b>wholeness</b></em>; and the overall effect is to see that those two are closely interdependent and indeed <em>undistinguishable</em>; and that <em><b>wholeness</b></em> indeed <em>is</em> the value or 'destination' we'll most <em>naturally</em> pursue—as soon as we use <em>real</em> light to see and navigate the world.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Then you may also see the <em>Liberation</em> book as a template for comprehending and evaluating things and ideas—notably the culture-transformative <em><b>memes</b></em>—(not by fitting them into the existing <em><b>paradigm</b></em>, where they don't fit in by definition, but) by fitting them into the <em>emerging</em> order of things; by seeing them as part and parcel of an emerging <em><b>whole</b></em> human condition; as portrayed by <em><b>holotopia</b></em>, or the <em><b>elephant</b></em>.</p> | ||

| + | <h3>This template is produced by <em>federating</em> two insights reached by Buddhadasa—Thailand's holy man and Buddhism reformer.</h3> | ||

| + | <p>By seeing them as <em>necessary</em> elements of (our quest for) <em><b>wholeness</b></em>. The first of Buddhadasa's insights, which I call in the book <em><b>origination of conditioning</b></em>, turns our conventional "pursuit of happiness" (conceived as pursuit of <em><b>convenience</b></em>) on its head! And the second, that <em><b>wholeness</b></em> demands that we liberate ourselves from <em><b>self-centeredness</b></em>, which he saw as <em>the</em> shared trait of Buddhism with the great world religions; which the book's subtitle "Religion beyond Belief" points to. The point here is to comprehend <em>why</em> <em><b>self-centeredness</b></em> and <em><b>convenience</b></em> only appear to us as valuable when we see the way in the light of a pair of candles; and thoroughly <em>disastrous</em> when we <em><b>see things whole</b></em>. I feel tempted to improvise now, and tease you a bit; so here's something we may take up in our <em><b>dialog</b></em>; the history of <em><b>religion</b></em> (seen as a <em>function</em> in culture—to liberate us from self-centeredness) may now be seen as having three phases; where first | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>belief was used to coerce people to do the right thing; and then</li> | ||

| + | <li>beliefs of tradition were dispersed and new beliefs, of <em><b>materialism</b></em> introduced; and the people ended up doing the <em>wrong</em> thing; until finally</li> | ||

| + | <li>we developed the ability to <em><b>see things whole</b></em>; and see <em><b>religion</b></em> (understood as that side of culture that develops <em><b>human quality</b></em> and eliminates <em><b>self-centeredness</b></em> and various defects it produces) as <em>necessary</em> for <em><b>making things whole</b></em>.</li> | ||

| + | </ul></p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File: | + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Peccei.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Aurelio Peccei]]</center></small> |

| + | </div> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Knowledge federation</h2></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“Many years ago, I dreamed that digital technology could greatly augment our collective human capabilities for dealing with complex, urgent problems."</font> |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <br> |

| − | < | + | (Doug Engelbart, "Dreaming of the Future*, <em>BYTE Magazine</em>, 1995) |

| − | < | + | </div> |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>The <em><b>pivotal</b></em> category from which <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>—the second of <em><b>five insights</b></em>—stems is "communication"; which here means specifically the collection of <em>processes</em> by which we the people communicate; enabled by information technology. You'll easily see the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> this insight points to if you think of <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em> as <em>the</em> radical alternative to publishing or broadcasting—the process that was enabled by the earlier technological revolution, the printing press; and think how much the <em><b>belief</b></em> that when something is published it is also "known"—which still marks the academic culture and in particular its process—is removed from reality.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>What will help you <em>complete</em> the analogy between our present processes of communication and the candle headlights is the fact that the "digital technology"—the interactive, network-interconnected digital media, which you and I use to write emails and browse the Web—has been <em>created</em>, by Doug Engelbart and his SRI-based team, as <em>the</em> enabling technology for an entirely different process; which <em>we</em> call <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>.</p> |

| − | + | <p>This <em><b>Incredible History of Doug Engelbart</b></em>, as I ended up calling it, is <em>the</em> best story I know of to illustrate the opportunities that are germane in the emerging <em><b>paradigm</b></em> and the obstacles we have to face. I wrote it up as a book manuscript draft; and then left it to be published as the second book in the <em><b>holotopia</b></em> series; and wrote a very brief version in Chapter Seven of the <em>Liberation</em> book, which has "Liberation of Society" as title. The fact that Engelbart was unable to communicate his vision to the Silicon Valley academia and businesses—no matter how hard he tried, even after he was widely recognized as <em>the</em> <em><b>giant</b></em> behind "the revolution in the Valley"—is <em>the</em> most vivid illustration of exactly the core issue I've been telling you about; how much we are stuck in "reality" of the present <em><b>paradigm</b></em>—without conceptual and cognitive tool, or even the <em>time</em> to think deeply enough to comprehend things in new ways.</p> | |

| − | < | + | <p>I use <em><b>collective mind</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em> to pinpoint the gist of Engelbart's vision; which is that the technology that Engelbart envisioned and created is <em>the</em> enabling technology for <em>the</em> capability we need—the capability to handle complex and urgent problems; because it constitutes a 'collective nervous system' that enables us develop entirely <em>new</em> processes in communication—and think and act and inform each other in a similar way in which the cells of an evolutionarily evolved organism co-create meaning and communicate. Imagine what would happen if your own cells used your nervous system to merely <em>broadcast</em> data—and you'll have no difficulty comprehending the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> that <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em> undertakes to resolve.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>Our 2010 workshop—where we <em>began</em> to self-organize as a <em><b>transdiscipline</b></em>—was called "Self-Organizing Collective Mind". Prior to this workshop I spent the school year on sabbatical in San Francisco Bay Area; and strengthened the ties with the R & D community that grew around Engelbart called Program for the Future, which Mei Lin Fung initiated in Palo Alto to continue and complete the work on implementing Engelbart's vision; and of course with Engelbart himself. At the University of Oslo Computer Science Department I later taught a doctoral course about Engelbart's legacy—to research it thoroughly, and develop ways to communicate it.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>[[File:TNC2015.jpeg]]<br><small><center>Knowledge Federation's Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 workshop in Sava Center, Belgrade.</center></small></p> |

| − | < | + | <p>As an insight, <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em> stands for the fact that a <em>radically</em> better communication is both necessary and possible; exactly the sort of quantum leap that the Modernity ideogram is pointing to. We made this possibility transparent by developing a portfolio of <em><b>prototypes</b></em>—real-life models of socio-technical systems in communication; which I'll here illustrate by our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 prototype as canonical example; where the result of an academic researcher, Dejan Raković of the University of Belgrade, has been <em><b>federated</b></em> in three phases; where |

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p>[[File: | ||

| − | <p></ | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| − | <li> | + | <li>the first phase made the result <em>comprehensible</em> to a larger audience; by turning his research into a multimedia object (this was done by <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em> communication design team); where its main points were extracted and made comprehensible by explanatory diagrams or <em><b>ideograms</b></em>; and further explained by placing on them links to recorded interviews with the author;</li> |

| − | < | + | <li>the second phase made the result <em>known</em> and at the same time discussed in space—by staging a televised high-profile <em><b>dialog</b></em> at Sava Center Belgrade;</li> |

| − | <li> | + | <li>the third phase organized a social process around the result (by using DebateGraph); a sort of updated and widely extended "peer reviews", through which global experts were able to comment on it, link it with other results and so on.</li> |

| − | </ | + | </ul> </p> |

| − | < | + | <p>As I explained in Chapter Two of the <em>Liberation</em> book, which has "Liberation of Mind" as title, also the <em>theme</em> of Raković's result was perfectly suited for our purpose: He showed <em><b>phenomenologically</b></em> that creativity (of the "outside the box" kind, which we the people now vitally need to move out of our evolutionary entrapment and evolve further) requires the sort of process or <em><b>ecology of mind</b></em> that has become all but impossible to us the people (by recourse to Nikola Tesla's creative process, which Tesla himself described)—and then theorized it within the paradigm of quantum physics. To help you fully comprehend the nature of this project I'll highlight also the point where a Serbian TV anchor (while interviewing the <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>'s representative and the US Embassy's cultural attache, who represented a sponsor) concluded "So you are developing a <em>collective</em> Tesla!". In this time when machines have become capable of doing the "inside the box" thinking for us—it has become all the more important for us to comprehend and develop the <em>kind of</em> creativity that only humans are capable of; on which our future will depend.</p> |

| − | + | <p>To fully comprehend the relevance of this insight to our general urgent task—to enable the <em><b>paradigm</b></em> to change—its synergy with <em><b>polyscopic methodology</b></em>, the fourth insight, needs to be comprehended. You'll notice that in Holotopia ideogram those two insights are joined by a horizontal line—one of <em><b>holotopia</b></em>'s <em><b>ten themes</b></em>—that has "information" as label. It is only when we've done our homework on the theory side—and explained to each other <em>and</em> the world what <em><b>information</b></em> must be like, to serve us the people in this moment of need—that we'll be able to use the new technology to <em>implement the processes</em> that this <em><b>information</b></em> requires. In the <em><b>holotopia</b></em> context this larger-than-life opportunity is pointed to by the coined idiom <em><b>holoscope</b></em>; and by <em><b>see things whole</b></em> as the related vision statement. Indeed—any sort of crazy <em><b>beliefs</b></em> can be, and have been throughout history, maintained by taking things out of their context; and by showing their one side and ignoring the other. It is only when we are able to <em><b>see things whole</b></em> that <em><b>knowledge</b></em> will once again be possible.</p> | |

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3 "> [[File:Engelbart.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Doug Engelbart]]</center></small></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3" | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md-6">< | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Systemic innovation</h2></div> |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <div class="col-md-3" | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“The task is nothing less than to build a new society and new institutions for it. With technology having become the most powerful change agent in our society, decisive battles will be won or lost by the measure of how seriously we take the challenge of restructuring the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.”</font> | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | (Erich Jantsch, <em>Loooong title</em>, MIT Report,1969) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>The importance of what I'm about to share cannot be overrated; so I'll allow myself to be blunt: You'll see the <em><b>anomaly</b></em> that this third of the <em><b>five insights</b></em> points to if you imagine the <em><b>systems</b></em> (in which we live and work) as gigantic machines comprising people and technology; which determine <em>how</em> we live and work—and importantly what the <em>effects</em> of our work will be; whether they'll be problems, or solutions; and if you then ask: If the <em><b>systems</b></em> whose function is to <em><b>inform</b></em> us and provide us comprehension and meaning a functional <em><b>know-what</b></em> are scandalously nonsensical—<em>what about all others</em>? What about our financial system, and governance, and international corporations and education? At our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 event in Belgrade someone photographed me lifting up and showing my smartphone; which I did to point to the <em>surreal</em> contrast between the dexterity that went into to creation of the little thing I was holding in my hand—and the complete negligence of incomparably larger and equally more important <em><b>systems</b></em> by which human creativity and knowledge are being handled.</p> | ||

| + | <p>In Chapter Seven of the <em>Liberation</em> book, I introduced the very brief version of the story of Doug Engelbart and Erich Jantsch (whose details I left for Book Two) by qualifying it as the environmental movement's forgotten history; and its ignored theory; which we need to enable us to <em>act</em> instead of only reacting. And I then highlight some points from my 2013 talk "Toward a Scientific Comprehension and Handling of Problems"; where I developed the parallel between "scientific" and "systemic" by talking about scientific medicine; which bases the handling of diseases on comprehending the anatomy and the physiology that underlies them; and demonstrating that the society's problems too are produced by the pathophysiology of its <em><b>systems</b></em>; and proposing to comprehend and handle the society's problems, the "global issues", in a similarly "scientific" alias "systemic" way.</p> | ||

| + | <p>For a while I contemplated calling the <em><b>systemic innovation</b></em> insight "The systems, stupid!"; which was a paraphrase—or more precisely a <em>correction</em>—of Bill Clinton's 1992 winning electoral slogan "The Economy, stupid!" Economic growth is <em>not</em> "the solution to our problem"; <em><b>systemic innovation</b></em> is! And this (I'll say more about this in a moment)—change of focus from "problems" to <em><b>systems</b></em>—is the winning political agenda <em>for all of us</em>!</p> | ||

| + | <p>At <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>'s 2011 workshop at Stanford University, within the Triple Helix IX international conference, we introduced <em><b>systemic innovation</b></em> as an emerging and necessary or <em>remedial</em> trend; and (the organizational structure developed and represented by) <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em> as (an institutional) <em>enabler</em> of <em><b>systemic innovation</b></em>. We work by creating a <em><b>prototype</b></em> of a <em><b>system</b></em> and organizing a <em><b>transdiscipline</b></em> around it—to update it according to the state-of-the-art insights that its members bring from their disciplines; and to strategically change the corresponding real-life <em><b>systems</b></em> accordingly.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Here too the horizontal line—connecting the fifth and the first of <em><b>five insights</b></em>, which has "action" as label—points to the larger-than-life effects that can be unleashed by the <em>synergy</em> between <em><b>holotopia</b></em>'s insights. It is only when we comprehend our inner <em><b>wholeness</b></em> and the <em><b>ecology of mind</b></em> it necessitates—that we become capable of comprehending and adjusting our <em><b>systems</b></em> accordingly; and vice versa: It is only when our <em><b>systems</b></em> provide us the free time and the peace of mind that we can be able to develop those finer sides of ourselves that those higher reaches of fulfillment or "happiness" so crucially depend. </p> | ||

| + | <p>It is <em>then</em> that <em><b>make things whole</b></em> as action will make perfect sense!</p> | ||

| + | <p>In the manner of simplifying the huge complexity of our world and pointing to remedial action—we may now conclude that <em><b>seeing things whole</b></em> and <em><b>making things whole</b></em> is the way to go.</p> </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Jantsch.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Erich Jantsch]]</center></small></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3" | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md-6">< | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Power structure</h2></div> |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <div class="col-md-3" | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

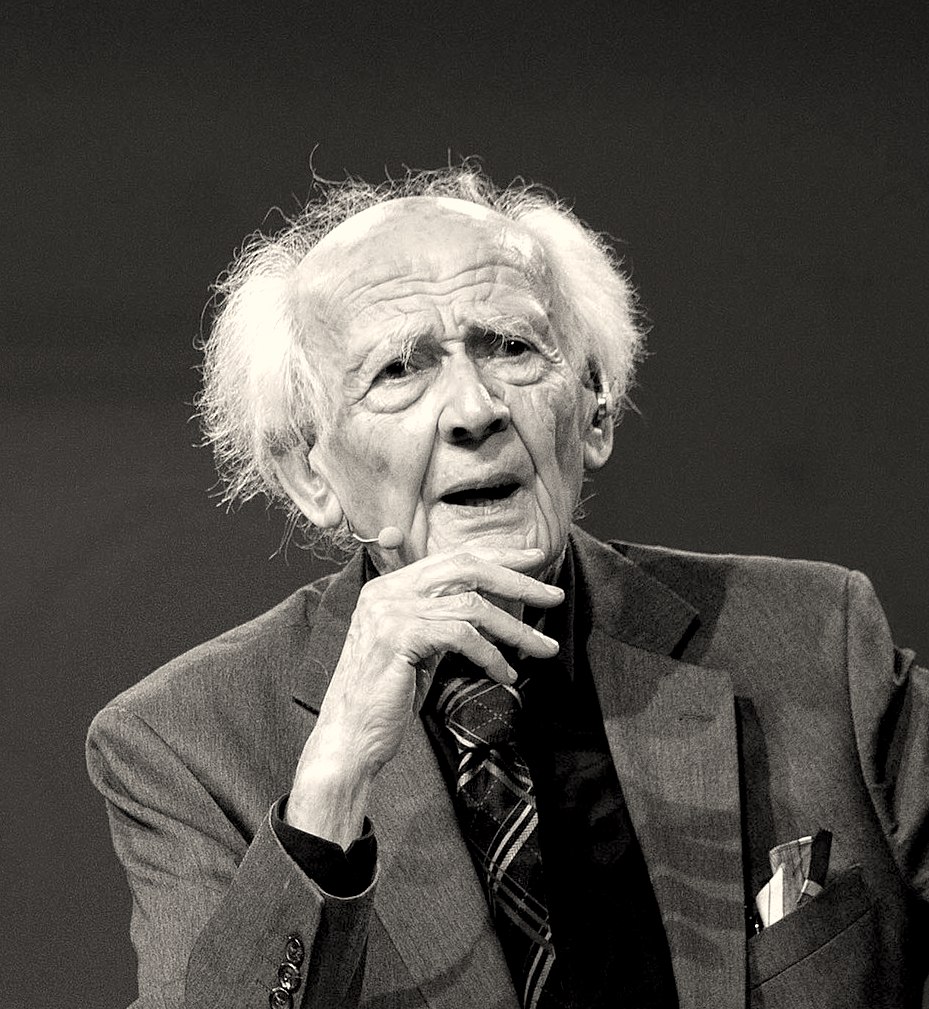

| − | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1"> “Modernity did not make people more cruel; it only invented a way in which cruel things could be done by non-cruel people. Under the sign of modernity, evil does not need any more evil people. Rational people, men and women well riveted into the impersonal, adiaphorized network of modern organization, will do perfectly.”</font> |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <br> |

| − | <p> | + | (Zygmunt Bauman <em>Life in Fragments: Essays in Postmodern Morality</em>, 1995) |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>There is something we <em>must</em>, urgently, comprehend about ourselves; which might <em>alone</em> be the key to reversing the fundamental <em><b>beliefs</b></em> the Enlightenment left us with—<em>and</em> the alarming global trends that resulted from them.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>I am looking at Zygmunt Bauman's book <em>Modernity and the Holocaust</em> on the table here in front of me; which I am re-reading. Which he wrote "to exort fellow social thinkers to consider the relation between the event of the Holocaust and the structure and logic of modern live, to stop viewing the Holocaust as a bizzare and aberrant episode<em>in</em> modern history, and think it through instead as a highly relevant, integral part <em>of</em> that history; 'integral' in the sense of being indispensable for the understanding of what that history was truly about, what it was capable and why—and the sort of society that has emerged from it, and which we all inhabit." In the <em>Liberation</em> book I introduce this theme by talking about Hannah Arendt and her keyword "banality of evil"; to conclude that the "banal evil" is in our time acquiring epic and even monstrous proportions. I am contemplating to coin "geocide" as <em><b>keyword</b></em> to point to what we are about to do—by doing no more than <em>fitting in</em>; by "doing our job"—within the "impersonal, adiaphorized network of modern organization", or <em><b>system</b></em> as I am calling it.</p> |

| − | < | + | <p>But—I'll allow myself to observe, and submit to our <em><b>dialog</b></em>—Bauman lacked a <em><b>methodology</b></em> to bring all the good work that he and his colleagues did to a <em><b>point</b></em>. So I coined <em><b>power structure</b></em> as <em><b>keyword</b></em>—and now use it as a banner erected over a most fertile and uniquely important range on <em><b>knowledge federation</b></em>'s emerging creative frontier; where the deeper causes of our society's ills are comprehended—in connection with our own <em><b>human quality</b></em>, and ethics.</p> |

| − | + | <p>In Chapter Eight of the <em>Liberation</em> book I look deeper—into the <em>nature</em> of the evolution of <em><b>systems</b></em> that's engendered by self-interest and "survival of the fittest"; and show that it results in <em><b>power structure</b></em>—a cancer-like systemic pathology that is destroying both our systems—human <em>and</em> natural—and also us humans. The consequences are sweeping: To be part of the problem—we need to do no more than <em>business as usual</em>; to be accomplices in the geocide—all we need is to <em>not</em> engage; and "do our job"—within the <em><b>systems</b></em> as they have become.</p> | |

| − | </ | + | <p>The political action that distinguishes the <em><b>holotopia</b></em> is profoundly different from what we've been accustomed to; it is <em>Gandhian</em>; it is no longer "us against them"—but <em>all of us</em> against <em><b>power structure</b></em> .</p> |

| − | <p> | + | </div> |

| − | < | + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Bauman.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[Zygmunt Bauman]]</center></small></div> |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | </ | ||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | </div></div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3" | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-6"><h2>Dialog</h2> </div> |

| − | + | <div class="col-md-3"></div> | |

| − | < | + | </div> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </div> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md-3">< | + | <div class="col-md-3"><font size="+1">“As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved.”</font> |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | (David Bohm, <em>Problem and Paradox</em>, an online article.) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-6"><p>When the way we use the <em><b>mind</b></em> is the root of our problems—then this is no longer a problem but a paradox; which turns <em>all</em> our "problems" into paradixes.</p> | |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <h3>The function of the <em><b>dialog</b></em> is to dissolve the paradox.</h3> |

| − | + | <p>The meaning of this keyword is not "conversation", as the word "dialogue" has been commonly used—but derived from the Greek original <em>dialogos</em> (through <em><b>logos</b></em>). The function of the <em><b>dialog</b></em> is to first of all liberate <em><b>logos</b></em>; and to then apply it to rebuild our <em><b>collective mind</b></em>, or "public sphere" as Jürgen Habermans and his colleagues have been calling it; and make <em>democracy</em> possible again; and capable of taking care of its negative trends or "problems".</p> | |

| − | <p> | + | <h3>The <em>dialog</em> is conceived as a practical way to change our <em>collective mind</em>.</h3> |

| − | + | <p>Through judicious use of new media; and use it to <em><b>federate</b></em> a vision; and organize us in action that will empower us to manifest and <em>realize</em> that vision.</p> | |

| − | < | + | <h3>It is through the agency of the <em>dialog</em> that <em>knowledge federation</em> orchestrates the change of our society's 'headlights'.</h3> |

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-3"> [[File:Bohm.jpg]] <br><small><center>[[David Bohm]]</center></small></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 14:46, 11 November 2023

Contents

- 1 Federation through Keywords

- 1.1 We can design scopes by creating keywords.

- 1.2 Keyword creation is a form for linguistic and institutional recycling.

- 1.3 Keywords enable us to 'stand on the shoulders of giants' and see further.

- 1.4 Paradigm

- 1.5 Logos

- 1.6 Design epistemology

- 1.7 Polyscopic methodology

- 1.8 Convenience paradox

- 1.9 Knowledge federation

- 1.10 Systemic innovation

- 1.11 Power structure

- 1.12 Dialog

Federation through Keywords

(Ulrich Beck, The Risk Society and Beyond, 2000)

The key to stepping beyond the "risk society" (where existential risks we can't comprehend or handle lurk in the dark) is to design new ways to see and speak—as the Modernity ideogram suggested. The very approach to information the polyscopic methodology enables is called scope design, where scopes are what determines what we look at and how we see it.

We can design scopes by creating keywords.

Because keywords are defined in the way that's common in mathematics—by convention. When I turn "culture", for instance, into a keyword—I am not saying what culture "really is"; but creating a way of looking at the infinitely complex real thing; and thereby projecting it, as it were, onto a plane—so that we may look at it from a specific side and comprehend it precisely; and I'm inviting you, the reader, to see culture as it's been defined.

Keywords enable us to give old words like "science" and "religion" new meanings; and old institutions a function, and a new life.

Keyword creation is a form for linguistic and institutional recycling.

Often but not always, keywords are adopted from the repertoire of a frontier thinker or an academic field; they then enable us to federate what's been comprehended and seen in our culture's dislocated compartments.

Keywords enable us to 'stand on the shoulders of giants' and see further.

Paradigm

I cannot think of a better illustration of the power of seeing things whole—by designing the way we look—than these wonderful paradoxes I am about to outline; which paradigm as keyword points to; which holotopia as initiative undertakes to overcome.

I use the keyword paradigm informally—to point to a societal and cultural order of things; and when I want to be even more informal—I use elephant as its nickname; to highlight that in a paradigm everything depends on everything else—just as the organs of an elephant do.

The paradigm is the very (social and cultural) "reality" we live in; to which we must conform in order to succeed in anything; because when we don't—and end up failing—we quickly learn that certain things just don't work, and must be avoided. And so willy-nilly—we become part of the paradigm; and let it determine what we consider "realistic", or possible.

So here's a paradox: The paradigm we live in could be arbitrarily dysfunctional, non-sustainable and downright suicidal—and we'll still we'll consider complying to its limitations as (the only) way to "success"; and everything else as impractical or "utopian".

And here's another one: Comprehensive change (of the paradigm as a whole) can be natural and easy—even when attempts to do small and obviously necessary changes have proven impossible; you can't fit an elephant's ear onto a mouse! Paradigms resist change—that goes against the grain of their order of things. And yet changing the paradigm as a whole can be natural and even easy—when the conditions for such a change are ripe.

We live in such a time.

The Liberation book demonstrates that; by developing an analogy between the times and conditions when Galilei was in house arrest—when the Enlightenment was about to spur comprehensive change—and our own time. The Liberation book then proposes—and ignites—a process; by which we'll liberate ourselves from the grip of our paradigm; which, needless to say, needed to be designed; because no matter how hard we may try—we'll never produce the lightbulb by improving the candle!

I use the keyword paradigm also formally, as Thomas Kuhn did—to point to

- a different way to conceive a domain of interest, which

- resolves the reported anomalies and

- opens a new frontier for research and development.

Logos

(René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, 1641)

The natural way to enable the paradigm to change is by changing the way we the people use our minds; as what I just pointed to, the change spurred by the Enlightenment, may illustrate. And it is that very strategy I am inviting you to follow; because the way we use the mind is again ripe for change.

I use the word logos to problematize the way we use the mind; so that instead of taking it for granted, instead of simply using the mind as we're accustomed to, we recognize it as problematic; and begin to pay attention to the very way we use the mind. In the Liberation book I do that by pointing to its historicity; so we may see the way we use the mind as a product of historical circumstances and beliefs; as something that has changed before and can change again.

"In the beginning was logos and logos was with God and logos was God." To the philosophers of antiquity, "logos" was the very principle according to which God created and organized the world; which enables us humans to comprehend the world and live and act in harmony with it, by aligning with it the way we use our minds. How exactly we should go about doing that—the opinions differed; and gave rise to a multitude of philosophical traditions.

But "logos" faired poorly in post-hellenic world; Latin had no equivalent, and the modern languages offered none either. For about a millennium our ancestors believed that logos had been revealed to us humans by God's own son; and recorded in the Bible; and considered further quest of logos to be the deadly sin of pride, and a heresy.

The Englightenment was a revolution.

Which brought human reason to power; and taught us to rely on science-empowered reason to comprehend the world and the life's core themes.

A reason why we must go back to the drawing board, and do as Descartes and his Enlightenment colleagues did—is that they got it all wrong!

They made the error that gave us 'candles' as 'headlights'.

They made indeed two errors, to be precise; when they took it for granted that

- the goal of the pursuit of knowledge, and of science, was to find the "objective" and unchanging truth about "reality"; and that

- this truth is revealed to the mind as the sensation of absolute certainty.

The prospects to make the nature comprehensible in causal terms—as one might comprehend the workings of a clock—retreated every time it appeared to be close to succeeding; the ("indivisible") atom split into one hundred "subatomic particles"; which—when the scientists became able to examine them—turned out to defy not only causality but even the common sense (as J. Robert Oppenheimer pointed out in Uncommon Sense). The presumed 'clockwork of nature' turned out to be like Humpty Dumpty—something that nobody can put together again.

That science—conceived as a collection of specialized disciplines—now occupies the larger-than-life function (of "the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture" as Benjamin Lee Whorf branded it in Language, Thought and Reality) was nobody's conscious design or even intention. For awhile, tradition and science coexisted side by side—the former providing know-what and the latter know-how. But then—right around the mid-nineteenth century, when Darwin entered this scene—science ousted the tradition; and becoe the modernityh's sole arbiter of knowledge.

But science never adjusted itself to this much larger role.

The system of science, as it has emerged from this evolution, has no provisions for updating the system of science. We seem to be simply stuck with a certain way of exploring the world; just as we are stuck with our larger societal paradigm!

Design epistemology

(Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy, 1958.)

You'll easily comprehend the anomaly this third of holotopia's five insights points to, if you just see the way we use the mind (and go about deciding what's true or false and relevant or irrelevant) as the foundation on which the edifice of our culture has been built; which enables some of its parts or sides to grow big and strong (which are supported by this foundation), and abandons others to erosion. As Heisenberg pointed out, what we have as foundation—which our general culture imbibed from 19th century science—prevented cultural evolution to continue; being "so narrow and rigid that it was difficult to find a place in it for many concepts of our language that had always belonged to its very substance, for instance, the concepts of mind, of the human soul or of life." Since "the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided", whatever failed to be founded in this way was considered impossible or unreal. This in particular applied to those parts of our culture in which our ethical sensibilities were rooted, such as religion, which "seemed now more or less only imaginary. [...] The confidence in the scientific method and in rational thinking replaced all other safeguards of the human mind."

Heisenberg then explained how the experience of modern physics constituted a rigorous disproof of this approach to knowledge; and concluded that "one may say that the most important change brought about by its results consists in the dissolution of this rigid frame of concepts of the nineteenth century."

Heisenberg wrote Physics and Philosophy anticipating that the most valuable gift of modern physics to humanity would be a cultural transformation; which would result from the dissolution of the narrow frame.

As an insight, design eistemology shows how a broad and solid foundation can be developed.

By following the approach that is the subject of this proposal.

The design epistemology originated by federating the state-of-the-art epistemological findings; by systematizing and adapting what the giants of science and philosophy have found out—and writing the result as a convention. Here Einstein's "epistemological credo"—which he left us in Autobiographical Notes, his testament or "obituary", is already sufficient:

“I see on the one side the totality of sense experiences and, on the other, the totality of the concepts and propositions that are laid down in books. […] The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system. […] All concepts, even those closest to experience, are from the point of view of logic freely chosen posits, just as is the concept of causality, which was the point of departure for [scientific] inquiry in the first place.”

Modernity ideogram renders design epistemology in a nutshell.

The design epistemology takes the constructivist credo (that we do not discover but construct a "reality picture"; which Einstein expressed succinctly) two evolutionary steps further—by writing it (no longer as a statement about reality, but) as a convention; and assigning to it a purpose.

This foundation is solid or "rigorous".

Because it represents the epistemological state of the art; and because it's a convention. The added purpose can hardly be debated—not only because doing what's necessary to avoid civilizational collapse is hard to argue against; but also because this too is a convention; a different convention, and an altogether different way to knowledge can be created, to suit a different purpose.

A side-effect of this academic update is that it offers us a way to avoid the fragmentation in social sciences; which results when the social scientists disagree whether it's right to see the complex cultural and social reality in one way or another. Here our explicit aim is to see things whole; which translates into the challenge of seeing things in a way that may best reveal their non-whole sides. The simple point here is that when our task is not producing an accurate description of an infinitely complex "reality", but a way to see it that "works" (in the sense of providing us evolutionary guidance)—then the fragmentation is easily diagnosed as part of the problem; and avoided.

Another philosophical stream of thought that the design epistemology embodies is phenomenology; which Einstein pointed to by talking about "the totality of sense experiences" on the one side, and "the totality of the concepts and propositions" on the other side; a point being that human experience (and not "objective reality") is the substance that information can and needs to be founded on, and represent. This allows us to treat not only the sciences—but indeed all cultural traditions and artifacts as 'data'; which in some way or other embody human experience.

This foundation is also broad.

In the sense that it removes completely the narrow frame anomaly; and lets us build knowledge, and culture, on all forms of human experience. By convention, experience does not have any a priori structure; experience is considered to be like the ink blot in a Rorschach test—something to which we freely ascribe interpretation and meaning; as Einstein suggested we should, by formulating his "epistemological credo".

Polyscopic methodology

(Abraham Maslow, Psychology of Science, 1966)

You'll comprehend the anomaly this fourth of holotopia's five insights points to, if you see the method—the category from which it stems—as the toolkit we use to construct truth and meaning; and the culture at large; and consider that—as Maslow pointed out—this method is so specialized that it compels us to be specialized; and choose our themes and set our priorities (not according to their relevance, but) according to what this tool enables us to do.

As an insight, the polyscopic methodology points out that a general-purpose method, which alleviates this problem, can be created by the proposed approach; by federating the findings of giants of science and the techniques developed in the sciences; so as to preserve the advantages of science—and alleviate its limitations.

Design epistemology mandates such a step: When we on the one hand acknowledge that (as far as we know) there is no conclusive truth about reality; and on the other hand, that our very existence depends on information and knowledge—we are bound to be accountable for providing knowledge about the most relevant themes (notably the ones that determine our society's evolutionary course) as well as we are able; and of course to continue to improve both our knowledge and our ways to knowledge.

As long as "reality" and its "objective" descriptions constitute our only reference system—we have no way of evaluating our paradigm critically; all we can do is adapt to it; By building on what I've just told you, polyscopic methodology enables us to develop the realm of ideas as an independent reference system; on truth by convention as foundation; and (the ideas being conceived as abstract simplification)—develop rigorous theories that help us relate not only ideas, but the corresponding elements of our society and culture too; in a moment I'll clarify this by an example.

The polyscopic methodology provides methods for a transdisciplinary approach to knowledge; where patterns, defined as "abstract relationships", have a similar function as mathematical functions do in conventional science—they enable us to formulate general results and theories; including gestalts; suitable method for justifying or 'proving' such results are provided, which design epistemology made possible.

The polyscopic methodology allows us to define what information needs to be like; and in this way exercise the accountability I pointed to when I talked about the analogy with computer programming, and the related methodologies.

Convenience paradox

(Aurelio Peccei, One Hundred Pages for the Future, 1981)

You'll appreciate the importance of the anomaly the convenience paradox—the fifth of holotopia's five insights—is pointing to, if you consider it in the context of the need to change course by shifting the current focus of our striving from material production and consumption to humanistic and cultural pursuits and values; the need of which everyone who has studied our evolutionary challenges and opportunities seems to have agreed on; which with new information technology—you may now hear straight from the horse's mouth!

And you'll see the anomaly itself if you reflect for a moment how Heisenberg described the narrow frame (the way to see and comprehend the world that defined our cultural paradigm, which is now ripe for change); where "the concept of reality applied to the things or events that we could perceive by our senses or that could be observed by means of the refined tools that technical science had provided"; and notice that this way to conceive of "reality" leaves in the dark one whole dimension of reality—time; and one might say, one whole half or side of space too—its inner or embodied side; so that the only thing we can perceive and comprehend and work with is convenience—whereby we seek, and reach out to get, what feels attractive or fun, and vice versa.

Convenience leaves in the dark a myriad possibilities for developing human quality.

Which is what culture is all about by definition.

As an insight, and a proof-of-concept result of applying polyscopic methodology, and as a quintessential information holon—the convenience paradox points to the sheer absurdity of convenience as value; and to a myriad possibilities to radically improve the human condition through cultural means.

Convenience paradox is point of inception of an entirely new culture.

The Liberation book can be read in several different ways; but one of the more interesting ones is undoubtedly to see it as a roadmap to a whole human condition; where the first five chapters describe the inner wholeness; and the remaining five chapters the outer wholeness; and the overall effect is to see that those two are closely interdependent and indeed undistinguishable; and that wholeness indeed is the value or 'destination' we'll most naturally pursue—as soon as we use real light to see and navigate the world.

Then you may also see the Liberation book as a template for comprehending and evaluating things and ideas—notably the culture-transformative memes—(not by fitting them into the existing paradigm, where they don't fit in by definition, but) by fitting them into the emerging order of things; by seeing them as part and parcel of an emerging whole human condition; as portrayed by holotopia, or the elephant.

This template is produced by federating two insights reached by Buddhadasa—Thailand's holy man and Buddhism reformer.

By seeing them as necessary elements of (our quest for) wholeness. The first of Buddhadasa's insights, which I call in the book origination of conditioning, turns our conventional "pursuit of happiness" (conceived as pursuit of convenience) on its head! And the second, that wholeness demands that we liberate ourselves from self-centeredness, which he saw as the shared trait of Buddhism with the great world religions; which the book's subtitle "Religion beyond Belief" points to. The point here is to comprehend why self-centeredness and convenience only appear to us as valuable when we see the way in the light of a pair of candles; and thoroughly disastrous when we see things whole. I feel tempted to improvise now, and tease you a bit; so here's something we may take up in our dialog; the history of religion (seen as a function in culture—to liberate us from self-centeredness) may now be seen as having three phases; where first

- belief was used to coerce people to do the right thing; and then

- beliefs of tradition were dispersed and new beliefs, of materialism introduced; and the people ended up doing the wrong thing; until finally

- we developed the ability to see things whole; and see religion (understood as that side of culture that develops human quality and eliminates self-centeredness and various defects it produces) as necessary for making things whole.

Knowledge federation

(Doug Engelbart, "Dreaming of the Future*, BYTE Magazine, 1995)

The pivotal category from which knowledge federation—the second of five insights—stems is "communication"; which here means specifically the collection of processes by which we the people communicate; enabled by information technology. You'll easily see the anomaly this insight points to if you think of knowledge federation as the radical alternative to publishing or broadcasting—the process that was enabled by the earlier technological revolution, the printing press; and think how much the belief that when something is published it is also "known"—which still marks the academic culture and in particular its process—is removed from reality.

What will help you complete the analogy between our present processes of communication and the candle headlights is the fact that the "digital technology"—the interactive, network-interconnected digital media, which you and I use to write emails and browse the Web—has been created, by Doug Engelbart and his SRI-based team, as the enabling technology for an entirely different process; which we call knowledge federation.

This Incredible History of Doug Engelbart, as I ended up calling it, is the best story I know of to illustrate the opportunities that are germane in the emerging paradigm and the obstacles we have to face. I wrote it up as a book manuscript draft; and then left it to be published as the second book in the holotopia series; and wrote a very brief version in Chapter Seven of the Liberation book, which has "Liberation of Society" as title. The fact that Engelbart was unable to communicate his vision to the Silicon Valley academia and businesses—no matter how hard he tried, even after he was widely recognized as the giant behind "the revolution in the Valley"—is the most vivid illustration of exactly the core issue I've been telling you about; how much we are stuck in "reality" of the present paradigm—without conceptual and cognitive tool, or even the time to think deeply enough to comprehend things in new ways.

I use collective mind as keyword to pinpoint the gist of Engelbart's vision; which is that the technology that Engelbart envisioned and created is the enabling technology for the capability we need—the capability to handle complex and urgent problems; because it constitutes a 'collective nervous system' that enables us develop entirely new processes in communication—and think and act and inform each other in a similar way in which the cells of an evolutionarily evolved organism co-create meaning and communicate. Imagine what would happen if your own cells used your nervous system to merely broadcast data—and you'll have no difficulty comprehending the anomaly that knowledge federation undertakes to resolve.

Our 2010 workshop—where we began to self-organize as a transdiscipline—was called "Self-Organizing Collective Mind". Prior to this workshop I spent the school year on sabbatical in San Francisco Bay Area; and strengthened the ties with the R & D community that grew around Engelbart called Program for the Future, which Mei Lin Fung initiated in Palo Alto to continue and complete the work on implementing Engelbart's vision; and of course with Engelbart himself. At the University of Oslo Computer Science Department I later taught a doctoral course about Engelbart's legacy—to research it thoroughly, and develop ways to communicate it.

As an insight, knowledge federation stands for the fact that a radically better communication is both necessary and possible; exactly the sort of quantum leap that the Modernity ideogram is pointing to. We made this possibility transparent by developing a portfolio of prototypes—real-life models of socio-technical systems in communication; which I'll here illustrate by our Tesla and the Nature of Creativity 2015 prototype as canonical example; where the result of an academic researcher, Dejan Raković of the University of Belgrade, has been federated in three phases; where

- the first phase made the result comprehensible to a larger audience; by turning his research into a multimedia object (this was done by knowledge federation communication design team); where its main points were extracted and made comprehensible by explanatory diagrams or ideograms; and further explained by placing on them links to recorded interviews with the author;

- the second phase made the result known and at the same time discussed in space—by staging a televised high-profile dialog at Sava Center Belgrade;

- the third phase organized a social process around the result (by using DebateGraph); a sort of updated and widely extended "peer reviews", through which global experts were able to comment on it, link it with other results and so on.