Holotopia

Contents

HOLOTOPIA

An Actionable Strategy

Imagine...

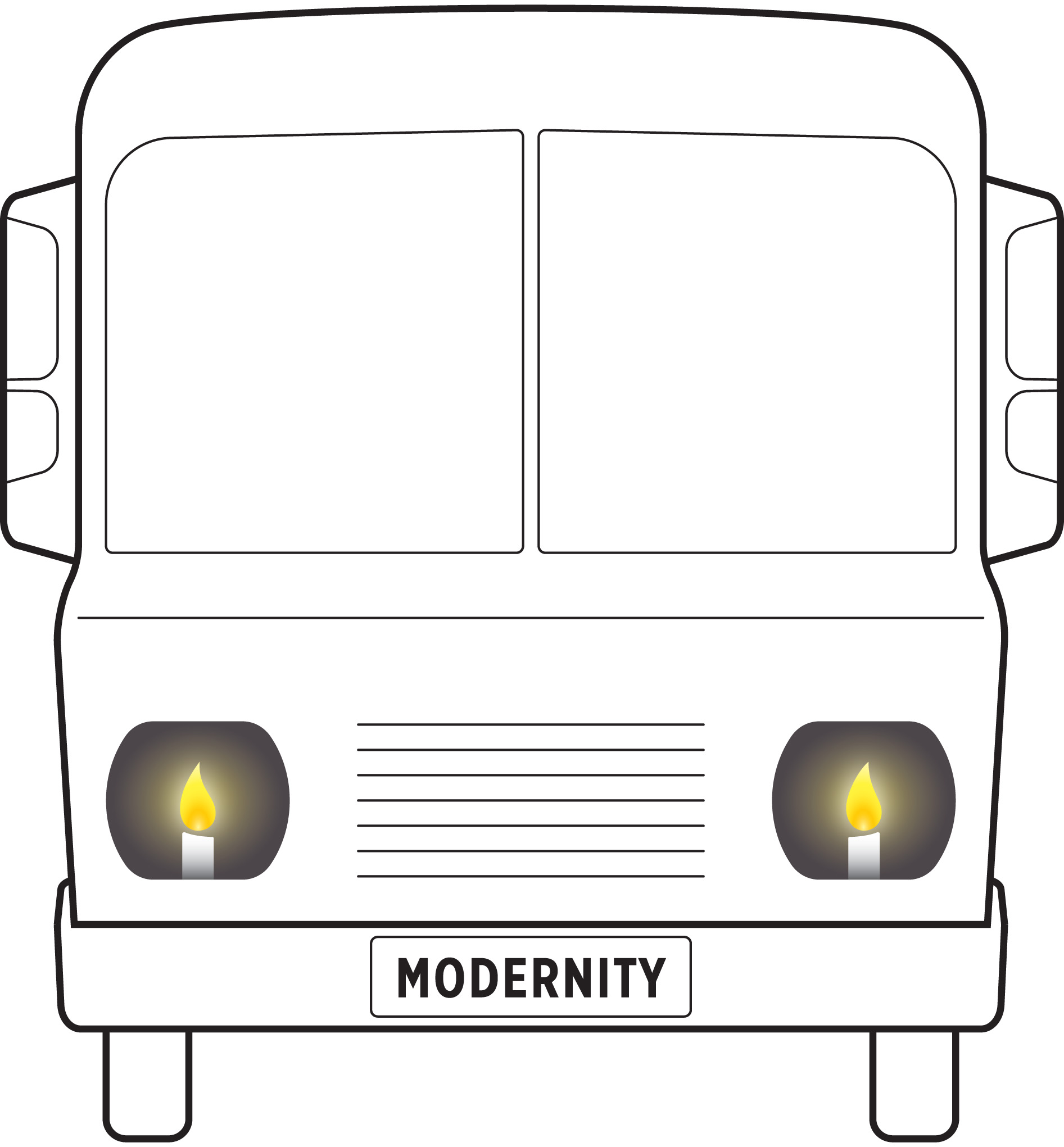

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

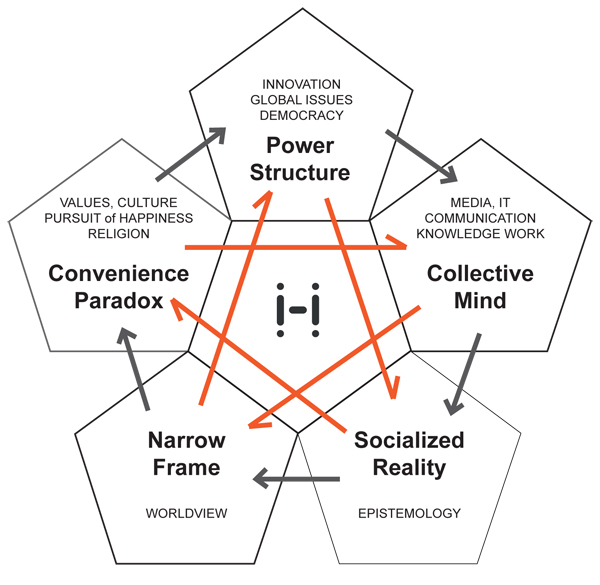

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Our proposal

The core of our knowledge federation proposal is to change the relationship we have with information.

What is our relationship with information presently like?

Here is how Neil Postman described it:

"The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it."

What would information and our handling of information be like, if we treated them as we treat other human-made things—if we adapted them to the purposes that need to be served?

By what methods, what social processes, and by whom would information be created? What new information formats would emerge, and supplement or replace the traditional books and articles? How would information technology be adapted and applied? What would public informing be like? And academic communication, and education?

The substance of our proposal is a complete prototype of knowledge federation, where initial answers to relevant questions are proposed, and in part implemented in practice.

Our call to action is to institutionalize and develop knowledge federation as an academic field, and a real-life praxis (informed practice).

Our purpose is to restore agency to information, and power to knowledge.

All elements in our proposal are deliberately left unfinished, rendered as a collection of prototypes. Think of them as composing a 'cardboard model of a city', and a 'construction site'. By sharing them we are not making a case for a specific 'city'—but for 'architecture' as an academic field, and a real-life praxis.

A proof of concept application

The Club of Rome's assessment of the situation we are in, provided us with a benchmark challenge for putting the proposed ideas to a test.

Four decades ago—based on a decade of this global think tank's research into the future prospects of mankind, in a book titled "One Hundred Pages for the Future"—Aurelio Peccei issued the following call to action:

"It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course."

Peccei also specified what needed to be done to "change course":

"The future will either be an inspired product of a great cultural revival, or there will be no future."

This conclusion, that we are in a state of crisis that has cultural roots and must be handled accordingly, Peccei shared with a number of twentieth century thinkers. Arne Næss, Norway's esteemed philosopher, reached it on different grounds, and called it "deep ecology".

In "Human Quality", Peccei explained his call to action:

"Let me recapitulate what seems to me the crucial question at this point of the human venture. Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it. However, the business of human life has become so complicated that he is culturally unprepared even to understand his new position clearly. As a consequence, his current predicament is not only worsening but, with the accelerated tempo of events, may become decidedly catastrophic in a not too distant future. The downward trend of human fortunes can be countered and reversed only by the advent of a new humanism essentially based on and aiming at man’s cultural development, that is, a substantial improvement in human quality throughout the world."

The Club of Rome insisted that lasting solutions would not be found by focusing on specific problems, but by transforming the condition from which they all stem, which they called "problematique".

A vision

Holotopia is a vision of a future that becomes accessible when proper 'light' has been 'turned on'.

Since Thomas More coined this term and described the first utopia, a number of visions of an ideal but non-existing social and cultural order of things have been proposed. In view of adverse and contrasting realities, the word "utopia" acquired the negative meaning of an unrealizable fancy.

As the optimism regarding our future waned, apocalyptic or "dystopian" visions became common. The "protopias" were offered as a compromise, where the focus is on smaller but practically realizable improvements.

The holotopia is different in spirit from them all. It is a more attractive than the futures the utopias projected—whose authors either lacked the information to see what was possible, or lived in the times when the resources we have did not exist. And yet the holotopia is readily attainable—because we already have the information and other resources that are needed for its fulfillment.

The holotopia vision is made concrete in terms of five insights, as explained below.

A principle

What do we need to do to "change course" toward holotopia?

The five insights point to a simple principle or rule of thumb—making things whole.

This principle is suggested by holotopia's name. And also by the Modernity ideogram. Instead of reifying our institutions and professions, and merely acting in them competitively to improve "our own" situation or condition, we consider ourselves and what we do as functional elements in a larger system of systems; and we self-organize, and act, as it may best suit the wholeness of it all.

Imagine if academic and other knowledge-workers collaborated to serve and develop planetary wholeness – what magnitude of benefits would result!

A method

"The arguments posed in the preceding pages", Peccei summarized in One Hundred Pages for the Future, "point out several things, of which one of the most important is that our generations seem to have lost the sense of the whole."

To make things whole—we must see things whole!

To highlight that the knowledge federation methodology described and implemented in the proposed prototype affords that very capability, to see things whole, in the context of the holotopia we refer to it by the pseudonym holoscope.

While the characteristics of the holoscope—the design choices or design patterns, how they follow from published insights and why they are necessary for 'illuminating the way'—will become obvious in the course of this presentation, one of them must be made clear from the start.

To see things whole, we must look at all sides.

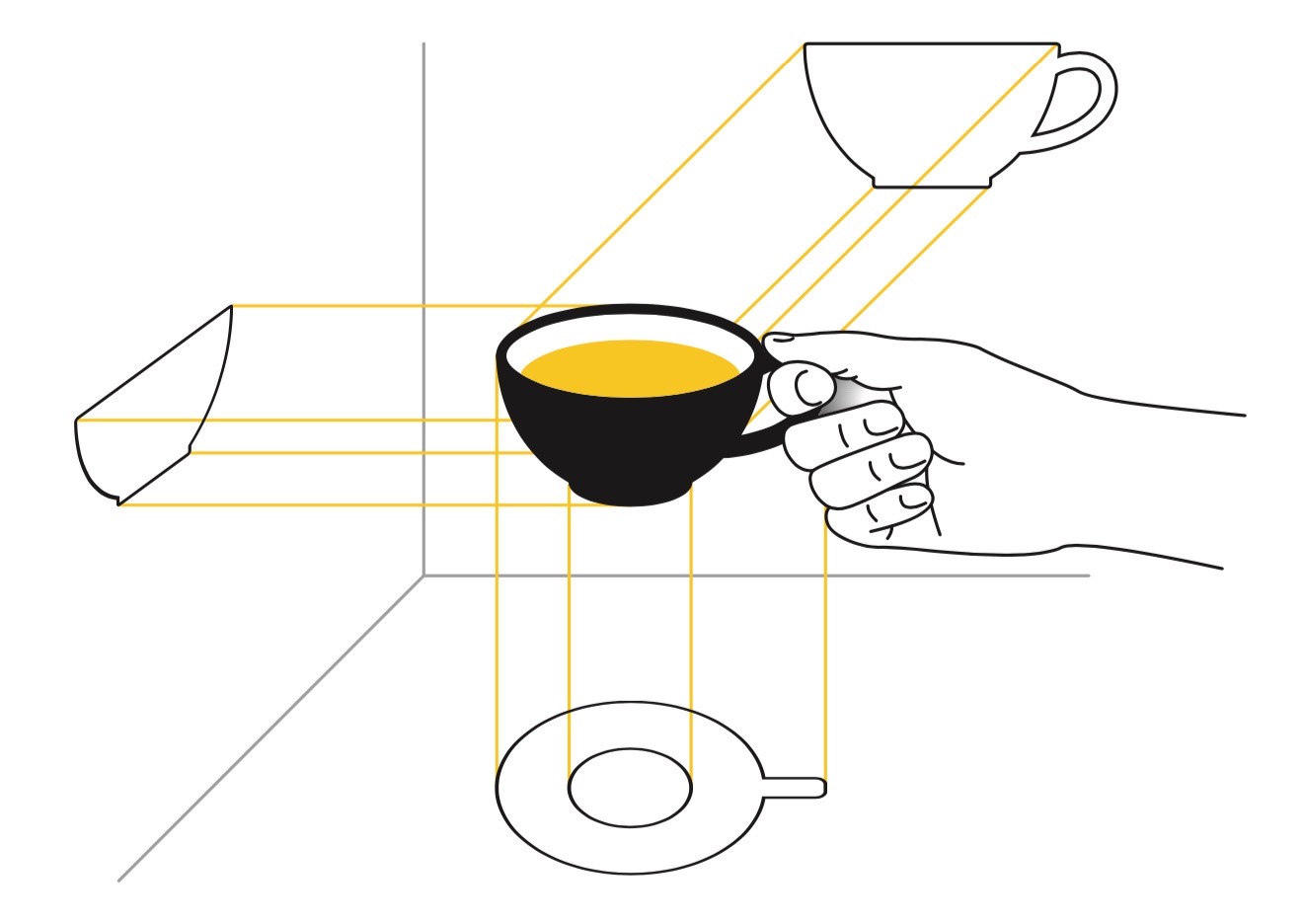

The holoscope distinguishes itself by allowing for multiple ways of looking at a theme or issue, which are called scopes. The scopes and the resulting views have similar meaning and role as projections do in technical drawing. The views that show the entire whole from a certain angle are called aspects.

This modernization of our handling of information—distinguished by purposeful, free and informed creation of the ways in which we look at a theme or issue—has become necessary in our situation, suggests the bus with candle headlights. But it also presents a challenge to the reader—to bear in mind that the resulting views are not "reality pictures", contending for that status with one other and with our conventional ones.

In the holoscope, the legitimacy and the peaceful coexistence of multiple ways to look at a theme is axiomatic.

To liberate our worldview from the inherited concepts and methods and allow for deliberate choice of scopes, we used the scientific method as venture point—and modified it by taking recourse to insights reached in 20th century science and philosophy.

Science gave us new ways to look at the world: The telescope and the microscope enabled us to see the things that are too distant or too small to be seen by the naked eye, and our vision expanded beyond bounds. But science had the tendency to keep us focused on things that were either too distant or too small to be relevant—compared to all those large things or issues nearby, which now demand our attention. The holoscope is conceived as a way to look at the world that helps us see any chosen thing or theme as a whole—from all sides; and in proportion.

A way of looking or scope—which reveals a structural problem, and helps us reach a correct assessment of an object of study or situation—is a new kind of result that is made possible by (the general-purpose science that is modeled by) the holoscope.

We will continue to use the conventional way of speaking and say that something is as stated, that X is Y—although it would be more accurate to say that X can or needs to be perceived (also) as Y. The views we offer are accompanied by an invitation to genuinely try to look at the theme at hand in a certain specific way (to use the offered scopes); and to do that collaboratively, in a dialog.

Five insights

Scope

What is wrong with our present "course"? In what ways does it need to be changed? What benefits will result?

We apply the holoscope and illuminate five pivotal themes, which determine the "course":

- Innovation—the way we use our ability to create, and induce change

- Communication—the social process, enabled by technology, by which information is handled

- Epistemology—the fundamental assumptions we use to create truth and meaning; which determine "the relationship we have with information"

- Method—the way in which truth and meaning are constructed in everyday life; or "the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it"

- Values—the way we "pursue happiness"; our values determine the course

In each case, we see a structural defect, which led to perceived problems. We demonstrate practical ways, partly implemented as prototypes, in which those structural defects can be remedied. We see that their removal naturally leads to improvements that are well beyond the elimination of problems.

The holotopia vision results.

In the spirit of the holoscope, we here only summarize the five insights—and provide evidence and details separately.

Scope

What might constitute "a way to change course"?

"Man has acquired such decisive power that his future depends essentially on how he will use it", observed Peccei. Imagine if some malevolent entity, perhaps an insane dictator, took control over that power!

The power structure insight is that no dictator is needed.

While the nature of the power structure will become clear as we go along, imagine it, to begin with, as our institutions; or more accurately, as the systems in which we live and work (which we simply call systems).

Notice that systems have an immense power—over us, because we have to adapt to them to be able to live and work; and over our environment, because by organizing us and using us in certain specific ways, they decide what the effects of our work will be.

The power structure determines whether the effects of our efforts will be problems, or solutions.

Diagnosis

How suitable are the systems in which we live and work for their all-important role?

Evidence shows that the power structure wastes a lion's share of our resources. And that it either causes problems, or makes us incapable of solving them.

The root cause of this malady is in the way systems evolve.

Survival of the fittest favors the systems that are predatory, not those that are useful.

This excerpt from Joel Bakan's documentary "The Corporation" (which Bakan as a law professor created to federate an insight he considered essential) explains how the most powerful institution on our planet evolved to be a perfect "externalizing machine" ("externalizing" means maximizing profits by letting someone else bear the costs, notably the people and the environment), just as the shark evolved to be a perfect predator. This scene from Sidney Pollack's 1969 film "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" will illustrate how the power structure affects our own condition.

The systems provide an ecology, which in the long run shapes our values and "human quality". They have the power to socialize us in ways that suit their survival interests. "The business of business is business"; if our business is to succeed in competition, we must act in ways that lead to that effect. To the system it makes no difference whether we bend and comply, or get replaced.

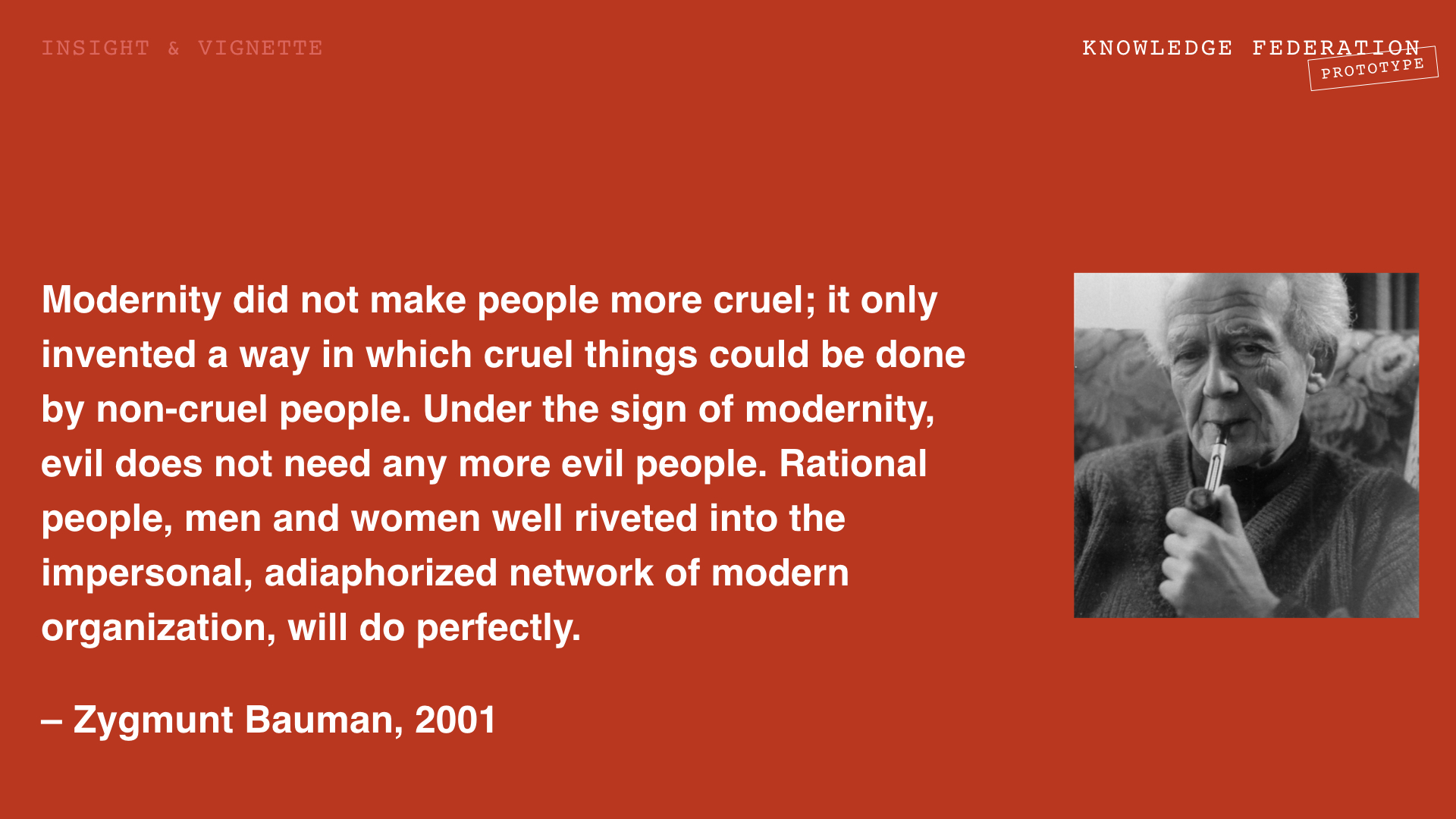

A consequence, Zygmunt Bauman diagnosed, is that bad intentions are no longer needed for bad things to happen. Through socialization, the power structure can co-opt our duty and commitment, and even heroism and honor.

Bauman's insight that even the holocaust was a consequence and a special case, however extreme, of the power structure, calls for careful contemplation: Even the concentration camp employees, Bauman argued, were only "doing their job"—in a system whose character and purpose was beyond their field of vision, and power to change.

While our focus is on the power structures of the past, we are committing—in all innocence, by acting only through the power structures we are part of—the greatest massive crime in human history.

Our children may not have a livable planet to live on.

Not because someone broke the rules—but because we follow them.

Remedy

The fact that we will not solve our problems unless we develop the capability to update our systems has not remained unnoticed.

The very first step that the The Club of Rome's founders made after its inception, in 1968, was to convene a team of experts, in Bellagio, Italy, to develop a suitable methodology. They gave making things whole on the scale of socio-technical systems the name "systemic innovation"—and we adopted that as one of our keywords.

The work and the conclusions of this team were based on results in the systems sciences. In the year 2000, in "Guided Evolution of society", systems scientist Béla H. Bánáthy surveyed relevant research, and concluded in a true holotopian tone:

We are the first generation of our species that has the privilege, the opportunity and the burden of responsibility to engage in the process of our own evolution. We are indeed chosen people. We now have the knowledge available to us and we have the power of human and social potential that is required to initiate a new and historical social function: conscious evolution. But we can fulfill this function only if we develop evolutionary competence by evolutionary learning and acquire the will and determination to engage in conscious evolution. These two are core requirements, because what evolution did for us up to now we have to learn to do for ourselves by guiding our own evolution.

In 2010 Knowledge Federation began to self-organize to enable progress on this frontier.

The method we use is simple: We create a prototype of a system, and a transdisciplinary community and project around it to update it continuously. The insights in participating disciplines can in this way have real or systemic effects.

Our very first prototype of this kind, the Barcelona Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism in 2011, was of a public informing that identifies systemic causes and proposes corresponding solutions (by involving academic and other experts) of perceived problems (reported by people directly, through citizen journalism).

A year later we created The Game-Changing Game as a generic way to change systems—and hence as a "practical way to craft the future"; and based on it The Club of Zagreb, an update of The Club of Rome.

Each of about forty prototypes in our portfolio is a result of applying systemic innovation in a specific domain. Each of them is conceived in terms of design patterns—problem-solution pairs, ready to be adapted to other applications and domains.

The Collaborology prototype, in education, will illustrate the advantages of systemic innovation.

An education that prepares us only for traditional professions, once in a lifetime, is an obvious obstacle to systemic change. Collaborology implements an education that is in every sense flexible (self-guided, life-long...), and in an emerging area of interest (collaborative knowledge work, as enabled by new technology). By being collaboratively created itself (Collaborology is created and taught by a network of international experts, and offered to learners world-wide), the economies of scale result that dramatically reduce effort. This in addition provides a sustainable business model for developing and disseminating up-to-date knowledge in any domain of interest. By conceiving the course as a design project, where everyone collaborates on co-creating the learning resources, the students get a chance to exercise and demonstrate "human quality". This in addition gives the students an essential role in the resulting 'knowledge-work ecosystem' (as 'bacteria', extracting 'nutrients') .

Scope

We have just seen that our key evolutionary task is to make institutions whole.

Where—with what institution or system—shall we begin?

The handling of information, or metaphorically our society's 'headlights', suggests itself as the answer for two reasons.

One of them is obvious: If information and not competition will be our guide, then our information will need to be different.

In his 1948 seminal "Cybernetics", Norbert Wiener pointed to another reason: In social systems, communication—which turns a collection of independent individual into a coherently functioning entity— is in effect the system. It is the communication system that determines how the system as a whole will behave. Wiener made that point by talking about the colonies of ants and bees. Cybernetics has shown—as its main point, and title theme—that "the tie between information and action" has an all-important role, which determines (Wiener used the technical keyword "homeostasis", but let us here use this more contemporary one) the system's sustainability. The full title of Wiener's book was "Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine". To be able to correct their behavior and maintain inner and outer balance, to be able to "change course" when the circumstances demand that, to be able to continue living and adapting and evolving—a system must have suitable communication-and-control.

Diagnosis

Presently, our core systems, and with our civilization as a whole, do not have that.

The tie between information and action has been severed, Wiener too observed.

Our society's communication-and-control is broken; it needs to be restored.

To make that point, Wiener cited an earlier work, Vannevar Bush's 1945 article "As We May Think", where Bush pointed to the broken connection between scientific information, and public awareness and policy. Bush urged the scientists to make the task of revising their communication their next highest priority—the World War Two having just been won.

These calls to action remained without effect.

"As long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved," observed David Bohm. Wiener too entrusted his insight to the communication whose tie with action had been severed. We have assembled a collection of examples of similarly important academic results that shared a similar fate—to illustrate a general phenomenon we call Wiener's paradox.

As long as the connection between communication and action is broken—the academic results that challenge the present "course" or point to a new one will be ignored.

An academic researcher may feel disheartened to see so many best ideas of our best minds ignored. What's the use of all the hard work and publishing—when even the most basic insights from our field, which are necessary for understanding the relevance of the nuances we are working on—have not been communicated to the public?

This sentiment is, however, transformed to holotopian optimism, as soon we look at the vast creative frontier that is opening up. We are empowered to, we are indeed obliged to reinvent the academic system that determines how we collaborate, and what the effects of our work will be.

And optimism will turn into enthusiasm, when we consider also this ignored fact:

The network-interconnected interactive digital media technology, which is in common use, was created to enable a new paradigm on that frontier.

The 'lightbulb' has already been created—for the purpose of providing our society the vision it needs.

We, however, still use 'candles'.

Vannevar Bush pointed to this new paradigm, which we call collective mind, already in his title, "As We May Think". His point was that "thinking" means making associations or "connecting the dots". And that given our vast volumes of information—technology and processes must be devised to enable us to "connect the dots" or think together, as a single mind does. He described a prototype system called "memex", based on microfilm as technology.

Douglas Engelbart took Bush's idea in a whole new direction—by observing (in 1951!) that when each of us humans are connected to a personal digital device through an interactive interface, and when those devices are connected into a network—then the overall result is that we are interconnected as the cells in a human organism are, by the organism's nervous system.

All earlier innovations in this area—from the clay tablets to the printing press—required that a physical medium with the message be physically transported.

This new technology allows us to "create, integrate and apply knowledge" concurrently, as cells in the human organism do.

We can develop insights and solutions together.

We can be "collectively intelligent".

Engelbart conceived this new technology to enable us, and our systems, to tackle the "complexity times urgency" of our problems, which he saw as growing at an accelerated rate.

But this, Engelbart observed, requires that we think differently; It requires that we use the technology to make systems whole.

This three minute video clip, which we dubbed "Doug Engelbart's Last Wish", will give us a chance to pause and reflect; see what all this practically means. Think about the prospects of improving our institutional and civilizational collective minds. Imagine "the effects of getting 5% better", Engelbart commented with a smile. Then he put his fingertips on his forehead and looked up: "I've always imagined that the potential was... large..." The improvement that is both necessary and possible is not just stupendously large; it is qualitative—from communication that doesn't work, and systems that don't work, to ones that do.

To Engelbart's dismay, our new "collective nervous system" ended up being used to do no better than make the old processes and systems more efficient. The ones that evolved through the centuries of use of the printing press. The ones that broadcast data, and overwhelm us with information.

Anthony Giddens pointed to the effect our dazzled and confused collective mind had on culture; and on "human quality".

Our sense of meaning having been drowned in an overload of data, in a reality that's become too complex to comprehend—we resort to "ontological security". We find meaning in learning a profession, and performing in it competitively.

Information, and the way we handle it, bind us to power structure.

Remedy

How can we repair the severed tie between communication and action?

How can we change our collective mind—as our situation demands, and our technology enables?

Engelbart left us a simple answer: Bootstrapping.

Writing what needs to be done will not lead to solution (the tie between information and action being broken). Bootstrapping demands that we self-organize, and act, as it may best serve to restore systems to wholeness.

Bootstrapping means that we either create functional systems with the material of our own minds and bodies, or help others do that.

The Knowledge Federation transdiscipline was conceived by an act of bootstrapping, to enable bootstrapping.

What we are calling knowledge federation is an umbrella term for a variety of activities and social processes that together comprise a well-functioning collective mind. Their development and dissemination obviously requires a new body of knowledge, and a new institution.

The critical task, however, is to weave the state of the art knowledge and technology directly into systems.

Paddy Coulter, Mei Lin Fung and David Price speaking at our "An Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism" workshop in Barcelona

We use the above triplet of photos ideographically, to highlight that we are doing that.

In 2008, when Knowledge Federation had its inaugural meeting, two closely related initiatives were formed: Program for the Future (a Silicon Valley-based initiative to continue and complete "Doug Engelbart's unfinished revolution") and Global Sensemaking (an international community of researchers and developers of collective mind technology and processes). The featured participants of our 2011 workshop in Barcelona, where our public informing prototype was created, are Paddy Coulter (the Director of Oxford Global Media and Fellow of Green College Oxford, formerly the Director of Oxford University's Reuter Program in Journalism) Mei Lin Fung (the founder of Program for the Future) and David Price (who co-founded both the Global Sensemaking R & D community and Debategraph—which is now the leading global platform for collective thinking).

Other prototypes contributed other design patterns for restoring the severed tie between information and action. The Tesla and the Nature of Creativity TNC2015 prototype showed how to federate a research result that has general interest for the public, which is written in an academic vernacular (of quantum physics). The first phase of this prototype, where the author collaborated with our communication design team, turned the academic article into a multimedia object, with intuitive, metaphorical diagrams and explanatory interviews with the author. The second phase was a high-profile live streamed dialog, where the result was announced and discussed. The third phase was online collective thinking about the result, by using Debategraph.

The Lighthouse 2016 prototype is conceived as a direct remedy for the Wiener's paradox, created for and with the International Society for the Systems Sciences. This prototype models a system by which an academic community can federate an answer to a socially relevant question (combine their resources in making it reliable and clear, and communicate it to the public).

The question in this case was whether can rely on "free competition" to guide the evolution and the operation of our systems; or whether the alternative—the information developed in the systems sciences—should be used.

Scope

"Act like as if you loved your children above all else",Greta Thunberg, representing her generation, told the political leaders at Davos. Of course political leaders love their children—don't we all? But Greta was asking them to 'hit the brakes'; and when the 'bus' they are believed to be 'driving' is inspected, it becomes clear that its 'brakes' too are dysfunctional.

The job of a political leader is to keep 'the bus on course' (the economy growing) for yet another four years. Changing 'course', by changing the system, is beyond what politicians can do, or even imagine doing.

The COVID-19 pandemic may demand systemic changes now.

Who—what institution or system—will lead us through our unprecedentedly large creative challenges?

Both Erich Jantsch and Doug Engelbart believed "the university" would have to be the answer; and they made their appeals accordingly. But the universities ignored them.

Why?

There are evidently two ways in which the social role of the university can be perceived: The role the university must fulfill (claim the new-paradigm thinkers) if our civilization is to continue; and the role that we, academic professionals, consider ourselves to be in.

We shall see that the roots of this dichotomy are in our institution's history. And that the key to resolving it is to admit the historicity of the academic ethos—as Stephan Toulmin pointed out in "Return to Reason", and we summarized and commented in this blog post.

We shall not argue that the contemporary-academic self-perception needs to change. Our point will be that, on the contrary, acting in accord with the way in which we, academic people perceive our social role requires a fundamental change—of the kind that can ignite a more comprehensive social and cultural change. In other words, we shall see that the academic tradition is in a similar situation today as it was at the time when Galilei was in house arrest.

We shall see why changing the relationship we have with information, which is presently in academia's custody, is mandated on both fundamental and pragmatic grounds.

We shall see why changing the relationship we have with information is the natural and easy "way to change course"—being something that we, academic professionals, have to do anyway.

Diagnosis

This diagnosis will be an assessment of the contemporary university's situation, and its causes.

We will come to understand the university's situation as a consequence of three events or points in this institution's evolution. The first two will allow us to understand the origins of academic self-perception; the third to see why this self-perception demands that we change the relationship we have with information.

The first event is the university institution's point of inception, within the antique philosophical tradition, and concretely as Plato's Academy. John Marenbon described the mindset of the Academy as follows (in "Early Medieval Philosophy"; the boldface emphasis is ours):

Plato is justly regarded as a philosopher (and the earliest one whose works survive in quantity) because his method, for the most part, was to proceed to his conclusions by rational argument based on premises self-evident from observation, experience and thought. For him, it was the mark of a philosopher to move from the particular to the general, from the perceptions of the senses to the abstract knowledge of the mind. Where the ordinary man would be content, for instance, to observe instances of virtue, the philosopher asks himself about the nature of virtue-in-itself, by which all those instances are virtuous. Plato did not develop a single, coherent theory about universals (for example, Virtue, Man, the Good, as opposed to an instance of virtue, a particular man, a particular good thing); but the Ideas, as he called universals, play a fundamental part in most of his thought and, through all his different treatments of them, one tendency remains constant. The Ideas are considered to exist in reality; and the particular things which can be perceived by the senses are held to depend, in some way, on the Ideas for being what they are. One of the reasons why Plato came to this conclusion and attached so much importance to it lies in a preconception which he inherited from his predecessors. Whatever really is, they argued, must be changeless; otherwise it is not something, but is always becoming something else. All the objects which are perceived by the senses can be shown to be capable of change: what, then, really is? Plato could answer confidently that the Ideas were unchanging and unchangeable, and so really were. Consequently, they—and not the world of changing particulars—were the object of true knowledge. The philosopher, by his ascent from the particular to the general, discovers not facts about the objects perceptible to the senses, but a new world of true, changeless being.

The highlights we made in Marenbon's text allow us to formulate the first point of this diagnosis:

The university has its roots in a philosophical tradition whose goal was to pursue true knowledge—assumed to be the knowledge of unchanging and unchangeable reality.

Any rational method must ultimately rest on premises or axioms that are not rationally provable, which are considered "self-evident from observation, experience and thought". The fundamental axiom here was that true knowledge is "the knowledge of reality". The only question was how that knowledge was to be reached.

Subsequent developments determined the way in which this question is now answered—and hence the academic ethos, and institutional structure.

It was Aristotle, Plato's star student, who applied the Academia's rational method to a variety of themes. The recovery of Aristotle was a milestone in the intellectual history of the Middle Ages; but the Scholastics used his method to argue the truth of the Scripture.

Aristotle's physics was common sense: Objects tend to fall down; heavier objects tend to fall faster. Galilei proved him wrong by throwing stones of varying size from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. He devised a mathematical formula, by which the speed of a falling object could be calculated exactly. To the human mind about to become modern, Galilei (and the forefathers of science he here represents) demonstrated the superiority of the scientific way to truth.

We may now interpret Toulmin's above cryptic observations as follows: How could the rational method of Galilei and Newton, which was conceived for exploring the questions that "had no day-to-day relevance to human welfare"—assume such an all-important role and become the model and the foundation for pursuing knowledge in general?

As the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest might suggest, when science was taking shape, the Church and the tradition had the prerogative of determining how people thought and behaved—which they held onto most firmly! The scientists were allowed to pursue their interests because they "had no day-to-day relevance to human welfare". But the educated, modern mind considered the fundamental axiom to be self-evident; so when the scientists proved that the "earlier theological accounts of Nature" were wrong, and offered to replace them by mathematically exact and experimentally demonstrable "natural laws", it seemed equally self-evident that theirs was the way to true knowledge, of unchanging and unchangeable reality.

We may now formulate our second point:

During the Enlightenment, science replaced the classical philosophy and the Scripture in the role of our society's trusted way to true knowledge.

This allows us to comprehend the way in which we, academic people, perceive our role: We are (according to our self-perception) not the producers of practical knowledge, but the custodians the standard of true knowledge. And also the way in which this role is implemented:

We tend to take it for granted that the standard of true knowledge is constituted by the laboratories and departments of "basic science".

This is reflected both in academic ethos, and in the structure of the traditional European university—which favored "fundamental" fields such as mathematics, physics and philosophy; and relegated the more practical pursuits like architecture and design to "professional schools".

And now our third and last point, why the state of the art of knowledge of knowledge demands that we change both our ethos and institutional structure:

The assumption that science is the way to the knowledge of unchanging and unchangeable reality has been challenged and disowned by science itself.

While we federated this fact carefully, to see it, it is sufficient to read Einstein. (In our condensed or high-level manner of speaking, Einstein has the role of the icon of "modern science". Quoting Einstein is our way to say "here is what modern science has been telling us".)

It is simply impossible, Einstein remarked (while writing about "Evolution of Physics" with Leopold Infeld), to open up the 'mechanism of nature' and verify that our ideas and models correspond to the real thing. We cannot even conceive of such a comparison! Science is only an "attempt to make the chaotic diversity of our sense-experience correspond to a logically uniform system of thought".

In a moment we shall propose an altogether different approach to founding truth and meaning—completely independent of "reality" or "correspondence theory". Instead of calcifying the foundations as what science is, we'll show how to make it a function of what science knows! We'll introduce an art and science of constructing foundations for cultural artifacts, so that our culture may grow large and strong.

We shall point to a way to allow the foundations of truth and meaning to evolve continuously—so that our culture may evolve in sync with academic and other insights.

But before we do that, let us illustrate the depth and the breadth of the epistemological gulf that now separates our popular understanding of "language, truth and reality" (to borrow Whorf's timely title, already 80 years old), and what we actually know about those matters. A vast and profoundly creative foundations frontier is opening up. Let us visit it, however briefly, to see how profoundly our handling of everyday matters is likely to change, when we make the overdue fundamental changes.

We condense a spectrum of academic insights to a handful of engaging stories or vignettes; and we combine vignettes into threads—where they enhance one another, and sometimes produce an overall dramatic effect.

The Piaget–Lakoff–Oppenheimer thread illustrates how profoundly the 20th century scientific results challenge the naive idea of right knowledge that marked the academia's ascent. The Odin–Bourdieu–Damasio thread shows that we need to understand the relationship between information and power in a completely new way.

We shall see who, or what, keeps 'Galilei in house arrest' today today—without any need for censorship or prison.

As a cognitive psychologist studying "the construction of reality in the child", Jean Piaget observed that children develop their conception of reality by manipulating physical objects. By studying "the metaphors we live by" as a cognitive linguist, George Lakoff concluded that abstract thinking is largely metaphorical—that it uses our experiences with physical objects as templates. By exploring why quantum physics is so difficult to comprehend, Robert Oppenheimer concluded (in "Uncommon Sense") that the small quanta of matter-energy defy common sense by behaving in ways that are different from anything we have in experience.

Scientific truth is not and cannot be confined to what "makes sense". Richard Feynman observed (in "The Character of Physical Law"):

"It is necessary for the very existence of science that minds exist which do not allow that nature must satisfy some preconceived conditions."

But this turns Plato's conception of true knowledge on its head, doesn't it?

Even more dramatic are the changes in our understanding of power and freedom—which the available insights now demand.

In "Social Construction of Reality", Berger and Luckmann described the social process by which "reality" is constructed. They pointed to the role that a certain kind of reality construction called "universal theories" (theories about the nature of reality, which determine how truth and meaning are to be created) play in maintaining a given social and political order of things. The Biblical worldview of Galilei's prosecutors—which invested the monarch with some of Almighty's absolute power— is a familiar historical example.

The Odin–Bourdieu–Damasio thread reveals something essential about ourselves, which we must know to be able to able to untangle the cultural knot we are in and "change course".

This thread offers the data we need to be able to resolve a mystery: How we could be loving our children "above all else"—and still continue destroying the living substrate of our planet, and committing them to a dystopian future? And also Why we could have been Alexander's mercenaries and Hitler's soldiers, or "cogs that mesh perfectly" of a modern corporation.

The Odin–Bourdieu–Damasio thread allows us to understand the inner, social-psychological workings of the power structure.

Since we already offered an outline of this thread, we here only highlight the 'dots' that need to be connected.

Through the turf behavior of horses as metaphor, Odin the Horse vignette points to an instinctive drive that we humans also share—to dominate and control; and to expand our 'turf', whatever it may be. Even if we may not want to take part in the human 'turf strife', we still live in the ecology that is created by it, and suffer the consequences.

The second vignette allows us to perceive culture, and the societal order of things we are socialized to accept as reality, as symbolic 'turf'.

As an alert witness of Algeria's war for independence, Pierre Bourdieu saw how power morphed in modernity—from the "classical" instruments such as censorship and prison, to the "symbolic" ones, woven in modern economy and culture.

And to understand the process, which we call socialization, by which that 'turf', and the "reality picture" that holds it together, are created.

Bourdieu's "theory of practice" explains how power play can be rampant without anyone's awareness.

Bourdieu used two keywords—"field" and "game"—to refer to the symbolic or cultural 'turf'. By calling it a field, he suggested something akin to a magnetic field, which orients our seemingly random or free behavior, without us noticing. By calling it a game, he portrayed it as something that structures or 'gamifies' our social existence, by giving each of us a certain set of 'action capabilities', in accordance with our role. "The boss" has a certain body language and tone of voice; and so does "his secretary". Bourdieu used the keyword "habitus" to point to 'action capabilities'. The "habitus", according to Bourdieu, tends to be transmitted from body to body directly. Everyone kneels down when the king enters the room; so naturally we do too.

Bourdieu's repeated emphasis that a "habitus" is "both structured and structuring" needs to be carefully considered. His point was that the human turf is completely unlike the leveled meadow of the horses; it is indeed as more sophisticated as our culture is compared to the culture of the horses.

The human 'turf' is a structured result of historical 'turf strifes'.

Bourdieu keyword "doxa" points to the role that our "reality picture" plays in turning us into willing participants in this often so profoundly unjust and so infamously destructive 'game'. (This keyword has a rich and interesting history in social studies, which through Max Weber reaches at least as far back as Aristotle.) "Doxa" is a specific and widely common experience—that our social order of things is as immutable and as real as the physical reality we live in. "Orthodoxy" admits that other possible "reality pictures" exists, but claims that only a single one is the "right" one. "Doxa" ignores even the possibility of alternatives.

The third vignette, whose lead protagonist is the cognitive neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, allows us to understand why "doxa", or socialized reality, has such an uncanny cognitive grip on us humans.

As a cognitive neuroscientist, Damasio explained the anatomy and the physiology of the doxic experience. Damasio's is a simple result with profound consequences: When a certain nerve that connects the brain with the body is severed, the patient preserves the capability to reason rationally—and loses the capability to perceive relevance and set priorities. Damasio concluded that while the brain does the thinking, the body determines what we are capable of thinking.

In a book titled "Descartes' Error", Damasio explained why the "homo sapiens" self-image that the modernity gave us is profoundly misleading: We are not only, and not even primarily the rational decision makers, as we tend to believe. Our rational decision making, and our consciously maintained reality picture in general, are largely controlled by an embodied cognitive filter, which determines what options we are able to rationally consider.

Damasio explained how we may be living in two "realities", and have two disparate sets of values—the ones we uphold rationally; and the socialized or embodied ones.

To honor this new self-conception, we adapted Johan Huizinga's the keyword, to point to our alternative identity, as homo ludens.

Damasio's research allows us to understand why we civilized humans don't rationally consider taking off our clothes and walking out in the street naked; and why we don't consider changing the systems in which we live and work either.

This reverses the common idea of power.

We may now condense the above cognitive and epistemological insights to a single point.

The relationship we have with information is a result of a historical error.

This error has been detected and reported, but not corrected.

Its practical consequences include:

- Stringent limits to creativity. A vast global army of selected, trained and publicly sponsored creative men and women are obliged to confine their work to only observing the world—by looking at it through the lenses of traditional disciplines.

- Severed tie between information and action. The perceived purpose of information being to complete the 'reality puzzle'—every new "piece of information" appears to be just as relevant as any other; and also necessary for completing the 'puzzle'. Enormous amounts of information are produced "disconnected from usefulness"—as Postman diagnosed.

- Reification of institutions. Our "science", "democracy", "public informing" and other institutions have no explicitly stated purposes, against which their implementations may be evaluated; they simply are their implementations. It is for this reason that we use 'candles as headlights'.

- Destruction of culture. To see it, join us on an imaginary visit to a cathedral: There is awe-inspiring architecture; Michelangelo's Pietà meets the eye, and his frescos are near by. Allegri's Miserere is reaching us from above. And then there is the ritual. This, and a lot more, comprises the human-made 'ecosystem' called "culture", where the "human quality" grows. The myths of old, including the myth that "truth" means "correspondence with reality", were mere means by which the cultural traditions pursued this all-important end. We discarded this 'ecosystem' because we discredited its "reality picture". But "reality" is not—and it has never been—what the culture is about. The 'cultural species' are rapidly going extinct. In culture we don't have 'the temperature and the CO2 measurements', to be able to diagnose problems and propose policies.

- Culture abandoned to power structure. It is sufficient to to look around: Advertising is everywhere. And explicit advertising is only a tip of an iceberg. Variuos kinds of "symbolic power" are being used to socialize us as unaware consumers or willing voters—as the story of Edward Bernays (Freud's American nephew who became "the pioneer of modern public relations and propaganda") might show.

The following conclusion suggests itself:

The Enlightenment did not liberate us from power-related reality construction.

Our socialization only changed hands—from the kings and the clergy, to the corporations and the media.

Remedy

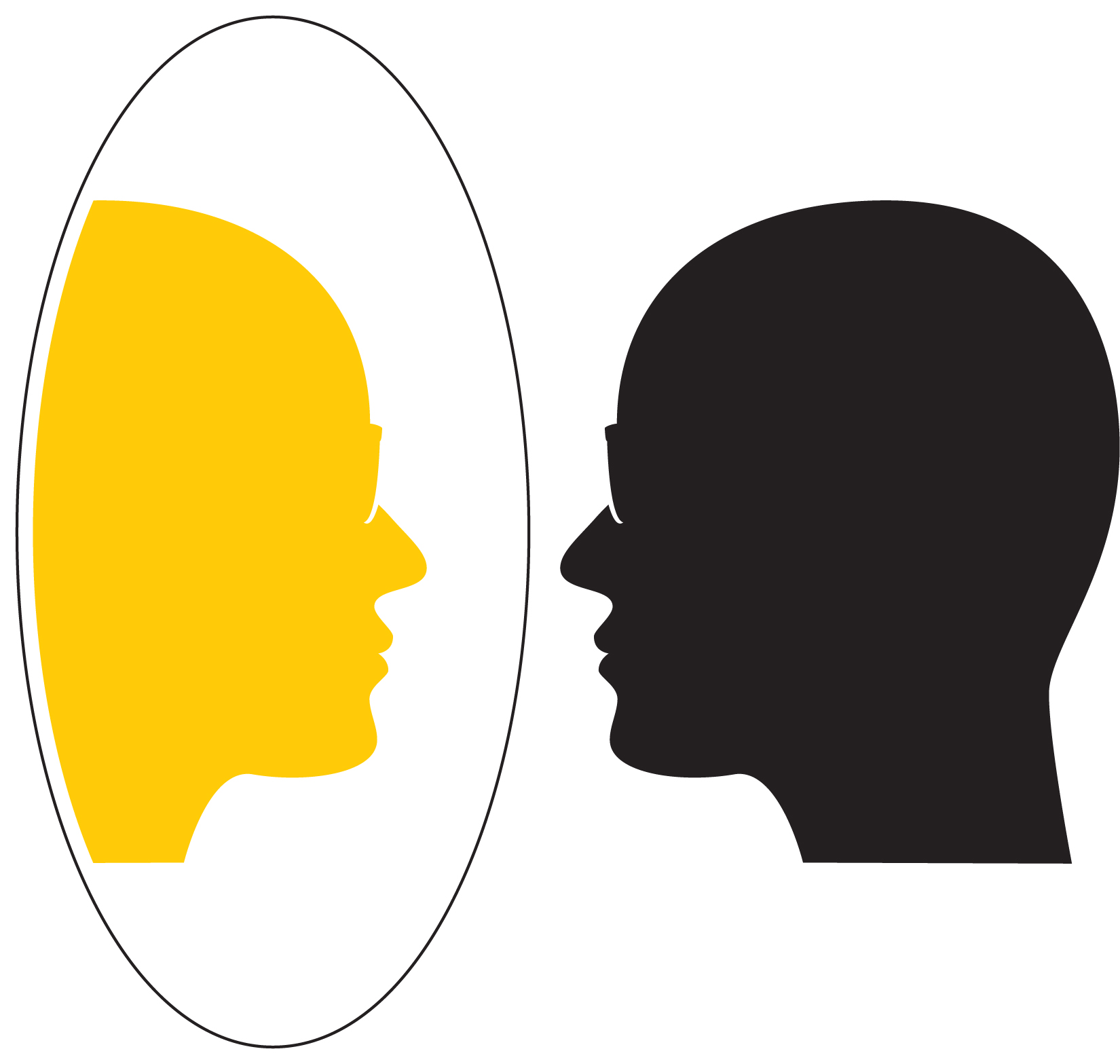

The Mirror ideogram characterizes our contemporary academic situation, and points to the way in which that situation needs to be handled.

Twenty-five centuries of evolution of the academic tradition have brought us here, in front of the mirror. The mirror demands that we restore the original academic ethos—by engaging in self-reflective, Socratic dialog.

As the case was then, the purpose of this dialog is to rid ourselves of socialized and inflated "knowing". But instead of using only common sense and philosophical reasoning—this contemporary dialog will be informed by the epistemological insights of the 20th century science and philosophy.

As we have just seen, a dialog of this kind is likely to change our self-perception and our self-identity quite thoroughly.

When we see ourselves in the mirror, we see ourselves in the world.

The mirror symbolizes self-awareness. It symbolizes putting ourselves into the picture. When we see ourselves in it, we realize that we are not disembodied spirits, looking at the world "objectively".

The world we see ourselves in, when we look at the mirror, is a world in dire need—for creative insights and acts of new, unprecedented kinds. We see ourselves in a pivotal, vitally important role in that world. Unavoidably, we begin to consider ourselves accountable for that role.

The mirror symbolizes the abolition of reification, and the restoration of accountability.

But the main message of this metaphor is to point to an unexpected, or even incredible or 'magical' way out of our contemporary entanglement.

We can step right through the mirror!

And into an entirely different way to look at the world; which empowers us to see, and create, an entirely different world.