Holotopia

Holotopia

Imagine...

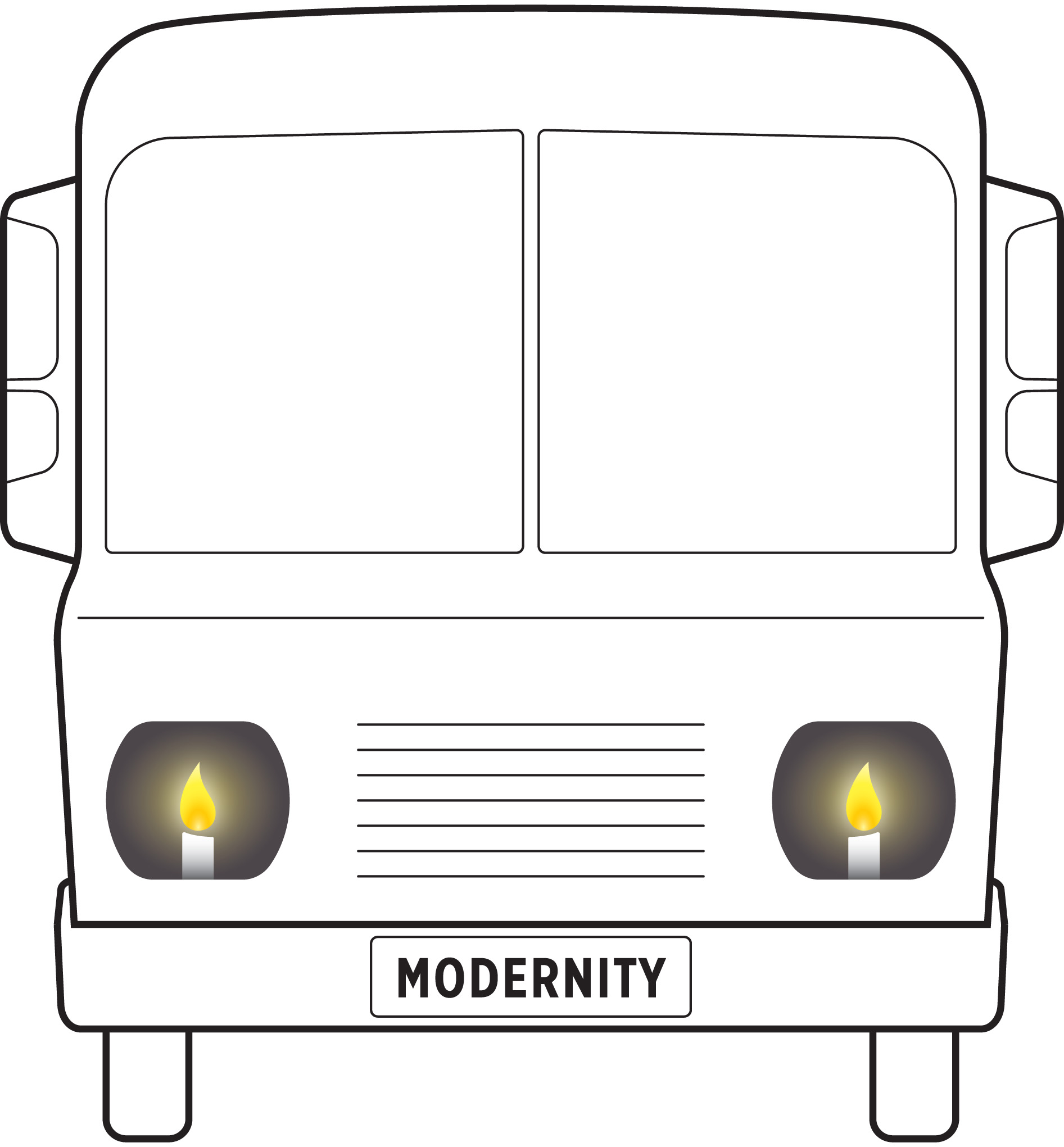

You are about to board a bus for a long night ride, when you notice the flickering streaks of light emanating from two wax candles, placed where the headlights of the bus are expected to be. Candles? As headlights?

Of course, the idea of candles as headlights is absurd. So why propose it?

Because on a much larger scale this absurdity has become reality.

The Modernity ideogram renders the essence of our contemporary situation by depicting our society as an accelerating bus without a steering wheel, and the way we look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it as guided by a pair of candle headlights.

Scope

The question we'll explore here is the one posed by the Modernity ideogram: How do we need to "look at the world, try to comprehend and handle it".

We build part of our case for the holoscope and the holotopia by developing an analogy between the last "great cultural revival", where a fundamental change of the way we look at the world (from traditional/Biblical, to rational/scientific) effortlessly caused nearly everything to change. Notice that to meet that sort of a change, we do not need to convince the political and business leaders, we do not need to occupy Wall Street. It is the prerogative of our, academic occupation to uphold and update and give to our society this most powertful agent of change—the standard of "right" knowledge.

Diagnosis

So how should we look at the world, try to comprehend it and handle it?

Nobody knows!

Of course, countess books and articles have been written that could inform an answer to this most timely question. But no consensus has emerged—or even a consensus about a method by which that could be achieved.

That being the case, we'll begin this diagnostic process by simply sharing what we've been told while we were growing up. Which is roughly as follows.

As members of the homo sapiens species, we have the evolutionary privilege to be able to understand the world, and to make rational choices based on such understanding. Give us a correct model of the natural world, and we'll know exactly how to go about satisfying "our needs", which we of course know because we can experience them directly. But the traditions got it all wrong! Being unable to understand how the nature works, they put a "ghost in the machine", and made us pray to the ghost to give us what we needed. Science corrected this error. It removed the "ghost", and told us how 'the machine' really works.

Of course no rational person would ever write this sort of a silly idea. But—and this is a key point in this diagnosis—this idea was not written. It has simply emerged—around the middle of the 19th century, when Adam and Moses as cultural heroes were replaced for so many of us by Darwin and Newton. Science originated, and shaped its disciplinary divisions and procedures before that time, while still the tradition and the Church had the prerogative of telling people how to see the world, and what values to uphold.

From a collection of reasons why this popular idea of what constitutes the "scientific worldview" needs to be updated, we here mention only two.

The first reason is that the nature is not a mechanism.

The mechanistic or "classical" worldview of 19th century's science was disproved and disowned by modern science. Even the physical reality cannot be understood as a mechanism, or explained in "classical" or "causal" terms. Werner Heisenberg, one of the progenitors of this research, expected that the largest impact of modern physics would be on popular culture—because the way of looking at the world that it took over from the 19th century's science, which he called the "narrow frame" (and which we adapted as a keyword), would be removed.

In "Physics and Philosophy" Heisenberg described how the destruction of religious and other traditions on which the continuation of culture and "human quality" depended, and the dominance of "instrumental" thinking and values (which Bauman called "adiaphorisation") followed from the assumptions that the modern physics proved were wrong.

In 2005, Hans-Peter Dürr, Heisenberg's intellectual "heir", co-authored the Potsdam Manifesto, whose title and message was "We have to learn to think in a new way". The new way of thinking, conspicuously impregnated by "seeing things whole" and seeing ourselves as part of a larger whole, was shown to follow from the worldview of new physics, and the environmental and larger social crisis.

The second reason is that even mechanisms, when they are complex, cannot be understood in causal terms.

This insight is the main one we needed to acquire from the systems sciences, and from cybernetics in particular.

It has been said that the road to Hell is paved with good intentions. There is a scientific reason for that: The "hell" (which you may imagine as the global issues, or as the destination toward which our 'bus' is currently taking us) consisting largely of "side effects" of our best efforts, and "solutions". <p> Hear Mary Catherine Bateson (cultural anthropologist and cybernetician, and the daughter of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson who pioneered both fields) say:

"The problem with Cybernetics is that it is not an academic discipline that belongs in a department. It is an attempt to correct an erroneous way of looking at the world, and at knowledge in general. (...) Universities do not have departments of epistemological therapy!"